Hexactinellid

Hexactinellid sponges are sponges with a skeleton made of four- and/or six-pointed siliceous spicules, often referred to as glass sponges. They are usually classified along with other sponges in the phylum Porifera, but some researchers consider them sufficiently distinct to deserve their own phylum, Symplasma. Some experts believe glass sponges are the longest-lived animals on earth;[2] these scientists tentatively estimate a maximum age of up to 15,000 years.

| Hexactinellid sponges Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

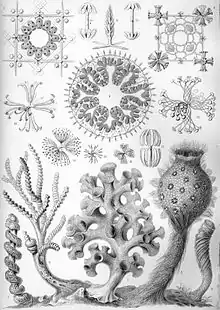

| "Hexactinellae" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Porifera |

| Class: | Hexactinellida Schmidt, 1870 |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Biology

Glass sponges are relatively uncommon and are mostly found at depths from 450 to 900 metres (1,480 to 2,950 ft) below sea level. Although the species Oopsacas minuta has been found in shallow water, others have been found much deeper. They are found in all oceans of the world, although they are particularly common in Antarctic and Northern Pacific waters.[3]

They are more-or-less cup-shaped animals, ranging from 10 to 30 centimetres (3.9 to 11.8 in) in height, with sturdy skeletons made of glass-like silica spicules, fused to form a lattice.[4][5] The body is relatively symmetrical, with a large central cavity that, in many species, opens to the outside through a sieve formed from the skeleton. Some species of glass sponges are capable of fusing together to create reefs or bioherms. They are generally pale in colour, ranging from white to orange.[3]

Much of the body is composed of syncitial tissue, extensive regions of multinucleate cytoplasm. The epidermal cells characteristic of other sponges are absent, being replaced by a syncitial net of amoebocytes, through which the spicules penetrate. Unlike other sponges, they do not possess the ability to contract.[3]

Their body comprises three parts: the inner and outer peripheral trabecular networks, and the choanosome, which is used for feeding purposes. The choanosome acts as the mouth for the sponge while the inner and outer canals that meet at the choanosome are passages for the food, creating a consumption path for the sponge.[6]

All hexactinellids have the potential to grow to different sizes, but the average maximum growth is estimated to be around 32 centimeters long. Some grow past that length and continue to extend their length up to 1 meter long. The estimated life expectancy for hexactinellids that grow around 1 meter is approximately 200 years (Plyes).

Glass sponges possess a unique system for rapidly conducting electrical impulses across their bodies, making it possible for them to respond quickly to external stimuli.[7] Species like "Venus' flower basket" have a tuft of fibers that extends outward like an inverted crown at the base of their skeleton. These fibers are 50 to 175 millimetres (2.0 to 6.9 in) long and about the thickness of a human hair.

Glass sponges are different from other sponges in various other ways. For example, most of the cytoplasm is not divided into separate cells by membranes but forms a syncytium or continuous mass of cytoplasm with many nuclei (e.g., Reiswig and Mackie, 1983).

These creatures are long-lived, but the exact age is hard to measure; one study based on modelling gave an estimated age of a specimen of Scolymastra joubini as 23,000 years (with a range from 13,000 to 40,000 years). However, due to changes in sea levels since the Last Glacial Maximum, its maximum age is thought to be no more than 15,000 years,[8] hence its listing of c. 15,000 years in the AnAge Database.[9] The shallow-water occurrence of hexactinellids is rare worldwide. In the Antarctic, two species occur as shallow as 33 meters under the ice. In the Mediterranean, one species occurs as shallow as 18 metres (59 ft) in a cave with deep water upwelling (Boury-Esnault & Vacelet (1994))

Staurocalyptus sp.

Staurocalyptus sp. Various hexactinellid sponges.

Various hexactinellid sponges. Hexactinellid sponge on a xenophorid gastropod.

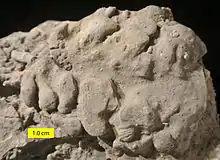

Hexactinellid sponge on a xenophorid gastropod. Pattersonia ulrichi Rauff, 1894; an Ordovician hexactinellid sponge from near Cincinnati, Ohio.

Pattersonia ulrichi Rauff, 1894; an Ordovician hexactinellid sponge from near Cincinnati, Ohio.

Reefs

The sponges form reefs (called sponge reefs) off the coast of British Columbia, southeast Alaska and Washington state,[10] which are studied in the Sponge Reef Project. Reefs discovered in Hecate Strait, British Columbia, have grown to up to 7 kilometres long and 20 metres high. Prior to these discoveries, sponge reefs were thought to have died out in the Jurassic period.[11][12]

Reports of glass sponges have also been recorded on the HCMS Saskatchewan and HCMS Cape Breton wrecks off the coast of Vancouver Island.

Classification

The earliest known hexactinellids are from the earliest Cambrian or late Neoproterozoic eras. They are fairly common relative to demosponges as fossils, but this is thought to be, at least in part, because their spicules are sturdier than spongin and fossilize better. Like almost all sponges, the hexactinellids draw water in through a series of small pores by the whip-like beating of a series of hairs or flagella in chambers which in this group line the sponge wall.

The class is divided into two subclasses and several orders:[13]

Class Hexactinellida

- Subclass Amphidiscophora

- Order Amphidiscosida

- Order †Hemidiscosa[14]

- Order †Reticulosa[14]

- Subclass Hexasterophora

- Incertae sedis

- Dactylocalycidae Gray, 1867

- Order Lychniscosida

- Order Lyssacinosida

- Order Sceptrulophora

- Incertae sedis

See also

References

- Brasier, Martin; Green, Owen; Shields, Graham (April 1997). "Ediacarian sponge spicule clusters from southwestern Mongolia and the origins of the Cambrian fauna" (PDF). Geology. 25 (4): 303–306. Bibcode:1997Geo....25..303B. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0303:ESSCFS>2.3.CO;2.

- "Hexactinellid sponge (Scolymastra joubini) longevity, ageing, and life history". genomics.senescence.info. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- "Glass Sponges, the Living Ornaments of the Deep Sea". Schmidt Ocean Institute. 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is a glass sponge?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- "Gale - Institution Finder".

- "Nervous sponge".

- Susanne Gatti (2002). "The Role of Sponges in High-Antarctic Carbon and Silicon Cycling - a Modelling Approach" (PDF). Ber. Polarforsch. Meeresforsch. 434. ISSN 1618-3193. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- "Hexactinellid information from the AnAge Database".

- Stiffler, Lisa (2007-07-27). "Reef of glass sponges found off Washington's coast". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- "B.C.'s Reefs Among Science's Great Finds". Georgia Straight Vancouver's News & Entertainment Weekly. 2005-02-24. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- "Diving deep for glass sponges". CBC Radio. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- "Hexactinellida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species.

- Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology Part E, Revised. Porifera, Volume 3: Classes Demospongea, Hexactinellida, Heteractinida & Calcarea, xxxi + 872 p., 506 fig., 1 table, 2004, available here. ISBN 0-8137-3131-3.

External links

Media related to Hexactinellida at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hexactinellida at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Hexactinellida at Wikispecies

Data related to Hexactinellida at Wikispecies

- Falcucci, Giacomo; Amati, Giorgio; Fanelli, Pierluigi; Krastev, Vesselin K.; Polverino, Giovanni; Porfiri, Maurizio; Succi, Sauro (July 2021). "Extreme flow simulations reveal skeletal adaptations of deep-sea sponges". Nature. 595 (7868): 537–541. arXiv:2305.10901. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03658-1. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34290424. S2CID 236176161.