Roots of Yoga

Roots of Yoga is a 2017 book of commentary and translations from over 100 ancient and medieval yoga texts, mainly written in Sanskrit but including several other languages, many not previously published, about the origins of yoga including practices such as āsana, mantra, and meditation, by the scholar-practitioners James Mallinson and Mark Singleton.

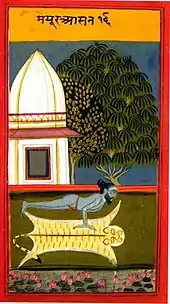

On the book's cover, a yogi practises tapkāra āsana, the ascetic's pose. | |

| Author | James Mallinson Mark Singleton |

|---|---|

| Country | London, UK |

| Series | Penguin Classics |

| Subject | History of yoga |

| Genre | Anthology |

| Publisher | Penguin Books |

Publication date | 2017 |

| Pages | 540 |

| OCLC | 928480104 |

Critics unanimously welcomed the book, noting that it was surprising given yoga's popularity that many of its key texts had never before been translated. They described the book as scholarly, unprecedented, and admirably unbiased, making available a wealth of material in far more accessible form than ever before, and revealing yoga to consist of many strands rather than having a single definite philosophy and interpretation.

Book

Publication

Roots of Yoga was published by Penguin Classics in 2017 as a paperback volume of 540 pages; it was not preceded by a hardback edition.[1] The book has no illustrations other than the cover image.[2] In 2019, an Italian translation was published by Ubaldini in Rome in its Civiltà dell'Oriente ("Civilisations of the Orient") series.[3]

Synopsis

The book is a collection of mostly original translations by the editors of over one hundred yoga texts, mainly from Sanskrit but also including Tibetan, Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Tamil, Pali, Kashmiri, and early forms of Marathi and Hindi.[RY 1]

Its eleven themed chapters cover the nature of yoga itself[RY 2] and the traditional practices, theories, and contexts of yoga. These are the eight limbs of yoga set out in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, which the book calls "the best-known early expression of yoga",[RY 3] and additional topics described in medieval texts, namely:

| The Yamas, from the 4th century Pātañjalayogaśāstra 2.30 |

|---|

| 'The rules are: non-violence, truthfulness, not stealing, sexual continence, and non-acquisitiveness.'[lower-alpha 1] Of these, non-violence is never causing harm in any way to any creature. The other rules and observances are rooted in it.[RY 5] |

| Siddhāsana, from the 15th century Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā 1:35 |

|---|

| Press one heel against the perineum, fix the other foot above the penis and firmly place the chin on the chest. Motionless and with the senses restrained, gaze unwaveringly between the eyebrows. Known as the adept's pose, this bursts open the door to liberation.[RY 6] |

| Meditation, from the 13th century Vivekamārtaṇḍa 151 |

|---|

| If, with the gaze between the eyebrows, the yogi meditates on the self as the unconditioned, quiescent, resplendent Śiva in the skull, he becomes Brahman.[RY 7] |

- preliminaries to yoga practice including ethical rules (yamas and niyamas) and purifications (shatkarmas);[RY 8]

- postures (āsana);[RY 9]

- breath control (prāṇāyāma);[RY 10]

- the subtle body;[RY 11]

- yogic seals (mudrā) to manipulate or trap the subtle body's vital energies such as prana and bindu;[RY 12]

- repeated verbal formulas (mantra);[RY 13]

- withdrawal of the mind from things in the world (pratyāhāra), fixation of the mind through concentration (dhārāṇa), and meditation to develop advanced states (dhyāna);[RY 14]

- the highest cognitive state, the attainment of the union called "yoga" (samādhi);[RY 15]

- special powers (siddhi);[RY 16] and finally

- liberation from suffering (mokṣa).[RY 17]

The editors note that there is at least an apparent paradox in describing these as yoga, as "yoga" is both the entire process and the goal or end-point, samādhi, of that process.[RY 18]

The book has a main introduction summarizing the history of yoga and yoga scholarship,[RY 19] and each chapter has its own shorter contextual introduction and notes.[RY 20] The book provides a variety of helps for the reader such as a timeline of important events from the 1500 BCE Vedas up to the 19th century;[RY 21] tables of the systems of the limbs or "auxiliaries" of yoga, including fourfold, fivefold, sixfold, sevenfold and fifteen-fold systems as well as several eightfold systems including Patanjali's;[RY 22] a glossary;[RY 23] lists of primary and secondary literature;[RY 24] notes;[RY 25] and an index.[RY 26]

Reception

Roots of Yoga was welcomed by its reviewers, both academics and yoga teachers. Among academics, Neil Sims, reviewing Roots of Yoga on the Indian Philosophy Blog, calls the book scholarly, writing that the editors (the yoga scholar-practitioners[4] James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, both of SOAS) "do an admirable job of letting the texts speak for themselves. No hint of partisanship, or even a preferred view, is given." In Sims's view, the book succeeds both on the level of increasing historical understanding among yoga students and teachers, and in contributing to yoga and South Asian scholarship.[5]

