Gerard de Lairesse

Gerard or Gérard (de) Lairesse (11 September 1641 – June 1711) was a Dutch Golden Age painter and art theorist. His broad range of skills included music, poetry, and theatre. De Lairesse was influenced by the Perugian Cesare Ripa[1][2] and French classicist painters such as Charles le Brun, Simon Vouet and authors such as Pierre Corneille and Jean Racine. His importance grew in the period following the death of Rembrandt.[3] His treatises on painting and drawing, Grondlegginge Ter Teekenkonst (1701),[4][5][6] based on geometry and Groot Schilderboek (1707), were highly influential on 18th-century painters.[7]

Painting career

De Lairesse was born in Liège and was the second son of painter Renier de Lairesse (1597-1667). He studied art under his father and from 1655 under Bertholet Flemalle.[8] He worked in Cologne and Aix-la-Chapelle for Maximilian Henry of Bavaria from 1660. In 1664 De Lairesse fled from Liège after an affair with two sisters, his models, led to difficulties. He travelled north with a girl named Marie Salme and married her in Visé. The couple settled in Utrecht, where a son was baptized in April 1665. When his talent as an artist was discovered by the art dealer Gerrit van Uylenburgh, he moved to Amsterdam. De Lairesse arrived with his violin, with which he impressed Jan van Pee and probably Anthonie Claesz de Grebber in Uylenburgh's studio.[9] In 1670 a son, Abraham, was born; the engraver Abraham Blooteling, with whom he collaborated, was the witness at the baptism;[10] another son was baptized in 1673.[11]

In 1671, when Van Uylenburgh tried to sell 13 paintings to Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, Hendrick Fromantiou successfully advised the Elector to send 12 pieces back as forgeries. Fromantiou claimed the paintings were copies of Italian ones, and he could point out the originals in Holland. De Lairesse was one of 51 individuals involved because of their expertise.

Some time later De Lairesse moved to Spinhuissteeg where he became a member of the literary society Nil volentibus arduum, which seems to have gathered in his house from 1676 until 1681.[12] In 1682 he sold copies of sheet music composed by Lully.[13] In May 1684 he rented the nearby house of Caspar Barlaeus.[14] His pupils Philip Tideman and Louis Abry lived there too.

De Lairesse produced paintings as decorations for the Soestdijk Palace between 1676 and 1683. In 1684 he moved to the Hague and worked there for a year. In 1685 he painted works for the Loo Palace. In 1688–1689, he decorated the civil council chamber of the Hof van Holland at the Binnenhof, presently known as the Lairesse room, with seven paintings with subjects from the history of the Roman Republic, all displaying a remarkable legal iconography.[15]

Style

At first, De Lairesse was highly influenced by Rembrandt, but later he focused on a more French-oriented style similar to Nicolas Poussin.[16] The French even nicknamed him the "Dutch Poussin", although he was also influenced by Pierre Mignard and Charles Alphonse du Fresnoy.

In Amsterdam during the second half of the 17th century, the pious austerity of the Protestant Dutch in Rembrandt's age had given way to unbridled opulence, even decadence, and de Lairesse's classical French, or Baroque, style fitted this age perfectly. It made him one of, if not the most popular painter in Amsterdam at that time. De Lairesse was therefore frequently hired to adorn the interiors of government buildings and homes (canal houses) of wealthy Amsterdam businessmen with lavish grisailles, trompe-l'œil ceilings and wall paintings. Some of these paintings still exist in the original buildings where they were painted.

De Lairesse as art theorist

De Lairesse was born with congenital syphilis, which caused him to go blind around 1690.[17] The saddle nose which the disease gave him is clearly visible on the portrait which Rembrandt painted of him around 1665 and the engraving in the "Teutsche Academie" by Joachim von Sandrart (1683).[18] After losing his sight, De Lairesse was forced to give up painting and focused instead on lecturing twice a week. De Lairesse explicitly states that despite his blindness, he was still able to design a perfect composition. He drew on two chalk boards and was assisted by his audience and his son Johannes who collected their notes. After several years two books on art were published:

- Grondlegginge ter teekenkonst ("Foundations of Drawing"), published in 1701[4][5]

- Het groot schilderboeck ("Great Book of Painting"), published in 1710

In Het groot schilderboeck, De Lairesse expressed his disapproval of realism style used by Dutch Golden Age painters like Rembrandt, Adriaen Brouwer, Adriaen van Ostade and Frans Hals because they often portrayed everyday scenes and ordinary people such as soldiers, farmers, maids, and even beggars. In De Lairesse's view, paintings ought to show lofty biblical, mythological and historical scenes, in the spirit of Karel van Mander, who felt that a complex historical allegory was the highest of genres. "A good painting has a clue, indicating what holds the composition together."[2]

De Lairesse distinguishes two manners of painting, good and bad, that both take their starting point in the imitation of reality. The right choice is to look for beauty and grace and to select the most perfect manifestations of natural phenomena, instead of copying them at random. This method will produce art that exerts a strong effect on the mind of the spectator. It is based on knowledge, understanding, power of judgement, and natural gifts.[2]

