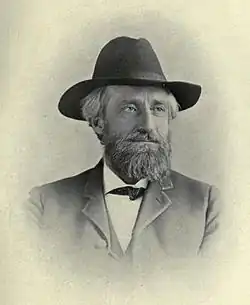

Gordon McKay

Gordon McKay (1821–1903) was an American businessman and philanthropist. An important figure in the mechanization of the shoe industry, his most original idea was to lease his "McKay machines" rather than selling them outright, collecting a small royalty on each pair of footwear made with his equipment. He then secured his market position by cartelization, helping create the United Shoe Machinery Corporation with his potential competitors. Upon his death, after providing for his family and various mistresses, he left the bulk of his estate to Harvard University as an endowment to provide for capable professors to train future engineers. The gift—now over half a billion dollars—was indirectly responsible for Harvard's inability to merge with MIT in the early 20th century.

Gordon McKay | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Born | May 4, 1821 Pittsfield, Massachusetts |

| Died | October 19, 1903 (aged 82) Newport, Rhode Island |

| Burial place | Pittsfield Cemetery |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman, philanthropist |

| Signature | |

Life

McKay was born to a cotton goods manufacturer in Pittsfield, Massachusetts on May 4, 1821.[1][2] Although he studied violin as a boy,[3] he did not graduate high school or attend college but became a self-taught civil engineer and self-made businessman.[1] When his father died in 1833, he went to work as an apprentice in a machine shop at age 12.[1] He briefly worked on a railroad and on the Erie Canal.[3] In 1844, at age 23, he established his own machine shop in Pittsfield.[1] Partnering with J.C. Hoadley as McKay and Hoadley, the firm employed over 100 men before moving in 1852 to Lawrence.[1] While there, he served as treasurer of the Lawrence Machine Shop.[1]

At the time, Lynn and other communities around Boston had become the center of the American shoe industry but they still relied on skilled manual labor organized into elaborate putting-out systems. With modification, Elias Howe and Isaac Singer's early sewing machines were able to stitch shoes' uppers together but could not do the heavy work of attaching the uppers to the soles. Lyman Reed Blake finally worked out how to accomplish this in 1856, receiving his patent in 1858.[1] Realizing how the invention could increase productivity and profits for shoe manufacturers, McKay hired Blake at his company and purchased his patent for $8,000 in cash and an agreement to pay a further $62,000 from future profits.[4] While contesting an earlier agreement Blake had made for less money,[3] the two men then further improved and streamlined the design, with McKay receiving another patent in 1862.[1]

The Civil War had begun in 1861 and the US Army was ordering huge numbers of brogans for its soldiers. McKay filled an order for 25,000 pairs on his own.[3] Rather than sell a few of his stitching machines outright at their full price, though, the McKay Shoe Machinery Company arranged to lease the "McKay machines" to 60 other companies for a low initial fee and royalties on future sales.[1] (The machines included devices that tallied their uses.)[3] The low overhead, increased productivity, ready market, and glowing reports prompted more and more companies to adopt them as well.[1] Blake helped install the machines until retiring in 1874.[1] Ultimately, McKay's company received royalties on billions of pairs of footwear, making $500,000—about 750 kg of gold—a year at the system's height of profitability around 1876.[4] Over 120,000,000 pairs were tallied on McKay's machines in 1895 alone, over half of US production.[4] The legal arrangements were partially handled by Gardiner Greene Hubbard,[5] who later became the first president of the Bell Telephone Company.

