Gorakhnath

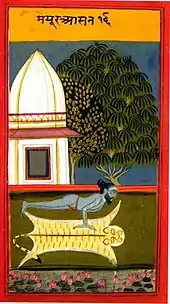

Gorakhnath (also known as Goraksanath,[3] c. early 11th century) was a Hindu yogi, saint who was the influential founder of the Nath Hindu monastic movement in India[4] He is considered one of the two notable disciples of Matsyendranath. His followers are called yogis, Gorakhnathi, Darshani or Kanphata.[5]

Gorakhnath | |

|---|---|

Statue of Gorakhnath performing yogic meditation in lotus position at Laxmangarh temple, India | |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Sect | Nath Sampradaya (sect of Shaivism) |

| Known for | Hatha yoga,[1][2] Nath Yogi organisation, Guru, Gorakhpur |

| Founder of | Nath monasteries and temples |

| Philosophy | Hatha yoga |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Matsyendranath |

| Honors | Mahayogi |

He was one of nine saints also known as Navnath and is widely popular in Maharashtra, India.[6] Hagiographies describe him as more than a human teacher and someone outside the laws of time who appeared on earth in different ages.[7] Historians state Gorakhnath lived sometime during the first half of the 2nd millennium CE, but they disagree in which century. Estimates based on archaeology and text range from Briggs' 11th to 12th century[7] to Grierson's estimate of the 14th century.[8]

Gorakhnath is considered a Maha-yogi (or great yogi) in the Hindu tradition.[9] He did not emphasise a specific metaphysical theory or a particular Truth, but emphasised that the search for Truth and the spiritual life is a valuable and normal goal of man.[9] Gorakhnath championed Yoga, spiritual discipline and an ethical life of self-determination as a means to reaching samadhi and one's own spiritual truths.[9]

Gorakhnath, his ideas and yogis have been highly popular in rural India, with monasteries and temples dedicated to him found in many states of India, particularly in the eponymous city of Gorakhpur.[10][11]

Biography

Historian accounts

_02.jpg.webp)

Historians vary in their estimate on when Gorakhnath lived. Estimates based on archaeology and text range from Briggs' 11th to 12th century[7] to Baba Farid documents and Jnanesvari manuscripts leading Abbott to connect Gorakhnath to the 13th century,[12] to Grierson, who, relying on evidence discovered in Gujarat, suggests the 14th century.[12] His influence is found in the numerous references to him in the poetry of Kabir and of Guru Nanak of Sikhism, which describe him as a very powerful leader with a large following, thereby suggesting he likely lived around the time these spiritual leaders lived in India.[13]

Historical texts imply that Gorakhnath was originally a Buddhist in a region influenced by Shaivism, and he converted to Hinduism championing Shiva and Yoga.[14] Gorakhnath led a life as a passionate exponent of ideas of Kumarila and Adi Shankara that championed the Yogic and Advaita Vedanta interpretation of the Upanishads.[15] Gorakhnath considered the controversy between dualism and nondualism spiritual theories in medieval India as useless from practice point of view, he emphasised that the choice is of the yogi, that the spiritual discipline and practice by either path leads to "perfectly illumined samadhi state of the individual phenomenal consciousness", states Banerjea.[16]

Hagiographic accounts

The hagiography on Gorakhnath describe him to have appeared on earth several times.[7] The legends do not provide a time or place where he was born, and consider him to be superhuman.[17] North Indian hagiographies suggest he originated from northwest India (Punjab, with some mentioning Peshawar).[17] Other hagiographies on Gorakhnath in Bengal and Bihar suggest he originated from eastern region of India (Assam).[17]

These hagiographies are inconsistent, and offer varying records of the spiritual descent of Gorakhnath. All name Adinath and Matsyendranath as two teachers preceding him in the succession. Though one account lists five gurus preceding Adinath and another lists six teachers between Matsyendranath and Gorakhnath, current tradition has Adinath identified with Lord Shiva as the direct teacher of Matsyendranath, who was himself the direct teacher of Gorakhnath.[18]

