Languages of the Ottoman Empire

The language of the court and government of the Ottoman Empire was Ottoman Turkish,[3] but many other languages were in contemporary use in parts of the empire. Although the minorities of the Ottoman Empire were free to use their language amongst themselves, if they needed to communicate with the government they had to use Ottoman Turkish.[4]

| Languages of the Ottoman Empire | |

|---|---|

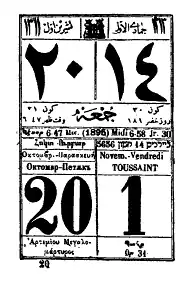

1911 Ottoman calendar in Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Hebrew/Judeo-Spanish, French and Bulgarian | |

| Official | Ottoman Turkish |

| Recognised | Arabic,[1][2] Persian[1][2] |

| Minority | Albanian, Armenian, Aromanian, Azerbaijani, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic (Suret), Western Neo-Aramaic, Berber (Tamazight), Bulgarian, Cappadocian Greek, all the Caucasian languages, Coptic, Chagatai Turkic, Crimean Tatar, Crimean Gothic, Croatian, Domari, Gagauz, Galician, Georgian, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Aramaic, Judaeo-Spanish, Kazakh, Kurdish, Latin,[dn 1] Laz, Megleno-Romanian, Polish, Pontic Greek, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Ruthenian, Serbian, Slovak, Ukrainian, Urum, Yevanic, Zazaki, Bosnian |

| Foreign | French |

The Ottomans had altogether three influential languages known as "Alsina-i Thalātha" (The Three Languages) that were common to Ottoman readers: Ottoman Turkish, Arabic and Persian.[2] Turkish, spoken by the majority of the people in Anatolia and by the majority of Muslims of the Balkans except in Albania, Bosnia, and various Aegean Sea islands; Persian, initially a literary and high-court language used by the educated in the Ottoman Empire before being displaced by Ottoman Turkish;[1] and Arabic, which was the legal and religious language of the empire[1] and was also spoken regionally, mainly in Arabia, North Africa, Mesopotamia and the Levant.[5] Throughout the vast Ottoman bureaucracy Ottoman Turkish language was the official language, a version of Turkish, albeit with a vast mixture of both Arabic and Persian grammar and vocabulary.

Some ordinary people had to hire special "request-writers" (arzuhâlcis) to be able to communicate with the government.[6] The ethnic groups continued to speak within their families and neighborhoods (mahalles) with their own languages (e.g., Jews, Greeks, Armenians, etc.) In villages where two or more populations lived together, the inhabitants would often speak each other's language. In cosmopolitan cities, people often spoke their family languages, many non-ethnic Turks spoke Turkish as a second language. Educated Ottoman Turks spoke Arabic and Persian, as these were the main non-Turkish languages in the pre-Tanzimat era.[7][1]

In the last two centuries, French and English emerged as popular languages, especially among the Christian Levantine communities. The elite learned French at school, and used European products as a fashion statement. The use of Ottoman Turkish for science and literature grew steadily under the Ottomans, while Persian declined in those functions. Ottoman Turkish, during the period, gained many loanwords from Arabic and Persian. Up to 88% of the vocabulary of a particular work would be borrowed from those two languages.[5]

Linguistic groups were varied and overlapping. In the Balkan Peninsula, Slavic, Greek and Albanian speakers were the majority, but there were substantial communities of Turks and Romance-speaking Romanians, Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians. In most of Anatolia, Turkish was the majority language, but Greek, Armenian and, in the east and southeast, Kurdish and Aramaic languages were also spoken. In Syria, Iraq, Arabia, Egypt and north Africa, most of the population spoke varieties of Arabic with, above them, a Turkish-speaking elite. However, in no province of the Empire was there a unique language.[8]

Translations of government documents

As a result of having multiple linguistic groups, the Ottoman authorities had government documents translated into other languages, especially in the pre-Tanzimat era.[9] Some translators were renowned in their language groups while others chose not to state their names in their works.[10] Documents translated into minority languages include the Edict of Gülhane, the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856,[9] the Ottoman Penal Code (Ceza Kanunnamesi), the Ottoman Commercial Code (Ticaret Kanunnamesi), the Provincial Reform Law (Vilayet Kanunnamesi), the Ottoman Code of Public Laws (Düstur),[11] the Mecelle,[12] and the Ottoman Constitution of 1876.[13]

