Giovanni Colonna (historian)

Fra Giovanni Colonna (1298? – 1343/44) was an Italian Dominican friar and scholar. Educated in France, he served as a preacher and vicar in Rome, chaplain in Cyprus and lector in Tivoli. He lived and worked in Avignon for a time and traveled widely in the Near East during his Cypriot period.

An early humanist, he was a friend and correspondent of Petrarch, whose eight surviving letters to him are an important source for his later years, during which he suffered from gout. He wrote two works of history, Liber de viris illustribus ('Book of Famous Men') and Mare historiarum ('Sea of Histories'), the first during his time in Avignon and the second during his final years in Tivoli.

Life

Giovanni Colonna[1] was born in the 1290s, in 1298 according to some scholars.[2] He belonged to the family of the lords of Gallicano, a branch of the Colonna. His father, Bartolomeo di Giovanni, bore the title domicello di Belvedere.[3] He was a nephew of Landolfo Colonna. His great-great-great-grandfather was Oddone, the brother of Cardinal Giovanni Colonna.[4]

Beginning in 1315, Colonna was educated in France at Chartres, Troyes and Amiens.[5] During his stay in Chartres, he stayed with his uncle Landolfo.[6] He joined the Dominican Order before 1320, in which year he took up studying at the University of Paris. According to Petrarch, he was learned in philosophy. In 1324, the chapter of the Dominican province of Rome named him preacher-general. He was soon appointed chaplain to Giovanni Conti, archbishop of Nicosia, and moved to Cyprus until after Conti's death in 1332.[5] During this period, he visited the Holy Land.[6] In a letter to Colonna, Petrarch refers to his addressee's travels in Persia, Arabia and Egypt, which must have taken place during his service with Giovanni Conti.[7] Petrarch and Colonna maintained a correspondence during the years 1336–1343.[8]

From Cyprus, Colonna returned to Rome, whence he was sent to papal Avignon. It was there that he drafted his Liber de viris illustribus. Petrarch records that enemies in Avignon eventually forced him to return to Rome. He had to wait one month in Nice for a ship, which was then forced to return to port during a storm. When he finally landed in Pisa, he was seriously ill.[5]

In 1338, he was appointed vicar of the Dominican priory in Santa Sabina until a new prior was elected. In the fall of 1339, he was appointed lector of the priory at Tivoli. He passed the last years of his life there studying the classics and finishing his Mare historiarum.[5] In the days after his laureation on 8 April 1341, Petrarch joined Colonna in Rome and the two of them toured the city, visiting classical and early Christian monuments and discussing ethics, aesthetics and history.[9] Colonna suffered in his last years from gout. From Petrarch's letters it is clear that he was prematurely old, and Petrarch recommended reading Cicero's De senectute and Tusculanae disputationes.[10] The two met for the last time at Palestrina in October 1343. As indicated by a letter of Petrarch to Archbishop Guido Sette, Colonna died not long afterwards, towards the end of 1343 or early in 1344.[5] In all, eight of Petrarch's Epistolae familiares (family letters) are addressed to Colonna. His lost play Philologia was also dedicated to him.[11]

Works

Petrarch wrote of Colonna that he owned many books, was an expert in antiquities and wrote excellent Latin. A reading of his works reveals a critical mind equally comfortable in classical pagan texts and medieval Christian ones.[5] Roberto Weiss puts him in the early generation of humanist scholars at the papal court in Avignon. Of Colonna he writes that he "searched for ancient texts, studied them critically, and used them as sources in [his] writings."[12]

Liber de viris illustribus

Colonna's earlier work, Liber de viris illustribus ('Book of Famous Men'), was begun during his stay in Avignon. It consists of some 330 biographies and bibliographies of illustrious pagans and Christians. The book beings with a long philosophical introduction, followed by the pagan biographies arranged alphabetically and then the Christian biographies arranged in the same way. Colonna's model was Jerome's De viris illustribus. He also used the same-titled works by Gennadius and Isidore. Other important sources include Seneca, Lactantius, Eusebius, Pseudo-Walter Burley and the Speculum historiale of Vincent of Beauvais. Beyond a few extracts, De viris has never been edited or published.[5] Manuscripts from which certain extracts have been printed include:[5]