Nath Sampradaya

The Nath tradition states that its traditions existed before Gorakhnath, but the movement's greatest expansion happened under the guidance and inspiration of Gorakhnath. He produced a number of writings and even today is considered the greatest of the Naths. It has been purported that Gorakhnath wrote the first books on Laya yoga. In India there are many caves, many with temples built over them, where it is said that Gorakhnath spent time in meditation. According to Bhagawan Nityananda, the samadhi shrine (tomb) of Gorakhnath is at Nath Mandir near the Vajreshwari temple about one kilometre from Ganeshpuri, Maharashtra, India.[19] According to legends Gorakhnath and Matsyendranath did penance in Kadri Temple at Mangalore, Karnataka. They are also instrumental in laying Shivlingam at Kadri and Dharmasthala.

The temple of Gorakhnath is also situated on hill called Garbhagiri near Vambori, Tal Rahuri; Dist Ahmednagar. There is also a famous temple of Gorakhnath in the state of Odisha.

Gorakhnath Math

The Gorakhnath Math is a monastery of the Nath monastic group named after the medieval saint, Gorakhnath (c. 11th century), of the Nath sampradaya. The math and town of Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh is named after him. The monastery and the temple perform various cultural and social activities and serve as the cultural hub of the city. The monastery also publishes texts on the philosophy of Gorakhnath.[20]

The math was established in the late 18th century with simultaneous grants of land to muslim holy man, Baba Roshan Ali Shah and Baba Gorakhnath by the Asaf-ud Daula, the Nawab of Awadh.The tomb of Roshan Ali and the Gorakhnath temple on the opposite sides of the city form the core of the identity of Gorakhpur.The math is situated in a Muslim majority area, and until 1980s the Math asyncretic identity with devotees and visitors from diverse communal background.[21]

Influence

Hatha yoga

Some scholars associate the origins of Hatha yoga with the Nath yogis, in particular Gorakhnath and his guru Matsyendranath.[2][22][23] According to British indologist James Mallinson, this association is false.[22] In his view, the origins of hatha yoga should be associated with the Dashanami Sampradaya of Advaita Vedanta[24] (Hinduism), the mystical figure of Dattatreya,[25] and the Rāmānandīs.[26]

While the origins of Hatha yoga are disputed, according to Guy Beck, a professor of Religious Studies known for his studies on Yoga and music, "the connections between Goraknath, the Kanphatas and Hatha yoga are beyond question".[1]

Langars (community kitchens)

According to Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair, a professor in Asian languages and cultures, the Gorakhnath orders were operating free community kitchens in Punjab before Guru Nanak founded Sikhism.[27][28] Gorakhnath shrines have continued to operate a langar and provide a free meal to pilgrims who visit.[29]

Nepal

The Gurkhas of Nepal take their name from this saint.[30] Gorkha, a historical district of Nepal, is named after him.

There is a cave with his paduka (footprints) and an idol of him.[31] Every year on the day of Baisakh Purnima there is a great celebration in Gorkha at his cave, called Rot Mahotsav; it has been celebrated for the last seven hundred years.[32][33]

A legend asserts, state William Northey and John Morris, that a disciple of Machendra by name Gorakhnath, once visited Nepal and retired to a little hill near Deo Patan. There he meditated in an unmovable state for twelve years. The locals built a temple in his honour there, and it has since been remembered with.[34]

Siddhar tradition

In the Siddhar tradition of Tamil Nadu, Gorakhnath is one of the 18 esteemed Siddhars of yore, and is better known as Korakkar.[35] Siddhar Agastya and Siddhar Bhogar were his gurus. There is a temple in Vadukku Poigainallur, Nagapattinam, Tamil Nadu which specifically houses his Jeeva Samadhi.[36] According to one account, he spent much of his youth in the Velliangiri Mountains, Coimbatore.

