Governments of Felipe González

The governments of Felipe González (1982-1996) occurred during the second period of the reign of Juan Carlos I of Spain.

.jpg.webp)

Felipe González governed for nearly 14 years because his party, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), won four consecutive general elections (1982, 1986, 1989, and 1993) - the first three by absolute majority, a "feat" "in Spanish, and even European, parliamentary history". This period saw the consolidation of democracy (after the democratic transition of 1975–1982), the integration of Spain into the European Community in 1986 (European Union from 1992 onwards), and its transformation into a society comparable to that of its European neighbors.[1]

Elections of 1982

The general elections of October 28, 1982 had the highest participation rate of democracy - 79.97% and more than 20 million voters -[1] thus having a "relegitimizing effect", in the words of Santos Juliá, on democracy and the process of political transition.[2]

With the slogan Por el cambio (English: For Change), the PSOE scored a resounding victory by getting more than 10 million votes, almost 5 million more than in 1979, meaning 48.11% of the voters and an absolute majority in the Congress of Deputies (202 deputies) and in the Senate. The second most voted party, People's Alliance (106 deputies), got half of the votes (5.5 million) and was 20% points behind - although its results improved considerably compared to 1979, going from 6% to 26% of the votes - becoming from then on in the new conservative alternative to the socialist power. The PCE (with 4 deputies) and UCD (with 12) were practically swept off the map, as well as the Democratic and Social Centre of Adolfo Suárez (which only got 2 deputies). In addition, the extreme right wing lost the only deputy it had, and the Spanish Solidarity party, promoted by the coup leader Antonio Tejero, didn't even get 30,000 votes.[2][3]

With this result, described as an authentic "electoral earthquake", the party system underwent a radical change, since the imperfect two-party system (UCD/PSOE) of 1977 and 1979 had been replaced by a dominant party system (the PSOE).[4] The new party system was consolidated in the municipal and autonomous community elections of May 1983, another important victory for the PSOE, as 12 of the 17 autonomous communities were governed by socialists - with an absolute majority in 7 of them -[5] while continuing to hold the main cities' mayorships. Only the autonomous governments of Galicia, Cantabria, the Balearic Islands (of People's Alliance), Catalonia (of CiU) and the Basque Country (of PNV) were outside socialist control.[6]

The elections of 1982 have been considered by most historians to be the end of the political transition process initiated in 1975. The first reason being the high turnout, the highest ever recorded up to that time (79.97%), which reaffirmed the citizens' commitment to the democratic system and demonstrated that the "return to the past" advocated by the "involutionist" sectors did not have the support of the people. Secondly, because for the first time, the political alternation typical of democracies took place, thanks to the free exercise of the vote by the citizens. Furthermore, because a party that had nothing to do with Franco's regime assumed the government - since it was one of the defeated parties in the Civil War.[7]

The socialist project: Spain's "modernization"

.jpg.webp)

The political program developed by the governments presided over by Felipe González was not a project of "socialist transformation" - the only nationalization carried out was that of the high voltage electricity network - but of "modernization" of Spanish society to put it on a par with the rest of the "advanced" democratic societies. Its historical reference was the moderate socialism of Indalecio Prieto.[8]

The government plan presented by the PSOE during the 1982 election campaign was very ambitious. It proposed consolidating democracy and tackling the economic crisis - its flagship promise was the creation of 800,000 jobs - as well as adapting productive structures to a more efficient and competitive economy, helping small and medium-sized businesses and reconverting large public industrial companies, also achieving a fairer and more egalitarian society with the universalization of health care, education and pensions. As Santos Juliá pointed out, the PSOE undertook to "change everything without revolutionizing anything" within a "project for the regeneration of the State and society" which Felipe González summarized with the slogan "Que España funcione" (English: Let Spain work) thanks to a "gobierno que gobierna" (English: government that governs).[9]

However, the economic and political situation that Calvo Sotelo's government bequeathed the country was very complicated. Economic stagnation continued, with unemployment exceeding 16%, inflation not dropping below 15% and a staggering budget deficit. ETA terrorism continued and the threat of a coup d'état had not disappeared, as demonstrated by the new coup attempt that Calvo Sotelo's government was able to stop and that was planned for the eve of the October 28th elections.[10] On September 30, based on information obtained by the secret services, four chiefs and officers - who had planned for a large number of civilian and military commandos to take control of strategic points in Madrid and then declare a "state of war" - were arrested. The public was not informed of the facts, and in April 1984, two colonels and two lieutenant colonels were sentenced to 12 years in prison and expelled from the Army.[11]

Consolidation of the democratic system

Military policy: end of the coup threat

The Socialist government realized that in order to consolidate the democratic regime in Spain it was necessary to put an end to its two main enemies: "putschism" and "terrorism". Concerning the former, several measures were implemented to "professionalize" the Army and subordinate it to civilian power, so that the idea of an "autonomous" military power became completely out of the question. Thus, as Santos Juliá pointed out:[12]

"The shadow of the military coup ceased to hover over Spanish politics for the first time since the beginning of the Transition."[12]

Narcís Serra, the Minister of Defense of the first Socialist government, submitted to Parliament a Law on the Army Staff, which provided for a progressive reduction of 20% in the number of generals, chiefs, officers and non-commissioned officers. Similar to the Azaña's military reform of the Second Republic, it sought to create a more professional and efficient army, ending the endemic problem of an excessive number of commanders - from 66,000 in 1982 to 57,600 in 1991.[13] In 1984, Serra also presented the Organic Law of Defense and Military Organization, which placed the Board of Joint Chiefs of Staff under the direct authority of the minister and integrated the Navy, the Air Force and the Army into the same organization chart through the creation of the new figure of the chief of the Defence Staff.[12] It also integrated military jurisdiction into civilian jurisdiction through the creation of a Special Chamber of the Supreme Court, and reduced the historical military regions from nine to six.[14]

