Postural yoga in India

Postural yoga began in India as a variant of traditional yoga, which was a mainly meditational practice; it has spread across the world and returned to the Indian subcontinent in different forms. The ancient Yoga Sutras of Patanjali mention yoga postures, asanas, only briefly, as meditation seats. Medieval Haṭha yoga made use of a small number of asanas alongside other techniques such as pranayama, shatkarmas, and mudras, but it was despised and almost extinct by the start of the 20th century. At that time, the revival of postural yoga was at first driven by Indian nationalism. Advocates such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda made yoga acceptable in the 1920s, treating it as a medical subject. From the 1930s, the "father of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya developed a vigorous postural yoga, influenced by gymnastics, with transitions (vinyasas) that allowed one pose to flow into the next.

.JPG.webp)

Krishnamacharya's pupils K. Pattabhi Jois and B. K. S. Iyengar brought yoga to the West and developed it further, founding their own schools and training yoga teachers. Once in the West, yoga quickly became mixed with other activities, becoming less spiritual and more energetic as well as commercial.

Westernized postural yoga returned to India to rejoin the many forms already in the country, transformed by the pizza effect on its round trip. Western yoga tourists, attracted initially by The Beatles' 1968 visit to India, came to study yoga in centres such as Rishikesh and Mysore. From 2015, India, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, held an annual International Day of Yoga, the armed forces and civil service being joined in mass demonstrations by members of the public.

Ancient origins

Yoga's ancient spiritual and philosophical goal was to unite the human spirit with the Divine.[1] It was largely a meditational practice; classical yoga such as is described in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, written around the second century, mentions yoga postures, asanas, only as meditation seats, stating simply that the posture should be easy and comfortable.[2] The Sanskrit word योग yoga means "yoking, joining".[3]

Medieval Haṭha yoga

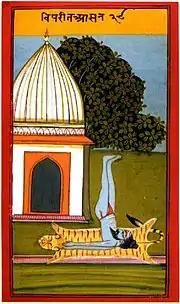

The branch of yoga that makes use of physical postures is Haṭha yoga. The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha means "force", alluding to its use of physical techniques.[5]

Haṭha yoga flourished from c. 1100.[6] It was practised by Nath and other yogins in South Asia.[7] Its performance was solitary and ascetic.[8] All its procedures were secret.[9] Its objectives were to force the vital fluid prana into the central sushumna channel of the subtle body to raise kundalini energy, enabling Samadhi (absorption) and ultimately Moksha (liberation).[10][11] Hatha yoga made use of a small number of asanas, mainly seated; in particular, there very few standing poses before 1900.[10][12] They were practised slowly; positions were often held for long periods.[13] The practice of asanas was a minor preparatory aspect of spiritual work.[7]

Indian practices for independence

By the end of the 19th century, Hatha yoga was almost extinct in India, practised by people on the edge of society, despised by Hindus and the British Raj alike. That changed when Yogendra (starting in 1918) and Kuvalayananda (starting in 1924) taught yoga ostensibly as a means of attaining physical wellbeing, and to study its medical effects, though motivated by a nationalistic desire to show the greatness of Indian culture. They accordingly emphasised the physical practices of Haṭha yoga, the asanas and yoga breathing (pranayama), at the expense of its more esoteric practices such as purifications (shatkarmas), the mudras intended to manipulate the vital forces, and indeed any mention of the subtle body or liberation.[14][15] They were soon followed by the "father of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya at the Mysore Palace. He experimented with many new yoga asanas and transitions between them (vinyasas), creating a dynamic style of postural yoga.[16] Krishnamacharya observed and adjusted each pupil in an individualised approach to teaching, which later became known as viniyoga.[17][18] One factor influencing the popularity of yoga as exercise was Indian nationalism; having strong bodies meant being a strong country which could shake off colonial rule. Another was photography: complex body positions could for the first time be captured in a photograph rather than hard-to-follow words.[19]

Exotic exercise for the Western world

The 20th century saw a series of yoga gurus establish schools of yoga in India, train yoga teachers, and turn themselves into brands known around the world: Krishnamacharya and his pupils K. Pattabhi Jois and B. K. S. Iyengar, and Sivananda among them.[20] Jois founded Ashtanga Yoga, a vigorous vinyasa style, with its headquarters at the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute in Mysore. Iyengar founded Iyengar Yoga, a precise style that emphasises correct alignment, using supports where necessary, based at the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Institute (RIMYI) in Pune.[21] Sivananda and his disciples including Vishnudevananda created Sivananda Yoga, a more spiritual style, based in Rishikesh.[22]