Alsina-i Thalātha

Ottoman Turkish

Throughout the empire's history, Turkish enjoyed official status,[1] having an important role as the Lingua Franca of the multi-lingual governing elite throughout the empire.[14] Written in Perso-Arabic script, the Ottoman variant of Turkic language was replete with loan words from Arabic and Persian.[15] The 1876 Constitution of the Ottoman Empire stated that Ottoman Turkish was the official language of the government and that in order to take a public office post one had to know Ottoman Turkish.[16]

Vekayi-i giridiyye, a newspaper published in Egypt after 1830, was the first newspaper in the Turkish language in the empire; there was a version in both Turkish and Greek.[9]

Arabic

Arabic was the liturgical and legal language of the empire,[1] being one of the two major languages for Ilm (Ottoman Turkish: ulûm), along with Ottoman Turkish.[1][17]

Being the language taught in the Madaris,[18] the Ottoman legal apparatus in particular relied on old Arabic Hanafi legal texts, that until the late empire remained untranslated, and the Ottoman jurists would also continue to author new jurisprudential works in the language.[19][20][21] Indeed, Arabic was the major language for the works of the Hanafi school,[22] which was the official Maddhab of the empire.[23] However some Arabic legal works were translated into Turkish.[24]

The Arabic newspaper Al Jawaib began in Constantinople, established by Fāris al-Shidyāq a.k.a. Ahmed Faris Efendi (1804-1887), after 1860. It published Ottoman laws in Arabic,[25] including the Ottoman Constitution of 1876.[26]

Several provincial newspapers (vilayet gazeteleri in Turkish) were in Arabic.[25] The first Arabic language newspaper published in the Arab area of the empire was Ḥadīqat al-Akhbār, described by Strauss, also author of "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," as "semi-official".[27] Published by Khalīl al-Khūrī (1836–1907), it began in 1858.[28] There was a French edition with the title Hadikat-el-Akhbar. Journal de Syrie et Liban.[29] Others include the Tunis-based Al-Rāʾid at-Tūnisī and a bilingual Ottoman Turkish-Arabic paper in Iraq, Zevra/al-Zawrāʾ; the former was established in 1860 and the latter in 1869. Strauss said the latter had "the highest prestige, at least for a while" of the provincial Arabic newspapers.[30]

During the Hamidian period, Arabic was promoted in the empire in the form of Pan-Islamist propaganda.[31]

The Düstur was published in Arabic,[10] even though Ziya Pasha wrote a satirical article about the difficulty of translating it into Arabic, suggesting that Ottoman Turkish needs to be changed to make governance easier.[32]

In 1915, the Arabic-medium university Al-Kuliyya al-Ṣalaḥiyya (Ottoman Turkish: Salahaddin-i Eyyubî Külliyye-i islamiyyesi) was established in Jerusalem.[33]

Persian

Persian was the language of the high-court and literature between the 16th and 19th centuries.[1]

There was a Persian-language paper, Akhtar ("The Star"), which was established in 1876 and published Persian versions of Ottoman government documents, including the 1876 Constitution.[25]

Strauss stated that "some writers" stated that versions of the Takvim-i Vekayi in Persian existed.[9]

Non-Muslim minority languages

There was a Greek-language newspaper established in 1861, Anatolikos Astēr ("Eastern Star"). Konstantinos Photiadis was the editor in chief,[34] and Demetrius Nicolaides served as an editor.[35] In 1867 Nicolaides established his own Greek-language newspaper, Kōnstantinoupolis. Johann Strauss, author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," wrote that the publication "was long to remain the most widely read Greek paper in the Ottoman Empire."[35] Nicolaides also edited Thrakē ("Thrace"; August 1870 – 1880) and Avgi ("Aurora"; 6 July 1880 – 10 July 1884).[36]

There was a bilingual Turkish-Greek version of Vekayi-i giridiyye (Κρητική Εφημερίς in Greek).[9] The Edict of Gülhane and the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856 were published in Greek.[9]

The Düstur was published in Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, and Judaeo-Spanish, as well as Turkish in Armenian characters.[10] The Mecelle was also published in Greek, with Photiadis and Ioannis Vithynos as co-translators.[37] A version of the Düstur also appeared in Karamanli Turkish.[10]

The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was published in multiple non-Muslim languages, including those in Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, and Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino).[13] There was also a version in Turkish written in Armenian characters.[38]

Regarding the Romance languages, Romanian was spoken in Dobruja, parts of Wallachia (Brăila, Giurgiu and Turnu Măgurele) and Moldavia (Budjak) annexed by the Ottoman Empire, the Danube shores, Yedisan (Transnistria) and the Temeşvar Eyalet. Megleno-Romanian was spoken in Moglena while Aromanian was spoken all over the Balkans, but south the Romanian-speaking parts.

