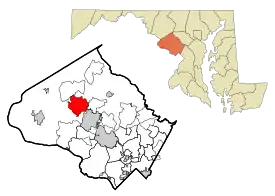

Germantown, Maryland

Germantown is an urbanized census-designated place in Montgomery County, Maryland. With a population of 91,249 as of the 2020 census, it is the third most populous place in Maryland, after Baltimore and Columbia.[2][3][4] Germantown is located approximately 28 miles (45 km) outside the U.S. capital of Washington, D.C., and is an important part of the Washington metropolitan area.

Germantown, Maryland | |

|---|---|

Germantown Library | |

| |

Germantown  Germantown | |

| Coordinates: 39°11′0″N 77°16′0″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maryland |

| County | Montgomery |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.12 sq mi (44.35 km2) |

| • Land | 17.03 sq mi (44.12 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.23 km2) |

| Elevation | 428 ft (130 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 91,249 |

| • Density | 5,357.19/sq mi (2,068.40/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 20874, 20875 (PO box only), 20876 |

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-32025 |

Germantown was founded in the early 19th century by European immigrants, though much of the area's development did not take place until the mid-20th century. The original plan for Germantown divided the area into a downtown and six town villages:[5] Gunners Lake Village, Kingsview Village,[6] Churchill Village, Middlebrook Village,[7] Clopper's Mill Village, and Neelsville Village.[8] The Churchill Town Sector at the corner of Maryland Route 118 and Middlebrook Road most closely resembles the center of Germantown because of the location of the Upcounty Regional Services Center, the Germantown Public Library, the Black Rock Arts Center, and pedestrian shopping that features an array of restaurants. Three exits to Interstate 270 [I-270] are less than one mile away, the Maryland Area Regional Commuter train is within walking distance, and the Germantown Transit Center that provides Ride On shuttle service to the Shady Grove station of the Washington Metro's Red Line.

Germantown has the assigned ZIP codes of 20874 and 20876 for delivery and 20875 for post office boxes. It is the only "Germantown, Maryland" recognized by the United States Postal Service, though three other Maryland counties have unincorporated communities with the same name.

History

Early history (1830–1865)

In the 1830s and 1840s, the central business area was focused around the intersection of Liberty Mill Road and Clopper Road. Several German immigrants set up shop at the intersection and the town became known as "German Town", even though most residents of the town were of English or Scottish descent.[9]

American Civil War

Although it avoided much of the physical destruction that ravaged other cities in the region, the Civil War was still a cause of resentment and division among residents of Germantown. Many Germantown residents were against slavery and had sons fighting for the Union Army. In contrast, other residents of Germantown owned slaves, and even those who were not slave-owners had sons fighting for the Confederate Army. As a result, many people in Germantown, who had been on friendly terms with each other, made an effort not to interact with each other, such as switching churches, or frequenting a store or mill miles away from the ones they would normally do business with.[10]

Late in the summer and fall of 1861, there were more than twenty thousand Union soldiers camped to the west of Germantown, in neighboring Darnestown and Poolesville. Occasionally, these soldiers would come to Germantown and frequent the stores there. In September 1862 and in June 1863, several regiments of Union Army soldiers marched north on Maryland Route 355, on their way to the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, respectively. In July 1864, General Jubal Early led his army of Confederate soldiers down Maryland Route 355 to attack the Union capital of Washington, D.C. Throughout the course of the war, Confederate raiders would often pass through the Germantown area. Local farmers in the Germantown area lost horses and other livestock to both Union and Confederate armies.[11]

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

In 1865, George Atzerodt, a co-conspirator in the assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, was captured in Germantown. Atzerodt had come to the town with his family from Prussia when he was about nine years old. About five years later, his father moved the family to Virginia, but Atzerodt still had many friends and relatives in Germantown.[12] He was living in Port Tobacco during the Civil War, and supplementing his meager income as a carriage painter by smuggling people across the Potomac River in a rowboat. This clandestine occupation brought him into contact with John Surratt and John Wilkes Booth and he was drawn into a plot to kidnap President Lincoln. On April 14, 1865, Booth gave Atzerodt a gun and told him that he was to kill U.S. Vice President Andrew Johnson, which he refused to do.[12] When he found out that Booth had shot Lincoln, Atzerodt panicked and fled to the Germantown farm of his cousin Hartman Richter, on Schaeffer Road near Clopper Road. He was discovered there by soldiers on April 20, six days after the assassination. Atzerodt was tried, convicted and hanged on July 7, 1865, along with co-conspirators Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, and David Herold at Washington, D.C.'s Fort McNair.[12][13][14]