The practice of the medieval seated asanas survived into the 20th century in Calcutta, and was cultivated by Buddha Bose and Bishnu Ghosh.[23][24] Among Ghosh's pupils was Labanya Palit; she published a manual of 40 asanas, Shariram Adyam ("A Healthy Body"), in 1955, admired by the poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore.[25][26] The yoga teacher Bikram Choudhury (born 1944 in Calcutta) claimed falsely to have learnt Hatha Yoga directly from Ghosh; actually he began yoga in 1969, influenced by Ghosh's writings. He emigrated to America in 1971 to found Bikram Yoga.[27][28] Fleeing legal action in America for sexual abuse and other matters, Choudhury returned to India in 2016, opening several yoga studios.[29]

On its arrival in the West, yoga became mixed with a variety of Western activities and concepts, from gymnastics to psychotherapy, Western occultism and New Age religion. Yoga has grown into a widespread and valuable commodity and form of exercise, ranging from gentle to energetic, and practised by millions across the Western world.[19][30]

Return to India

.jpg.webp)

In 1968, the English rock band The Beatles travelled to Rishikesh to take part in a Transcendental Meditation training course at Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's ashram, now derelict and renamed the Beatles Ashram.[31][32] The visit sparked widespread Western interest in Indian spirituality,[31] and has led many Westerners to travel to India hoping to find "authentic"[33] yoga in ashrams in places such as Mysore (for Ashtanga Yoga) and Rishikesh. That movement led in turn to the creation of many yoga schools offering teacher training and promotion of India as a "yoga tourism hub"[34] by the Indian Ministry of Tourism and the Ministry of AYUSH.[33][35][34] Youthful Westerners' sometimes naive spiritual quests to India were gently[36] satirised in the Mindful Yoga instructor Anne Cushman's novel Enlightenment for Idiots.[37][36]

Yoga, transformed by what the Austrian anthropologist and Indologist Agehananda Bharati called "the pizza effect",[19][38] having journeyed across the Atlantic and back, returned with new "flavours and ingredients". It had become sleek, modern, a sign of health and fitness and urban cool; it had in large part lost its close association with Hinduism, and had indeed become almost wholly a form of exercise rather than religion of any kind.[19][39]

In 1992 the anthropologist Sarah Strauss spent 11 months at the Sivananda ashram in Rishikesh, both practising and observing postural yoga in India. The instructors were Indian; the students were American, German, and Indian. She considered that for the Indians, yoga was "embedded in a sense of familial or national belonging", whereas the non-Indians were seeking to "find themselves" in a rapidly globalizing world.[40]

Government-led event

In 2014, the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, persuaded the United Nations General Assembly to create an annual International Day of Yoga. It has been celebrated since 2015 in many countries, but especially enthusiastically in India.[41][42] Modi is a member of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu nationalist volunteer organisation. Critics of Modi have suggested possible motives for the event, from a partisan attempt to make India more Hindu,[43] to the desire to reclaim yoga and have it recognised around the world as "India's cultural property", despite the changes it had undergone.[44] Modi personally led over 35,000 participants on the first Day of Yoga in New Delhi; across India, the Indian Armed Forces ran demonstrations on the decks of warships and high in the Himalayas, while politicians and civil servants from India's large bureaucracy joined events in cities from Chennai to Kolkata and Lucknow.[45]

See also

References

- Monier-Williams, Monier, "Yoga", A Sanskrit Dictionary, 1899.

- Āraṇya, Hariharānanda (1983), Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0873957281, page 228 with footnotes

- White, David Gordon (2011). Yoga in Practice. Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-691-14086-5.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 90.

- Mallinson 2011, p. 770.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 28–29.

- Bühnemann 2007, pp. 20–21.

- Mallinson, James (9 December 2011). "A Response to Mark Singleton's Yoga Body by JamesMallinson". Retrieved 3 July 2019. revised from American Academy of Religions conference, San Francisco, 19 November 2011.

- Singleton 2010, p. 173.

