Gothic War (535–554)

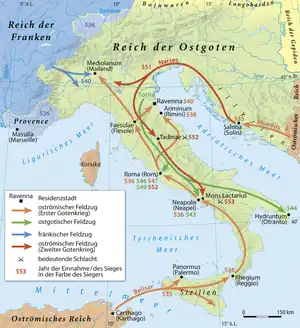

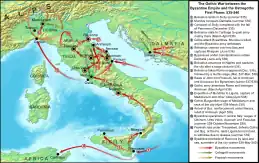

The Gothic War between the Eastern Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Justinian I and the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy took place from 535 to 554 in the Italian Peninsula, Dalmatia, Sardinia, Sicily and Corsica. It was one of the last of the many Gothic Wars against the Roman Empire. The war had its roots in the ambition of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor Justinian I to recover the provinces of the former Western Roman Empire, which the Romans had lost to invading barbarian tribes in the previous century, during the Migration Period.

| Gothic War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Justinian's Renovatio Imperii | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Eastern Roman Empire Huns Heruli Sclaveni Lombards |

Ostrogoths Franks Alamanni Burgundians Visigoths | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Justinian Belisarius Calonymus Mundus † John Narses Bessas Germanus Liberius Conon Artabazes Constantinianus Vitalius Cyprian Bochas Chalazar Odolgan Uldach |

Theodahad Vitiges Ildibad Eraric Totila † Teia † Uraias Uligisalus Asinarius Indulf Scipuar Gibal Butilinus | ||||||||

The war followed the Eastern Roman reconquest of the province of Africa from the Vandals. Historians commonly divide the war into two phases:

- From 535 to 540: ending with the fall of the Ostrogothic capital Ravenna and the apparent reconquest of Italy by the Byzantines.

- From 540/541 to 553: a Gothic revival under Totila, suppressed only after a long struggle by the Byzantine general Narses, who also repelled an invasion in 554 by the Franks and Alamanni.

In 554, Justinian promulgated the Pragmatic sanction which prescribed Italy's new government. Several cities in northern Italy held out against the East Romans until 562. By the end of the war, Italy had been devastated and depopulated. It was seen as a Pyrrhic victory for the East Romans, who found themselves incapable of resisting an invasion by the Lombards in 568, which resulted in Constantinople permanently losing control over large parts of the Italian Peninsula.

Background

Italy under the Goths

In 476 Odoacer deposed Emperor Romulus Augustulus and declared himself rex Italiae (King of Italy), resulting in the final dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in Italy. Although Odoacer recognised the nominal suzerainty of the Eastern Emperor, Zeno, his independent policies and increasing strength made him a threat in the eyes of Constantinople. To provide a buffer, the Ostrogoths, under their leader, Theodoric the Great, were settled as foederati (allies) of the Empire in the western Balkans, but unrest continued. Zeno sent the Ostrogoths to Italy as the representatives of the Empire to remove Odoacer. Theodoric and the Goths defeated Odoacer and Italy came under Gothic rule. In the arrangement between Theodoric and Zeno, and his successor Anastasius, the land and its people were regarded as part of the Empire, with Theodoric a viceroy and head of the army (magister militum).[1] This arrangement was scrupulously observed by Theodoric; there was continuity in civil administration, which was staffed exclusively by Romans, and legislation remained the preserve of the Emperor.[2] The army, on the other hand, was exclusively Gothic, under the authority of their chiefs and courts.[3] The peoples were also divided by religion: the Romans were Chalcedonian Christian, while the Goths were Arian Christians. Unlike the Vandals or the early Visigoths the Goths practised considerable religious tolerance.[4] The dual system worked under the capable leadership of Theodoric, who conciliated the Roman aristocracy, but the system began to break down during his later years and collapsed under his heirs.[5]

