Giovanni Miani

Giovanni Miani (Rovigo 17 March 1810 – Tangasi 21 November 1872) was an Italian explorer. He is known for his explorations of the Nile, where he came close to being the first European to reach its source in Lake Victoria, and for his exploration of the region around the Uele River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Giovanni Miani | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 March 1810 Rovigo, Veneto, Italy |

| Died | 21 November 1872 (aged 62) Tangasi, near Niangara, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Explorer |

Early years (1810–1849)

Giovanni Miani was born on 17 March 1810 in Rovigo, Veneto, Italy. His mother was Maddalena Miani, a servant, sister of the architect Giovanni Miani of the Venice Arsenal and aunt of Antonio Miani, commander of the first Italian conquest of Fezzan in 1813. His father is unknown.[1] While he was a child his mother obtained service with the noble P. A. Bragadin, leaving Miani with some relatives, where he tried to learn the art of wood carving. He was reunited with his mother in 1824, and from then on Bragadin ensured that he had a "princely education" in music, letters, languages, dance, science, martial arts and drawing. Bragadin died on 8 August 1828 and Miani inherited his house and 18,000 Italian lire in a will that the other heirs contested.[1]

Miani's mother died in 1837, and Miani devoted himself to music, which he studied in conservatories in Bologna, Milan, Naples, Paris and Spain. In 1841 the Austrian police included Miani in their list of people under surveillance for his political views and acquaintances. Between 1841 and 1843 he wrote the words and music for Un torneo a Tolemaide, a melodrama that was published in Venice in 1843. In 1844 he published the first issue of Storia universale della musica di tutte le nazioni (General history of the music of all nations). He spent the next twenty years travelling in search of musical instruments and traditions for use in this project, exhausting his fortune in the process.[1]

Miani fought for Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian wars of the Risorgimento of 1848–1849.[2] He moved to Rome at the start of the revolution in 1848, then to the papal division of the Venetian Republic under General Andrea Ferrari (1770–1849), where he became sergeant major in the land artillery and participated in the defense of Marghera and the fort of San Secondo. In April 1849 he was accused of having defended the fort too weakly and of having conspired against General Amilcare Paulucci (1773–1845).[1] He was forced to leave Italy.[2]

Wanderings (1849–1859)

Miani moved to Constantinople, where he resumed composing. He visited Palestine and then spent a year in Cairo where he worked as tutor to the Lucovich family and then as director of some experimental rice plantations while studying archeology and philology.[1] According to Roberto Battaglia (1958) he was "the first Risorgimento patriot who chose Africa as his land of exile."[3] Miani returned to Italy and managed to raise 40,000 francs to continue publishing editions of the Storia universale della musica, and visited Paris and London in an unsuccessful attempt to find a publisher for this work.[1]

Once more in Egypt, Miani learned Arabic and became interested in exploring the interior of Africa.[2] He made several journeys in lower Egypt.[4] In 1857 he visited Upper Nubia with two young Frenchmen, and drew a map of the region based on his own observations and the accounts of sailors, merchants, hunters and missionaries. He had the map printed in Paris in 1858 and presented a copy to Napoleon III, along with his project for exploring the Nile basin to find the river's source. He was admitted to the Société de Géographie of Paris.[1]

First Nile expedition (1859–1860)

Miani was supported by the Eyptian government and the Société de Géographie in his 1859–1860 attempt to locate the source of the Nile. Napoleon III provided arms and ammunition.[5] Returning to Egypt on 10 May 1859 Miani left Cairo on two boats accompanied by a navy captain in charge of astronomical research, a photographer, a painter and an Arabic-French translator. The expedition reached Omdurman, the port of Khartoum, on 20 July 1859. There Miani met the Maltese merchant Andrea Debono. He made an excursion to Sennar on a government boat between 20 September 1859 and 7 November 1859 with a company that included his wife and son, Debono and four soldiers.[1]

Miani left Khartoum heading south on 5 December 1859.[1] He travelled with Debono's company, of which Samuel Baker wrote, "de Bono's people are the worst of the lot, having utterly destroyed the country."[2] The expedition passed the Santa Croce station of Catholic missionaries in the swamps of the Sudd and reached Gondokoro on 24 January 1860, which had been abandoned by Austrian missionaries. Miani made an attempt to pass the Makedo falls, then returned to Gondokoro in poor health to recuperate for two months. He then left by land with a company of 100 men, marching at some distance from the right bank of the river for about 200 kilometres (120 mi).[1]

