Glutamate racemase

In enzymology, glutamate racemase (MurI with a capital i) (EC 5.1.1.3) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

- L-glutamate D-glutamate

| Glutamate Racemase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 5.1.1.3 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9024-08-2 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Hence, this enzyme RacE has one substrate, L-glutamate, and one product, D-glutamate.

This enzyme belongs to the family of isomerases, specifically those racemases and epimerases acting on amino acids and derivatives, including proline racemase, aspartate racemase, and diaminopimelate epimerase.[1] This enzyme participates in glutamate metabolism that is essential for cell wall biosynthesis in bacteria.[2] Glutamate racemase performs the additional function of gyrase inhibition, preventing gyrase from binding to DNA.[3]

Glutamate racemase (MurI) serves two distinct metabolic functions: primarily, it is a critical enzyme in cell wall biosynthesis,[2] but also plays a role in gyrase inhibition.[3] The ability of glutamate racemase and other proteins to serve two distinct functions is known as "moonlighting".

Moonlighting background

Before the discovery of moonlighting proteins, it was generally believed by scientists that an enzyme only had one function which led to the concept of "one gene, one enzyme". However, this concept no longer applies in science after the discovery that some proteins consist of both major and minor functions. This led to numerous studies attempting to relate the two functions to each other. The minor functions of these unique enzymes are called moonlighting functions, in which a protein can have a secondary functions not dependent upon the main function. These two functions of the moonlighting protein are found in a single polypeptide chain. Proteins that are multifunctional are not included due to gene fusion, families of homologous proteins, splice variants or promiscuous enzyme activities. The enzyme glutamate racemase (MurI) is an example of a moonlighting protein, functioning both in bacterial cell wall biosynthesis as well as in gyrase inhibition.

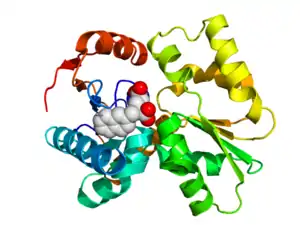

Structure

The dimensions of MurI is approximately 35 Å × 40 Å × 45 Å and consists of two compact domains of α/β structure.[1][4] With the active site in between the two domains, the N-terminal domain contains residues 1-97 and 207-264 while the C-terminal domain includes residues 98-206.[1] This allows the enzyme to produce L-isomer from D-glutamate. Also, the N-domain is composed of five-stranded β-sheets compared to four-stranded β-sheets of C-domain.[1] These structural specifications are not identical between MurI of different species; S. pyogenes and B. subtilis actually possess the most structurally similar MurI enzymes yet found. It is also not rare to find MurI as a dimer.

The active site, as it is evenly between the N-domain and C-domain, is also between the two cysteine residues. It is accessible to solvents, as several water molecules, such as W1, are found in the active site. In some species, the active site also incorporates sulfate ions to undergo hydrogen bonding on the amide backbone and the side chains.[1][5]

Function

Bacterial wall synthesis

| Glutamate Racemase | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | murI | ||||||

| Entrez | 948467 | ||||||

| RefSeq (Prot) | NP_418402 | ||||||

| UniProt | P22634 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 5.1.1.3 | ||||||

| Chromosome | genome: 4.16 - 4.16 Mb | ||||||

| |||||||

Glutamate racemase is a bacterial enzyme that is encoded by the murI gene. This enzyme is most commonly known as being responsible for the synthesis of bacterial cell walls. Through experimentation it was found that this enzyme is able to construct these cell walls by synthesizing D-glutamate from L-glutamate through racemization.[4] D-glutamate is a monomer of the peptidoglycan layer in prokaryotic cell walls. Peptidoglycan is an essential structural component of the bacterial cell wall. The peptidoglycan layer is also responsible for the rigidity of the cell wall.[6] This process, in which MurI helps catalyze the interconversion of glutamate enantiomers, like L-Glutamate, into the essential D-glutamate, is also cofactor independent. As such it can proceed without needing an additional source, which would bind to an allosteric site, altering the enzyme shape to assist in catalyzing the reaction.[7] Murl involves a two-step process to catalyze the glutamate enantiomers to D-glutamate. The first step is a deprotonation of the substrate to form an anion.[7] Subsequently, the substrate gets reprotonated. Once the glutamate is in the active site of the enzyme it undergoes a very large conformational change of its domains. This change helps superimpose the two catalytic cysteine residues, Cys73 and Cys184, located on either sides of the substrate at equal positions. Those domains mentioned earlier are symmetric and this symmetry suggests that this racemase activity of the protein may have evolved from gene duplication.[5] Due to this main function of biosynthesis of bacterial cell walls MurI has been targeted as an antibacterial in drug discovery.[8]