He was a disciplined intellectual, inspired by the notion that only correct theory could produce good art. For him theory meant the strict adherence to rules. The ultimate purpose of the visual arts was the improvement of mankind, and therefore art must, above all, be lofty and edifying. He set forth hierarchies of social status, of subject matter, of beauty itself. The artist, he said, must learn grace by mingling with the social and intellectual élite, must allow his subject matter to teach the highest moral principles, and must strive for ideal beauty. He must follow closely upon nature but overlook its imperfections.[19]

In the main reception room there should be tapestries or paintings on the wall with life size figures ... and in the kitchen, images of kitchen equipment and the spoils of the hunt, the picture of some maid, servant, dog or cat. De Lairesse, for whom pictorial illusionism was of utmost importance, also wrote about the place of pictures on walls. For example, he urged that landscapes (and indeed all paintings) should be hung at a height where their horizons were even with eye level. De Lairesse urged that portraits that be hung high and have a low viewpoint. Gerard de Lairesse was cognizant of the problems posed by viewing paintings from a distance and drew connection between the hanging position and the scale and style of individual paintings. He noted ... that a piece ten feet large, with life-size figures, should be viewed at ten feet distance, and that a smaller one five feet high, with life-size, half-length figures, must have five feet distance.[20]

Legacy

His treatises on painting and drawing, Grondlegginge ter teekenkonst (1701)[4][5][6] and Het groot schilderboeck (1707), were highly influential on later painters like Jacob de Wit. He also worked with many established artists of his day, as Barend Graat, Johannes Glauber and Frederick de Moucheron, on larger commissions for house decorations.

De Lairesse attracted many pupils, including Jan van Mieris, Simon van der Does, and the brothers Teodor and Krzysztof Lubieniecki. According to Houbraken, Jan Hoogsaat was one of his best pupils.[21] According to the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD), his pupils also included Jacob van der Does (the Younger), Gilliam van der Gouwen, Louis Fabritius Dubourg, Theodor Lubienitzki, Bonaventura van Overbeek, Jan Wandelaar.[22]

Celebrated during his lifetime and well into the 18th century, he was berated during the 19th century. With or without justification, he was considered superficial and effete, and was held in large part responsible for the decline in Dutch painting. Two hundred years after his death in 1711 the Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th Edition (1911) gave no listing at all for De Lairesse, while devoting four pages of solid text to Rembrandt.[19]

Works by De Lairesse are now on display at many museums around the world, including the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdams Historisch Museum in Amsterdam, the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Gallery in London, and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In 2016–2017, an exhibition and conference dedicated to De Lairesse's work was held at Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede.[23]

Works

Well-known paintings by de Lairesse include his Allegory of the Five Senses (1668), Diana and Endymion (c. 1680) and Cleopatra Landing at Tarsus. Some of his paintings show influence by the Iconologia of Cesare Ripa, a book that was given to him by his brother, after returning from Italy.[24] A versatile artist, De Lairesse also made many prints for book illustrations (e.g. for the poet Andries Pels) (1668). Among other things, De Lairesse produced:

- A set of illustrations for Gerard Reynst's collection Signorum Veterum Icones (1670), a series of prints based on the Italian statuary in Reynst's Amsterdam collection.

- Three ceiling paintings Triomf der Vrede (Triumph of Peace) in 1671 for the Amsterdam regent Andries de Graeff. The paintings glorified the De Graeff family's role as the protector of the Dutch republic and the works of art can be viewed as a visual statement opposing the return of the House of Orange as Stadtholders of the republic. They were created for Andries de Graeffs 'Sael' at his mayor's residence in Amsterdam. The ceiling paintings now adorn the Ferdinand Bol room at the Peace Palace in The Hague.[25][26]

- Most of his plates were originally published by Nicolaes Visscher II, who published a collected edition under the title 'Opus Elegantissimum' in c. 1675.[27]

- Set designs for the Schouwburg of Van Campen, the Amsterdam theatre (after 1676 or 1681 when it was reopened).[28]

- A set of illustrations for Govert Bidloo's anatomical atlas Anatomia Humani Corporis (1685). 105 illustrations in: Godefridi Bidloo, Medicinae Doctoris & Chirurgi, Anatomia Hvmani Corporis: Centum & quinque Tabvlis Per artificiosiss. G. De Lairesse ad vivum delineatis, Demonstrata, Veterum Recentiorumque Inventis explicata plurimisque, hactenus non-detectis, Illvstrata[29][30] Amsterdam 1685

- The shutters for the church organ in the Westerkerk in 1686.

- A portrait of the Dutch stadholder and king of England, William III of England (1688).

Title page of Signorum Veterum Icones, 1670

Title page of Signorum Veterum Icones, 1670 Anatomical drawing from Anatomia Humani Corporis, 1685

Anatomical drawing from Anatomia Humani Corporis, 1685 Ontleding des menschlyken lichaams

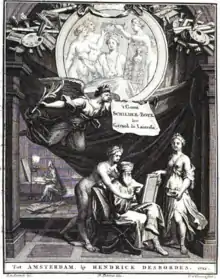

Ontleding des menschlyken lichaams Title page of Groot Schilderboek, 1712[31]

Title page of Groot Schilderboek, 1712[31]

References

- Gérard de Lairesse, Groot schilderboek, 1707

- Lyckle de Vries "De Lairesse on the theory and practice"

- Johnson, HA (24 May 2012). "Horton A Johnson, "Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (6): 301–303. doi:10.1177/014107680409700616. PMC 1079501. PMID 15173339.