- Singleton 2010, p. 29.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 171 and whole of chapter 5.

- Singleton 2010, p. 161.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 93.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 16–43, 88–141.

- Alter 2004, pp. 73–108.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 208–248.

- Ruiz, Fernando Pagés (May 2001). "Krishnamacharya's Legacy". Yoga Journal (May/June 2001).

- Mohan, A. G. (2010). Krishnamacharya: His Life and Teachings. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 978-1-59030-800-4.

- Singleton, Mark (26 June 2017). "From India with love – how yoga got its stretch back". The Independent.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 152, 175–210.

- "The Pune Institute". Iyengar Yoga (UK). Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Sivananda Lineage and Vision". Inspirasï. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Armstrong, Jerome. "Finding Calcutta Yoga by Jerome Armstrong". Buddha Bose. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Armstrong 2018.

- "The Women of Yoga". Ghosh Yoga. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Rao, Soumya (31 July 2019). "Filling a gap in history: Who were the Indian women who popularised yoga?". Scroll.in.

- Schickel, Erica (25 September 2003). "Body Work". L.A. Weekly.

- Henderson, Julia L. (2018). Bikram. 30for30, season 3, episodes 4&5. ESPN.

- "Disgraced hot yoga guru Bikram Choudhury winds up US business, sets shop in Lonavla". 26 May 2016.

- Jain 2015, pp. 80-81 and whole book.

- Goldberg 2010, pp. 7, 152.

- Parthsarathi, Mona (24 January 2018). "Displays to mark 50 years of Beatles' arrival in India". The Week. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Maddox, Callie Batts (2014). "Studying at the source: Ashtanga yoga tourism and the search for authenticity in Mysore, India". Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change. 13 (4): 330–343. doi:10.1080/14766825.2014.972410. ISSN 1476-6825. S2CID 143449133.

- Singh, Shikha. "Yoga Tourism in India India can be the Wellness Destination for the World". Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Ward, Mariellen (15 March 2012). "How to 'do' a yoga ashram in India".

- Dowdle, Hillari (2008). "Enlightened Fiction" (March 2008). Yoga Journal: 117.

Each character is ripe for a little satire, which makes the novel a fun read, especially if you're in on the joke... Cushman also manages to capture the heart of their teachings, which gives the book another level of meaning.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Douglas, Anna (September 2008). "Enlightenment for Idiots, by Anne Cushman". Inquiring Mind. 25 (1 (Fall 2008)).

- Bharati, Agehananda (1970). "The Hindu Renaissance and its Apologetic Patterns". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 29 (2): 267–287. doi:10.2307/2942625. JSTOR 2942625. S2CID 154591435.

- Farmer, Jared (2012). "Americanasana". Reviews in American History. 40 (1): 145–158. doi:10.1353/rah.2012.0016. S2CID 246283975.

- Strauss 2005, pp. 53–85.

- UN Declared 21 June as International Day of Yoga Archived 9 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "UN declares June 21 as 'International Day of Yoga'". The Times of India. 11 December 2014.

- Associated Press (21 June 2015). "Yoga fans around world take to their mats for first International Yoga Day". The Guardian.

- The Week Staff (7 February 2015). "Does yoga belong to India?". The Week.

- Najar, Nida (21 June 2015). "International Yoga Day Finally Arrives in India, Amid Cheers and Skepticism". The New York Times.

Sources

- Alter, Joseph (2004). Yoga in Modern India : the body between science and philosophy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11874-1. OCLC 53483558.

- Armstrong, Jerome (2018). Calcutta Yoga : Buddha Bose & the yoga family of Bishnu Ghosh and Yogananda. Webstrong. ISBN 978-0692116715.

- Bühnemann, Gudrun (2007). Eighty-Four Asanas in Yoga: A Survey of Traditions. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld. ISBN 978-8124604175.

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga : the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

- Goldberg, Philip (2010). American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation – How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-385-52134-5.

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- Mallinson, James (2011). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al. (eds.). Haṭha Yoga in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 3. Brill Academic. pp. 770–781. ISBN 978-90-04-27128-9.

- Mallinson, James & Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

- Strauss, Sarah (2005). Positioning Yoga: balancing acts across cultures. Berg. ISBN 978-1-85973-739-2. OCLC 290552174.