Gyrase inhibition

Along with its main function of cell wall biosynthesis, the moonlighting protein glutamate racemase also functions independently as a gyrase inhibitor.[2] Present in certain forms of bacteria, MurI reduces the activity of DNA gyrase by preventing gyrase from binding to DNA.[2] When gyrase binds to DNA, the enzyme decreases the tension in the DNA strands as they are unwound and causes the strands to become supercoiled.[9] This is a critical step in DNA replication in these cells which results in the reproduction of bacterial cells.[10] The presence of glutamate racemase in the process inhibits gyrase from effectively binding to DNA by deforming the shape of the enzyme's active site. It essentially disallows gyrase from catalyzing the reaction that coils unwinding DNA strands.[10]

This function of MurI was discovered experimentally. DNA gyrase was incubated with the MurI enzyme and then added to a sample of DNA; the results of this experiment showed inhibition of supercoiling activity when MurI was present.[2] The cell wall biosynthesis function of MurI is not directly related to its moonlighting function. MurI's ability to inhibit gyrase binding can proceed independently of its main function.[2] This means that DNA gyrase, in turn, will not have any effect on MurI's racemization, which was confirmed in a study of the racemization with and without the presence of DNA gyrase.[2] In an experimental analysis, it was determined that MurI employs the use of two different enzymatic active sites for its two functions. This was shown by the inclusion of the racemase substrate L-glutamate in an assay with the separated gyrase inhibition site. The gyrase inhibition occurs in both supercoiling and relaxing activities of the DNA gyrase, and the study concluded that the inhibition activity was able to proceed, unchanged, in the presence of the racemase substrate.[10] This dictates that the two functions can be carried out independently of each other, on non-overlapping sites, making MurI a true moonlighting protein.[2] Mutant forms of MurI that are unable to exhibit their racemase function, no matter how compromised their racemase abilities were, were still proven through a study to be able to perform the DNA gyrase inhibition, with comparable results to a non-mutated form of MurI.[10]

Relationship between main and moonlighting functions

Glutamate racemase (MurI) provides multiple functions for bacterial cells. MurI is an enzyme which is primarily known for its role in synthesizing bacterial cell walls. While performing the function of cell wall synthesis, MurI also acts as a gyrase inhibitor, preventing gyrase from binding to DNA. The two processes have been shown two be unrelated.[2] In order to ascertain the effects of gyrase inhibition on cell wall synthesis, the efficiency of the conversion of D-glutamate to L-glutamate was measured while varying the concentration of DNA gyrase. Conversely, the effects of cell wall production on gyrase inhibition were discovered by varying the concentration of the racemization substrate.[2] The results of these experiments conclude that there is no significant effect of racemization on gyrase inhibition or vice versa.[2] The two functions of MurI act independently of each other reaffirming the fact that MurI is a moonlighting protein.

Relationship to active site

Glutamate racemase is known to use its active site to undergo racemization and participate in the cell wall biosynthesis pathway of bacteria.[2] Based on homology to other racemases and epimerases, glutamate racemase is thought to employ two active site cysteine residues as acid/base catalysts.[7] Surprisingly however, substituting either of the two residues with serine did not appreciable change the rate of the reaction significantly; the kcat value remained within .3% to 3% compared to the wild-type enzyme.[7] From previous studies, it is most likely that the active site of MurI that performs racemization is not the same active site that undergoes gyrase inhibition. In order to ascertain the effects of gyrase inhibition on cell wall synthesis, the efficiency of the conversion of D-glutamate to L-glutamate was measured while varying the concentration of DNA gyrase. Conversely, the effects of cell wall production on gyrase inhibition were discovered by varying the concentration of the racemization substrate. It has been shown that the two functions are neutral to each other.[2] In other words, racemization substrates are neutral to gyrase inhibition, and DNA gyrase has no effect on racemization. This explains how glutamate racemase in certain bacteria, such as Glr from B. subtilis, do not inhibit gyrase;[12] if one active site is involved with both functions, this independence would not be possible. Consequently, a different site of MurI, distant from its active site, is involved in interacting with gyrase.[2]

Enzyme regulation

This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.[13]

