Gila Wilderness

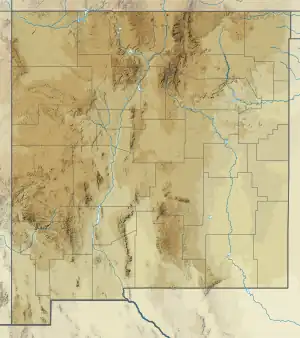

Gila Wilderness was designated the world's first wilderness area on June 3, 1924.[1] Along with Aldo Leopold Wilderness and Blue Range Wilderness, the 558,014 acre (225,820 ha) (872 sq. mi.) wilderness is part of New Mexico's Gila National Forest. The wilderness is approximately 27 miles (43 km) from north to south and 39 miles (63 km) east to west.[2]

| Gila Wilderness | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Catron/Grant counties, New Mexico, United States |

| Nearest city | Silver City, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 33°14′25″N 108°16′51″W |

| Area | 558,014 acres (225,820 ha) |

| Established | 1924 |

| Governing body | United States Forest Service |

U.S. Wilderness Areas do not allow motorized or mechanized vehicles, including bicycles. Camping, hunting, and fishing are allowed with proper permit, but no roads, buildings, logging, or mining are permitted. Wilderness areas within National Forests and Bureau of Land Management areas allow hunting in season.

The Gila Wilderness is located in southwest New Mexico, north of Silver City and east of Reserve. It contains the West Fork, Middle Fork and much of the East Fork of the Gila River; riverside elevations of around 4,850 feet (1,480 m) are the lowest in the wilderness. The Mogollon Mountains traverse an arc across the wilderness. The tallest peak within this range, Whitewater Baldy at 10,895 ft (3,321 m), is in the northwest part of the wilderness along with several other summits more than 10,000 ft (3,048 m) high. At the northeast corner is prominent Black Mountain rising to 9,287 ft (2,831 m).[3] The Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is adjacent to the wilderness.[4]

The Gila Wilderness is the largest designated wilderness area in New Mexico.

History

The Mimbres people, a subgroup of the Mogollon were active between 1000 and 1130 in the Gila Wilderness area, leaving cliff dwellings, ruins and other evidence of their culture. The Chiricahua band of Apache came into the area between 1200 and 1600.[2] Because of their fierce protectiveness, the area remained undeveloped into the 1870s.[5] In 1922, Aldo Leopold, a United States Forest Service supervisor of the Carson National Forest proposed that the headwaters area of the Gila River should be preserved by an administrative process of excluding roads and denying use permits. Through his efforts, this area became recognized in 1924 as the first wilderness area in the National Forest System.[6] Gila became the first congressionally designated wilderness[2] of the National Wilderness Preservation System when the Wilderness Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.

Flora and fauna

Vegetation in the Gila Wilderness consists of a spruce-fir and quaking aspen forest above 9,000 feet (2,732 m), ponderosa pine forest between 6,500 feet (1,981) and 9,000 (2,732 m), and pinyon-juniper woodland and desert vegetation below 6,500 feet and on dry southern slopes. Brushy areas, grassland, and recently burned forests are also common.[7] Within this generalized outline, a variety of Arizona Mountains forest ecosystems are found in the wilderness, mostly characteristic of a transition zone between the Chihuahuan Desert and flora typical of the Rocky Mountains. The wilderness includes mesquite, Apache pine and is the northernmost home of the Chihuahua pine.[8] Gila contains one of the world's largest and healthiest ponderosa pine forests.[9] Arizona sycamore, walnut, maple, ash, cottonwood, alder and willow trees are found along rivers and in canyons.[2]

Gila is home of predators such as the bobcat and cougar. Mule deer, white-tailed deer and pronghorn are all found in the wilderness. Other mammals include the black bear, collared peccary, gray fox and white-nosed coati. The critically endangered Mexican wolf was reintroduced to the wilderness in 1988 with eleven captive-raised individuals. Most died or were killed and more were released the following year.[10] As of 2006, four packs have established themselves within Gila.[11] Because of conflicts with livestock owners, the federal predator control program has killed or removed several animals.[12]

Bighorn sheep were common throughout the region until about 1900 when they became locally extinct through hunting. Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep were reintroduced to the Gila Wilderness after 1958 from a growing herd of Canadian releases in the Sandia Mountains.[13] Elk were reintroduced by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish in 1954 with sixteen animals from Yellowstone National Park.[14]

Game birds include wild turkey and dusky grouse; birds of prey include common black hawk, zone-tailed hawk, goshawk, osprey and bald eagle; American dippers are found in mountain streams.[8] The wilderness is home to the largest population of near threatened spotted owls, which prefer Douglas-fir or white fir stands and can be found in ponderosa pine forests with a well-developed Gambel oak understory.[15]

Reptiles such as the Arizona coral snake and Gila monster are rarely present;[16] common snakes include the black-tailed rattlesnake, rock rattlesnake, and Sonora mountain kingsnake. Brown trout, rainbow trout, catfish and bass are found in rivers and streams.[2] The threatened Gila trout is present in Iron, McKenna and Spruce Creeks. It prefers sufficiently deep water, such as American beaver ponds, which provide hiding places and can withstand both floods and drought.[17]

Four packs of Mexican wolves roam the wilderness.