Foreign languages

Constantinos Trompoukis and John Lascaratos stated in "Greek Professors of the Medical School of Constantinople during a Period of Reformation (1839–76)," that beginning in the 1600s many Christians took up certain educational professions as many Ottoman Muslims did not focus on foreign languages.[39]

French

However French in particular became more prominent during and after the Tanzimat era,[40] as Westernisation increased and since, at the time, it was a major language of the philosophical and diplomatic fields along with sciences.[7] It was the sole common language of European origin among all people with high levels of education, even though none of the native ethnic groups in the empire used French as their native language.[28] Lucy Mary Jane Garnett wrote in Turkish Life in Town and Country, published in 1904, that within Constantinople (Istanbul), "The generality of men, in official circles at least, speak French".[41] Among the people using French as a lingua franca were Sephardic Jews, which adopted French as their primary language due to influence from the Alliance Israélite Universelle.[13] Two factions opposing Sultan Abdul Hamid, the Ottoman Armenian and Young Turk groups, both used French.[42]

Strauss, also the author of "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," wrote that "In a way reminiscent of English in the contemporary world, French was almost omnipresent in the Ottoman lands."[43] Strauss also stated that French was "a sort of semi-official language",[44] which "to some extent" had "replaced Turkish as an 'official' language for non-Muslims".[13] Strauss added that it "assumed some of the functions of Turkish and was even, in some respects, capable of replacing it."[44] As part of the process, French became the dominant language of modern sciences in the empire.[17]

Laws and official gazettes were published in French,[40] aimed at diplomats and other foreign residents,[28] with translation work done by employees of the Translation Office and other government agencies.[44] The employees were nationals of the empire itself.[45] Strauss stated that as Ottoman officials wished to court the favour of people in Europe, "the French translations were in the eyes of some Ottoman statesmen the most important ones" and that due to the features of Ottoman Turkish, "without the French versions of these documents, the translation into the other languages would have encountered serious difficulties."[28] Such translated laws include the Edict of Gülhane, the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856,[9] and the Ottoman Constitution of 1876.[38] Strauss wrote that "one can safely assume that" the original drafts of the 1856 edict and some other laws were in French rather than Ottoman Turkish.[46] Strauss also wrote that the Treaty of Paris of 1856 "seems to have been translated from the French."[40] In particular versions of official documents in languages of non-Muslims such as the 1876 Constitution originated from the French translations.[40] French was also officially the working language of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the period after the Crimean War.[47]

In addition, newspapers written in other western European languages had editions in French or editions with portions in French.[43] The cities of Constantinople, Beirut, Salonika (Thessaloniki), and Smyrna (İzmir) had domestically-published French-language newspapers.[43]

In 1827 Sultan Mahmud II announced that the empire's first medical school, the Imperial Military School of Medicine, would for the time being teach in French; that school and a civil medical school both taught in French. By the 1860s advocates of French medium instruction and Ottoman Turkish medium instruction were engaged in a conflict; Turks advocated for Turkish while minoritarian groups and foreigners advocated for French.[43] Spyridon Mavrogenis, employed in the imperial medical school as a professor, advocated for the usage of French.[48] The empire later made Ottoman Turkish the language of the two medical schools.[43] Another French-medium medical school was Beirut's Faculté Française de Médecine de Beyrouth. The Turkish-medium Şam Mekteb-i tıbbiyye-i mulkiyye-i şahane in Damascus acquired books written in French and enacted French proficiency tests.[49] In 1880 the dual Ottoman Turkish and French-medium law school, Mekteb-i Hukuk, was established.[33]

Others

Garnett wrote that, as of 1904, in regards to males of "official circles" within Constantinople, "many read, if they do not speak, English".[41]

In regards to foreign languages in general, Garnett stated "in all large towns there are quite as many Turks who read and write some foreign language as would be found in a corresponding class in this country [meaning the United Kingdom]."[41]

Gallery

1896 calendar in Salonika (now Thessaloniki), a cosmopolitan city; the first three lines in Ottoman script

1896 calendar in Salonika (now Thessaloniki), a cosmopolitan city; the first three lines in Ottoman script

Sources

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Strauss, Johann (2016-07-07). "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire". In Murphey, Rhoads (ed.). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Routledge.

Notes

- In Republic of Ragusa which was under Ottoman protection.

References

- Saydam, Y., 2009. Language problems in the Ottoman empire. Ekklesiastikos Pharos, 91(1), pp.38-57.

