Gold mining in the United States

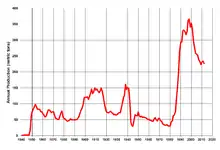

In the United States, gold mining has taken place continually since the discovery of gold at the Reed farm in North Carolina in 1799. The first documented occurrence of gold was in Virginia in 1782.[1] Some minor gold production took place in North Carolina as early as 1793, but created no excitement. The discovery on the Reed farm in 1799 which was identified as gold in 1802 and subsequently mined marked the first commercial production.[2]

The large scale production of gold started with the California Gold Rush in 1848.

The closure of gold mines during World War II by the War Production Board Limitation Order No. 208 in autumn 1942 was a major impact on the production until the end of the war.[3]

US gold production greatly increased during the 1980s, due to high gold prices and the use of heap leaching to recover gold from disseminated low-grade deposits in Nevada and other states.

In 2019 the United States produced 200 tonnes (6.4 million troy ounces) of gold (down from 210 tonnes in 2018) from 12 states, worth about US$8.9 billion, and 6.1% of world production, making it the fourth-largest gold-producing nation, behind China, Australia and Russia. Most gold produced today in the US comes from large open-pit heap leach mines in the state of Nevada. The US is a net exporter of gold.[4][5]

Gold mining by state

Alabama

Gold was discovered in Alabama about 1830, shortly following the Georgia Gold Rush. The principal districts were the Arbacoochee district in Cleburne County, mostly from placer deposits, and the Hog Mountain district in Tallapoosa County, which produced 24,000 troy ounces (750 kg) from veins in schist.[6]

Alaska

Russian explorers discovered placer gold in the Kenai River in 1848, but no gold was produced. Gold mining started in 1870 from placers southeast of Juneau.[7] Alaska produced a total of 40,300,000 troy ounces (1,250,000 kg) of gold from 1880 through the end of 2007. In 2015 Alaskan mines produced 873,984 troy ounces (27,183.9 kg) of gold, 12.7% of US production.[8] The largest gold producer is the Fort Knox mine, a large open pit and cyanide leaching operation in the Fairbanks mining district, which in 2019 produced 200,263 gold equivalent ounces.[9] The Pogo (159,344 ounces) and Kensington (127,914 ounces)[10] gold mines and the Greens Creek polymetallic mine (56,625 ounces) accounted for the remainder of 2019 gold production.[11]

Arizona

Arizona has produced more than 16 million troy ounces (498 tonnes) of gold.

Gold mining in Arizona reportedly began in 1774 when Spanish priest Manuel Lopez directed Papago Indians to wash gold from gravel on the flanks of the Quijotoa Mountains, Pima County. Gold mining continued there until 1849, when the Mexican miners were lured away by the California Gold Rush. Other gold mining under Spanish and Mexican rule took place in the Oro Blanco district of Santa Cruz County, and the Arivaca district, Pima County.[12]

Mountain man Pauline Weaver discovered placer gold on the east side of the Colorado River in 1862. Weaver's discovery started the Colorado River Gold Rush to the now ghost town of La Paz, Arizona and other locations along the river in the ensuing years.

The most prominent of these were those of the San Francisco district, which includes the towns of Oatman, Bullhead City and Katherine in Mohave County was discovered in 1863 or 1864, but saw little activity until a rush to the district occurred in 1902. The district produced 2.0 million ounces of gold through 1959.[13]

The gold-bearing quartz veins of the Vulture Mine, southwest of Wickenburg, in Maricopa County were discovered in 1863. The mine produced 366,000 troy ounces (11,400 kg) of gold through 1959.[14]

The last gold mine to operate in Arizona was the Gold Road mine at Oatman, which shut down in 1998. Patriot Gold is exploration drilling at the Moss mine at Oatman.[15]

In 2006, all of Arizona's gold production came as a byproduct of copper mining.

California

Spanish prospectors found gold in the Potholes district between 1775 and 1780, along the Colorado River, in present Imperial County, California, about ten miles northeast from Yuma, Arizona. The gold was recovered from dry placers. Other placer deposits on the west bank of the Colorado River were quickly found, including the Picacho and Cargo Muchacho districts.