There are various other shrines in respect of Korakkar; located in Perur, Thiruchendur and Trincomalee, to name a few. Korakkar Caves are found in both Sathuragiri and the Kolli Hills, where he is noted to have practised his sadhana. Like his colleagues, the 18 Siddhars, Korakkar also penned much cryptic Tamil poetry pertaining to Medicine, Philosophy and Alchemy. He was one of the first to use Cannabis in his medicinal preparations for certain ailments, and as such the plant has another less well known name, Korakkar Mooligai (Korakkar's Herb).[37]

West Bengal – Assam – Tripura - Bangladesh

The Bengali Hindu community in Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam and the country Bangladesh have a sizeable number of people belonging to the Nath Sampradaya, variously named as Nath or Yogi Nath, who have taken the name from Gorakhnath.[38][39] They were marginalised in Medieval Bengal.[40]

Works

Romola Butalia, an Indian writer of Yoga history, lists the works attributed to Gorakhnath as including the Gorakṣaśataka, Goraksha Samhita, Goraksha Gita, Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati, Yoga Martanda, Yoga Siddhanta Paddhati, Yogabīja, Yogacintamani.

Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati

The Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati is a Hatha Yoga Sanskrit text attributed to Gorakhnath by the Nath tradition. According to Feuerstein (1991: p. 105), it is "one of the earliest hatha yoga scriptures, the Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati, contains many verses that describe the avadhuta" (liberated) yogi.[41][42]

The Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati text is based on an advaita (nonduality) framework, where the yogi sees "himself in all beings, and all in himself" including the identity of the individual soul (Atman) with the universal (Brahman).[30] This idea appears in the text in various forms, such as the following:

The four varna (castes) are perceived to be located in the nature of the individual, i.e. Brahmana in sadacara (righteous conduct), Ksatriya in saurya (valor and courage), Vaisya in vyavasaya (business), and Sudra in seva (service). A yogin experiences all men and women of all races and castes within himself. Therefore he has no hatred for anybody. He has love for every being.

— Gorakhnath, Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati III.6-8 (Translator: D Shastri)[43]

See also

References

- Guy L. Beck 1995, pp. 102–103.

- "Hatha Yoga". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- Bruce M. Sullivan (1997). Historical Dictionary of Hinduism. Scarecrow Press. pp. 96, 149. ISBN 978-0-8108-3327-2.

- Briggs 1938, p. 228.

- Briggs 1938, p. 1.

- Briggs 1938, pp. 228–250.

- Briggs 1938, p. 249.

- Briggs 1938, pp. 228–230.

- Akshaya Kumar Banerjea 1983, pp. 23–25.

- White, David Gordon (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press, pp. 7–8

- David N. Lorenzen and Adrián Muñoz (2012), Yogi Heroes and Poets: Histories and Legends of the Naths, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-1438438900, pp. x–xi

- Briggs 1938, pp. 230, 242–243.

- Briggs 1938, pp. 236–242.

- Briggs 1938, pp. 229, 233–235.

- Akshaya Kumar Banerjea 1983, pp. xli, 303–307.

- Akshaya Kumar Banerjea 1983, pp. xli, 307–312.

- Briggs 1938, p. 229.

- Briggs 1938, pp. 229–231.

- "Discipleship". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- Akshaya Kumar Banerjea 1983, p. .

- Chaturvedi, Shashank (July 2017). "Khichdi Mela in Gorakhnath Math : Symbols, Ideas and Motivations". Society and Culture in South Asia. 3 (2): 135–156. doi:10.1177/2393861717706296. ISSN 2393-8617. S2CID 157212381.

- James Mallinson (2014). "The Yogīs' Latest Trick". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. 24: 165–180. doi:10.1017/S1356186313000734. S2CID 161393103.