Expansion (1865–1950)

Germantown did not have a public school until after the end of the American Civil War. During that time, education was handled at home. In 1868, a one-room schoolhouse was built on Maryland Route 118, near Black Rock Road, which hosted children from both Germantown and neighboring Darnestown.[15] In 1883, a larger one-room schoolhouse was built closer to Clopper Road. Another, newer school was constructed in 1910, on what is now the site of Germantown Elementary School.[15] This school had four rooms, with two downstairs and two upstairs, with each room housing two grade levels. After the eighth grade, the students would head via train to nearby Rockville, for further education.[15]

The wooden structure of the Bowman Brothers Mill fell victim to a fire in 1914. Four years later, the owners were back in business again, selling the mill to the Liberty Milling Company, a brand new corporation. Augustus Selby was the first owner and manager of the new Liberty Mill, which opened in 1918. Electricity was brought into Liberty Mill and also served the homes and businesses nearby, making Germantown the first area in the northern portion of Montgomery County to receive electricity.[16]

In 1935, professional baseball player Walter Perry Johnson, who played as a pitcher for the Washington Senators (now the Minnesota Twins), purchased a farm on what is now the site of Seneca Valley High School. Used as a dairy farm, Johnson lived there with his five children and his mother (his wife had died), until his death in 1946.[17] A road near the school was named after him.

"Feed the Liberty Way" was used as a slogan for Liberty Mill which, with eight silos, became the second largest mill in all of Maryland, supplying flour to the United States Army during World War II. Cornmeal and animal feed were also manufactured at Liberty Mill, and a store at the mill sold specialty mixes, such as pancake and muffin mix.[18] Following the end of World War II, the Liberty Mill went into disrepair. For over 25 years, the mill continued to deteriorate until it was destroyed by an arsonist on May 30, 1972.[19] The cement silos were removed by the county in 1986 to make way for the MARC Germantown train station commuter parking lot.[20]

Development and master plan (1950–1980)

%252C_by_Dan_Brodt.jpg.webp)

In January 1958, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission was relocated from its location in downtown Washington, D.C., to Germantown, which was considered far enough from the city to withstand a Soviet nuclear attack.[21] The facility now operates as an administration complex for the U.S. Department of Energy and headquarters for its Office of Biological and Environmental Research.[22]

Marshall Davis owned a farm located where I-270 and Germantown Road intersect today.[23] After I-270 divided his farm in two, Davis decided to sell the last of his land to the International Development Corporation for about $1,300 per acre in 1955.[23] Fairchild-Hiller Corporation bought the land for about $4,000 per acre in 1964, and it built an industrial park on the land four years later.[23] Harry Unglesee and his family sold their farm near Hoyles Mill Road for less than $1,000 per acre in 1959.[23] Other farmers soon sold their land to developers and speculators as well.[23]

The Germantown Master Plan was adopted in 1967.[24] The plan for the 17-square-mile (44 km2) area included a dense central downtown area and less dense development surrounding it.[7] In 1974, the Montgomery County Council approved an amended plan written by the Montgomery County Planning Board.[24] The amended plan included a downtown area and six separate villages, each comprising smaller neighborhoods with schools, shopping areas, and public facilities.[7] The amended plan also included the construction of a third campus for Montgomery College near the downtown area.[7] The same year, the completion of a sewer line helped the development and growth of Germantown.[25]

During the 1970s, Wernher von Braun, a German rocket scientist during World War II, worked for the aerospace company Fairchild Industries, which had offices in Germantown, as its vice president for Engineering and Development. Von Braun worked at Fairchild Industries from July 1, 1972, until his death on June 16, 1977.[26] The A-10 Thunderbolt and the landing gear of the Space Shuttle were both designed at these offices.[27]

The Germantown Campus of Montgomery College opened on October 21, 1978. At the time, it consisted of two buildings, 24 employees, and 1,200 students.[28] Enrollment had increased to five thousand students by 2003, with eighty employees across four buildings. A steel water tower modeled after the Earth can be seen from orbiting satellites in outer space. As of 2008, a forty-acre bio-technology laboratory was nearing completion.[29]