With the ascension of Emperor Justin I, the end of the Acacian schism between the Eastern and Western Churches, and the return of ecclesiastical unity within the East, several members of the Italian senatorial aristocracy began to favour closer ties to Constantinople to balance Gothic power. The deposition and execution of the distinguished magister officiorum Boethius and his father-in-law in 524 was part of the slow estrangement of their caste from the Gothic regime. Theodoric was succeeded by his 10-year-old grandson Athalaric in August 526, with his mother, Amalasuntha, as regent; she had received a Roman education and began a rapprochement with the Senate and the Empire. This conciliation and Athalaric's Roman education displeased Gothic magnates, who plotted against her. Amalasuntha had three of the leading conspirators killed and wrote to the new Emperor, Justinian I, asking for sanctuary if she was deposed. Amalasuntha remained in Italy.[6]

Belisarius

.jpg.webp)

In 533, using a dynastic dispute as a pretext, Justinian had sent his most talented general, Belisarius, to recover the North African provinces held by the Vandals. The Vandalic War produced an unexpectedly swift and decisive victory for the Byzantine Empire and encouraged Justinian in his ambition to recover the rest of the lost western provinces. As Regent, Amalasuntha had allowed the Byzantine fleet to use the harbours of Sicily, which belonged to the Ostrogothic Kingdom. After her son's death in 534, Amalasuntha offered the kingship to her cousin Theodahad; Theodahad accepted, but had her arrested and, in early 535, killed.[6] Through his agents, Justinian tried to save Amalasuntha's life but to no avail and her death gave him a casus belli to go to war with the Goths. Procopius wrote that "as soon as he learned what had happened to Amalasuntha, being in the ninth year of his reign, he entered upon war".[7][8]

Belisarius was appointed commander in chief (stratēgos autokratōr) for the expedition against Italy with 7,500 men. Mundus, the magister militum per Illyricum, was ordered to occupy the Gothic province of Dalmatia. The forces made available to Belisarius were small, especially when compared with the much larger army he had fielded against the Vandals, an enemy much weaker than the Ostrogoths. The preparations for the operation were carried out in secret, while Justinian tried to secure the neutrality of the Franks by gifts of gold.[9]

First Byzantine campaign, 535–540

Conquest of Sicily and Dalmatia

Belisarius landed at Sicily, between Roman Africa and Italy, whose population was well disposed toward the Empire. The island was quickly captured, with the only determined resistance, at Panormus (Palermo), overcome by late December. Belisarius prepared to cross to Italy and Theodahad sent envoys to Justinian, proposing at first to cede Sicily and recognise his overlordship but later to cede all of Italy.[10][11]

In March 536 Mundus overran Dalmatia and captured its capital, Salona, but a large Gothic army arrived and Mundus' son Mauricius died in a skirmish. Mundus inflicted a heavy defeat on the Goths but was himself mortally wounded in the pursuit. The Roman army withdrew and, except for Salona, Dalmatia was abandoned to the Goths. Encouraged, Theodahad imprisoned the Byzantine ambassadors. Justinian sent a new magister militum per Illyricum, Constantinianus, to recover Dalmatia and ordered Belisarius to cross into Italy. Constantinianus accomplished his task speedily. The Gothic general, Gripas, abandoned Salona, which he had only recently occupied, because of the ruined state of its fortifications and the pro-Roman stance of its citizens, withdrawing to the north. Constantinianus occupied the city and rebuilt the walls. Seven days later the Gothic army departed for Italy and by late June the whole of Dalmatia was in Roman hands.[12][13]

First siege of Rome

In the late spring of 536 Belisarius crossed into Italy, where he captured Rhegium and made his way north. Neapolis (in Modern English: Naples) was besieged for three weeks before the Imperial troops forced their way in during November. The largely barbarian Roman army sacked the city. Belisarius moved north to Rome, which in view of the fate of Neapolis, put up no resistance; Belisarius entered unopposed in December. The rapidity of the Byzantine advance took the Goths by surprise and the inactivity of Theodahad enraged them. After the fall of Neapolis he was deposed and replaced by Vitiges. He left Rome for Ravenna, where he married Amalasuntha's daughter Matasuntha and began rallying his forces against the invasion. Vitiges led a large force against Rome, where Belisarius, who did not have enough troops to face the Goths in the open field, had remained. The subsequent siege of Rome, the first of three in the Gothic War, lasted from March 537 to March 538. There were sallies, minor engagements and several large actions but after 1,600 Huns and Slavs arrived from Constantinople in April 537 and 5,000 men in November, the Byzantines took the offensive and their cavalry captured several towns in the Goths' rear. The imperial navy cut off the Goths from seaborne supplies, worsening their supply difficulties, and threatened Gothic civilians. The fall of Ariminum, modern Rimini, close to Ravenna, forced Vitiges to abandon the siege and withdraw.[15][16][17]

