Dragoman of the Porte

The Dragoman of the Sublime Porte (Ottoman Turkish: tercümân-ı bâb-ı âlî; Greek: [μέγας] διερμηνέας της Υψηλής Πύλης), Dragoman of the Imperial Council (tercümân-ı dîvân-ı hümâyûn), or simply Grand or Chief Dragoman (tercümân başı), was the senior interpreter of the Ottoman government and de facto deputy foreign minister. From the position's inception in 1661 until the outbreak of the Greek Revolution in 1821, the office was occupied by Phanariotes, and was one of the main pillars of Phanariote power in the Ottoman Empire.

History

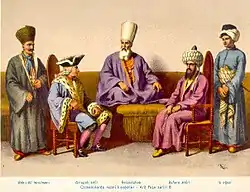

In the Ottoman Empire, the existence of official interpreters or dragomans (from the Italian rendering drog[o]man of Arabic tardjumān, Ottoman tercümân) is attested from the early 16th century. They were part of the staff of the reis ül-küttab ('head secretary'), who was responsible for foreign affairs within the Imperial Council. As few Ottoman Turks ever learned European languages, from early times the majority of these men were of Christian origin—in the main Austrians, Hungarians, Poles, and Greeks.[1]

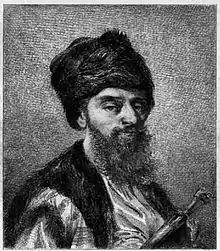

In 1661, the Grand Vizier Ahmed Köprülü appointed the Greek Panagiotis Nikousios as Chief Dragoman to the Imperial Council. He was in turn succeeded in 1673 by another Greek, Alexander Mavrocordatos.[1][2] These men began a tradition where almost all subsequent Grand Dragomans of the Porte were of Greek origin, or Hellenized Balkan Christians, and members of a small circle of Phanariote families, such as the Mavrocordatos, Ghica, Caradja or Callimachi clans.[1][2] Many of the Phanariotes had previously served in the staffs of the European embassies in Constantinople.[3] Nikousios, for instance, had previously (and for a time concurrently) served as translator for the Austrian embassy.[4]

All dragomans had to be proficient in the 'three languages' (elsine-i selase) of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish that were commonly used in the empire, as well as a number of foreign languages (usually French and Italian),[5] but the responsibilities of Dragoman of the Porte went beyond that of a mere interpreter, and were rather those of a minister in charge of the day-to-day conduct of foreign affairs.[6] As such the post was the highest public office available to non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire.[7]

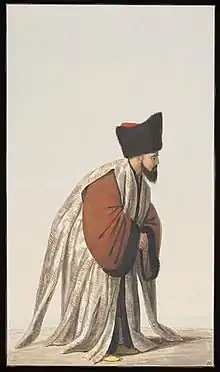

Nikousios and his successors managed to attach to their office a number of great privileges, such as tax exemption for themselves, their sons, and 20 members of their retinue; exemption from all customs fees for items destined for their personal use; immunity from all courts except from that of the Grand Vizier; permission to dress in the same kaftans as the Ottoman officials, and use ermine fur; or the permission to ride a horse. These made the position highly coveted, and the object of the Phanariotes' aspirations and rivalries.[8] The salary of the Dragoman of the Porte amounted to 47,000 kuruş annually.[9]

The success of the post led to the creation of a similar post, that of Dragoman of the Fleet, in 1701.[6][9][10] The latter often served as a stepping-stone to the office of Grand Dragoman.[9] There were also junior dragomans, for example for the Ottoman army, or for the Morea Eyalet, but these positions were never formalized in the same manner.[5] From 1711, many former Grand Dragomans or Dragomans of the Fleet were appointed to the positions of princes (voivodes or hospodars) of the tributary Danubian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. These four offices formed the foundation of Phanariote prominence in the Ottoman Empire.[11][12]

