Government in medieval England

The government of the Kingdom of England in the Middle Ages was a monarchy based on the principles of feudalism. The king possessed ultimate executive, legislative, and judicial power. However, some limits to the king's authority had been imposed by the 13th century. Magna Carta established the principle that taxes could not be levied without common consent, and Parliament was able to assert its power over taxation throughout this period.

| History of England |

|---|

|

|

|

For information on English government before 1066, see Government in Anglo-Saxon England.

Crown

Inheritance and coronation

In the Norman and Angevin periods, there were still no definitive rules regarding inheritance. For example, William the Conqueror gave the Duchy of Normandy to his eldest son, Robert Curthose, but left the Kingdom of England to his third son, William II. The lack of formal rules of succession created conflict between members of the ruling dynasty. Following the death of his only legitimate son, Henry I decided that his daughter, Empress Matilda, would inherit the throne. Matilda was unpopular both for being a woman and because she was married to Geoffrey, count of Anjou—Normandy's enemy. After Henry's death, Matilda's cousin, Stephen of Blois, was quickly made king. The civil war between Matilda and Stephen became known as the Anarchy, and peace was restored only after Stephen adopted Matilda's son, Henry II, as his son and heir. In the process, Stephen's own sons were disinherited.[1]

In the Norman and Angevin periods, a reign did not officially begin until a successor's coronation. The interregnum on average lasted a month but could be shorter or longer based on political circumstances. It lasted only three days between the death of William II and the crowning of Henry I, who wanted to secure the throne for himself while his elder brother Robert Curthose was in Normandy. The political uncertainty during an interregnum meant it could be a dangerous time for the country. Before their coronation, a future king styled himself "Lord of England" or "Lord of the English". In medieval France, interregnums were avoided by practicing coregency where kings had their heirs crowned as co-kings. This occurred in medieval England only once when Henry II had his eldest son, Henry the Young King, crowned co-king.[2]

Under the Plantagenets, rules of primogeniture were more established, and a new reign was considered to have begun on the death of the old king. When Henry III died in 1272, his son Edward I became king even though he was on Crusade at the time and would not be crowned until 1274.[3]

Traditionally, an English king was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury at Westminster Abbey. As part of the ceremony, the king swore a three-fold oath to protect the church and Christian people; to prohibit crime; and to rule with justice and mercy. The clergy and people present were then asked by a bishop if they wanted him as king, to which they replied "we wish it and grant it". The king was then anointed with chrism, symbolizing the sacramental character of kingship. After the anointing, he was crowned.[4]

Rights and authority

Medieval England was a feudal monarchy. As a feudal lord, the king had certain rights and powers over his vassals.[5] The physical crown worn by kings came to symbolize all of the king's rights (see The Crown).[6] As a feudal overlord, the king had various rights over tenants-in-chief (or feudal barons) including the right:[7]

- of wardship of underage heirs

- to arrange or sell the marriages of under-age heiresses and widows

- to demand military service

- to demand payment of a feudal aid upon the marriage of the king's eldest daughter or the knighting of his eldest son

Unlike other lords, kings were anointed and had greater power. The Crown alone:[8][5]

- could coin money

- had authority over main roads

- could declare war (though it was wise for kings to obtain parliamentary consent)

- could not be sued

- had sole jurisdiction over certain crimes (but could delegate authority to private jurisdictions)

The king carried with him a special jurisdiction called the verge, which was the 12 mile area around the king's person where local courts did not have authority to hear cases. Only the courts of the royal household had jurisdiction.[9]

The Roman law principle of necessity was also an important component of the Crown's powers. If the king could demonstrate an urgent necessity, his subjects were obligated to assist him. In 1294, Edward I justified his seizure of wool based on the "certain and urgent necessity" that existed. Edward III also requested taxation on the basis of the necessity of defending the realm.[10]

Limitations

Royal authority was challenged. Henry de Bracton argued that the king was under the law, and if he went beyond the law he should be "bridled" by his earls and barons.[10]

In the 13th century, the distinction between the king and the Crown developed. In the reign of Henry III, there are some indications that the Crown was regarded as distinct from the king in terms of the alienation of royal land.[11] By the reign of Edward III, this distinction was well developed. The Crown Estate belonged to the Crown and should not be alienated by individual kings.[8]

During the reign of Edward II, the earl of Lincoln presented the Declaration of 1308 arguing that homage and allegiance were due more to the Crown than to the person of the king .[12] One of the arguments for deposing Edward II was that he had not defended the rights of the Crown, specifically that he failed to preserve royal lands and had taken evil counsel.[9]