Siege of Ariminum

As Vitiges marched to the northeast, he strengthened the garrisons of towns and forts along the way to secure his rear and then turned towards Ariminum. The Roman force of 2,000 horsemen occupying it comprised some of Belisarius' finest cavalry; Belisarius decided to replace them with an infantry garrison.[18] Their commander, John, refused to obey orders and remained at Ariminum. Shortly after the Goths arrived, an assault failed, but the city had few supplies with which to stand a siege.[19][20] A new force of 2,000 Herul foederati, under the Armenian eunuch Narses, arrived at Picenum.[21] Belisarius met Narses, who advocated a relief expedition to Ariminum, while Belisarius favoured a more cautious approach. The arrival of a letter from John, which illustrated the immediate danger of the city's fall, resolved the issue in favour of Narses.[22] Belisarius divided his army into three, a seaborne force under his capable and trusted lieutenant Ildiger, another under the equally experienced Martin which was to arrive from the south, and the main force under him and Narses, which was to arrive from the northwest. Vitiges learned of their approach and, faced with the prospect of being surrounded by superior forces, hurriedly withdrew to Ravenna.[23]

The bloodless victory at Ariminum strengthened Narses against Belisarius, with many Roman generals, including John, turning their allegiance to him. In the council after the relief of Ariminum, Belisarius was in favour of reducing the strong Gothic garrison of Auximum, modern Osimo, in their rear and relieving the siege of Mediolanum; Narses favoured a less concentrated effort, including a campaign in Aemilia.[24] Belisarius did not allow matters to fester and marched with Narses and John against Urbinum. The two armies encamped separately and shortly afterwards, Narses, convinced that the town was unassailable and well supplied, broke camp and departed for Ariminum. From there he sent John to Aemilia, which was quickly subdued. Aided by the fortunate drying up of Urbinum's only water spring, the town fell to Belisarius soon after.[25]

Mediolanum

In April 538 Belisarius, petitioned by representatives from Mediolanum (Milan), the second most populous and wealthy city in Italy after Rome, had sent a force of 1,000 men under Mundilas to the city. This force secured the city and most of Liguria, except Ticinum (Pavia), with ease. Vitiges called upon the Franks for help and a force of 10,000 Burgundians unexpectedly crossed the Alps. Combining with the Goths under Uraias they laid siege to the city. Mediolanum was ill-provisioned and under-garrisoned; the already small Roman force had been dispersed to garrison the neighbouring cities and forts.[26] A relief force was dispatched by Belisarius but its commanders, Martin and Uliaris, did not make any effort to help the besieged city. Instead, they asked for further reinforcements by the forces of John and the magister militum per Illyricum Justin, which were operating in the nearby province of Aemilia.[27]

Dissension in the Roman chain of command exacerbated the situation, as John and Justin refused to move without orders from Narses. John fell ill and the preparations were halted. The delays proved fatal for the city, which, after many months of siege, was close to starvation. The Goths offered Mundilas a guarantee that the lives of his soldiers would be spared if he surrendered the city but no guarantee was offered for the civilians and he refused. By the end of March 539, his starving soldiers forced him to accept the terms. The Roman garrison was spared but the inhabitants were subjected to a massacre and the city was razed.[28][Note 1]