The Phanariotes maintained this privileged position until the outbreak of the Greek Revolution in 1821: the then Dragoman of the Porte, Constantine Mourouzis was beheaded, and his successor, Stavraki Aristarchi, was dismissed and exiled in 1822.[1][13] The position of Grand Dragoman was then replaced by a guild-like Translation Bureau, staffed initially by converts like Ishak Efendi, but quickly exclusively by Muslim Turks fluent in foreign languages.[1][14]

List of Dragomans of the Porte

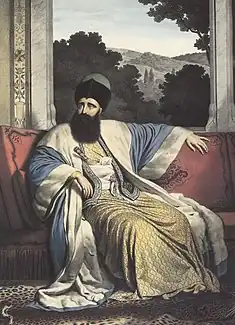

| Name | Portrait | Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panagiotis Nikousios | 1661–1673[15] | ||

| Alexander Mavrocordatos |  |

1673–1709[15] | |

| Nicholas Mavrocordatos |  |

1689–1709[15] | Son of Alexander. Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1711–1715) and Prince of Wallachia (1715–1716, 1719–1730)[15] |

| John Mavrocordatos | 1709–1717[15] | Son of Alexander. Subsequently Caimacam of Moldavia (1711) and Prince of Wallachia (1716–1719)[15] | |

| Grigore (II) Ghica |  |

1717–1727[15] | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1726–1733, 1735–1739, 1739–1741, 1747–1748) and of Wallachia (1733–1735, 1748–1752)[15] |

| Alexander Ghica | 1727–1740[16] | 1st term[16] | |

| John Theodore Callimachi |  |

1741–1750[16] | 1st term[16] |

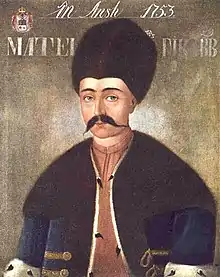

| Matei Ghica |  |

1751–1752[15] | Son of Grigore. Subsequently Prince of Wallachia (1752–1753) and of Moldavia (1753–1756)[15] |

| John Theodore Callimachi |  |

1752–1758[16] | 2nd term. Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1758–1761)[16] |

| Grigore (III) Ghica |  |

1758–1764[16] | Son of Alexander. Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1764–1767, 1774–1782) and of Wallachia (1768–1769)[16] |

| George Caradja | 1764–1765[16] | ||

| Skarlatos Caradja | 1765–1768[16] | Son of George. 1st term.[16] | |

| Nicholas Soutzos | 1768–1769[16] | ||

| Mihai Racoviță |  |

1769–1770 | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1703–1705, 1707–1709, 1716–1726) and of Wallachia (1730–1731, 1741–1744) |

| Skarlatos Caradja | 1770–1774[16] | 2nd term[16] | |

| Alexander Ypsilantis |  |

1774[16] | Subsequently Prince of Wallachia (1774–1782, 1796–1797) and of Moldavia (1786–1788)[16] |

| Constantine Mourouzis |  |

1774–1777[16] | Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1764–1765).[16] Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1777–1782) |

| Nicholas Caradja | 1777–1782[16] | Son of Skarlatos. Subsequently Prince of Wallachia (1782–1783)[16] | |

| Michael (I) Drakos Soutzos |  |

1782–1783[16] | Subsequently Prince of Wallachia (1783–1786, 1791–1793, 1801–1802) and of Moldavia (1793–1795)[16] |

| Alexander Mavrocordatos Firaris |  |

1782–1783[16] | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1785–1786)[16] |

| Alexandru Callimachi |  |

1785–1788[16] | 1st term.[16] |

| Manuel Caradja | 1788–1790[16] | ||

| Alexander Mourouzis |  |

1790–1792[16] | Son of Constantine. Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1792, 1802–1806, 1806–1807) and of Wallachia (1793–1796, 1799–1801).[16] |