Economic growth and modern development (1980–present)

Since the early 1980s, Germantown has experienced rapid economic and population growth, both in the form of townhouses and single-family dwellings, and an urbanized "town center" has been built. Germantown was the fastest growing zip code in the Washington metropolitan area and Maryland in 1986, and the 1980s saw a population growth of 323.3% for Germantown.[30]

In 2000, the Upcounty Regional Services Center opened in Germantown, and a 16,000 square feet section of the first floor was home to the Germantown Public Library for several years until it moved to a new, 19 million dollar complex in 2007.[31][32][33] On September 29, 2013, it was renamed as the Sidney Kramer Upcounty Regional Services Center after Sidney Kramer, Montgomery County executive from 1986 to 1990.[31]

In October 2000, the Maryland SoccerPlex opened in Germantown.[34] The sports complex includes nineteen natural grass fields, three artificial fields, a 5,200 seat soccer stadium with lighting and press box, eight indoor convertible basketball/volleyball courts.[35] Two miniature golf courses, a splash park, a driving range, an archery course, community garden, model boat pond, two BMX courses, tennis center, and a swim center are also located within the confines of the complex.[35] The soccerplex was the home of the Washington Spirit of the National Women's Soccer League from 2013 to 2019.[34]

On October 14, 2002, the D.C. snipers briefly stopped at Milestone Shopping center in Germantown.[36]

In 2003, one of Germantown's trailer parks, the Cider Barrel Mobile Home Park, closed after decades of operation, having been in business since at least the 1970s.[37][38] Despite this closure, the Barrel building itself was preserved, with a cluster of garden apartments erected near it.[37]

On August 14, 2011, a 7-Eleven convenience store in downtown Germantown fell victim to a flash mob robbery of nearly forty people.[39] The incident garnered widespread attention in the United States and internationally.[39]

Holy Cross Health opened a 237,000-square-foot (22,000 m2) hospital on the campus of Montgomery College in October 2014, becoming the first hospital in the U.S. to be built on a community college campus.[40] The opening of the new 93-bed hospital strengthened the college's medical program by giving students the opportunity for hands-on work and access to more advanced medical technology.[40] The hospital was projected to eventually bring 5,000 new jobs to the area.[41]

In August 2017, Brandi Edinger initiated efforts to crowdfund the repurposing of the historic Cider Barrel as a bakery via Kickstarter, but failed to meet the $80,000 goal set.[42] On January 1, 2020, it was reported that plans are underway to reopen the Barrel in the spring of that year after it was closed for nearly two decades.[43] However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic it had been delayed indefinitely.[44]

Geography

Germantown is located approximately 428 feet above sea level, at 39°11′N 77°16′W.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the community has a total area of 10.9 sq mi (28.0 km2), of which all but 0.039 sq mi (0.1 km2) (0.46%) is land.

Climate

Germantown lies within the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen Cfa), with hot, humid summers, cool winters, and generous precipitation year-round.[45] Its location above the Fall Line in the Piedmont region gives it slightly lower temperatures than cities to the south and east such as Washington, D.C., and Silver Spring.[45] Summers are hot and humid with frequent afternoon thunderstorms. July is the warmest month, with an average temperature of 86 °F (30.0 °C).[46] Winters are cool but variable, with sporadic snowfall and lighter rain showers of longer duration. January is the coldest month, with an average temperature of 29 °F (−1.7 °C).[46] Average annual rainfall totals 40.36 in (103 cm).[45]

| Climate data for Germantown (2022) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 60.8 (16.0) |

71.6 (22.0) |

75.2 (24.0) |

86.0 (30.0) |

93.2 (34.0) |

93.6 (34.2) |

96.7 (35.9) |

97.0 (36.1) |

89.5 (31.9) |

76.9 (24.9) |

78.1 (25.6) |

62.6 (17.0) |

97.0 (36.1) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 36.9 (2.7) |

44.6 (7.0) |

53.6 (12.0) |

64.4 (18.0) |

73.4 (23.0) |

82.1 (27.8) |

87.8 (31.0) |

88.0 (31.1) |

80.7 (27.1) |

62.2 (16.8) |

57.3 (14.1) |

40.8 (4.9) |

64.3 (18.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 21.1 (−6.1) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