The socialist government still faced a last coup attempt in June 1985, that was thwarted by the intelligence services and was not made public until more than ten years later. The plan consisted of setting off an explosive charge under the presidential tribune of the Armed Forces Day parade - to be held on the first Sunday of June in La Coruña - and blaming ETA. Following this, putschism disappeared completely from Spanish political life.[15]

Additionally, the length of compulsory military service was reduced from 15 to 12 months in 1984 and from 12 to 9 in 1991, plus conscientious objection was regulated, resulting in a massive influx of young people willing to perform the alternative civilian service - there were also draft dodgers who were convicted for refusing to perform either one or the other.[13]

Education policy and extension of rights and freedoms

The team of the Minister of Education of the first Socialist government José María Maravall drafted the Organic Law for the Right to Education (in Spanish, Ley Orgánica reguladora del Derecho a la Educación or LODE) that, among other things, recognized and regulated the subsidies received by private educational centers, mostly religious, that provided basic education, henceforth called "concerted" centers, and whose management would involve the teachers and parents of the students through the school board. Although it was opposed by conservative sectors - People's Alliance, with the support of the National Catholic Confederation of Family Parents and Student Parents (in Spanish, Confederación Católica Nacional de Padres de Familia y Padres de Alumnos or CONCAPA) and the Federation of Religious Educators, appealed the law before the constitutional court, which rejected the appeal -[16] according to Santos Juliá:[17]

"The Law was received with relief by the Episcopal Commission for Education, who saw it as the necessary guarantee to keep getting substantial funds from the State - more than 100,000 million pesetas - that private education had been receiving without any legal regulation."[17]

Minister Maravall also implemented the University Reform Act (in Spanish, Ley de Reforma Universitaria or LRU) which granted broad economic and academic autonomy to universities and established a system to achieve faculty stability.[17] The so-called Non-tenured Professors (PNNs) were granted the status of State employees through an "exceptional and controversial" competition of "suitability".[18] The university reform went hand in hand with the creation of new universities and a significant increase in the number of scholarships, resulting in an increase of university students to over one million for the first time in 1990.[19]

The Cortes also approved several laws that developed the rights and freedoms recognized in the Constitution, such as the Habeas Corpus, Freedom of assembly, Foreigners, and Trade Union Freedom.[20] The most controversial was the Abortion law, approved in spring 1985, which allowed the voluntary termination of pregnancy in three cases: rape, malformation of the fetus, and serious physical or psychological risk to the mother. The Catholic Church campaigned in defense of the "right to life" and People's Alliance appealed to the Constitutional Court, but the Court ruled in favor of the law.[21]

In July 1985, the election system of 20 members of the General Council of the Judiciary was modified and all of them were appointed by the Cortes - only 8 were appointed until then and the other 12 corresponded to the associations of judges and magistrates. The Organic Law of the Judiciary Power approved by the Socialists was appealed to the Constitutional Court, but the Court rejected the appeal.[22] According to David Ruiz, this change in the election procedure of the council had "the purpose of neutralizing the conservative, if not reactionary, ideology of a significant proportion of judges and magistrates".[23] In contrast, critics of this reform accused it of being a clear attempt to politicize the judiciary, an accusation that was reinforced by polemical statements by Alfonso Guerra about "the death of Montesquieu", the 18th-century philosopher and advocate of the separation of powers.

End of the "State of Autonomies"

Besides approving the few statutes of autonomy that were still pending, there was a huge decentralization of public spending, transferring to the autonomous communities the powers determined by their respective statutes and which until then had been exercised by the central State. By 1988, the average expenditure of the autonomous communities had already reached 20% of total public spending, and since then it has continued to increase. Thus, in a short time, as Santos Juliá pointed out, "Spain went from being the most centralist state in Europe to one of the most decentralized".[24]

However, both the government of the Basque Country, presided since 1984 by the peneuvist José Antonio Ardanza and that of Catalonia, presided since 1980 by the leader of CiU Jordi Pujol, continued to demand greater levels of self-government and opposed the "leveling" of all the autonomous communities, also accusing the government of reducing their competences by resorting to organic laws, all of this aggravated by the continuity of ETA terrorism.

Anti-terrorism policy

Regarding the Security Forces, the National Police was created, but the military character of the Guardia Civil was maintained.[25]

In the anti-terrorism policy, the first socialist governments maintained the policy of social reinsertion of imprisoned terrorists that condemned ETA's violence and dissociated themselves from it,[11] but under its mandate increased the dirty war against ETA led by the GAL - a self-described "Antiterrorist Liberation Group" born in 1981 during the last UCD government and which remained "entrenched" in "the structure of State security" after the Socialists came to power.[26]

According to historian David Ruiz, the GAL was a "group initially made up of members of the State security forces and later swelled by some Spanish and foreign mercenaries linked to the former Political-Social Brigade of Francoism that, making use of the reserved funds of the Ministry of the Interior, decided to take justice into their own hands and respond with weapons to ETA terrorism, hoping to provoke the political collaboration of the French Government in the anti-terrorist struggle". The first GAL action was the kidnapping of two French citizens in Hendaye in 1981, followed by the kidnapping in 1983 of Segundo Marey, a Spanish citizen living in Hendaye who was mistaken for an ETA collaborator and who was released 9 days later. By 1987 the GAL attacks caused 28 fatalities, the vast majority of them in the "French sanctuary".[25]