In one incident related by Miani the soldiers tried to trade a woman they had captured to the chief of a Madi village in exchange for ivory, and also asked for a bag of grain. The chief refused and told them to leave. A fight broke out and the king was killed, his hands cut off to remove his bracelets, and his dismembered and castrated body paraded on the soldiers' weapons. Many villagers fled and others were burned alive after Miani ordered the village to be burned down. The soldiers took musical instruments and clothing for Miani's collection.[2]

Miani reached Galuffi on 26 March 1860, and engraved his name on a large tamarind tree.[1][lower-alpha 1] He talked to the local people there, but they did not tell him that the river came from the great lake nearby, and tried to persuade him not to continue.[6] In poor health, Miani continued south on 29 March 1860, and reached a latitude of 3°32'N, the closest any European had yet come to the source of the Nile.[1] He was sure it was another month's walk away, when in fact it was only 60 miles (97 km).[1] The local people were hostile, physical conditions were difficult, his escort refused to go further and he had to turn back.[4]

Miani reached Khartoum on 22 May 1860.[1] He made two more trips to hunt elephants and use the profits from sale of ivory to fund his exploration.[4] In July and August he travelled by boat on the Nile and then by camels and dromedaries to Suakin on the Red Sea, where he met the explorer Carlo Piaggia. He then returned to Cairo.[1] He had not succeeded in finding the Nile's sources, but had travelled further up the river than any European before.[7]

Europe and Egypt (1860–1872)

Miani returned to Cairo on 24 August 1860, and was laid up for a month while a sore on his foot healed. He published an account of his journey which was sent to all the European geographical societies, and sent an extract with a sketch map to the Egyptian Foreign Minister, who responded by guaranteeing aid for further exploration in the form of scientific instruments, money and transport. On 2 December 1860 Miani left Cairo on a steamer bound for Esna, accompanied by an astronomer, an artist and an escort of 150 soldiers. They reached Aswan on 25 December 1860, and travelling partly by water, partly by land around the cataracts, reached Omdurman, where his expedition fell apart. He returned to Cairo, and on 6 October 1861 sailed for Europe.[1]

Miani spent several years in Europe participating in geographical debates.[2] He exhibited his collection in the Palazzo Pretorio in Florence, and in January 1862 published a short report of his travels in Turin. He went on to Paris and London, then to Venice in August 1862, where he received some compensation for his collection. On 27 October 1862 Miani proposed to the Venice Chamber of Commerce to set up a deposit of beads and pearls in Khartoum to be traded for local goods, particularly ivory. In 1863 Miani was welcomed in Vienna by the Austrian Geographic Society and presented to Franz Joseph I of Austria, who offered to finance a new expedition. However, news that Speke and Grant had discovered the sources of the Nile disrupted these plans.[1]

Miani was given 1,000 florins by Franz Joseph to return to Cairo, where he published a map in January 1864 that attempted to prove (incorrectly) that the river flowing from Lake Victoria was not the Nile but a tributary of the Baḥr el-Ghazāl, and the real sources of the river were further east, near the Patico mountains. He continued to promote his theories in writings and lectures. In 1865 Victor Emmanuel made him a knight of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus and promised to help a new expedition.[1]

Miani returned to Cairo, where he was given approval and a steamboat but no other help. He went to Constantinople, where he was given help in publishing a memoir to Roderick Murchison, president of the Royal Geographical Society of London.[1] He was 59 when the Khedive Isma'il Pasha named him director of the Zoological Garden of Khartoum.[8] The position paid 10 soldi a month. He tried to arrange further income by conducting research for some European museums on a commission basis, working for traders, and undertaking economic investigations for the cities of Trieste and Venice.[1]

Third Nile expedition (1871–1872)