35.6 (2.0) |

41.0 (5.0) |

55.4 (13.0) |

62.5 (16.9) |

64.3 (17.9) |

66.2 (19.0) |

57.7 (14.3) |

44.8 (7.1) |

34.9 (1.6) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

44.2 (6.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8.6 (−13.0) |

10.4 (−12.0) |

15.8 (−9.0) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

35.5 (1.9) |

46.7 (8.2) |

59.0 (15.0) |

55.3 (12.9) |

42.9 (6.1) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

3.0 (−16.1) |

3.0 (−16.1) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.88 (73) |

2.81 (71) |

3.61 (92) |

3.22 (82) |

4.13 (105) |

3.49 (89) |

3.67 (93) |

2.90 (74) |

3.83 (97) |

3.29 (84) |

3.53 (90) |

3.00 (76) |

40.36 (1,026) |

| Source: [46] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 9,721 | — | |

| 1990 | 41,145 | 323.3% | |

| 2000 | 55,419 | 34.7% | |

| 2010 | 86,395 | 55.9% | |

| 2020 | 91,249 | 5.6% | |

| Source:[47] 2010–2020[2] | |||

As of 2013 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, Germantown had a population of 90,676.[48] As of the census of 2010, there were 86,395 people, and 30,531 households residing in the area.[49] The population density was 8,019 inhabitants per square mile (3,096/km2). The racial makeup of the area was 36.3% white, 21.8% African American, 0.2% Native American, 19.7% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.3% from other races, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 18.4% of the population.

There were 20,893 households, out of which 41.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.8% were married couples living together, 13.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.4% were non-families. 23.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 1.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.80 and the average family size was 3.19.

In the area, the population was spread out, with 28.9% under the age of 18, 7.7% from 18 to 24, 43.0% from 25 to 44, 17.3% from 45 to 64, and 3.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.6 males.

The median income for a household in Germantown was $76,061 as of a 2010 estimate by the website, City-Data.[50] 6.5% of the population and 3.5% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total people living in poverty, 5.9% are under the age of 18 and 9.9% are 65 or older.[50]

In 2023, WalletHub honored Germantown as the most ethnically diverse city in the United States.[51]

| Population by race in Germantown, Maryland (2010) | ||

| Race | Population | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 86,395 | 100 |

| Caucasian | 31,102 | 36.3 |

| African American | 18,813 | 21.8 |

| Asian | 17,001 | 19.7 |

| Hispanic | 15,879 | 18.4 |

| Other | 258 | 0.3 |

| Two or more races | 2,847 | 3.3 |

| American Indian | 172 | 0.2 |

| Source:[52] | ||

Economy

Since development began in the late 20th century, Germantown has experienced economies of agglomeration, with many high-tech companies opening headquarters and other offices in Germantown and other areas along the I-270 corridor. Qiagen North America, Earth Network Systems Inc., Digital Receiver Technology Inc.,[53] Mid-Atlantic Federal Credit Union, and Hughes Network Systems all have their headquarters in Germantown.[54]

In addition to the companies headquartered in Germantown, many have offices in the area, including Wabtec, Viasat, RADA USA, Mars Symbioscience, Xerox, General Electric Aviation, Earth Networks, WeatherBug, and Proxy Aviation Systems.[55]

Government

Despite its size, Germantown has never been incorporated formally as a town or a city. It has no mayor or city council and is thus governed by Montgomery County. It is now represented by Democrat Marilyn Balcombe in the Montgomery County Council, after being represented by Craig L. Rice from 2010 through 2022.[56] Germantown is part of two districts for the Maryland General Assembly, 15 (ZIP code 20874), and 39 (ZIP code 20876).[57] For the US Congress, it is part of Maryland's 6th district.[58]

The U.S. Department of Energy has its headquarters for the Office of Biological and Environmental Research in Germantown.[22] The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission was moved from its location in downtown Washington, D.C., to the present-day U.S. Department of Energy building in Germantown because of fears of a Soviet nuclear attack on the U.S. capital.[59] At the time, Germantown was believed to be far enough from Washington, D.C., to avoid the worst effects of a nuclear strike on the city.[59] The facility now operates as an administration complex for the U.S. Department of Energy.[60]

Education

All the public schools in Germantown are part of the Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) system.[61] The elementary schools in Germantown are Cedar Grove Elementary School, Clopper Mill Elementary School, Fox Chapel Elementary School, Germantown Elementary School, Great Seneca Creek Elementary School, Captain James E. Daly Jr. Elementary School, Lake Seneca Elementary School, Ronald McNair Elementary School, Sally K. Ride Elementary School, Spark Matsunaga Elementary School, S. Christa McAuliffe Elementary School, Waters Landing Elementary School, and William B. Gibbs, Jr. Elementary School.[61]