Frankish invasion

After this disaster Narses was recalled and Belisarius confirmed as supreme commander with authority throughout Italy. Vitiges sent envoys to the Persian court, hoping to persuade Khosrow I to reopen hostilities with the Byzantines to force Justinian to concentrate the majority of his forces, including Belisarius, in the east and allow the Goths to recover.[29] Belisarius resolved to conclude the war by taking Ravenna but had to deal with the Gothic strongholds of Auximum and Faesulae (Fiesole) first.[30] While Martin and John hindered the Gothic army under Uraias, which was attempting to cross the River Po, a part of the army under Justin besieged Faesulae and Belisarius undertook the siege of Auximum. During the sieges, a large Frankish army under King Theudebert I crossed the Alps and came upon the Goths and the Byzantines encamped on the two banks of the Po. They attacked the Goths who, thinking they had come as allies, were swiftly routed. The equally astonished Byzantines also gave battle, were defeated and withdrew southwards into Tuscany. The Frankish invasion was defeated by an outbreak of dysentery, which caused great losses and forced the Franks to withdraw. Belisarius concentrated on the besieged cities, and both garrisons were forced by starvation to capitulate in October or November 539.[31]

Capture of Ravenna

.jpg.webp)

Troops from Dalmatia reinforced Belisarius and he moved against Ravenna. Detachments moved north of the Po and the imperial fleet patrolled the Adriatic, cutting the city off from supplies. Inside the Gothic capital, Vitiges received a Frankish embassy looking for an alliance but after the events of the previous summer no trust was placed in Frankish offers. Soon afterwards an embassy came from Constantinople, bearing surprisingly lenient terms from Justinian. Anxious to finish the war and concentrate against the impending Persian war, the Emperor offered a partition of Italy; the lands south of the Po would be retained by the Empire, those north of the river by the Goths. The Goths readily accepted the terms but Belisarius, judging this to be a betrayal of all he had striven to achieve, refused to sign, even though his generals disagreed with him.[32]

Disheartened, the Goths offered to make Belisarius, whom they respected, the western emperor. Belisarius had no intention of accepting the role but saw how he could use this situation to his advantage and feigned acceptance. In May 540 Belisarius and his army entered Ravenna; the city was not looted, while the Goths were well treated and allowed to keep their properties. In the aftermath of Ravenna's surrender, several Gothic garrisons north of the Po surrendered. Others remained in Gothic hands, among which were Ticinum, where Uraias was based and Verona, held by Ildibad. Soon after, Belisarius sailed for Constantinople, where he was refused the honour of a triumph. Vitiges was named a patrician and sent into comfortable retirement, while the captive Goths were sent to reinforce the eastern armies.[33]

Gothic revival, 541–551

.jpg.webp)

Reigns of Ildibad and Eraric

| If Belisarius had not been recalled, he would probably have completed the conquest of the peninsula within a few months. This, which would have been the best solution, was defeated by the jealousy of Justinian; and the peace proposed by the Emperor, which was the next best course, was defeated by the disobedience of his generals. Between them they bear the responsibility of inflicting upon Italy twelve more years of war. |

| John Bagnell Bury History of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. II, Ch. XIX |

Belisarius' departure left most of Italy in Roman hands, but north of the Po, Pavia (which became the new capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom[35][36]) and Verona remained unconquered. Soon after Belisarius' breach of faith towards them became apparent, the Goths, at the suggestion of Uraias, chose Ildibad as their new king and he re-established Gothic control over Venetia and Liguria. Justinian failed to appoint an Italian commander-in-chief. The Roman armies neglected military discipline and committed acts of plunder. The new imperial bureaucracy made itself immediately unpopular by its oppressive fiscal demands.[37] Ildibad defeated the Roman general Vitalius at Treviso but after having Uraias murdered because of a quarrel between their wives, he was assassinated in May 541 in retribution. The Rugians, remnants of Odoacer's army who had remained in Italy and sided with the Goths, proclaimed one of their own, Eraric, as the new king, which was unexpectedly assented to by the Goths.[38] Eraric persuaded the Goths to start negotiations with Justinian, secretly intending to hand over his realm to the Empire. The Goths perceived his inactivity for what it was and turned to Ildibad's nephew, Totila (or Baduila), and offered to make him king. Totila had already opened negotiations with the Byzantines but when he was contacted by the conspirators, he assented. In the early autumn of 541 Eraric was murdered and Totila proclaimed king.[39]