The government attempted a direct negotiation with the ETA leadership to initiate a process similar to that leading to the self-dissolution of the political-military ETA in 1981. However, the so-called "Algiers talks" failed to produce any results, leading the government to seek a major anti-terrorism pact that would also include democratic Basque nationalism, something eventually achieved with the signing of the Ajuria Enea Pact in January 1988.[27]

Shortly after the signing of the Ajuria Enea Pact, two policemen, José Amedo and Michel Domínguez, were arrested, charged with involvement in the kidnapping of Segundo Marey, among other crimes committed by the GAL, aggravated by their use of reserved funds from the Ministry of the Interior to carry out the attacks. Awareness of this fact forced the Minister of the Interior José Barrionuevo to resign and he was replaced by José Luis Corcuera, who had to take charge of the new Law of Citizen Security, popularly known as the "law of the door kick" because it authorized public order forces to break into any home where agents suspected a crime was being committed without a warrant. This law would be overturned by a ruling of the Constitutional Court.[28]

Integration into EEC and NATO membership

.jpg.webp)

From the outset, the socialist governments proposed the full integration of Spain into Europe. Finally, in 1985, the negotiations to join the European Economic Community (EEC, then formed by 10 members) culminated, and on June 12, the Treaty of Accession was signed in Madrid. On January 1, 1986, Spain - together with Portugal - joined the EEC. However, the other big bet of the socialist foreign policy, the membership of Spain in NATO under certain conditions, "unleashed the greatest political confrontation of the 1980s".[29]

Accession to the European Economic Community

When the Socialists assumed the government, the negotiations for the accession to the European Economic Community were still blocked due to the "pause" in the enlargement imposed by the French President Giscard d'Estaing. To speed up the process, the government of Felipe González tried to soften the relations with France (whose presidency was now held by the socialist François Mitterrand) allowing a rapid progress of the negotiations. By late March 1985, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Fernando Morán and the Secretary of State for the Community Manuel Marín announced the end of the process. On June 12, 1985, the Treaty of Accession to the EEC was signed, and on January 1, 1986, Spain joined the EEC together with Portugal, increasing the number of EEC members from 10 to 12.[30] As David Ruiz pointed out, joining the EEC was "an event of great significance because it ended Spain's secular isolation".[29]

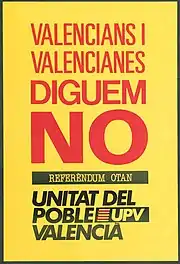

NATO membership referendum

After Spain's accession to EEC, it was time to call the promised referendum on Spain's NATO membership. But Felipe Gonzalez and his government announced that they were going to defend Spain's continued membership in NATO, although under three mitigating conditions:[31]

- Non-incorporation into the military structure.

- The prohibition to install, stockpile or introduce nuclear weapons, and;

- The reduction of US military bases in Spain.

González previously had to convince his own party in the 30th Congress of December 1984, plus the turnaround regarding NATO provoked the resignation of the Minister of Foreign Affairs Fernando Morán.[31]

According to Santos Juliá, the main factors influencing the change of attitude of the PSOE government were:[32]

- The pressure from the United States and several European countries.

- The relationship between staying in NATO and Spain's incorporation into the EEC, and;

- The attitude in favor of closer ties with the Alliance adopted very early on by the Ministry of Defense.

Added to this was a view that it was unwise to leave NATO when tensions of the Second Cold War were heightening.[32]

Faced with the PSOE's "turnabout", the banner of NATO rejection was taken up by the Communist Party of Spain - now led by the Asturian Gerardo Iglesias that had replaced Santiago Carrillo who ended up leaving the PCE to found the Communists' Unity Board - forming a broad coalition of organizations and left-wing parties including socialists that left the PSOE because they disagreed with the change in their party's position. United Left, a coalition that contested the general elections of June 1986, emerged from this. Meanwhile, the "pro-Atlantist" People's Alliance paradoxically opted for abstention, leaving the government on its own which constituted, in the words of David Ruiz, a "painful strategy... that would discredit the political career of its founder, Manuel Fraga, as an aspirant to the Spanish government".[33]

Against the odds, Felipe González - who announced that he would resign if the "NO" vote won, something that seemed to have influenced many voters - eventually managed to turn the polls around and the "YES" vote won in the March 12, 1986 referendum, albeit by a narrow margin. A total of 11.7 million voters (52%) were in favor of the membership, 9 million (40%) voted against, while 6.5 million voted blank. The "NO" vote won in four communities: Catalonia, the Basque Country, Navarre and the Canary Islands.[34] In the Basque Country, the anti-NATO campaign favored the growth of Herri Batasuna, the party of the Abertzale left, winning 5 places in the October 1986 elections.[35]

The referendum result, "the toughest challenge of his long term in office",[36] strengthened Felipe González's leadership, both in his party and in the country as a whole, as was evidenced in the general elections of that year where the PSOE once again won an absolute majority, although with 18 fewer deputies than in 1982. It was also true that the economic crisis had been overcome and the country had entered a phase of strong expansion that would last until 1992.[35][37]

Economic and social policy

Social policies: culmination of the welfare state

Though it began during the last stage of Franco's dictatorship and was developed during the transition under the UCD governments, the Welfare state comparable to that of other advanced European countries was completed during the socialist period, since it was then when healthcare (General Health Law, passed in 1986) and public education (Organic Law of General Organization of the Education System or LOGSE, approved in 1990) were extended to the entire population. A new organization of the educational system was implemented and compulsory education was extended to 16 years of age. There was also a considerable increase in social spending on pensions and unemployment benefits, in addition to other social benefits.[38]