King's council

The king's council provided the monarch with expert advice and assistance in governing the kingdom. It was involved in legal, financial, and diplomatic business. It heard important legal cases, and it could reach decisions without reference to the common law.[13] It could draft legislation in the form of administrative orders issued as letters patent or letters close.[14]

Members included the king's ministers and closest advisers, such as judges, the chancellor, and the treasurer. Members took an oath to give the king faithful counsel. The council met in the Star Chamber at Westminster Palace.[13]

Royal household

The royal household was the centre of royal government.[15] In the Middle Ages, there was no clear distinction between the royal court and the royal household. The court might refer to everyone around the king, while the household referred to the specific institution that served the king.[16] Kings traveled constantly to various parts of the kingdom. King John's household, for example, moved an average of 13 times a month. The household had to be itinerant.[17]

There were around 500 members of the household. The most important department was the wardrobe. It managed the household's finances and oversaw war spending. It was led by the keeper of the wardrobe, who was one of the king's most important ministers. The wardrobe controlled the privy seal, which was used to issue orders to the chancery and exchequer. Under Edward II, this writing office was separated from the wardrobe, and the king began using the secret seal when issuing orders to the keeper of the privy seal.[18]

The military household included bannerets, knights, squires, and sergeants-at-arms. In addition to a military role, they also served as administrators and diplomats.[16]

Departments

.jpg.webp)

The main financial department was the exchequer. The exchequer developed under Henry I (r. 1100–1135) and audited the accounts of sheriffs and other royal officials.[20] At the end of the 12th century, it moved from Winchester to a chamber adjacent to Westminster Hall.[21] The lower exchequer received payments and issued receipts in the form of tally sticks. The upper exchequer was a court called the Exchequer of Pleas.[22] The judges were called barons of the exchequer, and they conducted the annual audits.[20]

In theory, the exchequer controlled government finances. All royal revenue was supposed to be paid to the exchequer, and its officers (the treasurer and exchequer chamberlains) would pay out funds as needed to the royal household. In reality, there were periods, such as in the reign of Edward I, where the wardrobe was outside of the exchequer's control. Household officials often diverted royal revenue before it ever reached the exchequer, and the wardrobe did not always submit its accounts to be audited.[23]

The chancellor oversaw the chancery or government writing office. It was originally part of the royal chapel. The clerks in the chapel served both the king's spiritual and secretarial needs.[24] During Edward I's reign, the chancery clerks started to stay in England rather than accompany the king on foreign military expeditions. By the reign of Edward III, it was permanently based at Westminster.[25]

In 1324, there were about a hundred clerks who produced around 29,000 writs. At the head of the chancery's organization were 12 master clerks who were termed "first form" clerks. Beneath them were 12 second form clerks. Beneath them were the 24 cursitors who wrote the standardized writs. Below these were assistant clerks and servants.[25]

Government administration could be needlessly complicated. In the 14th century, a royal order could be issued originally under the king's secret seal, then sent to the privy seal office which would instruct the chancery to prepare the final writ. "Three documents were used where one would have sufficed. This might lead to long delays."[26]

Parliament

Early councils (924–1215)

Since the unification of England in the 10th century, kings had convened national councils of lay magnates and leading churchmen. The Anglo-Saxons called such councils witans. These councils were an important way for kings to maintain ties with powerful men in distant regions of the country. The witan had a role in making and promulgating legislation as well as making decisions concerning war and peace. They were also the venues for state trials, such as the trial of Earl Godwin in 1051.[27]

After the Norman Conquest, this conciliar tradition was continued. The king received regular council from the members of his curia regis (Latin for "royal court"), but he periodically enlarged the court by summoning large numbers of magnates (earls, barons, bishops and abbots) to attend a magnum concilium (Latin for "great council") to discuss national business and promulgate legislation.[28] For example, the Domesday survey was planned at the Christmas council of 1085, and the Constitutions of Clarendon were made at the 1164 council. The magnum concilium continued to be the setting of state trials, such as the trial of Thomas Becket.[29]

Nevertheless, these were not representative or democratic assemblies. They were feudal councils in which barons fulfilled their obligation to provide counsel to their lord the king.[30] Councils allowed kings to consult with their leading subjects, but such consultation rarely resulted in a change in royal policy. According to historian Judith Green, "these assemblies were more concerned with ratification and publicity than with debate".[31] In addition, the magnum concilium had no role in approving taxation as the king could levy geld (discontinued after 1162) whenever he wished.[32]