The four middle schools are Kingsview Middle School, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, Neelsville Middle School, and Roberto W. Clemente Middle School, which feed into three high schools: Northwest High School, Clarksburg High School and Seneca Valley High School. Students from Kingsview move on to Northwest, students from Neelsville move on to Clarksburg while those from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Roberto W. Clemente Middle Schools move on to Seneca Valley High School.[61] Additionally, the Longview School, which provides special education services, is located in Germantown.[62]

Montgomery College, the largest higher education institution in Montgomery County, has its largest campus in Germantown. It is located on Observation Drive not far from the downtown area.[28]

Culture

Music

The BlackRock Center for the Arts is located in the downtown Germantown, at the Germantown Town Center. The BlackRock Center for the Arts also sponsors the Germantown Oktoberfest, an annual festival held every year in the fall, which includes various genres of music, including traditional German folk, rock and pop.[63] The Harmony Express Men's Chorus is a 4-part a cappella men's chorus based in Germantown.[64]

The band Clutch is also from Germantown. Members of the group attended Seneca Valley High School together, with several members graduating with the Class of 1989. Two years later, in 1991, the band was formed.[65]

Sports

The Maryland SoccerPlex sports complex is located in Germantown. Maureen Hendrick's Field at Championship Stadium hosts many amateur, collegiate, and regional soccer and lacrosse tournaments.[34] The Montgomery County Road Runners Club annually hosts the Riley's Rumble Half Marathon & 8K that starts and finishes in the SoccerPlex.[66] The SoccerPlex formerly hosted the Washington Spirit of the National Women's Soccer League. The Germantown Swim Center is also located within the SoccerPlex. The swim center has hosted many major swimming events including Metros and the 2022 Landmark Conference Swimming & Diving Championship.[67]

Historical society

The Germantown Historical Society (GHS) was formed in 1990 as a non-profit organization with a mission to educate the public about local history and preserve local historic sites.[68] The GHS office and future museum is located in the historic Germantown Bank (1922) at 19330 Mateny Hill Road, across from the MARC railroad station. The GHS offers lectures on local history and has traveling exhibits about Germantown.[68] It also sells the books, Liberty Mill T-shirts, and other souvenirs. The main fundraiser for the organization is the Germantown Community Flea Market, held on the first Saturday of the month April through November in the MARC parking lot, Rt. 118 and Bowman Mill Drive, featuring more than 150 vendors.[68]

Media

Germantown is served by a news and information website known as the Germantown Pulse.[69] The Germantown Pulse covers a wide range of topics, including sports, schools, crime, music, and other events of note in the area.[69] However, its main website ceased to update by August 2019.[70]

Veterans

Germantown veterans are served by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, American Legion Post 295.[71] American Legion Post 295 sponsors Cub Scout Pack 436, a Venturing Crew and is establishing a Sea Scout Ship. American Legion Boys State and American Legion Baseball have been longtime programs supported by the Post.[71]

Transportation

%252C_Germantown%252C_Maryland%252C_September_9%252C_2013.jpg.webp)

Germantown is bisected by I-270, one of Maryland's busiest highways. Northbound traffic heads toward Frederick and I-270 and southbound traffic heads toward Bethesda and the Capital Beltway.[72] I-270 has three exits in Germantown.[72]

Germantown also has a station on the MARC train's Brunswick Line, which operates over CSX's Metropolitan Subdivision. The station building itself, at the corner of Liberty Mill Road and Mateny Hill Road, is a copy of the original 1891 structure designed by E. Francis Baldwin for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[73] The modern station building was rebuilt after it was destroyed by arson in 1978.[74]

The Montgomery County public transit bus system, Ride On, serving Montgomery County with over 100 bus routes, operates a major transit hub in Germantown known as the Germantown Transit Center.[75] The transit center serves approximately 20 routes, making it one of the largest transit centers in the county.[75]

As of 2017, a light rail system, the Corridor Cities Transitway, is under evaluation. If constructed, the system would connect the terminal of the Washington Metro Red Line, Shady Grove station in nearby Derwood to Germantown and continue northward to Clarksburg.[76]