Placer gold deposits were found at San Ysidro in San Diego County in 1828, San Francisquito Canyon and Placerita Canyon in Los Angeles County in 1835 and 1842, respectively

Major gold mining in California began during the California Gold Rush. Gold was found by James Marshall at Sutters Mill, property of John Sutter, in present-day Coloma. In 1849, people started hearing about the gold and after just a few years San Francisco's population increased to thousands.

Gold production in California peaked in 1852, at 3.9 million troy ounces (121 tonnes) produced in that year. But the placer deposits worked in the early years were quickly exhausted, and production crashed. Hardrock mining (in California called quartz mining) began in 1849, and placer mining by hydraulic mining began in 1852.

Despite the new mining methods, by 1865 production was 867,000 troy ounces (27,000 kg), less than one-quarter of peak production.

Production sank to 412,000 troy ounces (12,800 kg) in 1929, but then soared to more than 1,400,000 troy ounces (44,000 kg) for each year 1939 through 1941, after the price was raised from $20.67 to $35 per ounce.

However, the federal government, in War Production Board Order L-208, ordered gold mines closed, to free up resources for the war effort during World War II, and production fell to 148,000 troy ounces (4,600 kg) in 1943. Post-war gold production never reached the peak of the early 1940s, as inflation and the fixed price of gold eroded its value.[16]

The largest gold-mining district in California is the famous Mother Lode of the Sierra Nevada. Found in the early 1850s, the lode is a zone one to four miles wide and running 120 miles northwest–southeast from El Dorado County in the north, through Amador, Calaveras, and Tuolumne counties, to Mariposa County in the south. The gold of the Mother Lode is in quartz veins within phyllite, schist, slate, and greenstone. Through 1959, the Mother Lode produced about 13.3 million troy ounces (414 tonnes) of gold.[17]

The second-largest gold-mining district in California was Grass Valley-Nevada City district in Nevada County. Gold in Holocene gravels was found in 1850, followed a few years later by hydraulic mining of Tertiary gravels. By 1880, most of the mining had shifted to lode deposits, such as the Empire Mine. Through 1959, the district produced 10.4 million troy ounces (323 tonnes) of lode gold, and 2.2 million troy ounces (68.4 tonnes) of placer gold.[18]

The rich placer deposits of the Columbia Basin-Jamestown-Sonora district were found in 1853. Almost all the gold was found at the base of Quaternary gravels, but some drift mines were worked in Tertiary gravels. Total production was about 5.9 million troy ounces (183 tonnes) of gold.[19]

The Rand Mining District near Randsburg in the Mojave Desert was formed in 1895 around the Yellow Aster Mine. It was the largest gold mining district in Southern California.[20]

In 2018 California produced 140,000 troy ounces (4,400 kg) of gold from its only operating mine, the Mesquite mine (owned by Equinox Gold Corp.) in Imperial County, which restarted active mining in 2007, having been inactive since 2001.[21][22]

Colorado

Gold was discovered in 1858 during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush in the vicinity of present-day Denver in 1858, but the deposits were small. The first important gold discoveries in Colorado were in the Central City-Idaho Springs district in January 1859.

Only one Colorado mine continues to produce gold, the Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine at Victor near Colorado Springs, an open-pit heap leach operation owned by Newmont Mining Corporation, which produced 360,000 troy ounces (11,000 kg) of gold in 2018.[23]

Florida

Small amounts of gold were mined commercially in North Eastern Florida during the late 19th Century, at the site where Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park is located today. No records are extant on the amount of gold produced, but the find was insufficient to keep the operation running commercially, and the small amount of pay dirt was depleted within a matter of months.[24]

Georgia

Georgia is credited with a total historical production of 871,000 troy ounces (27,100 kg) of gold from 1830 through 1959.[25] Although historically important, the state is not currently a gold producer.

Idaho

Gold was first discovered in Idaho in 1860, in Pierce at the juncture where Canal Creek meets Orofino Creek.

The leading historical gold-producing district is the Boise Basin in Boise County, which was discovered in 1862 and produced 2.9 million troy ounces (90.2 tonnes), mostly from placers.[26]

The French Creek-Florence district in Idaho County began in the 1860s, and has produced about 1 million troy ounces (31 tonnes) from placers.