This was possible because the socialist governments increased the tax burden, amounting to 33.2% of GDP in 1993 as compared to 22.7% in the previous 20 years,[20] taking advantage of the favorable economic situation in 1985–1992, when the Spanish economy overcame the crisis and grew above the European average.[38]

Economic recovery and industrial reconversion

The Minister of Economy and Finance of the first Socialist government, Miguel Boyer, and his successor from 1985 onwards, Carlos Solchaga, implemented a policy of adjustments and wage moderation to consolidate the economy and reduce inflation - at 16% per year when the Socialists first came to office. They succeeded in reducing the price increase to below 10%, but at the cost of an increase in unemployment, that in 1985 exceeded 20% of the active population, a record figure - in 1985, there were 10.6 million employed people, 2 million less than 9 years earlier.[39]

However, 2 other variables played a role in the unemployment rise: influx of the 1960s baby boom generation and the mass entry of women into the job market. Not only did the government fail to create the promised 800,000 jobs, but it also increased the number of unemployed by about the same amount.[40]

Likewise, the first socialist government reformed the Workers Statute in 1984 in order to make the labor market more "flexible", resulting in a precariousness of employment by considerably increasing the number of temporary contracts as opposed to permanent ones.[20]

Simultaneously, it also dealt with the modernization of the productive structures by means of an ambitious program of industrial reconversion that the UCD governments had not dared to apply due to the electoral cost it would have. Following the guidelines of the Libro blanco de la reindustralización (English: Reindustrialization White Paper) presented in May 1983 by Minister Carlos Solchaga, obsolete or bankrupt companies were closed, credits were given to companies so that they could introduce the necessary technological improvements to increase their productivity and make them more competitive, etc. Most affected sectors were the iron and steel and shipbuilding industries, especially the oversized public companies inherited from Franco's dictatorship. These sectors saw the greatest conflicts, with frequent confrontations between the workers and the security forces. The toughest confrontations occurred in the Valencian town of Sagunto, whose Altos Hornos del Mediterráneo was intended to be closed, as it eventually happened. The industrial reconversion also included the privatization of state-owned companies, as in the case of SEAT, which was sold to the German multinational Volkswagen.[41]

This program was coupled with heavy investments in infrastructure - also due to the influx of European funds after joining the EEC - which allowed Spain to build a network of highways and freeways and to start the construction of the Madrid–Seville high-speed rail line, which came into operation in 1992.[38]

Split between PSOE and UGT

The positive effects of the economic policy became evident in 1985, when the Spanish economy began a strong expansion that lasted until 1992.[42] However, speculative capital movements also flourished during those years, led by people linked to the financial world who sought quick profits and who were presented by certain conservative media as role models: Mario Conde, the "Albertos" (Alberto Cortina and Alberto Alcocer), Javier de la Rosa, etc.[43]

Within this context, UGT and the PSOE split for the first time in their history. The rift began when the Government stopped enforcing the election program - agreed between the PSOE and the UGT on economic and social matters - and instead implemented a harsh economic policy of adjustments, made the labor market more "flexible", and started industrial reconversion, in addition to postponing the introduction of the 40-hour working week. UGT Secretary General Nicolás Redondo accused the Government of "tremendous arrogance", although in 1984 UGT still participated in the policy of social agreement, signing a Social Economic Agreement with the CEOE employers' association, from which Workers' Commissions excluded itself.[44][45]

The first public confrontation took place in 1985, regarding the draft Pension Law, which the Government did not negotiate with the UGT and that increased the years of contribution to collect a pension from 10 to 15 years, and extended from 2 to 8 years the period for the calculation of the pension. UGT secretary general, Nicolás Redondo, a socialist deputy in Congress, voted against the law and Felipe González withdrew from the May 1st demonstration.[46]

The definitive split between UGT and the Socialist government was staged before the television cameras on February 19, 1987, during the live debate between Nicolás Redondo and the then Minister of Economy and Finance Carlos Solchaga, who had opposed the 2% wage increase to compensate for the workers' sacrifice during the crisis. At one point during the debate, Redondo told the minister: "Your problem, Carlos, is the workers; you are in the wrong trench". A few months later Redondo left his position in Congress, together with another UGT leader, Antón Saracíbar.[47]

The split resulted in confrontation when the government presented its Youth Employment Plan which UGT and Workers' Commissions rejected - according to the unions the plan introduced what would later be known as "junk contracts" - leading to the call for a general strike for December 14, 1988, under the motto "Por el giro social" (English: For the social turnaround).[48]

The strike was a total success and the country was completely paralyzed without any incidents - an estimated 8 million workers, as well as self-employed workers and students, participated in the strike. Employers, in turn, described the strike as "antisocial, illegitimate and inopportune".[49]

According to Santos Juliá, the general strike responded to "a growing dissatisfaction with the way of doing politics rather than with the policies developed by the Government".[50] A viewpoint shared by David Ruiz, who adds that:[51]

"[The general strike of 14D] signified the largest labor abstention against a government decision ever recorded in Spanish history, and it was also without the political motivation, without the demands for changes in government and/or in the form of the State that accompanied the two most resounding general strikes of the century, those recorded in August 1917 and in October 1934."[51]