- Lairesse, Gérard de, Grondlegginge ter teekenkonst 1701, full digital copy

- Lairesse, Gérard de, Grondlegginge ter teekenkonst 1701, full digital copy, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

- Grondlegginge der teekenkonst (1701) and Groot Schilderboek (1707)

- "Gerard de Lairesse" (in Dutch). Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

- Gerard de Laires biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- Lammertse, F. & J. van der Veen (2006) Uylenburgh & Zoon. Kunst en commercie van Rembrandt tot Lairesse, p. 217.

- Amsterdam City Archives

- Amsterdam City Archives

- "Triumpf of Peace". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- J.H. GISKES (1994) Amsterdam, centrum van muziek, muzikanten en schilders in de Gouden Eeuw, pp. 51–54. In: Jaarboek Amstelodamum.

- Maandblad Amstelodamum 1949, p. 59.

- T. Lubbers, 'Art for the Court: A new interpretation of Gerard de Lairesse's paintings for the Court of Appeal of Holland (1688-1689)', Oud Holland 2019/132, issue 2/3, pp. 109-134.

- The principles of drawing : or, an easy and familiar method whereby youth are directed in the practice of that useful art. Being a compleat drawing book: ... To which is prefix'd, an introduction to drawing; ... Translated from the French of Monsieur Gerard de Lairesse, and improved with abstracts from C. A. Du Fresnoy.'"

- Fifteenth- to Eighteenth-century European Paintings, p. 144. by Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Charles Sterling

- Vitenporträt Gérard de Lairesse (Academia 1683, Tafel 7)

- Johnson, HA (24 May 2012). "Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes". J R Soc Med. 97 (6): 301–3. doi:10.1177/014107680409700616. PMC 1079501. PMID 15173339.

- Loughman, J. & J.M. Montias (2000) Public and Private Spaces. Works of Art in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Houses, p. 34, 41, 106, 117-118.

- (in Dutch) Biography of Jan Hoogsaat in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- Gerard de Lairesse in the RKD

- "Gerard de Lairesse: Heden en Toekomst", Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age

- Letje Lips (2009) "Barend Graat Amsterdam 1628-1709"

- "Triumph of Peace (en)". Triomfdervrede.nl. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Restoration project Triumph of Peace completed

- British Museum

- Ben Albach (1977) Langs Kermissen en Hoven, p. 123.

- Bidloo, Govard (1685). Anatomia humani corporis, centum & quinque tabulis, per artificiossis. G. de Lairesse ad vivum delineatis, demonstrata, veterum recentiorumque inventis explicata plurimisque, hactenus non-detectis, illustrata. Amsterdam: Sumptibus viduæ J. a Someren – via University of Toronto Libraries.

- Bidloo, Govard; Lairesse, Gérard de [Ill.] (30 August 2012). Bidloo, Govard; Lairesse, Gérard de [Ill.]: Godefridi Bidloo, Medicinae Doctoris & Chirurgi, Anatomia Hvmani Corporis: Centum & quinque Tabvlis Per artificiosiss. G. De Lairesse ad vivum delineatis, Demonstrata, Veterum Recentiorumque Inventis explicata plurimisque, hactenus non detectis, Illvstrata (Amsterdam, 1685). Digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Groot schilderboek, waar in de schilderkonst in al haar deelen grondig werd onderweezen, ook door redeneeringen en printverbeeldingen verklaard; met voorbeelden uyt de beste konst-stukken der oude en nieuwe puyk-schilderen, bevestigd : en derzelver wel- en misstand aangeweezen, Volume 1, Gérard de Lairesse, Philip Tideman, Gilliam van der Gouwen, Jan van Broekhuizen, Jan Caspar Philips, David van Hoogstraten, Johannes Vollenhove, Abraham Alewyn, Matthijs Pool, published by Henri Desbordes, Amsterdam, 1712, Digital version of the work on Google Books

External links

![]() Media related to Gerard de Lairesse at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gerard de Lairesse at Wikimedia Commons

- Allegory on Science at the Rijksmuseum, a grisaille by de Lairesse

- Godefridi Bidloo, Medicinae Doctoris & Chirurgi, Anatomia Hvmani Corporis: Centum & quinque Tabvlis Per artificiosiss. G. De Lairesse ad vivum delineatis, Demonstrata, Veterum Recentiorumque Inventis explicata plurimisque, hactenus non detectis, Illvstrata 105 illustrations by Gérard de Lairesse. Amsterdam 1685

- Jan Joseph Marie Timmers (1942) "Gérard Lairesse", coll. "Academisch proefschrift Nijmegen, 1", Amsterdam.

- Track on YouTube with many of his paintings