Miani returned to Egypt with an agreement to accompany a trading company in an expedition to the Mangbetu region in search of ivory.[1] He set out again for the south at the age of 61, although his health was poor.[8] The expedition left Khartoum on 15 May 1871, but was delayed for three months at Gaba-Shambil at latitude 7°N.[1] He arrived in Lao in August, where he stayed until mid-September, and was with the Ajar tribe in October, then passed the month of Ramadan at Farial on the Rohl. From there, he turned south through Mittu country, crossing the zéribas of Nganna, Nyoli, Reggo, Urungana, and in the Luba country the zéribas of Mundu people on the Issu, a tributary of the upper Tonj River.[9]

In January Miani crossed the Congo-Nile Divide and entered the basin of the Uele River, which the local people called the Kibali. On 1 February 1872 he crossed the Uele between the confluences of the Dungu River in the east and the Duru River upstream of the confluence of the Gada River with the Uele. In February he reached the zériba of Monfa, where the chief was Kupa, son of Degberra, and where the Ghattas company had a trading post.[9] Miani was exhausted, and rested in Monfa for two months. When new resources arrived Miani continued on to Amamba, ruled by Sultan Kuffa, where he obtained food.[1]

Miani left Amamba and on 29 April 1872 crossed the Gada River, a left tributary of the Uele. On 1 May 1872 he arrived at Nangazizi[lower-alpha 2], the base of chief Mbunza, where he rested until 25 May 1872. From there the expedition crossed the country of the South Zande people and reached the Mangbetu-Azande border on 27 May 1872.[9] After passing passed through Abissenga, crossing the sultanate of Mangià, and passing through Angaria, on 3 July 1872 Miani arrived in Bakangoi. At this point his escort refused to go further.[1] On his journey from Mbunza to Bakangoi he noted that the streams generally drained north into the Uele River. The heavy rainfall filled the streams and marshes and made travelling difficult.[10]

Miani stayed at Bakangoi from 3 July 1872 to 16 September 1872. The sultan was greatly pleased with a present of a looking glass, and told him much about the lands to the south and west. Based on interviews with the sultan and his subjects he drew a sketch map of the region. The map shows two lakes where the Congo River crosses the equator. One lake is called the "Ghango" and the other is not named but said to be the source of the Zaire (Congo) and Ogowai.[10]

On 16 September 1872 the expedition began the return journey. On 17 September they reached Gandhuo on the Mamopoli, a left tributary of the Poko River. They left on 20 September and at the end of September reached Bangoi, near the Tele River, where they stayed for the whole month of October. In the second half of November, walking in short stages, they reached Mbunsa's residence at Tangasi (Nangazizi), south of Niangara, for the second time.[9] Miani died there on 21 November 1872 from a combination of fatigue, dysentery and necrosis of the arm. He was buried there, but his tomb was soon dug up again by the local people. Later Romolo Gessi managed to obtain the bones, which were given to the Italian Geographic Society.[1]

Achievements

Miani was among the first Europeans to reach the Uele region, others being the German botanist and ethnologist Georg August Schweinfurth, who discovered the Uele River in 1870, and Wilhelm Junker (1840–1892), a Russian explorer of German origins, who explored the Bomu-Uele region thoroughly in 1871.[11] Miani was the first European to mention the Barambu, Makere and Ababua peoples. He was the first to report the existence to the northwest, beyond the Ababua, of the Abandya, a third group of Zande people, whom Junker met on the lower Uele eight years later.[9]

Miani was the first to note the existence of the Tele, Poko and Makongo tributaries entering the Bomokandi from the south. He was the first to note that the lower reaches of the Bomokandi flowed north-northwest, so it must be a tributary of the Uele, which therefore had a much greater flow than at the point where Schweinfurth had crossed it in 1870. This showed that Schweinfurth's hypotheses that the Uele was the upper part of the Chari or Benue must be wrong. He was the first to report the Bima River crossing the Ababua territory.[9]

Legacy

In his writings Miani condemned slavery, but he profited from the protection of the merchant's troops and approved of their brutal treatment of the local people. He implicitly assumed that Europeans were superior to Africans and had the right to take possession of their lands.[12] His description of the tribes in the Bahr-el-Ghazal area was based on what he had been told rather than personal experience.[5]