The years between 1189 and 1215 were a time of transition for the great council. The cause of this transition were new financial burdens imposed by the Crown to finance the Third Crusade, ransom Richard I, and pay for the series of Anglo-French wars fought between the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties. In 1188, a precedent was established when the great council granted Henry II the Saladin tithe. In granting this tax, the great council was acting as representatives for all taxpayers.[32]

The likelihood of resistance to national taxes made consent politically necessary. It was convenient for kings to present the great council as a representative body capable of consenting on behalf of all within the kingdom. Increasingly, the kingdom was described as the communitas regni (Latin for "community of the realm") and the barons as their natural representatives. But this development also created more conflict between kings and the baronage as the latter attempted to defend what they considered the rights belonging to the king's subjects.[33]

John's reign saw the first issuance of Magna Carta. Clause 12 was the origin of the principle of "no taxation without representation". Clause 12 stated that certain taxes could only be levied "through the common counsel of our kingdom", and clause 14 specified that this common counsel was to come from bishops, earls, and barons.[34]

Unicameral Parliament (1215–1307)

Parliament evolved out of the magnum concilium and met occasionally when summoned by the king.[35] Parliament differed from the older great council by being "an institution of the community rather than the crown". For the community of the realm, "it acts as representative, approaching the government from without, and 'parleying' with the king and his council".[36]

Before 1258, legislation was not a major part of parliamentary business.[14] It is in the reign of Edward I that Parliament passed the first major statutes. "However, they were not made by the King in Parliament, but simply announced by the king or his ministers in a parliament" [emphasis in original].[37] The actual work of law-making was done by the king and his council.[38] Completed legislation was then presented to Parliament for ratification.[39]

Parliament successfully asserted for itself the right to consent to taxation, and a pattern developed in which the king would make concessions (such as reaffirming Magna Carta) in return for grants of taxation.[40] This was its main tool in disputes with the king. Nevertheless, this proved ineffective at restraining the king as he was still able to raise lesser amounts of revenue from sources that did not require parliamentary consent:[41][42]

- county farms (the fixed sum paid annually by sheriffs for the privilege of administering and profiting from royal lands in their counties)

- profits from the eyre

- tallage on the Crown Estate, the towns, foreign merchants, and most importantly English Jews

- scutage

- feudal dues and fines

- profits from wardship, escheat, and vacant episcopal sees

Local government

Counties

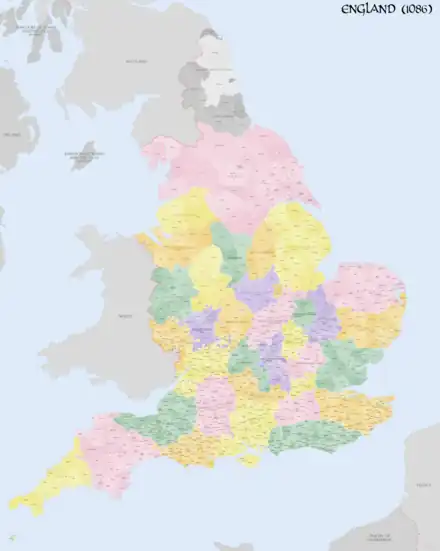

England was divided into 39 counties, which existed with only minor boundary changes until 1974 when the Local Government Act 1972 went into effect.[43]

The most important county officer was the sheriff. Sheriffs were appointed by the king and served at his pleasure. He presided over the county court, collected taxes, and paid the county farm owed to the king.[44] As the main communication channel between the Crown and the counties, the sheriff was responsible for sharing royal proclamations. He was assisted by an under-sheriff, clerks, bailiffs, and sub-bailiffs. One clerk was responsible for county finances, and another was responsible for recording writs received and actions taken.[45]

Once a sheriff paid the county farm to the exchequer, he kept any excess money he collected. This made appointment to a shrievalty profitable and desirable. Men were even willing to buy appointments. Sheriffs were chosen from the ranks of barons, royal administrators, or local gentry.[44] The Norman kings typically chose sheriffs from among the local barons, but Henry I preferred to utilize clerks and knights of the royal household—who owed their success solely to royal patronage.[46] These household officials typically appointed deputies to fulfill their duties. Henry III preferred to appoint local knights to the office, and this trend continued after his reign.[47]

The king appointed an escheator for counties north of the Trent and another for those counties south of it. These appointed sub-escheators in each county to enforce royal wardship rights and manage lands that escheated to the Crown.[48]

Hundreds

Counties were divided into 628 smaller units called hundreds. The hundred court met every two to four weeks and was attended by local landholders. Twice a year the hundred court met with the sheriff presiding to ensure that every free adult male was part of a tithing. Members of a tithing were collectively responsible for one another's conduct in a system known as frankpledge. A tithing could be fined if it failed to detain criminals.[49]