The Silver City district in Owyhee County began producing in 1863, and made over 1 million troy ounces (31 tonnes), mostly from lode deposits.

The Coeur d’Alene district in Shoshone County has made 44,000 troy ounces (1,400 kg) of gold as byproduct to silver mining.[27]

In 2006, active gold mines in Idaho included the Silver Strand mine and the Bond mine.[28]

Maryland

Gold was reported in Maryland as early as 1830, but no production resulted. Placer gold was discovered at Great Falls near Washington, DC in 1861 during the American Civil War by Union soldiers from California. After the war a number of mines were opened on gold-bearing quartz veins in Montgomery County. No gold production has been reported since 1951. Total production was about 6,000 troy ounces (190 kg).[29]

Michigan

Approximately 29,000 troy ounces (900 kg) of gold were produced from the Ropes gold mine northeast of Ishpeming in Marquette County, Michigan. The underground mine, originally operated from 1880 to 1897, and reopened from 1983 to 1989,[30] extracted gold from quartz veins in peridotite.[31]

Montana

Gold was first discovered in Montana in 1852, but mining did not begin until 1862, when gold placers were discovered at Bannack, Montana in 1862. The resulting gold rush resulted in more placer discoveries, including those at Virginia City in 1863, and at Helena and Butte in 1864.[32] In 1867, the Atlantic Cable Quartz Lode was located.

The Butte district, although mined primarily for copper, produced 2.9 million ounces (91 tonnes) of gold through 1990, almost all as a byproduct of copper production.[33]

Current active hardrock gold mines include the Montana Tunnels mine, and the Golden Sunlight mine. Active gold placers include the Browns Gulch placer and the Confederate Gulch placer. Gold is also produced from three platinum mines in the Stillwater igneous complex: the Stillwater mine, the Lodestar mine, and the East Boulder Project.[34]

Nevada

Nevada is the leading gold-producing state in the nation, in 2018 producing 5,581,160 troy ounces (173.6 tonnes), representing 78% of US gold and 5.0% of the world's production. Much of the gold in Nevada comes from large open pit mining and with heap leaching recovery. Some of the world's major mining companies, including Newmont Mining, Barrick Gold and Kinross Gold, operate gold mines in the state. Active major mines include Cortez, Twin Creeks, Betz-Post, Meikle, Marigold, Round Mountain, Jerritt Canyon and Getchell.[35][36]

Newmont and Barrick operate the largest mining operations, on the prolific Carlin Trend, one of the world's richest mining districts.[35]

New Mexico

Gold was first discovered in New Mexico in 1828 in the “Old Placers” district in the Ortiz Mountains, Santa Fe County, New Mexico. The placer gold discovery was followed by discovery of a nearby lode deposit.[37]

In 1877, two prospectors collected float in the area of the future Opportunity Mine near Hillsboro, New Mexico, which was assayed at $160 per ton in gold and silver. Soon, ore was discovered at the nearby Rattlesnake vein and a placer deposit of gold was found in November at the Rattlesnake and Wicks gulches. Total production prior to 1904 was about $6,750,000.[38]

In 2018 gold production in New Mexico came as a byproduct of copper mining from Freeport-McMoRan Inc.'s Chino mine, a large open pit copper mine in Grant County.[39]

North Carolina

North Carolina was the site of the first gold rush in the United States, following the discovery of a 17-pound (7.7 kg) gold nugget by 12-year-old Conrad Reed in a creek at his father's farm in 1799. The Reed Gold Mine, southwest of Georgeville in Cabarrus County, North Carolina produced about 50,000 troy ounces (1,600 kg) of gold from lode and placer deposits.[40]

Gold was produced from 15 districts, almost all in the Piedmont region of the state. Total gold production is estimated at 1.2 million troy ounces (37.3 tonnes).

Oregon

Although gold mines are spread over much of Oregon, almost all of the gold produced has come from two principal areas: the Klamath Mountains in southwest Oregon, including Coos, Curry, Douglas, Jackson and Josephine counties; and the Blue Mountains in northeast Oregon, mostly in Baker and Grant counties.