Due to the strike's success, the President considered resigning, but ultimately did not, although he did withdraw the controversial Youth Employment Plan. The economic growth also made it possible to revalue pensions and increase unemployment coverage, especially for the long-term unemployed, which led to a considerable expansion of social spending.[52] In addition, non-contributory pensions were created, benefiting 123,000 people in 1992. The Social Security budget exceeded 8 trillion pesetas that year, compared to 3 trillion pesetas in 1982.[53]

Socialist decline (1989-1996)

The 4th Legislature (1989-1993)

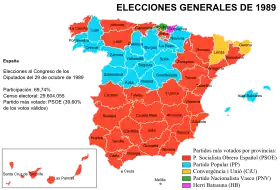

Felipe González called general elections for October 1989, where he once again won the absolute majority, but this time by only one deputy - a relative setback previously seen in the municipal elections of 1987, where the Socialists lost their majority in the big cities though keeping the municipalities of less than 50,000 inhabitants. As Santos Juliá pointed out:[54]

"The honeymoon between the Socialist Party and public opinion, which began in 1982, was coming to an end, although voters were in no hurry to vote for the rival party."[54]

_Logo_(1993-2000).svg.png.webp)

The People's Party ran for the first time in the 1989 elections. Created from the "refoundation" of People's Alliance carried out in the Extraordinary Congress held in January of the same year, the People's Party defined itself as "a broad-based party where liberal, conservative and Christian democratic ideas fit and coexist comfortably", comparable, therefore, with the European center-right. As head of the list for the elections, Manuel Fraga - who regained the presidency of the party after the defeat of Antonio Hernández Mancha, to whom he yielded the leadership of People's Alliance after the loss in the general elections of 1986 - nominated José María Aznar, then president of the Junta de Castilla y León, who was elected president of the PP in the 10th Congress of March 1990, while Manuel Fraga held the presidency of the Xunta de Galicia after winning the autonomous elections of December 1989. The "re-founded" PP obtained 25.6% of the votes and 107 deputies, far behind the 176 of the PSOE.[55]

Meanwhile, United Left increased the number of votes (9.1%), which translated into 17 deputies. The Democratic and Social Centre of Suárez did not exceed 8%, a setback that was confirmed in the municipal elections and autonomic elections of May 1991, obtaining 4%. These elections saw the PSOE take a major blow as a result of the outbreak of the first corruption scandal, the "Guerra case", resulting in the loss of almost half of the mayorships in the most important cities it held since 1979, including Madrid, Seville and Valencia. However, it kept the autonomous communities it governed except Navarra, where the PP and Navarrese People's Union obtained the majority.[56]

The Guerra case, uncovered in 1989, was the first scandal to undermine confidence in the PSOE and its administration. It was named after the brother of the vice-president, who was accused of illicit enrichment and influence peddling from the place he held in the Seville Government Delegation without holding any position, because he was his brother's "assistant". Alfonso Guerra played down the importance of the matter and, defiantly, refused to resign.[57] PSOE's leadership supported him and the Socialist parliamentary group objected to the opposition's request to set up a committee of inquiry to investigate the case in Congress. The consequence of this refusal was the strained relations between the PSOE, on the one hand, and the PP and United Left, on the other, resulting in the "festering of parliamentary life".[58] In the end, Felipe González chose to dismiss Alfonso Guerra in January 1991. In turn, Juan Guerra was sentenced in 1995 to 2 years in prison, a fine of 50 million pesetas and 6.5 years of ineligibility to hold public office.[59]

Alfonso Guerra's exit from the Government deepened the internal division of the PSOE, which had emerged in the 32nd Congress held in November 1990, during which the "guerrista" sector (loyal to the still vice-president and critical of the Government) and the "renovador" sector (loyal to President Gonzalez) clashed. This sparked the beginning of a dull struggle, intensified by the emergence of a new corruption scandal in May 1991, revealed by the newspaper El Mundo, the Filesa case, which this time involved the whole party.[59][60]

Filesa was the name of one of the three ghost companies created to illegally finance the PSOE by charging non-existent reports to industrialists and bankers between 1989 and 1991, in exchange for the awarding of public contracts, and for which the companies of the plot did not pay the corresponding taxes. In March 1993, a report by the experts of the Ministry of Finance established that Filesa had received more than 1,000 million pesetas by this means.[59][61] President Felipe Gonzalez brushed off the matter, stating that he had "learned about it from the press."[62] Judge Marino Barbero charged 39 people, 8 of whom would be sentenced in 1997 by the Supreme Court to penalties ranging from 11 years of prison to 6 months of arrest, a sentence that would be ratified by the Constitutional Court 4 years later and that only punished the fiscal crime, since the crime of illegal financing of political parties did not exist at that time.[63]

A third case of corruption that affected the PSOE was the so-called "Ibercorp case", also uncovered by the newspaper El Mundo in February 1992. The governor of the Bank of Spain, Mariano Rubio, was accused and imprisoned for keeping an account with black money in Ibercorp, the financial entity of his friend Manuel de la Concha, former trustee of the Madrid Stock Exchange, also prosecuted. The former Minister of Economy and Finance, Carlos Solchaga, who had appointed Rubio, had to resign as deputy.[64] This scandal showed the connections between the socialist government and the so-called "beautiful people", an expression used to designate the businessmen and nouveau riche who had emerged in the socialist era.[63]

As David Ruiz pointed out, this accumulation of corruption scandals gave rise to "an almost generalized political disappointment among citizens. Not only did the hostility of the opposition in parliament towards the socialist group increase considerably, but the recovery of public ethics became almost a popular clamor". The PSOE became so questioned that it lacked credibility when it filed the accusation of a corruption case involving the People's Party, the "Naseiro case", named after the treasurer of the PP Rosendo Naseiro. This case was finally dismissed by the Supreme Court when it annulled the recordings of telephone conversations on which the accusation was based as evidence.[65]