Early Gothic successes

Totila enjoyed several advantages: the outbreak of the Plague of Justinian devastated and depopulated the Roman Empire in 542; the beginning of a new Roman–Persian War forced Justinian to deploy most of his troops in the east; and the incompetence and disunity of the various Roman generals in Italy undermined military function and discipline. This last brought about Totila's first success. After much urging by Justinian, the generals Constantinian and Alexander combined their forces and advanced upon Verona. Through treachery they managed to capture a gate in the city walls; instead of pressing the attack they delayed to quarrel over the prospective booty, allowing the Goths to recapture the gate and force the Byzantines to withdraw. Totila attacked their camp near Faventia (Faenza) with 5,000 men and, at the Battle of Faventia, destroyed the Roman army. Totila marched into Tuscany, where he besieged Florence. The Roman generals, John, Bessas, and Cyprian, marched to its relief but, at the Battle of Mucellium, their numerically superior forces were defeated.[40]

Southern Italy

Totila marched south, where Roman garrisons were few and weak, bypassing Rome. The provinces of southern Italy were forced to recognise his authority. This campaign was one of rapid movement to take control of the countryside, leaving the Byzantines in control of isolated strongholds, mostly on the coast, which could be reduced later. When a fortified location fell, its walls were usually razed so that it would no longer be of any military value. Totila followed a policy of treating his captives well, enticing opponents to surrender rather than resist to the end. He also tried to win over the Italian population, exemplified by Totila's behaviour during the Siege of Naples, where he allowed the city to surrender on terms in 543 and displayed, in the words of J. B. Bury, "considerable humanity" in his treatment of the defenders. He nursed the famished citizens back to strength after allowing the Byzantine garrison safe departure. Having captured Naples Totila attempted to broker a peace with Justinian. When this was refused he had copies of his appeal posted throughout Rome; despite the disfavour in which the Byzantines were held, there was no uprising in Totila's favour, which disgusted him. He marched north and besieged the city.[41][42]

Taking advantage of a five-year truce in the East, Belisarius was sent back to Italy with 200 ships in 544.[43] He successfully reoccupied much of southern Italy, but, according to Procopius, he was starved of supplies and reinforcements by a jealous Justinian and so felt unable to march to Rome's relief. Procopius describes famine during the siege, in which the ordinary Romans, who were not rich enough to buy grain from the military, were reduced to eating bran, nettles, dogs, mice and finally "each other's dung".[44] Pope Vigilius, who had fled to the safety of Syracuse, sent a flotilla of grain ships, but Totila's navy intercepted them near the mouth of the Tiber and captured them. A desperate attempt by Belisarius to relieve Rome came close to success but ultimately failed.[45] After more than a year Totila finally entered Rome on 17 December 546,[45] when his men scaled the walls at night and opened the Asinarian Gate. Procopius states that Totila was aided by some Isaurian troops from the imperial garrison who had arranged a secret pact with the Goths. Rome was plundered and Totila, who had expressed an intention to completely level the city, satisfied himself with tearing down about one third of the walls. He then left in pursuit of the Byzantine forces in Apulia.[46]

Belisarius successfully reoccupied Rome four months later in the spring of 547 and hastily rebuilt the demolished sections of wall by piling up the loose stones "one on top of the other, regardless of order".[47] Totila returned, but was unable to overcome the defenders.[48] Belisarius did not follow up his advantage. Several cities, including Perugia, were taken by the Goths, while Belisarius remained inactive and was then recalled from Italy.