Prospectors from Illinois discovered placer gold in the Klamath Mountains of southwest Oregon in 1850, starting a rush to the area. Lode gold deposits were also discovered.

Pennsylvania

About 37,000 troy ounces (1,200 kg) of gold was produced from the Cornwall iron mine five miles south of Lebanon, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. Although the deposit produced iron since 1742, no gold was reported from the mine until 1878.[41]

South Carolina

South Carolina had a number of lode gold mines along the Carolina Slate Belt.[42]

The Haile deposit was discovered in Lancaster County in 1827, and at least 257,000 troy ounces (8,000 kg) of gold were extracted intermittently between then and 1942, when the gold mine was ordered closed as nonessential to the war effort. Beginning in 1951, the deposit was mined for associated sericite, which was used as a white filler.[43]

Gold is associated with silicic, kaolinitic, and pyritic alteration of greenschist-grade felsic metavolcanics.[44] The mine was reopened as an open pit in the 1980s, and operated until 1992. Kinross Gold Corporation's reclamation of the Haile site was nominated for a US Bureau of Land Management "Hardrock Mineral Environmental Award."

OceanGold Corp. restarted mining at the Haile deposit 2016. The company expects to produce an average of 126,700 ounces of gold per year for 13.25 years.[45]

The Brewer mine operated from 1828 to 1995, and is now a federal Superfund site.[46]

Kennecott Minerals operated the Ridgeway open-pit gold mine from 1988 to 1999, and the land is now being reclaimed by Kennecott.

The Barite Hill mine operated from 1990 to 1994.

South Dakota

The only operating gold mine in South Dakota is the Wharf mine, at Lead, an open pit heap leach operation operated by Coeur Mining that produced 109,000 ounces of gold in 2016.[47]

Tennessee

Placer gold was discovered on Coker Creek in Monroe County, Tennessee in 1827. The district produced about 9,000 troy ounces (280 kg).[48]

About 15,000 troy ounces (470 kg) of gold was recovered from the massive sulfide copper ores in the Copper Basin at Ducktown, Tennessee.

Texas

Some prospects have been excavated for gold on the Llano Uplift of central Texas. Gold prospects include the Heath mine and the Babyhead district, both in Llano County, and the Central Texas mine in Gillespie County. Gold production, if any, is not known.[49] Historically, the Lost Nigger Gold Mine may be in Texas.

Utah

Most gold produced in Utah today is a byproduct of the huge Bingham Canyon copper mine, southwest of Salt Lake City. In 2013, the Bingham Canyon mine produced 192,300 troy ounces (5,980 kg) of gold.[50] Over its life, Bingham Canyon has produced more than 23 million ounces (715 tonnes) of gold, making it one of the largest gold producers in the US.

The Barneys Canyon mine in Salt Lake County, the last primary gold mine to operate in Utah, stopped mining in 2001, but is still recovering gold from its heap leaching pads. Utah gold production was 460,000 troy ounces (14,000 kg) in 2006.[51]

Virginia

Washington

Gold was first discovered in Washington in 1853, as placer deposits in the Yakima Valley. Production from the state never exceeded 50,000 troy ounces per year until the mid-1930s, when large hard rock deposits were developed near the Chelan Lake and Wenatchee deposits in Chelan County, and the Republic deposit in Ferry County. Production through 1965 is estimated to be 2.3 million ounces.[52]

Wyoming

Gold was discovered at the South Pass-Atlantic City-Sweetwater district in present Fremont County in 1842. The placers were worked intermittently until 1867, when the first important gold vein was discovered, and prospectors and miners rushed to the area.. The towns of South Pass City, Atlantic City, and Miner's Delight catered to the miners. The district was nearly deserted by 1875, and was worked only intermittently afterward. Total gold production was about 300,000 troy ounces (9,300 kg). In 1962, the district became the site of a major iron mine.[53]

Moraine gold

Several states (e.g., Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania) have placer gold deposits, despite having no hard rock gold deposits. This placer gold is found north of, or near the terminus of, Pleistocene, or earlier, moraines left by Ice Age glaciers that pushed gold-rich dirt down from Canada, where hard rock gold deposits do exist, and which were scoured by glaciers.