In the midst of this political climate, two major events scheduled for 1992 took place, placing Spain at the forefront of the world's media - it was "Spain's great year in the world," according to David Ruiz. The Summer Olympics - the first of the "post-Cold War" period, where 171 countries participated (the highest number ever recorded) - were a complete success. The Spanish athletes won 32 medals, whereas in the previous Olympic Games in Seoul they had only won 4 medals. Likewise, 112 countries and 23 international organizations were represented at the Seville Expo, attended by 18 million people, many of them arriving to the Andalusian capital on the Madrid-Seville AVE. The two events provided "the opportunity to present Spain in the Columbus Quincentenary as a modern country, definitely away from the romantic stereotype (of charanga, tambourine, bandits and toreros)".[66]

Spain's new image was accompanied by the strengthening of its international role, as evidenced by the birth of the Ibero-American Summits, the celebration in Madrid of the Middle East Peace Conference and Spain's active participation in the construction of Europe, such as the Schengen Agreement in May 1991 and, above all, the Maastricht Treaty that transformed the European Community into the new European Union. Likewise, the agreement reached in the referendum on Spain's permanence in NATO was complied with and the US bases at Zaragoza and Torrejón de Ardoz were dismantled, while those at Rota and Morón de la Frontera remained, and the Spanish government sent three Navy units to support the allied military operations led by the United States during the first Gulf War of 1990–1991.[67]

The two major events of 1992 concealed the fact that a strong economic recession had begun, which resulted in a brutal increase in unemployment that would reach an unprecedented figure of 3.5 million people, or 24% of the active population. Socialist leaders recognized that 1992, which was to be the year of Spain's projection of modernity to the world, was "catastrophic".[68] In May 1992, a general strike was called by UGT and Workers' Commissions in protest against the government's "decretazo" (English: big decree), which cut unemployment benefits.[69] However, in 1992 the Government scored a remarkable victory to its anti-terrorist policy thanks to French collaboration: the three highest leaders of ETA were arrested in the town of Bidart, near the Spanish border.[53]

The rift in the unity of the party became evident again during the discussion of the strike bill presented by the Government, which was criticized by the Socialist parliamentary group, where the "guerristas" had the majority. The dispute was settled by advancing the elections to June 1993.[60][70]

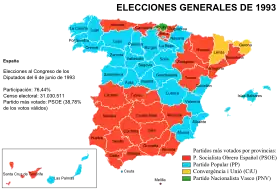

The "legislature of tension" (1993-1996)

Surprisingly, in the elections of June 1993 the PSOE won again and the People's Party of José María Aznar - who was convinced of its victory - was defeated.[60] The PSOE won 159 seats, compared with 141 by the PP, while United Left led by Julio Anguita got 18 deputies.[71] According to Santos Julià, the key to the PSOE's unexpected triumph "was largely due to the leadership of Felipe González, who assured his voters that he had understood the 'message' and had himself supported, as number two in the Madrid candidacy, by Baltasar Garzón, the judge who was most important for his investigations into the dirty war against ETA and the black money of drug trafficking".[72] However, the Socialists did not repeat the absolute majority they had held since 1982 - with 17 fewer deputies - therefore, to govern, Felipe González had to reach a parliamentary agreement with the Catalan and Basque nationalists - ruling out a pact with United Left, as some members of the "guerrista" sector had insinuated.[72]

The most pressing task of the fourth government of Felipe González was to face the economic crisis. The Minister of Economy and Finance Pedro Solbes presented at the end of 1993 a set of Urgent Measures for the Promotion of Employment, among which the part-time and internship contracts of the previous Youth Employment Plan were included again, as well as the legalization of temporary employment agencies. Opposition to the so-called "junk contracts" culminated in a general strike called by UGT and Workers' Commissions for January 27, 1994, that was a great success, constituting, according to David Ruiz, "the last workers' general strike of the century."[73] By contrast, the Socialist Government did reach consensus with the rest of the political forces and with the trade unions on the issue of pensions, which resulted in the agreement known as the Toledo Pact in April 1995.[73]

Another important field of the Government's action was foreign policy, in which the Spanish participation in the NATO intervention in the Yugoslavian war was outstanding - two Spanish F-18 fighters, together with others from other NATO countries, bombed Serbian positions in Bosnia. This renewed commitment to NATO resulted in the appointment of the then Socialist Minister of Foreign Affairs Javier Solana as Secretary General of NATO.[74]

However, the main problem that the socialist government of Felipe González had to face was the emergence of new scandals, resulting in a harsh confrontation with the opposition, both the Popular Party and United Left, thus the fourth socialist mandate came to be known as the "legislature of tension."[75]

In late 1993, the Bank of Spain, backed by the Government, intervened the Spanish Credit Bank, and its president Mario Conde was removed from office. A year later, Conde was prosecuted for fraud and sent to prison. Another "shark" of finances, Javier de la Rosa, was also arrested for swindling and embezzlement in the Gran Tibidabo company, and as Spanish representative of the Kuwaiti investment group KIO. He was jailed in October 1994, leaving prison in February after paying a bail of 1 billion pesetas.[76]