In popular culture

Germantown is featured in the video game Fallout 3 (2008). After the town has been destroyed by a nuclear war, 'Germantown Police HQ' subsequently becomes a mutant-run prison camp.[77] While the in-game location name 'Germantown Police HQ' is actually a misnomer. The location is most likely based on the single real-life police station in the town, which is a County Police Station. Sam Fisher, the protagonist of the Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell video game series, lives on a farm in rural Germantown, according to the novelizations of the series.[78][79]

Germantown is featured in several episodes of the U.S. television series The X-Files, notably as a hotbed for biomedical engineering and research, as in reality.[80] There are indeed a handful of biomedical research facilities in the area. The show's creator, Chris Carter, stated that he decided to set several episodes in Germantown as his brother used to live in the town.[81] In one or more episodes, Germantown is depicted as being near a wharf or harbor; this is not accurate to the actual area.

Notable people

- Members of rock band Clutch, attended and formed the band at Seneca Valley High School[65]

- Danny Heater, a high school basketball player and single game scoring record holder lived in Germantown[82]

- Members of rock band, Hootie and the Blowfish, attended Seneca Valley High School[83]

- Walter Perry Johnson, a professional baseball pitcher for the Washington Senators, lived on a dairy farm in Germantown (where Seneca Valley High School currently stands) with his mother and children, from 1935 to his death in 1946[17]

- Mia Khalifa, a Lebanese pornographic actress and adult model, attended Northwest High School[84][85]

- Shahzeb "ShahZaM " Khan, former professional Counter-Strike: Global Offensive player and current Valorant player for G2 Esports, attended Roberto W. Clemente Middle School

- Bobby Liebling of doom metal band Pentagram

- Jake Rozhansky (born 1996), American-Israeli professional soccer player[86]

- Frank Warren, the founder of PostSecret[87]

- Isaiah Swann (born 1985), professional basketball player

- Harvey D. Williams, African-American U.S. Army major general; lived in Germantown until his death in 2020[88]

- Edward William VI, former professional Street Fighter III: Third Strike Dudley player. [89]

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- "QuickFacts: Germantown CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- "Maryland Trend Report 2: State and Complete Places". Missouri Census Data Center. Missouri State Library, Missouri Secretary of State. March 8, 2011. Archived from the original on February 28, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- Burke, Garance (July 17, 2003). "Germantown Looking to Incorporate: Area Would Be County's Largest Municipality". The Washington Post. p. T03.

- Perez-Rivas, Manuel (October 6, 1996). "A Community In Progress; Fast-Growing Germantown Stands Apart in Montgomery". The Washington Post. p. A01. ProQuest 307939077.

- Meyer, Eugene L. (December 26, 1987). "Antigrowth Battle Forges Germantown Identity". The Washington Post. p. B1. ProQuest 306957084.

- Bonner, Alice (January 9, 1974). "Revision Approved Of Germantown Plan: 'New Town' Plan Change Is Approved". The Washington Post. p. C1. ProQuest 146220112.

- "Neelsville Village Center". Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

The crossroads became known as "German town" because of the heavy German accents of these people. The name has stuck even though a majority of the land-owners in the area were of English or Scottish descent.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

The Civil War took a terrible toll on Germantown, not because there was any actual fighting here, but because of the animosities between neighbors that it created. Many of the families of German descent were against slavery and had sons fighting in the Union army. Many of the families of English descent owned slaves and even many who didn't, had sons fighting in the Confederate army. Many people who had formerly been friendly went out of their way to not have to deal with each other, some changing churches, or going to a mill or store miles distant from the one they usually used.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

In the late summer and fall of 1861 there were more than 20,000 Union soldiers camped to the west of Germantown in the Darnestown and Poolesville areas. Sometimes these soldiers would come to the stores in Germantown. In September, 1862, and June, 1863, many regiments of Union soldiers marched north on Rt. 355 on their way to the Battles of Antietam and Gettysburg. In July, 1864, Gen. Jubal Early led his Confederate army down Rt. 355 to attack Washington, D.C. Confederate raiders also came through the area several times during the War. Local farmers lost horses and other livestock to the armies of both sides.

- Kauffman, M. (2004). American Brutus. Random House. pp. 282–284. ISBN 0-375-75974-3.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society.