That these Nāth Yogīs were the originators and foremost exponents of haṭhayoga is a given of all historical studies of yoga. But these Yogīs were in fact the willing and complicit beneficiaries of the semantic confusion which has caught out White and many other scholars

- Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, p. 140.

- James Mallinson 2011, pp. 331–332 with footnote 22.

- James Mallinson 2012, pp. 26–27.

- James Mallinson 2012, pp. 26–27, Quote: "Thee key practices of hathayoga—including complex, non-seated āsanas [...] whose first descriptions are found in Pāñcarātrika sources—originated among the forerunners of the Dasnāmīs and Rāmānandīs.".

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4411-1708-3.

- "Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair: Bloomsbury Publishing (US)". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- Geaves, Ron (2007). Saivism in the Diaspora: Contemporary Forms of Skanda Worship. Equinox Pub. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-84553-234-5.

- Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, pp. 440–441.

- "Gorkha: The Historical Landmark of Nepal". Nepal Sanctuary Treks. 10 September 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Gauron, Julianne. "Nepal's Rot Festival at Gorhka's Durbar Palace". SNOW ON THE ROAD.

- "Brief Introduction". District Coordination Committee Office Gorkha.

- Northey, W. B.; Morris, C. J. (2001). The Gurkhas: Their Manners, Customs, and Country. Asian Educational Services.

- R. N. Hema (December 2019). Biography of the 18 Siddhars (Thesis). National Institute of Siddha.

- "18 Siddhars". www.satsang-darshan.com. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- R. N. Hema (December 2019). Biography of the 18 Siddhars (Thesis). National Institute of Siddha.

- Briggs, George Weston (1989). Gorakhnāth and the Kānphaṭa Yogīs. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 243. ISBN 978-81-208-0564-4.

- Bhaṭṭācārya, Āśutosha (1978). Folklore of Bengal. National Book Trust, India. p. 124,132.

- Debnath, Kunal (June 2023). "The Naths of Bengal and Their Marginalisation During the Early Medieval Period". Studies in People's History. 10 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1177/23484489231157499. ISSN 2348-4489. S2CID 259185097.

- Feuerstein, Georg (1991). 'Holy Madness'. In Yoga Journal May/June 1991. With calligraphy by Robin Spaan. Source: p. 105 (accessed: 29 February 2011)

- Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, p. 453.

- Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, p. 440.

Sources

- Akshaya Kumar Banerjea (1983). Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120805347.

- Briggs, G.W. (1938). Gorakhnath and the Kanphata Yogis (6th ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120805644. (2009 Reprint)

- Guy L. Beck (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1261-1.

- Gerald James Larson; Ram Shankar Bhattacharya; Karl H. Potter (2008). Yoga: India's Philosophy of Meditation. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3349-4.

- James Mallinson (2011). "Siddhi and Mahāsiddhi". In Knut Jacobsen (ed.). Early Haṭhayoga in Yoga Powers: Extraordinary Capacities Attained Through Meditation and Concentration. Leiden: Brill Academic. pp. 327–344.

- James Mallinson (March 2012). "Yoga and Yogis". Namarupa. 3 (15): 1–27.

- James Mallinson (2014). "Haṭhayoga's Philosophy: A Fortuitous Union of Non-Dualities". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 42 (1): 225–247. doi:10.1007/s10781-013-9217-0. S2CID 170326576.

Further reading

- Adityanath (2005). Gorakhnath. Retrieved 7 March 2006.

- Romola Butalia (2003). In the Presence of the Masters. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1947-0

- Dhallapiccola, Anna. Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend. ISBN 0-500-51088-1

- Gordan Djurdjevic & Shukdev Singh, Sayings of Gorakhnāth: Annotated Translation of the Gorakh Bānī, ISBN 9780199977673, Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Mahendranath, Shri Gurudev. Notes on Pagan India. Retrieved 7 March 2006.

External links

- Works by or about Gorakhnath at Internet Archive

- Bibliography of Goraksanatha's works, Item 666, Karl Potter, University of Washington