In 549, Totila advanced again against Rome. He attempted to storm the improvised walls and overpower the small garrison of 3,000 men, but was beaten back. He then prepared to blockade the city and starve out the defenders, although the Byzantine commander Diogenes had previously prepared large food stores and had sown wheat fields within the city walls. However, Totila was able to suborn part of the garrison, who opened the Porta Ostiensis gate for him. Totila's men swept through the city, killing all but the women, who were spared on the orders of Totila, and looting what riches remained. Expecting the nobles and the remainder of the garrison to flee as soon as the walls were taken, Totila set traps along the roads to neighboring towns that were not yet under his control and many were killed while fleeing Rome.[49]

Byzantine reconquest, 551–554

During 550–51, the Byzantines assembled a large expeditionary force of 20,000 or 25,000 men at Salona on the Adriatic, including regular Byzantine units and a large contingent of foreign allies, notably Lombards, Heruls and Bulgars. Narses, the imperial chamberlain (cubicularius) was appointed to command in mid-551. The following spring, Narses led this Byzantine army around the coast of the Adriatic to Ancona and then turned inland, intending to march down the Via Flaminia to Rome. Near the village of Taginae, the Byzantines encountered the Ostrogothic army, commanded by Totila, who had been advancing to intercept Narses. Finding himself considerably outnumbered, Totila ostensibly entered into negotiations while planning a surprise attack, but Narses was not fooled by the ruse and deployed his army in a strong defensive position. Reinforcements having arrived, Totila launched a sudden attack at the Battle of Taginae, with a mounted assault on the Byzantine centre. The attack failed and, by evening, the Ostrogoths had broken and fled; Totila was killed in the rout. The Goths holding Rome capitulated and, at the Battle of Mons Lactarius in October 553, Narses defeated Teias and the last remnants of the Gothic army in Italy.[50]

Though the Ostrogoths were defeated, Narses soon had to face other barbarians who invaded Byzantine northern Italy and southern Gaul. In early 553, an army of about thirty thousand Franks and Alemanni crossed the Alps and took the town of Parma. They defeated a force under the Heruli commander Fulcaris and soon many Goths from northern Italy joined their forces. Narses had dispersed his troops to garrisons throughout central Italy and had wintered at Rome. After serious depredations throughout Italy, the barbarians were brought to battle by Narses on the banks of the river Volturnus. In the Battle of the Volturnus, the Byzantine phalanx held a furious Frankish assault while the Byzantine cavalry encircled them. The Franks and Alemanni were all but annihilated.[51] Seven thousand Goths held out at Campsa, near Naples, until capitulating in the spring of 555. The lands and cities across the River Po were still held by Franks, Alemanni and Goths and it was not until 562 that their last strongholds, the cities of Verona and Brixia, were subjugated. According to the Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea, the barbarian population was then allowed to live peacefully in Italy under Roman sovereignty.[52]

Aftermath

The Gothic War is often viewed as a Pyrrhic victory, which drained the Byzantine Empire of resources that might have been employed against more serious threats in western Asia and the Balkans. In the east, pagan Slavs and Kutrigurs raided and devastated the Byzantine provinces south of the Danube from 517. A century later Dalmatia, Macedonia, Thrace and most of Greece were lost to Slavs and Avars.[53] Some recent historians have taken a different view of Justinian's western campaigns. Warren Treadgold placed greater blame for the vulnerability of the Empire in the late 6th century on the Plague of Justinian in 540–541, which is estimated to have killed up to a quarter of the population at the height of the Gothic War, sapping the Empire of manpower and tax revenues needed to complete the campaign more swiftly. No ruler, no matter how wise, could possibly have anticipated the Plague, he argues, which would have been disastrous for the Empire and Italy, regardless of the attempt to reconquer Italy. However, as a result of Rome having been under attack constantly during the war, the deaths not caused by the plague continued to rise.