Among the new scandals, the most spectacular and the one with the greatest popular and media impact was the "Roldán case". In November 1993 Luis Roldán, the first non-military director of the Civil Guard in its history, was arrested, accused of having amassed a fortune thanks to the collection of illegal commissions from work contractors of the Benemérita and the appropriation of the reserved funds of the Ministry of the Interior. Four months later, in April 1994, Roldán fled.[77] The former Minister of the Interior who appointed Roldán, José Luis Corcuera, had to resign as a deputy, as did the Minister of the Interior at the time, Antoni Asunción, for letting him escape.[64] Roldán was arrested a year after his escape in Laos and returned to Spain, where he was prosecuted and sentenced to 28 years in prison and a fine of 1.6 billion pesetas - despite some media estimations that his fortune, deposited in Swiss banks, exceeded 5 billion pesetas.[78]

Another case of careerism within the PSOE was that of Gabriel Urralburu, a former priest who became president of the Autonomous Community of Navarre, and who was sentenced to 11 years in prison for collecting commissions from construction companies that obtained public contracts.[78]

Such scandals opened a new breach of trust in the Socialist government that resulted in demands for the resignation of the President by José María Aznar, leader of the People's Party, and Julio Anguita, general coordinator of United Left.[79]

The 1994 European Parliament elections were held in this setting, and for the first time the Popular Party surpassed the PSOE in number of votes - obtaining 40% of the votes as opposed to 30% for the Socialists,[80] leading to a demand for general elections, but Felipe González refused once he confirmed that he still had the support of CiU.[79] From then on, José María Aznar adopted the "machacona invectiva" (English: repetitive invective) of "Váyase, señor González" (English: Go away, Mr. González) in every parliamentary intervention, cheered by the deputies of the "popular" parliamentary group.[81]

A month before the European elections of June 1994, Judge Baltasar Garzón quit his position as a member of Congress and as Government Delegate for the National Plan on Drugs - apparently disappointed by the lack of political will of Felipe González to tackle corruption - and returned to the National Court. He then reopened the GAL case and granted provisional release to policemen José Amedo and Michel Domínguez who had been convicted in 1988 for their participation in several attacks attributed to the Antiterrorist Liberation Group, and who were willing to tell everything they knew once the Government did not approve their pardon, as they had been promised.[82][83]

Amedo and Domínguez's statements led to the arrest of several high-ranking officials of the Socialist administration for their alleged participation in the kidnapping and frustrated murder of the French citizen Segundo Marey, mistaken for a member of ETA by a GAL commando. In December 1994, the civil governor of Vizcaya and director general of State Security during the first Socialist government Julián Sancristóbal was arrested, followed by Rafael Vera, former secretary of State for Security, and Ricardo García Damborenea, secretary general of the Socialists of Vizcaya when Marey was kidnapped. Since the former Minister of the Interior José Barrionuevo, a Socialist deputy, was also implicated, Garzón had to transfer the Marey case to the Supreme Court, which immediately presented the request to the Cortes to prosecute him, which was granted by 159 votes in favor and 122 against.[82][83]

In January 1996, Supreme Court magistrate Eduardo Moner charged Barrionuevo as the alleged head of an armed gang directed from the Ministry of the Interior, confirming Garzón's accusation that "a terrorist plot linked to Interior officials" had been set - presumably under cover although it could not be proven - by President Felipe González, who some media had described as "Mr. X" of the scheme. However, the PSOE leadership did not fail to show solidarity with their accused party colleagues. Finally, Barrionuevo and his successor in the Ministry of the Interior, José Luis Corcuera, were acquitted in January 2002 on charges of having appropriated reserved funds, while Vera and Sancristóbal were sentenced to between 6 and 7 years in prison.[82][83]

Another major scandal related to the dirty war against ETA was uncovered in March 1995. The Civil Guard general Enrique Rodríguez Galindo was arrested by order of the National Court judge Javier Gómez de Liaño for his alleged involvement in the "Lasa and Zabala case", the kidnapping and subsequent murder of José Antonio Lasa and José Ignacio Zabala, alleged members of ETA captured in France by the GAL in 1983 and whose bodies, buried in quicklime, were found in Busot (Alicante) two years later. Trial was held in April 2000 and Rodríguez Galindo and other commanders and civil guards of the barracks of Intxaurrondo (Guipúzcoa), together with the former governor of Guipúzcoa Julen Elgorriaga, were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 67 to 71 years.[84][85]

A new scandal emerged shortly after, known as the "CESID papers" scandal and that would show, according to David Ruiz, the "unusual heights" reached by "the strategy of harassment of Felipe González' government." It was about the theft by the second chief of the secret service, Colonel Juan Alberto Perote, of a series of documents that apparently implicated more socialist politicians in the "GAL case" and that Perote, according to the newspaper El País, had delivered to Mario Conde to blackmail the high authorities of the State to neutralize the legal actions taken against him and Javier de la Rosa. Part of the documents were transcripts of illegal wiretaps, forcing the Vice President Narcís Serra, Minister of Defense at the time of the wiretaps, and his successor in office, Julián García Vargas, to resign.[85][86] García Vargas also resigned for his alleged involvement in speculative actions on Renfe land when he held the presidency of the railway company before being appointed Minister of Defense.[65] In 2001, the Supreme Court upheld the sentence of the National Court, which convicted seven members of the CESID, including General Emilio Alonso Manglano and Colonel Perote, for illegal wiretapping.[87]

In May 1995, the municipal elections and autonomic elections were held, in a context defined by the attack perpetrated by ETA on April 20, from which the leader of the opposition, José María Aznar, miraculously escaped unharmed, and the arrest and surrender in Laos of the fugitive Luis Roldán. The victory was once again for the People's Party, which was almost 5 points ahead of the PSOE - it obtained 35.2% of the votes cast compared to 30.8% for the Socialists. Almost all the provincial capitals and the cities with the largest population became governed by the PP.[88]