Small commercial operations have existed at various times, to mine this gold, with various degrees of limited success. The southernmost limit of these moraines, Pleistocene and older, is approximately at the Ohio River for Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio.[54][55][56] The moraines in Pennsylvania are in the northwestern and northeastern portions of the Commonwealth.[57]

Taxes and royalties

A mineral royalty is a payment to the mineral owner of a portion of the value of an extracted mineral. Royalties are paid on minerals extracted from state land (as specified by state law) and private land (as negotiated with the mineral owner). Much of the gold mined in the western US is extracted from federal land, for which the federal government collects no royalty.

However, a 2009 report by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) characterizes state taxes on mineral production as "functional royalties," in that they take a share of mineral production, including gold production, for the public benefit. State taxes narrowly targeting mineral production include severance taxes, mining license taxes, and extraction excise taxes.[58][59]

Extraction taxes on gold mining in the nine major western gold-mining states (in descending order of gold production) are:

- Nevada – 5% net[60][61]

- Alaska – 7% net[62]

- Utah – 2.6% gross[63]

- Colorado – 2.25% gross[64]

- California – $5 per ounce produced[58]

- Washington – 0.48% gross[58]

- South Dakota – 4% net[65]

- Montana – 1.6% net[58]

- Idaho – 1% gross[58]

In 2015 Nevada and Alaska together accounted for 90.3% of US gold production.[35][8]

See also

References

- A.H. Koschmann and Bergendahl, 1968, Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p. 253.

- A.H. Koschmann and Bergendahl, 1968, Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p. 211.

- Craig, James R; Rimstidt, J.Donald (1998). "Gold production history of the United States". Ore Geology Reviews. 13 (6): 407. Bibcode:1998OGRv...13..407C. doi:10.1016/S0169-1368(98)00009-2.

- Sheaffer, Kristin N. (31 January 2020). "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020" (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 70–71. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Mining review, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p. 28.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.6-8.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.8.

- Athey, Jennifer E.; Werdon, Melanie B.; Twelker, Evan; Henning, Mitch W. (2016). "Alaska's Mineral Industry 2015" (PDF). Fairbanks: Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Survey. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Kinross reports 2019 fourth-quarter and full-year results" (PDF). Toronto, Ontario: Kinross Gold Corporation. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Annual Report 2019" (PDF). Chicago, IL: Coeur Mining, Inc. 19 February 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "2019 Annual Report" (PDF). Coeur d'Alene, ID: Hecla Mining Company. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Maureen G. Johnson, 1972, ''Gold Placer Deposits of Arizona, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1355.

- A. H. Koschmann and M. H. Bergendahl, Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.40-41.

- A. H. Koschmann and M. H. Bergendahl, Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.40.

- http://www.admmr.state.az.us/Publications/ofr07-24.pdf

- William B. Clark (1970) Gold districts of California, California Division of Mines and Geology, Bulletin 193, p.4.

- A.H. Koschmann and M.H. Bergendahl (1968)Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.55-56.

- A.H. Koschmann and M.H. Bergendahl (1968)Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.70-71.

- A.H. Koschmann and M.H. Bergendahl (1968)Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.82-83.

- Quine, Dan (September 2022). "The Yellow Aster gold mine". Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railway Modelling Review (132).

- "First Bucyrus branded MT3700 goes into service at the New Gold Mesquite Mine in California," Mining Engineering, October 2010, p.15.

- "Mesquite Gold Mine". Equinoxgold. Vancouver, BC. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Operations and Projects". Newmont. Newmont Mining Corporation. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Placard at Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park.

- A. H. Koschmann and M. H. Bergendahl, 1968, Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional paper 610, p.119.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.124-125.

- M. H. Bergendahl (1964) Gold, in Mineral and Water Resources of Idaho, Idaho Bureau of Mines and Geology, Special Report No. 1, p.93-101.

- V. S. Gillerman and others, Idaho, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p.83.

- Emery T. Cleaves (1964) Mineral resources of Montgomery and Howard Counties, in Howard and Montgomery Counties, Maryland Geological Survey, p.264-266.

- Ropes Mine, Ishpeming, Marquette Co., Michigan, USA, mindat.org, 2010, accessed 2010-10-12.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.141-142.