The smallest territorial unit was the vill (or township). A delegation from each vill (including the priest, reeve, and four "of the better men of the township") might be required to attend the county court.[50]

Private jurisdictions

Kings sometimes granted counties to relatives for short periods. For example, Henry I gave his wife Adeliza the county of Shropshire. Henry's illegitimate son, Reginald de Dunstanville, was given Cornwall with the title of earl of Cornwall. Richard I gave his brother John six counties, but these were forfeited due to John's rebellion in 1194.[51]

Two counties enjoyed permanent autonomy from direct royal control. These were Cheshire and Durham, which were palatine counties. Among other things, the earl of Chester and the bishop of Durham appointed their own sheriffs.[51] By the end of the 13th century, over half of all hundreds had been granted to barons, bishops, or abbeys. In these hundreds, the lord's representative presided over the hundred court, and the lord received the profits of justice.[52]

Justice system

Central courts

The king was the fount of justice.[54] Initially, important cases were heard coram rege (Latin for "in the presence of the king himself") with the advice of his curia regis. But the growth of the legal system required specialization, and the judicial functions of the curia regis were delegated to two courts sitting at Westminster Hall.[55]

The Court of Common Pleas split from the Exchequer of Pleas in the 1190s. It had jurisdiction over civil cases (such as debts, property rights, and trespass). It was staffed by a chief justice of the Common Pleas and several other justices of the Common Pleas.[56][57]

In the 1230s, the earlier coram rege court developed into the Court of King's Bench.[57] It originally traveled with the king but was permanently based at Westminster Hall by the 1300s. Cases came before the King's Bench as appeals from lower courts (including Common Pleas) by writs of error. It had jurisdiction over civil matters involving the king and criminal cases. It was staffed by the chief justice of the King's Bench and several justices of the King's Bench.[56][58]

Local courts

The hundred court had jurisdiction over minor offenses and property disputes. Before the reign of Henry II, the shire or county court had a wide-ranging jurisdiction. Most land disputes and serious criminal cases were heard there. Henry I mandated that land disputes between vassals of two different lords were also to be heard in county court.[59]

County courts met twice a year in Anglo-Saxon times, but some were meeting every three weeks by the 13th century. The court was presided over by the sheriff and attended by the local landholders. Local custom and tradition played a large role in the functioning of the county courts, and these customs varied from county to county.[60]

Henry II instituted the general eyres in which a group of between two and nine itinerant justices were assigned a circuit of counties to visit. These circuits covered the whole country with the exception of Chester and Durham, which were exempt due to their special status. The eyre justices would stay in one county for several weeks to hear cases under their jurisdiction before moving on. Their jurisdiction included among other things the pleas of the Crown, cases initiated by royal writ, criminal cases, and issues touching the rights of the Crown (wardships, etc.).[61] By 1189, there were around 35 itinerant judges, seven to nine judges per circuit.[62]

The lord of a manor automatically enjoyed the right to hold a manorial court over his vassals and tenants. Manorial courts had jurisdiction over "debt under forty shillings, contracts and conventions made within the power of the lord, cattle wounding [and other sorts of things], damage to crops by animals, assault not leading to bloodshed, trespass or damaging of timber where the king's peace was not involved ..."[63] In some cases, lords or the church were granted franchisal jurisdiction over entire hundreds. This meant their courts had authority to punish petty theft and affray. They also could hang thieves caught red-handed.[54]

Trial

In Norman times, court procedure involved the pleadings of the parties, information supplied by juries, documentary evidence, and witness testimony. In many cases, a compromise settlement was reached. When this was not possible, conclusive proof was sought through methods invoking divine intervention: trial by oath (compurgation) and trial by ordeal.[64] In criminal cases, three forms of ordeal were used: trial by hot iron, trial by cold water, and trial by combat. Trial by combat was introduced by the Normans and was frequently used when one person accused another of theft or murder. Civil cases involving property over 10 shillings were determined by battle as well.[65]

Henry II introduced a number of legal reforms that mark the origins of the common law.[66] In particular, the role of juries in both criminal and civil cases was expanded.[67] A jury was a group of men who swore to give a truthful answer (a verdict) to a question asked of them.[68] The Assize of Clarendon of 1166 required that juries of presentment identify those "accused or notoriously suspect of being a robber, murderer or thief" and provide this information to the itinerant judges when they visited the county.[69] The jury did not yet decide innocence or guilt, which was still proven by ordeal.[70]