The last remaining impediment to mechanized shoe production was lasting, shaping the shoe leather by pulling it tightly over a form. In 1872, McKay attempted to replicate his earlier success by joining with James W. Brooks and Charles W. Glidden to form the McKay Lasting Machine Association and buying out the patents of William Wells's American Lasting Machine Company with the intention of improving them to commercial viability and then leasing the resulting machines.[6] Ultimately, they spent $120,000 on their improvements[7] and, after George Copeland demonstrated a viable lasting machine at the 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair,[6] another $130,000 attempting to sue him for patent infringement.[7] They further absorbed Henry G. Thompson's company, becoming the McKay and Thompson Lasting Machine Association.[6] For his part, Copeland had spent $100,000 on his own efforts and then $170,000 on the litigation.[6] Ultimately McKay won but, seeking the best possible machine, promptly combined with Copeland's firm as the McKay and Copeland Lasting Machine Association in 1881.[6] They were able to market an automated lasting machine but it was limited to heavy work and useless for the pointed toes then in fashion or for women's shoes in thin leather, which still made up the bulk of sales.[7] When the Surinamese-American immigrant Jan Ernst Matzeliger finally solved the problem with his own machine in 1883 and then developed a commercially viable prototype in 1885, McKay swiftly bought out the resulting company, creating the Consolidated McKay Lasting Machine Company.[7] In 1899, this merged with the McKay Shoe Machinery Company, the Goodyear Shoe Machinery Company, and a few smaller manufacturers to create the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, which then dominated American shoemaking for decades.

By this time, living near Harvard Square,[3] McKay had become close friends with Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, the geology professor at Harvard University. Shaler became dean of Harvards's Lawrence Scientific School (now the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences) in 1891. In 1893, McKay placed an initial $4 million in trust for Harvard to provide for its later endowment.[3]

Gordon McKay died at his home in Newport, Rhode Island on October 19, 1903.[1][2] He was buried at Pittsfield Cemetery.[8]

Legacy

McKay built Indian Mound Cottage on Jekyll Island, Georgia, in 1892. After his death, it was sold to William Rockefeller in 1905 and used as his family's winter home during the early 20th century.

In his will, McKay left much of his estate to Harvard University out of his desire to train well-educated engineers and his appreciation for Shaler's investment advice regarding investment in a Montana gold mine.[3] The terms of the will read in part: "I direct that the salaries attached to the professorships maintained from the Endowment be kept liberal, generation after generation, according to the standards of each successive generation, to the end that these professorships may always be attractive to able men and that their effect may be to raise, in some judicious measure, the general scale of compensation for the teachers of the universities."[1] The professorships he endowed are within Harvard's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. The full transfer of the principal was delayed 36 years until 1949, however, because of life trusts he separately established for his second exwife[lower-alpha 1] Minnie Treat, "the prettiest and sweetest young lady the world has produced"[3] and the 36-year-younger daughter of his former housekeeper; for Minnie's two sons allegedly fathered by a Florentine during a period of abstinence in their relationship;[lower-alpha 2] for Minnie's mother and sister; and for 13 other women[lower-alpha 3] of no apparent relation with whom he negotiated life trusts in consideration of their love and affection,[lower-alpha 4] to such an extent that a neighbor complained about him as a "miserible old whore master" filling his house "with loose women under the noses of respectable people".[3] Harvard got its first million in 1909.[4] By the time Harvard received the full amount, the total came to $16 million, the largest single gift received by the university up to that time and still one of the most generous so far when adjusted for inflation.[4] The inability of Harvard to share the bequest with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was an important impediment to the repeated attempts of its president Charles William Eliot to merge the two universities.[1]

Invested by the university, his legacy today has grown to over $500,000,000 and supports 40 professorships in engineering and applied science,[3] one of the most significant monetary contributions to academic salaries. Harvard's Gordon McKay Laboratory for Applied Sciences is named for him. The university also maintains his family mausoleum in gratitude, most recently a 2007 renovation.[1]

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Article by Brian Sullivan in the Berkshire Eagle, Pittsfield MA, September 1, 2011 Thursday September 1, 2011

Gordon McKay

There's nothing like owning a new pair of shoes, unless it's owning the machinery that made those shoes.

McKay Street and the parking garage still carry his name, but that doesn't really reveal all that Gordon McKay did for the city of Pittsfield. Maybe if he had bequeathed upon his death $25 million to Pittsfield instead of Harvard University, from where he did not graduate, he might have a statue on Park Square.