In Italy the war devastated the urban society that was supported by a settled hinterland. The great cities were abandoned as Italy fell into a long period of decline. The impoverishment of Italy and the drain on the Empire made it impossible for the Byzantines to hold their gains. Only three years after the death of Justinian in 565, the mainland Italian territories fell into the hands of the Germanic Lombards. The Exarchate of Ravenna, a band of territory that stretched across central Italy to the Tyrrhenian Sea and south to Naples, along with parts of southern Italy, were the only remaining Imperial holdings. After the Gothic Wars the Empire would entertain no more serious ambitions in the West. Rome would remain under imperial control until the Exarchate of Ravenna was finally conquered by the Lombards in 751. Some coastal areas of southern Italy would remain under East Roman influence, until the late 11th century, while the interior would be ruled by Lombard dukes based at Benevento and later also at Salerno and Capua.[54]

A decisive result was that Italy – united into a single political unit by the Romans in the early centuries of their expansion and remaining such throughout the Roman Empire and also under the Goths – was broken up, with the successor states often going to war with each other, until the Unification of Italy in the 19th century.[55]

The widespread destruction of Italy in the war, harsh Gothic and Byzantine reprisals of their opponents' supporters, and heavy Byzantine taxation led the Italian populace to shift allegiances: instead of loyalty to Empire, their identities were increasingly tied to religion, family and city instead.[56]

Notes

- Procopius gives the number of adult males slain as 300,000 but this is improbably high. Many thousands were killed, the rest taken as slaves and the city destroyed. (Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 205)

Further reading

- Lin, Sihong (2021). "Justinian's Frankish War, 552–ca. 560". Studies in Late Antiquity. 5 (3): 403–431.

References

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIII, pp. 453–454

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIII, pp. 454–455

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIII, pp. 456–457

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIII, p. 459

- Bury, pp. 157–161

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, pp. 159–165

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 164

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.V.1

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, pp. 170–171

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.VI

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, pp. 172–173

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 174

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.VII

- Norwich, p. 217

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 194

- Norwich 1988, p. 218.

- Procopius BG II.VII

- J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, p. 219

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XI

- Norwich, pp. 119–220

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XIII

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 198

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, pp. 198–199

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 200

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 201

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XII

- Norwich, pg. 223

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, pp. 203–205

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, pp. 205–206

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 207

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 209

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XVIII, p. 211

- Norwich, pp. 224–27

- "Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers, tant anciens que modernes, diligemment depeints au naturel par Luc Dheere peintre et sculpteur Gantois[manuscript]". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Thompson, Edward Arthur (1982). Romans and Barbarians: Decline of the Western Empire. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9780299087005.

- "Pavia Royal town". Monasteri Imperiali Pavia. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIX, p. 227

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIX, p. 228

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIX, p. 229

- Bury, p. 230

- Bury pp. 231–233

- Norwich, pp. 238–39

- J. Norwich, A Short History of Byzantium, 77

- Procopius, translation by Dewing, H B (1914) History of the Wars: Book VI (continued) and Book VII, William Heinemann Limited, London (pp. 299–301)

- Barker, John W (1966) Justinian and the Later Roman Empire Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, University of Wisconsin Press (p. 160)

- Procopius (pp. 345–349)

- Procopius p. 359

- Barker. p. 161

- Norwich, pp. 240–44

- Norwich, pp. 251–53

- Bury pp. 275–80

- De Bello Gothico IV 32, pp. 241–45

- Vlasto, pp. 155–226

- Norwich, p. 265

- "risorgimento". 3 June 2002. Archived from the original on 3 June 2002. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Patrick Amory (2003). People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–176. ISBN 9780521526357.

Sources

Primary sources

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico, Volumes I–IV

- Jordanes, De origine actibusque Getarum ("The Origin and Deeds of the Goths"), translated by Charles C. Mierow.

- Cassiodorus, Variae epistolae ("Letters"), at the Project Gutenberg

Secondary sources

- Bury, John Bagnell (2005). History of the Later Roman Empire Vols. I & II. London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4021-8368-3.

- Fauber, Lawrence H. (1991). Hammer of the Goths: The Life and Times of Narses the Eunuch. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-04126-7.

- Gibbon, Edward, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Vol. IV, Chapters 41 & 43 (2012) Radford, VA : Wilder Pub. OCLC 856929460

- Hughes, Ian (2009). Belisarius:The Last Roman General. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-59416-528-3.

- Jacobsen, Torsten Cumberland (2009). The Gothic War. Yardley: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-59416-084-4.

- Norwich, John Julius (1988). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-80251-7.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2630-6.

- Vlasto (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 838383098.