| George Mourouzis | 1792–1794[16] | Son of Constantine. 1st term.[16] | |

| Alexandru Callimachi |  |

1794–1795[16] | 2nd term. Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1795–1799)[16] |

| George Mourouzis | 1795–1796[16] | 2nd term.[16] | |

| Constantine Ypsilantis |  |

1796–1799[16] | Son of Alexander. Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1799–1801) and of Wallachia (1802–1806).[16] |

| Alexandros Soutzos |  |

1799–1801[16] | Son of Nicholas. Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1797–1799). Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1801–1802) and of Wallachia (1819–1821).[16] |

| Scarlat Callimachi |  |

1801–1806[16] | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1806, 1812–1819).[16] |

| Alexandros M. Soutzos | 1802–1807[17] | ||

| Alexander Hangerli |  |

1806–1807[16] | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1807).[16] |

| John Caradja |  |

1807–1808[16] | 1st term.[16] |

| John N. Caradja | 1808[16] | Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1799–1800).[16] | |

| Demetrios Mourouzis | 1808–1812[17] | Elder brother of Panagiotis. In 1812 he took part in the negotiations which ended the war with Russia. The Ottomans became dissatisfied with the peace settlement after Napoleon began his invasion of Russia in June, and Mourouzis fell under suspicion of having furthered the Russian interest. He was summarily executed at the Topkapi Palace.[18] | |

| Panagiotis Mourouzis | 1809–1812[16] | Younger brother of Demetrios. Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1803–1806).[16] | |

| John Caradja |  |

1812[16] | 2nd term. Subsequently Prince of Wallachia (1812–1819).[16] |

| Iakovos Argyropoulos | 1812–1817[17] | Previously Dragoman of the Fleet (1809)[17] | |

| Michael Soutzos |  |

1817–1819[17] | Subsequently Prince of Moldavia (1819–1821)[17] |

| Constantine Mourouzis | 1821[17] | ||

| Stavraki Aristarchi | 1821–1822[17] | ||

References

- Bosworth 2000, p. 237.

- Patrinelis 2001, p. 181.

- Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 237.

- Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 238.

- Philliou 2011, p. 11.

- Eliot 1900, p. 307.

- Strauss 1995, p. 190.

- Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 242.

- Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 243.

- Strauss 1995, p. 191.

- Patrinelis 2001, pp. 180–181.

- Philliou 2011, pp. 11, 183–185.

- Philliou 2011, pp. 72, 92.

- Philliou 2011, pp. 92ff..

- Philliou 2011, p. 183.

- Philliou 2011, p. 184.

- Philliou 2011, p. 185.

- Hart, Patrick; Kennedy, Valerie; and Petherbridge, Dora (Eds.) (2020), Henrietta Liston's Travels: The Turkish Journals, 1812 - 1820, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 140 - 141

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (2000). "Tard̲j̲umān". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X: T–U (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 236–238. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Eliot, Charles (1900). Turkey in Europe. London: Edward Arnold.

- Patrinelis, C. G. (2001). "The Phanariots Before 1821". Balkan Studies. 42 (2): 177–198. ISSN 2241-1674.

- Philliou, Christine M. (2011). Biography of an Empire: Governing Ottomans in an Age of Revolution. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26633-9.

- Strauss, Johann (1995). "The Millets and the Ottoman Language: The Contribution of Ottoman Greeks to Ottoman Letters (19th-20th Centuries)". Die Welt des Islams. 35 (2): 189–249. doi:10.1163/1570060952597860.

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos E. (1973). Ιστορία του νέου ελληνισμού, Τόμος Δ′: Τουρκοκρατία 1669–1812 – Η οικονομική άνοδος και ο φωτισμός του γένους (Έκδοση Β′) [History of modern Hellenism, Volume IV: Turkish rule 1669–1812 – Economic upturn and enlightenment of the nation (2nd Edition)] (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Emm. Sfakianakis & Sons.

.svg.png.webp)