Application

Glutamate racemase has emerged as a potential antibacterial target since the product of this enzyme, D-glutamate, is an essential component of bacterial walls. Inhibiting the enzyme will prevent bacterial wall formation and ultimately result in lysis of the bacteria cell by osmotic pressure. Furthermore, glutamate racemase is not expressed nor is the product of this enzyme, D-glutamate is normally found in mammals, hence inhibiting this enzyme should not result in toxicity to the mammalian host organism.[5] Possible inhibitors to MurI includes aziridino-glutamate that would alkylate the catalytic cysteines; N-hydroxy glutamate that by mimicking Wat2 (the bound water molecule that interacts with glutamate amino group) would prevent binding of the substrate;[5] or 4-substituted D-glutamic acid analogs bearing aryl-, heteroaryl-, cinnamyl-, or biaryl-methyl substituents that would also prevent binding of substrate.[5]

References

- Kim KH, Bong YJ, Park JK, Shin KJ, Hwang KY, Kim EE (September 2007). "Structural basis for glutamate racemase inhibition". J. Mol. Biol. 372 (2): 434–43. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.003. PMID 17658548.

- Sengupta S, Ghosh S, Nagaraja V (September 2008). "Moonlighting function of glutamate racemase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: racemization and DNA gyrase inhibition are two independent activities of the enzyme". Microbiology. 154 (Pt 9): 2796–803. doi:10.1099/mic.0.2008/020933-0. PMID 18757813.

- Reece RJ, Maxwell A (1991). "DNA gyrase: structure and function". Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 26 (3–4): 335–75. doi:10.3109/10409239109114072. PMID 1657531.

- Hwang KY, Cho CS, Kim SS, Sung HC, Yu YG, Cho Y (May 1999). "Structure and mechanism of glutamate racemase from Aquifex pyrophilus". Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 (5): 422–6. doi:10.1038/8223. PMID 10331867. S2CID 10925922.

- Ruzheinikov SN, Taal MA, Sedelnikova SE, Baker PJ, Rice DW (November 2005). "Substrate-induced conformational changes in Bacillus subtilis glutamate racemase and their implications for drug discovery". Structure. 13 (11): 1707–13. doi:10.1016/j.str.2005.07.024. PMID 16271894.

- Schleifer KH, Kandler O (December 1972). "Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications". Bacteriol Rev. 36 (4): 407–77. doi:10.1128/MMBR.36.4.407-477.1972. PMC 408328. PMID 4568761.

- Glavas S, Tanner ME (May 2001). "Active site residues of glutamate racemase". Biochemistry. 40 (21): 6199–204. doi:10.1021/bi002703z. PMID 11371180.

- Lundqvist T, Fisher SL, Kern G, Folmer RH, Xue Y, Newton DT, Keating TA, Alm RA, de Jonge BL (June 2007). "Exploitation of structural and regulatory diversity in glutamate racemases". Nature. 447 (7146): 817–22. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..817L. doi:10.1038/nature05689. PMID 17568739. S2CID 4408683.

- Sengupta S, Shah M, Nagaraja V (2006). "Glutamate racemase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits DNA gyrase by affecting its DNA-binding". Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (19): 5567–76. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl704. PMC 1635304. PMID 17020913.

- Sengupta S, Nagaraja V (February 2008). "Inhibition of DNA gyrase activity by Mycobacterium smegmatis MurI". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279 (1): 40–7. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01005.x. PMID 18177305.

- PDB: 2OHV; Kim KH, Bong YJ, Park JK, Shin KJ, Hwang KY, Kim EE (September 2007). "Structural basis for glutamate racemase inhibition". J. Mol. Biol. 372 (2): 434–43. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.003. PMID 17658548.

- Ashiuchi M, Kuwana E, Komatsu K, Soda K, Misono H (June 2003). "Differences in effects on DNA gyrase activity between two glutamate racemases of Bacillus subtilis, the poly-gamma-glutamate synthesis-linking Glr enzyme and the YrpC (MurI) isozyme". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 223 (2): 221–5. doi:10.1016/s0378-1097(03)00381-1. PMID 12829290.

- T. Selwood; E. K. Jaffe. (2011). "Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519 (2): 131–43. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. PMC 3298769. PMID 22182754.

Further reading

- Glaser L (1960). "Glutamic acid racemase from Lactobacillus arabinosus". J. Biol. Chem. 235 (7): 2095–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)69369-X. PMID 13828348.