Miani collected 1,800 objects on his first Nile expedition, and donated almost all of them to his adopted city of Venice.[7] The collection was displayed at the Casa dell'Industria in 1862. In 1866 it was transferred to the Museo Correr, and in 1880 was transferred to the Palazzo Fondaco dei Turchi, now the Museo di Storia Naturale di Venezia.[2]

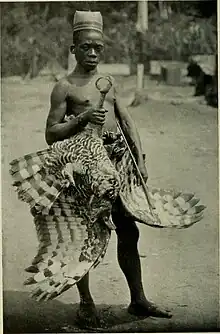

On his last journey Miani purchased two young Aka people in exchange for a dog and a calf. They were pygmy peoples who were respectively 4 feet 4 inches (1.32 m) and 4 feet 8 inches (1.42 m) high.[13] The crates of material he had collected were brought to Italy after his death, as were the two young Aka men, for exhibition in Europe.[1] The smaller collection from his last expedition, including both cultural artifacts and human remains, was donated to the Italian Geographical Society. Later it was transferred to the Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome.[2]

Publications

- Diari e carteggi (1858–1872). Longanesi, Milano, 1973.

- Il viaggio di Giovanni Miani al Monbuttu: note coordinate dalla Società geografica italiana. Giuseppe Civelli, Roma, 1875.

- Nouvelle carte du Bassin du Nil: indiquant la commune origine de ce Fleuve avec les rivières du Zanguebar. Kaeppelin et Cie, Parigi, 1858.

- Un torneo a Tolemaide: miscellanea poetica. Andreola, Venezia, 1843.

Notes

- The British explorer John Hanning Speke saw Miani's name carved on the tamarind tree during his 1862/1863 exploration of the great lakes and upper Nile.[6]

- Nangazizi, or Tangasi, was also called Munza after its chief, Mbunza.

Citations

- Surdich 2010.

- Cormack 2017.

- Palumbo 2003, p. 134 fn2.

- Bompiani 1891, p. 15.

- Palumbo 2003, p. 129.

- Bompiani 1891, p. 14.

- Exhibitions : Collecting to astonish...

- Bompiani 1891, p. 16.

- Omasombo Tshonda 2011, p. 136.

- The Welle River 1878, p. 48.

- Ergo 2013, p. 1.

- Palumbo 2003, p. 130.

- Akka 1911 Britannica, p. 456.

Sources

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 01 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 456–457.

- Bompiani, Sofia (1891), "II. Giovanni Miani", Italian Explorers in Africa, Religious tract society

- Cormack, Zoe (2017), "Violence, globalization and the trade in "ethnographic" artefacts in nineteenth-century Sudan", Journal for Art Market Studies, Berlin Forum Kunst und Markt, ISSN 2511-7602, retrieved 2020-12-09

- Egli, Dr. J. J. (1867), "Die Entdeckung der Nilquellen" (PDF), Vierteljahresschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, Zurigo, retrieved 2020-12-08

- Ergo, André-Bernard (2013), "Les postes fortifiés de la frontière Nord de l'État Indépendant du Congo" (PDF), Histoire du Congo, retrieved 2020-08-27

- Exhibitions : Collecting to astonish, collecting for research, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, retrieved 2020-12-09

- "Giovanni Miani", veneto.eu, retrieved 2020-12-08

- Omasombo Tshonda, Jean (2011), Haut-Uele : Trésor (PDF) (in French), Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, ISBN 978-2-8710-6578-4, retrieved 2020-12-12

- Palumbo, Patrizia (17 November 2003), A Place in the Sun: Africa in Italian Colonial Culture from Post-Unification to the Present, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-93626-3

- Surdich, Franceso (2010), "Miani, Giovanni", Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 74, pp. 100–104

- "The Welle River", The Geographical Magazine, Trübner, 1878

Further reading

- Civiletti, Graziella (1991), Un veneziano in Africa. Vita e viaggi di Giovanni Miani secondo i suoi diari (Gli esploratori italiani negli ultimi due secoli) (in Italian), Rai Libri, p. 123, ISBN 8839706380

- Romanato, Gianpaolo, ed. (2006), Giovanni Miani. The Venetian contribution to knowledge of Africa, p. 348, ISBN 9788865660386

- Thomas, Harold Beken (1939), Giovanni Miani and the White Nile