Four packs of Mexican wolves roam the wilderness. The threatened Gila trout is found in the wilderness.

The threatened Gila trout is found in the wilderness. A beaver dam spans a section of the Middle Fork of the Gila River.

A beaver dam spans a section of the Middle Fork of the Gila River.

Recreation

The U.S. Forest Service describes the climate of the Wilderness area as "four gentle seasons."[18] The lower elevations below 7,000 feet (2,100 m) are accessible all year with heavy winter snow uncommon. Elevation moderates the high summer temperatures of the surrounding Chihuahua Desert. May and June are the hottest and dryest months. Many trails are relatively easy, following stream valleys bordered by cliffs or crossing flat-topped mesas. Water is often scarce due to frequent droughts. Summer temperatures can near 100 degrees F (37C), and the size and isolation of the wilderness increases the hazards of visiting. A hiker was found alive in 2007 after being lost 40 days in the Gila Wilderness, setting a new state record for the number of days for a lost person to be found alive. It is common for hikers to become lost in the vast expanse of the Gila; some are never found.[19]

The Gila Wilderness provides opportunities for fishing, hunting, backpacking, horseback riding and camping. It has hundreds of miles of hiking and horseback trails starting at over fifty easily accessible trailheads.[2] A visitor center near the Gila cliff dwellings is about two hours north of Silver City, New Mexico on State Route 15. Near here, at an elevation of 5,689 feet (1,734 m), trails radiate up the Middle Fork of the Gila River (41 miles [68 km] long) and the West Fork (34.5 miles [55 km] long) and downstream following the Gila River for 32.5 miles (51 km).[20] One of the best-known trails in the Wilderness is the "Catwalk," a one-mile trail suspended above a rushing stream in a gorge only a few feet wide. The Crest Trail, 12 miles long, passes through impressive sub-alpine forests in the highest portions of the Gila Mountains with elevations from 9,132 feet (2,783 m) to 10,770 feet (3,280 m).[21]

Many hot springs are found within the wilderness. Cliff dwellings border stream valleys, especially along the Middle Fork of the Gila River. Rafting the Gila River is popular in the spring when water levels in the river are high due to snowmelt in the higher mountains. Because it is a wilderness, visitors must minimize their impact on the natural environment by observing the Leave No Trace principles.

An alternate to the official Continental Divide Trail (CDT) follows the canyon of the Gila River through the wilderness and has been voted one of the favorite sections of the CDT.[22]

The Gila Wilderness is separated from the sizable Aldo Leopold Wilderness by only a gravel road and a few scattered pieces of private property. Aldo Leopold offers additional long-distance hiking and backpacking opportunities.

References

- Gila Wilderness at wilderness.net.

- Wilderness up close Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine at the National Park Service

- "Gila National Forest map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-24. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument at the National Park Service.

- Gila Cliff Dwellings at the National Park Service.

- Aldo Leopold at the US Forest Service.

- Cunningham, Bill and Burke, Polly. Hiking New Mexico's Aldo Leopold Wilderness. Helena, MT: A Falcon Guide, 2002, p. 4

- Gila Wilderness at New Mexico Wilderness Alliance.

- "Arizona Mountains forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Guided tours to help gray wolf’s come-back Archived 2007-06-11 at the Wayback Machine at Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- "Mexican Wolf Monthly Report: December 2006". Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- Federal Government Kills Another Endangered Mexican Gray Wolf. Center for Biological Diversity.

- Bighorn rooted in state's history.

- Interstate Swaps and Purchases Aid Game Restoration Program at U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Mexican Spotted Owl Recovery Program Archived 2008-05-23 at the Wayback Machine at U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- National Park Service: Gila Cliff Dwellings: Reptiles.

- Gila Trout at Center for Biological Diversity.

- "Gila National Forest." http://www.fs.usda.gov/generalinfo/gila/recretation/generalinfo/?groupid=4081&recid=1958, accessed 18 Apr 2012

- Hiker sets state record while enduring cold, snow at Las Cruces Sun-News.

- Murray, John A. The Gila Wilderness. Albuquerque: U of NM Press, 1988, pp. 113-125

- Murray, pp 77-81

- "The Continental Divide Trail Thru-Hiker Survey (2019)". Halfway Anywhere. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

External links

![]() Media related to Gila Wilderness at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gila Wilderness at Wikimedia Commons