But give McKay credit. He had a vision, followed through on it and earned his millions the old-fashioned way -- he worked for it. He just happened to fall into the right idea at the right time.

Shoes? You bet. He revolutionized the industry.

Born in Pittsfield in 1821, McKay invented a shoe-nailing and "shoe-lasting" machine and made great improvements in a shoe-sewing machine.

McKay, of course, could not make all the shoes for the world by himself. So after locking up a strict patent he leased his equipment and two-stepped his way to the bank on a regular basis.

But McKay was about more than shoes. Before he turned 30 in the year 1850, he realized that the city needed a water supply source and chaired a committee settled on Ashley Lake as that resource.

McKay was a civic-minded force. His other accomplishments -- none of which need to be a backdrop to any of the previously mentioned -- include the following: He was:

The chief of the Fire Department for a time.

In charge of the Berkshire Jubilee celebration in 1844.

A leading member on the committee to build the Berkshire Medical College on South Street.

A member of the committee that in 1851 that built the new First Congregational Church on Park Square, which replaced the old Bullfinch-designed church.

His last known gift to the city of any note was the iron fence (he owned a foundry on McKay St that became E.D. Jones) that surrounded the former House of Mercy when it was located on the corner of Tyler and North streets.

McKay, who for years lived on the corner of South and East Housatonic streets, checked out in grand style. His remains are in a magnificent mausoleum at Pittsfield Cemetery, a structure designed by Mary E. Tillinghart 10 years before McKay's death.

Built of Lee marble, the cathedral walls were first put on exhibit at the 1893 Chicago World Fair before being shipped back to Pittsfield.

McKay may be known now as a downtown street and a parking garage, but obviously he was something a bit more special than that.

Notes

- His first divorce in 1867 had involved "an allegedly libelous pamphlet" to which he had responded with a 30-page account of his wife's abandonment, an extensive list of his gifts to her, and complaints about her mother.[3]

- Each boy was provided $500 a year until their 21st birthday.[3]

- His will initially listed 11 other women, but 6 codicils subsequently removed 5 from the original list and added 7 others.[3]

- An 1897 letter illustrates one arrangement and subsequent disagreement. "My Dear Edith, you asked me to let you know what I could do for you, and you asked me not to write you a terribly cruel note.—I'll try to do the one and avoid the other... You will remember when this commenced I asked you how much you would require a month. And your mother answered (you being present and not dissenting) $300. This was about the undertaking I thought I was engaging in."[3]

References

Citations

Bibliography

- Gordon McKay: Patent Pending: The Founding of Practical Science at Harvard, Cambridge: Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 2013, archived from the original on March 8, 2013.

- Fallon, William P. (October 1935), The Boot and Shoe Manufacturing Industry, Evidence Study, No. 2, Washington: National Recovery Administration Division of Review.

- Jones, R. Victor (November 21, 2001), "Gordon McKay (1821-1903)", R. Victor Jones, Robert L. Wallace Research Professor of Applied Physics..., Cambridge: Harvard University, archived from the original on August 19, 2007.

- Lewis, Harry R. (September–October 2007), "Gordon McKay: Brief Life of an Inventor with a Lasting Harvard Legacy: 1821-1903", Harvard Magazine.

- Morgan, Stuart (May 2020), "The Birth of the Lasting Machine", SATRA Bulletin, Kettering: Shoe and Allied Trade Research Association, p. 38.

- Patten, William; et al. (1926), Pioneering the Telephone in Canada, Montreal: Herald Press.

- Wetherell, Chris T. (January 12, 2019), "The Matzeliger Lasting Machine", Shoe Blog, Carver: CTW Photography.

- "Peaceful End: Gordon McKay Dies at His Newport Home". The Boston Globe. Newport, Rhode Island. October 19, 1903. pp. 1, 8. Retrieved July 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tomb is Small: McKay Mausoleum Must be Altered". The Boston Globe. October 23, 1903. p. 8. Retrieved July 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.