- "George Atzerodt: The Reluctant Assassin," The Montgomery County Story, Montgomery County Historical Society, Vol. 58 No. 1, summer 2015

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

There was no public school in Germantown until after the Civil War. Before that time school was held in people's homes. In 1868 there was a one-room school on built on Rt. 118 near Blackrock Road that served the children of both Germantown and Darnestown. In 1883 a larger one-room school was built closer to Clopper Road to teach the children of Germantown. Another new school was built in 1910 on the present site of Germantown Elementary school. This school had four rooms—two downstairs and two upstairs—each room housing two grades. After eighth grade the children rode the train to attend high-school in Rockville.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

Fire engulfed the old wooden structure of the Bowman Brothers Mill in 1914, but four years later they were in business again and sold the mill to a brand new corporation—the Liberty Milling Company. Augustus Selby was the first owner/manager of the new mill which opened in 1918. Electricity was brought into the mill and also served the homes and businesses nearby, making this the first area in the northern part of the county to get electricity.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

Johnson bought his dream farm in Germantown in 1935 and lived here with his five children and his mother, his wife having passed away, until his death in 1946. His dairy farm was located where Seneca Valley High School is today. He was elected by the local people to two terms as a County Commissioner.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

"Feed the Liberty Way" was the slogan for the mill which, with its 8 silos, became the second largest mill in Maryland and supplied flour for the army during World War II. Cornmeal and animal feed were also made at the mill, and a mill store sold specialty mixes like pancake and muffin mix.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

After the war the mill went into decline, and was burned by arson in 1971.

- "The Dawn of the Industrial Age in Germantown". August 25, 2011.

- "Redirection Page". U.S. DOE Office of Science (SC). Archived from the original on September 11, 2009.

- "U.S. Office of Biological and Environmental Research". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- Barringer, Felicity (September 19, 1977). "Once-Rural Germantown Growing Up". The Washington Post. p. A1. ProQuest 146738794.

- "Germantown Master Plan Boasts a Time Schedule". The Washington Post. August 11, 1973. p. E21. ProQuest 148394807.

- Germantown Historical Society. "Germantown's History, A Brief Overview". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

The area felt a new surge of energy with the building of interstate 270 in the 1960s. For a while the old and the new mixed as employees of the Atomic Energy Commission (now the Department of Energy) came to the old Germantown store for lunch and Mr. Burdette's cows often had to be cleared from the road. When the sewer line was completed in 1974 building in Germantown began in earnest.

- "Wernher von Braun Biography". A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- "Fairchild Apartments in Germantown recall the golden age of Montgomery County (Photos)".

- "Montgomery College – Germantown Campus". Montgomery College. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- Coleman, Margaret (2008). Then & Now: Around Germantown. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7385-5416-7. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

Montgomery College, Germantown Campus, opened October 21, 1978, with two buildings, 1,200 students, and a faculty of 24. A steel water towel modeled Planet Earth as seen from a satellite. By 2003, enrollment was 5,000 with 80 faculty members in four buildings. A 40-acre biotechnology laboratory is nearing competition in 2008.

- Meyer, Eugene L. (March 17, 1987). "Germantown: Zip Code Seeking Identity; Montgomery Community's Dream Is Sidetracked by Economics". The Washington Post. p. A1. ProQuest 306866256.

- Carignan, Sylvia (September 30, 2013). "Germantown center renamed for former county executive: Ceremony to be held Sept. 29". The Gazette. 9030 Comprint Court, Gaithersburg, Maryland: Post-Newsweek Media, Inc. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Coleman, Margaret (2008). Then & Now: Around Germantown. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7385-5416-7. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

Until recent years, Germantown book lovers went to the library in Gaithersburg or patronized the weekly bookmobile. In the year 2000, the Upcounty Regional Services Center opened and the largest first-floor space became the library. In 2007, the Germantown Public Library moved to its own, separate location. The new library opened at a cost of $19 million. Now library space is enlarged from 16,000 to 44,193 square feet on two levels. There are 180,000 volumes on the shelves, and 37 PCs available for public use.

- "Germantown Community Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County, Maryland. November 1996. Archived from the original on March 30, 1997.