In civil cases, such as land disputes, the Grand Assize of 1179 gave defendants the option of having the matter settled by a jury of twelve knights instead of trial by battle. Henry also introduced the petty assizes—procedures to allow speedy resolution of land disputes. These include novel disseisin, mort d'ancestor, and darrein presentment.[66] Under the petty assizes, a plaintiff initiated proceedings by purchasing a writ from the chancery. The writ instructed the sheriff to choose a jury of 12 free men. The next time a royal justice was in the county, the parties and the jury would appear before him. For novel disseisin, the jury was to answer, "Was the plaintiff evicted unjustly and without judgment from an estate of which he was in peaceful possession?"[68]

In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council forbade clergy participation in trial by ordeal. In 1219, the Crown ordered justices to find an alternative and the jury trial was chosen. The first recorded criminal jury trial occurred at Westminster in 1220. The first juries differed from modern juries in that early jurors were local men with knowledge of the case. Their job was not to weigh evidence but to decide the facts of a case using their own knowledge.[71]

Punishment

Punishments for serious crimes included execution by hanging and mutilation (such as blinding and castration). Lesser offenses were punished by amercements or financial penalties. The royal Fleet Prison in London was opened as early as the 1130s. The Assize of Clarendon required each county to have a jail in a borough or royal castle.[72]

See also

References

Citations

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 8–10.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 123–125.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 29.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 125.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 122.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 123.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 32.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 38–39.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 37.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 33.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 34.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 35.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 57.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 241.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 130.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 48.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 133.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 48 & 58.

- Starkey 2010, p. 179.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 159.

- Potter 2015, p. 82.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 58.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 59–60.

- Huscroft 2016, pp. 80–81.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 60.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 56.

- Maddicott 2009, pp. 3–4 & 8.

- Green 1986, pp. 20 & 23.

- Maddicott 2009, pp. 4–5.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 145–146.

- Green 1986, p. 23.

- Maddicott 2009, p. 6.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 123 & 140–143.

- Magna Carta clause 12 quoted in Bartlett (2000, p. 146)

- Lyon 2016, p. 66.

- Jolliffe 1961, p. 287.

- Lyon 2016, p. 79.

- Butt 1989, pp. 139–140.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 283.

- Lyon 2016, pp. 66 & 68.

- Butt 1989, p. 91.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 174–175.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 147.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 148–150.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 66–67.

- Jolliffe 1961, p. 197.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 66.

- Prestwich 2005, p. 67.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 156–157.

- Downer (1972, p. 100, 7.7b) quoted in Bartlett (2000, p. 158)

- Bartlett 2000, p. 148.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 157.

- "Manuscript Collection". Inner Temple Library. Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 178.

- Fitzroy 1928, p. 10.

- Potter 2015, pp. 82–83.

- Burt 2013, p. 28.

- Prestwich 2005, pp. 60–61.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 177.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 151–153.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 190–191.

- Potter 2015, pp. 48, 50 & 62.

- Jolliffe 1961, p. 148.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 179–180.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 181–182.

- Lyon 2016, pp. 44–45.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 192–193.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 192.

- Potter 2015, p. 48.

- Bartlett 2000, p. 193.

- Potter 2015, pp. 77 & 79.

- Bartlett 2000, pp. 184 & 186.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert (2000). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings, 1075-1225. New Oxford History of England. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780199251018.

- Burt, Caroline (2013). Edward I and the Governance of England, 1272–1307. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139851299.

- Butt, Ronald (1989). A History of Parliament: The Middle Ages. London: Constable. ISBN 0-0945-6220-2.

- Downer, L. J., ed. (1972). Leges Henrici Primi. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. OCLC 389304.

- Fitzroy, Almeric (1928). The History of the Privy Council. London: John Murray.

- Green, Judith A. (1986). The Government of England under Henry I. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511560248. ISBN 9780511560248.

- Huscroft, Richard (2016). Ruling England, 1042–1217 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1138786554.

- Jolliffe, J. E. A. (1961). The Constitutional History of Medieval England from the English Settlement to 1485 (4th ed.). Adams and Charles Black.

- Lyon, Ann (2016). Constitutional History of the UK (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-20398-8.

- Maddicott, John (2009). "Origins and Beginnings to 1215". In Jones, Clyve (ed.). A Short History of Parliament: England, Great Britain, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scotland. The Boydell Press. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-1-843-83717-6.

- Maddicott, J. R. (2010). The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-58550-2.

- Potter, Harry (2015). Law, Liberty and the Constitution: A Brief History of the Common Law. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781783270118.

- Prestwich, Michael (2005). Plantagenet England, 1225–1360. New Oxford History of England. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198228449.

- Starkey, David (2010). Crown and Country: A History of England through the Monarchy. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0007307715.