Faced with a series of scandals, the leader of the CiU and president of the Generalitat of Catalonia, Jordi Pujol, withdrew the parliamentary support of the CiU deputies to the Government, thus leaving the government as a minority in the Cortes. President Felipe González had no choice but to call an early general election.[86][89]

Elections of 1996

In the general elections of March 3, 1996, the People's Party obtained 156 Congress deputies, while the PSOE was left with 141. The great disappointment of the electoral result was for United Left, that expected to come close to the PSOE, and even surpass it, but ended up with 21 deputies.[86]

The PP won the elections but not by the wide margin expected, beating the PSOE by only 300,000 votes - 9.7 million versus 9.4 million - and falling far short of the absolute majority of 176 deputies. Nevertheless, the PP achieved its goal of removing the Socialists from power,[86] "after trying hard for more than a decade."[81] Thus began the governments of José María Aznar.

See also

References

- Ruiz (2002), p. 69

- Juliá (1999), p. 261

- Ruiz (2002), p. 69-70

- Ruiz (2002), p. 70-71

- Ruiz (2002), p. 70

- Juliá (1999), p. 261-262

- Juliá (1999), p. 261"The elections of October 1982 have been attributed a religitimizing effect on democracy and have been considered the end of the process of political transition. In truth, the elections stopped the tendency towards growing abstention and dispelled all doubts regarding the level of legitimacy democracy could have among Spaniards."

- Ruiz (2002), p. 71-72

- Juliá (1999), p. 260; 262

- Juliá (1999), p. 260-261

- Ruiz (2002), p. 76

- Juliá (1999), p. 263-264

- Ruiz (2002), p. 75

- Ruiz (2002), p. 74-75

- Ruiz (2002), p. 76

- Ruiz (2002), p. 78-79

- Juliá (1999), p. 264

- Ruiz (2002), p. 78

- Ruiz (2002), p. 95

- Juliá (1999), p. 265

- Ruiz (2002), p. 79-80

- Juliá (1999), p. 264-265

- Ruiz (2002), p. 79

- Juliá (1999), p. 265-266

- Ruiz (2002), p. 77

- Ruiz (2002), p. 77-78

- Ruiz (2002), p. 86-87

- Ruiz (2002), p. 96-97

- Ruiz (2002), p. 80

- Juliá (1999), p. 267

- Ruiz (2002), p. 81-82

- Juliá (1999), p. 266-267

- Ruiz (2002), p. 80; 86

- Ruiz (2002), p. 82-83

- Ruiz (2002), p. 86

- Ruiz (2002), p. 83

- Juliá (1999), p. 268-269

- Ruiz (2002), p. 87

- Juliá (1999), p. 263

- Ruiz (2002), p. 73

- Ruiz (2002), p. 72-73

- Juliá (1999), p. 268

- Ruiz (2002), p. 88

- Juliá (1999), p. 269-270

- Ruiz (2002), p. 89-90

- Ruiz (2002), p. 74; 90

- Ruiz (2002), p. 90

- Ruiz (2002), p. 90-91

- Ruiz (2002), p. 91

- Juliá (1999), p. 271

- Ruiz (2002), p. 89

- Ruiz (2002), p. 92

- Ruiz (2002), p. 96

- Juliá (1999), p. 270-271"The result at the polls - which made it possible for him to govern for the third time without the need for coalitions - is largely attributable to the voters' reluctance to vote for a party that seemed to be anchored on the right - and for many, on the extreme right - of the political map."

- Ruiz (2002), p. 85; 93-94

- Ruiz (2002), p. 94-95

- Juliá (1999), p. 271; 273

- Ruiz (2002), p. 97-98

- Ruiz (2002), p. 99

- Juliá (1999), p. 273

- Juliá (1999), p. 271-272

- Ruiz (2002), p. 99-100

- Ruiz (2002), p. 100

- Juliá (1999), p. 274-275

- Ruiz (2002), p. 101

- Ruiz (2002), p. 103-104

- Ruiz (2002), p. 105-106

- Juliá (1999), p. 272-273

- Ruiz (2002), p. 106

- Ruiz (2002), p. 106-107

- Ruiz (2002), p. 107

- Juliá (1999), p. 273-274

- Ruiz (2002), p. 109

- Ruiz (2002), p. 109-110

- Ruiz (2002), p. 110

- Ruiz (2002), p. 111

- Ruiz (2002), p. 112

- Ruiz (2002), p. 112-113

- Juliá (1999), p. 275

- Ruiz (2002), p. 108

- Ruiz (2002), p. 115

- Juliá (1999), p. 275-276

- Ruiz (2002), p. 113-114

- Juliá (1999), p. 276

- Ruiz (2002), p. 114

- Juliá (1999), p. 277

- Ruiz (2002), p. 100-101

- Juliá (1999), p. 276-277

- Ruiz (2002), p. 114-115

Bibliography

- Juliá, Santos (1999). Un siglo de España. Política y sociedad (in Spanish). Madrid: Marcial Pons. ISBN 84-9537903-1.

- Ruiz, David (2002). La España democrática (1975-2000). Política y sociedad (in Spanish). Madrid: Síntesis. ISBN 84-9756-015-9.

- Tusell, Javier (1997). La transición española. La recuperación de las libertades (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16-Temas de Hoy. ISBN 84-7679-327-8.

.jpg.webp)