- "Maryland Soccerplex History". Maryland Soccer Foundation. May 6, 2000. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Maryland Soccerplex Map". Maryland Soccer Foundation. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t7sSzi4c_Fc&list=PLOYjsh73gPKRoMOpdsZwLm_ny3cNyoSgy&index=21&ab_channel=FOX5WashingtonDC

- Tierney, Meghan (November 28, 2007). "County's last trailer park to close". The Gazette. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "William E. Cross Foundation Awards $20,000 to Support Montgomery College Students". Montgomery College. December 3, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

The Cross family established the Cider Barrel Mobile Home Park on Route 355 in Germantown, Md., not far from the College's Germantown Campus.

- Justin Jouvenal and Dan Morse (August 15, 2011). "Police probe Germantown flash-mob thefts". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- "About Holy Cross Health – Germantown". Holy Cross Health. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- "Holy Cross Germantown Hospital". Holy Cross Health. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- Zimmermann, Joe (August 10, 2017). "Germantown Resident Hopes to Resurrect Cider Barrel as Bakery". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- Tsironis, Alex (January 1, 2020). "The Cider Barrel to Reopen This Spring". The MoCoShow. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- Pekow, Charles (April 6, 2022). "Will the Cider Barrel ever reopen?". Montgomery Magazine. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- "Germantown, Maryland, monthly averages". Intellicast. The Weather Channel, LLC. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Monthly Averages for Germantown, MD (20874)". Weather.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- "CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING (1790–2000)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- "Preference for Racial or Ethnic Terminology". Infoplease. Retrieved February 8, 2006.

- "2010 Census for Germantown, Maryland". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- "Germantown, Maryland". City-Data.

- Estulin, Shayna (February 22, 2023). "Germantown tops list of most diverse places in the US". WTOP. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- "Germantown, Maryland Population Statistics". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- DRT, Inc,

- "Contact Us Archived September 4, 2012, at archive.today." Library Systems & Services. Retrieved on September 27, 2010. "US Corporate Headquarters Library Systems & Services, LLC 12850 Middlebrook Road Suite 400 Germantown, MD 20874-5244."

- "Proxy Aviation Systems".

- Barros, Aline (February 19, 2015). "Germantown Named Second-most Diverse City in the Country". MyMCMedia. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

Germantown is not an incorporated city but is administered by the Montgomery County government.

- "Find My Representatives". Maryland General Assembly. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- "My Congressional District". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- "AEC History" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. July 1, 1983. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Germantown Site History". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "MCPS Clusters". Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Longview School". Montgomery County Public Schools.

- "Germantown Oktoberfest". Germantown, MD. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Harmony Express Men's Chorus". Harmony Society. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Clutch Biography". Pro Rock. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Riley's Rumble Half Marathon & 8K 2020 – CANCELLED". Montgomery County Road Runners Club. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- "2021–22 Landmark Conference Swimming & Diving Championship".

- "Germantown Historical Society". Germantown Historical Society. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- "Germantown Pulse". Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- O'Rourke, Kevin. "Thank You, Germantown, for Five Amazing Years". Germantown Pulse. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- "American Legion Post 295 Vietnam Veterans Memorial". American Legion Post 295. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- "Interstate 270 in Maryland". Interstate-Guide. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- "MARC Station Information – Brunswick Line". MARC. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- "Germantown Train Station History". Patch. January 23, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- "Ride On Bus". Montgomery County Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- "Corridor Cities Transitway Project Page". Maryland Transit Administration. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- "Fallout 3 Locations". Planet Fallout Wiki. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- Michaels, David (November 6, 2007). Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell: Fallout. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-101-00375-6.

- Michaels, David (November 7, 2006). Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell: Checkmate. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-101-00374-9.

- "Germantown". X-Files Roadrunners.

- Pegoraro, Rob (December 15, 1995). "GENERATION X". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- "Danny Heater". West Virginia Humanities Council. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- "Hootie and the Blowfish Biographies". All Music. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- Dan Steinberg (July 13, 2016). "A former porn star has become one of D.C.'s loudest sports fans on social media". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "Ex-Adult Star Mia Kalifa's Wild Educational Qualifications". MensXP. slide 6. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- "Jake Rozhansky – Virginia Bio". VirginiaSports.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "PostSecret Website". PostSecret. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Never to be forgotten" (PDF). The Triangle Tribune. Durham, North Carolina. February 28, 2016. p. 6A. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1983/04/17/magazine/behind-the-scene-with-ed-williams.html

External links

- Hybrid satellite image/street map of Germantown, from WikiMapia

- Germantown at the Wayback Machine (archived August 1, 2003)

- Germantown at the Wayback Machine (archived April 13, 1997)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)