The Indologist Alexis Sanderson writes that the anthology's "unprecedented array of sources [...] will be an indispensable companion for all interested in yoga, both scholars and practitioners".[6] Theo Wildcroft, reviewing the book for the Open University blog, writes that the most usual dismissal of yoga scholars is that "as non-practitioners [they] can only have the most superficial of understandings of the practice",[7] noting that Singleton is a practitioner of postural yoga and Mallinson is "much more demonstrably so",[7] having been ordained as a mahant (abbot) during a Kumbh Mela.[8]

Among yoga teachers, Matthew Remski, reviewing the book in Yoga Journal, points to the book's "endlessly diverse sources",[9] which include "new critical translations of over 100 little-known yoga texts dating from 1000 BCE to the 19th century, threaded together with clear and steady-as-she-goes commentary".[9] The translations, he states, "explode the available resources for everyday practitioners" and "drown the notions that yoga is any single thing that anyone has ever agreed upon or that it brings everyone to the same place."[9] Remski proposes that it may "become the top book on every yoga teacher training reading list in the English-speaking world."[9] The yoga teacher Richard Rosen writes that Roots of Yoga is appropriately in Penguin Classics as "this monumental anthology" of some 150 primary Sanskrit sources will in his view become a classic.[4]

Brian Cooper, reviewing the book for the Yoga Alliance, writes that it was astonishing given yoga's popularity that so few of its original texts had been translated. He notes that the authors had deliberately made available over 100 primary sources "of key importance" to grasping yoga's history. Cooper notes that the experience of reading such a collection of excerpts is quite unlike that of browsing a complete text, making the material far more accessible. He calls the book "an incredible resource", illustrating the "vast and complex" corpus of knowledge and practice that is yoga, and showing "that yoga is not a static historical object but a dynamic, intertwining and evolving form."[10]

The indologist Adrián Muñoz, in a review for Estudios de Asia y Africa, writes that the book, based on prolonged research and knowledge of several Indian languages, is intended as a basic and enduring textbook, not limited to the physical aspects of yoga. He describes the introduction as erudite, at once presenting the book's organisation and setting its themes and the texts it uses in context. He comments that one gap is the relatively light coverage of vernacular languages like Braj Bhāṣā. In his view, the book thus gives the impression the "roots" of yoga are mainly literary and in Sanskrit. Muñoz writes that the general reader could feel a bit lost in the technical introductions to the chapters, but he finds the translations reliable and the selections ample and relevant, making the book very useful.[11]

See also

- Yoga Body, Mark Singleton's 2010 book on the origins of global yoga in physical culture

Notes

- Patanjali's text is structured as short pithy sutras (here, in quotes), summarising earlier wisdom, followed by his commentary on the sutras (smaller font).[RY 4]

References

Primary

These indicate the parts of the Roots of Yoga text being discussed.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. xxv1

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 3–45

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. xvi–xvii

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. xi, xvi–xvii

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 81

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 109

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 319

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 46–85

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 86–126

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 127–170

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 171–227

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 228–258

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 259–282

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 283–322

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 323–358

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 359–394

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 395–435

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 46–47

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. ix–xxxviii

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 3, 473–476 for chapter 1, similarly for every other chapter

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. xxxix–xl

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 9–10

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 437–441

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 443–472

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 473–506

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 511–540

Secondary

- ti:Roots of Yoga au:Mallinson Singleton. WorldCat. OCLC 993131293.

- Roots of Yoga. WorldCat. OCLC 1005287729.

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2019). Le radici dello yoga (in Italian). Translated by Marco Passavanti. Ubaldini. p. 477. ISBN 9788834017715.

- Rosen, Richard. "The Roots of Yoga". You and the Mat. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- Sims, Neil (30 December 2017). "Book Review of Roots of Yoga, Translated and Edited by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton". The Indian Philosophy Blog. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Roots of Yoga | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". Penguin Random House. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Wildcroft, Theo. "The launch and reception of Roots of Yoga". Open University. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Sanyal, Amitava (27 February 2013). "Kumbh Mela festival | James Mallinson". BBC.

- Remski, Matthew (12 April 2017). "10 Things We Didn't Know About Yoga Until This New Must-Read Dropped". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Cooper, Brian (17 May 2019). "Roots of Yoga". Yoga Alliance.

- Muñoz, Adrián (2018). "James Mallinson y Mark Singleton (trad., ed. e introd.), Roots of Yoga, Londres, Penguin Books, 2017, 540 pp". Estudios de Asia y Africa (in Spanish). 53 (1 (165)): 225–236.

Sources

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.