- A. H. Koschman and M. H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.143.

- Edwin W. Tooker, 1990, "Gold in the Butte district, Montana," in Gold in Porphyry Copper Systems, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1857-E, p.E19

- R. McCullough, Montana, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p.95.

- Perry, Rick; Visher, Mike (2019). "Major mines of Nevada 2018: Mineral industries in Nevada's economy" (pdf). Nevada Division of Minerals. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology. p. 24. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Gold mine production". Goldhub. London: World Gold Council. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Fayette Jones (1905) New Mexico Mines and Minerals, reprinted as Old Gold Mines and Ghost Camps of New Mexico, Fort Davis, Tex.: Frontier Book Co., p.21-23.

- Harley, George Townsend, The Geology and Ore Deposits of Sierra County, New Mexico, New Mexico State Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Bulletin 10, 1934, pp 139-140

- "Annual Report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(D) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the Fiscal Year ended December 31, 2018" (PDF). Freeport-McMoRan Inc. 15 February 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.212.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.231.

- US Geological Survey: Carolina Slate Belt Gold Deposits

- Jeffrey C. Wynn and Robert W. Luce, Geophysical methods as mapping tools in a strata-bound gold deposit: Haile mine, Carolina slate belt, Economic Geology, March April 1984, p.383-388.

- W.H. Spence and others, Origin of the gold mineralization at the Haile mine, Lancaster County, South Carolina, Mining Engineering, January 1980, p.70-73.

- "OceanGold pours first gold at Haile mine in South Carolina," Engineering & Mining Journal, Feb. 2017, p.4.

- Brewer Gold Mine NPL Site Summary – Land Cleanup and Wastes | Region 4 | US EPA

- "2016 Fourth quarter and full-year earnings" (PDF). Coeur Mining. 9 February 2017. p. 21. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.240.

- Edgar B. Heylman, Gold in Texas, International California Mining Journal, October 2001.

- Els, Frik (11 November 2014). "Bingham Canyon rebuilds after landslide". MINING.com. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- R.L. Bon and K.A. Krahulec, Utah, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p.116.

- A.H. Koschman and M.H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.254-255.

- Richard W.Bayley (1969) Ore deposits of the Atlantic City District, Fremont County, Wyoming, in Ore Deposits of the United States, 1933-1967, v.1, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.589-604.

- J.E. Lamar, Gold and Diamond Possibilities in Illinois, June 1968, http://www.isgs.uiuc.edu/education/pdf-files/gold-poss.pdf Archived 2011-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Geofacts #9, Gold in Ohio, November 1995, http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/Portals/10/pdf/GeoFacts/geof09.pdf Archived 2012-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Glacial Map of Ohio http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/portals/10/pdf/glacial.pdf Archived 2012-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Glacial Map of Pennsylvania http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/topogeo/maps/map59.pdf

- Nazzaro, Robin M. (2010). Hardrock Mining: Information on State Royalties and the Number of Abandoned Mine Sites and Hazards: Congressional Testimony. Collingdale, PA: Diane Publishing. pp. 9–27. ISBN 978-1437919134. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Gold production by state" (PDF). National Mining Association. Spokane, WA. 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Understanding Nevada's Net Proceeds of Minerals Tax (PDF). Carson City: NevadaTaxpayers Association. 2008.

- "2013-2014 Net Proceeds of Minerals Bulletin" (pdf). Nevada Department of Taxation. Carson City: Division of Local Government Services. 8 July 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- "Mining License Tax". Alaska Department of Revenue – Tax Division. State of Alaska. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Severance Tax on Oil, Gas, and Mining". Utah Code. Salt Lake City: Utah State Legislature. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "House Bill 99-1249". General Assembly of the State of Colorado. Denver. 1999. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Stinson, Thomas F. (1977). State taxation of mineral deposits and production, Volume 1. United States. Environmental Protection Agency. p. 40. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

External links

- California

- California Department of Mines and Geology: Map of Historic Gold Mines

- California Department of Mines and Geology: Map of California Active Gold Mines 2000-2001

- California Department of Mines and Geology: The Discovery of Gold in California

- Maryland

- Texas

- Utah

- National

.svg.png.webp)