- Bologna, Biblioteca universitaria, MS lat. 491[5]

- Venice, Biblioteca Marciana, MS lat. X, 3173[5]

- Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, MS XX. VI.34 2396[5]

- Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Barb. lat. 2351[13]

Mare historiarum

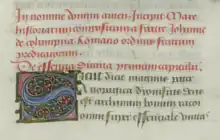

Colonna's later work, Mare historiarum ('Sea of Histories'), is a universal history from the creation of the world to 1250. Although he intended to bring it down to his own time, it was unfinished at his death. It relies heavily on Vincent's Speculum historiale. Other important sources for ancient history include Livy, Josephus, Lactantius and Jerome.[14] It survives in the following manuscripts:[15]

- Florence, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, MS Aedil. 173, the autograph[16]

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 4912[16]

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 4914[16]

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 4915, the only illustrated copy, with 730 miniatures[17]

- Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. lat. 4963[16]

- Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MSS Vat. Ott. 1541, 1542, 1543[18]

Notes

- Johannes de Columna in Latin: Modonutti 2016.

- 1298 is accepted by Modonutti 2016 and the Treccani editors, but questioned by Surdich 1982.

- Surdich 1982. For a family tree, see Balzani 1885, p. 235.

- Balzani 1885, p. 235.

- Surdich 1982.

- Modonutti 2016.

- The Giovanni Colonna who corresponded with Petrarch is sometimes identified with a brother of Sciarra Colonna, but it is most likely the Dominican. See Surdich 1982 and Wilkins 1963.

- Treccani editors.

- For the date, see Wilkins 1963. Surdich 1982 dates this tour to 1337. Petrarch in one letter names nearly 100 places they visited in Rome.

- Surdich 1982; Forte 1950, p. 390.

- Modonutti 2016 lists the letters as II, 5–8; III, 13; VI, 2–4. For an analysis of VI, 2, see Wilkins 1963. It was written in response to a request from Colonna that Petrarch put into writing his account of the origin of arts that he gave when the two were resting at the Baths of Diocletian.

- Weiss 1947, p. 21.

- Surdich 1982. Available online.

- Van Duzer 2012, pp. 282–283.

- Van Duzer 2012, p. 283 n.24, says "seven manuscripts", but lists only six.

- Van Duzer 2012, p. 283 n.24.

- Van Duzer 2012, p. 283.

- According to Forte 1950, p. 398, these are three separate manuscripts of books III, VI and VII copied on paper in the 17th century.

Bibliography

- Balzani, Ugo (1885). Landolfo e Giovanni Colonna secondo un codice Bodleiano. Reale Società romana di Storia patria.

- "Colónna, Giovanni". Enciclopedia on line. Treccani. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Forte, Stephen L. (1950). "John Colonna, O.P.: Life and Writings (1298–c. 1340)". Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum. 20: 369–414.

- Modonutti, Rino (2016). "Colonna, Giovanni". In Graeme Dunphy; Cristian Bratu (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Brill Online. doi:10.1163/2213-2139_emc_SIM_00746. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Ross, W. Braxton (1970). "Giovanni Colonna, Historian at Avignon". Speculum. 45 (4): 533–563. doi:10.2307/2855668. JSTOR 2855668. S2CID 163147750.

- Ross, W. Braxton (1985). "New Autographs of Fra Giovanni Colonna". Studi Petrarcheschi. n.s. 2: 211–229.

- Ross, W. Braxton (1989). "The Tradition of Livy in Mare historiarum of Fra Giovanni Colonna". Studi Petrarcheschi. n.s. 6: 70–86.

- Surdich, Francesco (1982). "Colonna, Giovanni". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 27: Collenuccio–Confortini (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Van Duzer, Chet (2012). "A Neglected Type of Medieval Mappamundi and Its Re-imaging in the Mare Historiarum (Bibliothèque nationale de France MS Lat. 4915, Fol. 26v)". Viator. 43 (2): 277–301. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.1.102714.

- Weiss, Roberto (1947). The Dawn of Humanism in Italy: An Inaugural Lecture. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilkins, Ernest H. (1963). "On Petrarch's Ep. Fam. VI 2". Speculum. 38 (4): 620–622. doi:10.2307/2851659. JSTOR 2851659. S2CID 163699232.