- Strauss, J., 2003. Who Read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th-20th centuries)?. Middle Eastern Literatures, 6(1), pp.39-76.

- "The Rise of the Turks and the Ottoman Empire". Archived from the original on 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- Language use in the Ottoman Empire and its problems, 1299-1923 Archived 2012-12-24 at archive.today

- Spuler, Bertold, translated from German into English by Muhammad Ismail Marcinkowski. "Persian Historiography Outside Iran in Modern Times: Pre-Ottoman Turkey and Ottoman Empire" (Chapter 13.5). In: Persian historiography and geography. Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd, 2003. ISBN 9971774887, 9789971774882. Start: 68. CITED: pages 68-69. -- Original German content in: Spuler, Bertold. "Die historische und geographische literatur in persischer sprache." in: Iranian Studies: Volume 1 Literatur. BRILL, 1 June 1968. ISBN 9004008578, 9789004008571. Chapter "Türkei", start p. 163, cited pp. 163-165. Content also available at ISBN 9789004304994, as "DIE HISTORISCHE UND GEOGRAPHISCHE LITERATUR IN PERSISCHER SPRACHE." Same pages cited: p. 163-165.

- Kemal H. Karpat (2002). Studies on Ottoman social and political history: selected articles and essays. Brill. p. 266. ISBN 90-04-12101-3.

- Küçükoğlu, Bayram (2013). "The history of foreign language policies in Turkey". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier. 70 (70): 1090–1094. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.162. - From: Akdeniz Language Studies Conference 2012 - Cited: p. 1091.

- Imber, Colin (2002). "The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-26.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 22 (PDF p. 24)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 24 (PDF p. 26)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 23 (PDF p. 25)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 31 (PDF p. 33)

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books PT193.

- Darling, L.T., 2012. 5. Ottoman Turkish: Written Language and Scribal Practice, 13th to 20th Centuries. In Literacy in the Persianate World (pp. 171-195). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Korkut, J., Morphology and lexicon-based machine translation of Ottoman Turkish to Modern Turkish.

- "The Ottoman Constitution, Promulgated the 7th Zilbridje, 1293 (11/23 December, 1876)". The American Journal of International Law. Cambridge University Press. 2 (4 (Supplement: Official Documents (Oct., 1908))): 367–387. 1908-10-01. doi:10.2307/2212668. JSTOR 2212668. S2CID 246006581.

ART. 18. Admission to public office has a condition — the knowledge of Turkish which is the official language of the State.

- Translation inclosed in dispatch No. 113 in the MS. Records, U.S. Department of State, dated December 26, 1876 (PDF version) - Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books 198. "In the Ottoman Empire, the scientific language for Muslims had been traditionally Arabic[...] or Ottoman Turkish. But this applied to the traditional sciences (ulûm)."

- Ihsanoglu, E. and Al-Hassani, S., 2004. The Madrasas of the Ottoman Empire. Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, Manchester. Mathematics Education in the Balkan Societies Up To the WWI.

- Panaite, V., 2019. Ottoman Law of War and Peace: The Ottoman Empire and Its Tribute-Payers from the North of the Danube. Brill.

- C. Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur (Leiden: Brill, 1937–1949), G II 583, S II 654.

- Ali, Mohammed Farid. "Principles of issuing fatwa (usul al-ifta) in the Hanafi legal school: an annotated translation, analysis and edition of sharh uqud rasm al-mufti of IbnAbidin Al-Shami." (2013).

- Taşkömür, H., 2019. Books on Islamic Jurisprudence, Schools of Law, and Biographies of Imams from the Hanafi School. In Treasures of Knowledge: An Inventory of the Ottoman Palace Library (1502/3-1503/4)(2 vols) (pp. 389-422). Brill.

- Peters, R., 2020. What Does It Mean to Be an Official Madhhab?: Hanafism and the Ottoman Empire. In Sharia, Justice and Legal Order (pp. 585-599). Brill.

- Yıldız, S.N., 2017. A Hanafi law manual in the vernacular: Devletoğlu Yūsuf Balıḳesrī’s Turkish verse adaptation of the Hidāya-Wiqāya textual tradition for the Ottoman Sultan Murad II (824/1424). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 80(2), pp.283-304.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 25 (PDF p. 27)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 34 (PDF p. 36)

- Strauss, Johann. "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire" (Chapter 7). In: Murphey, Rhoads (editor). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Routledge, 7 July 2016. (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books PT192.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 26 (PDF p. 28)

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books PT192 and PT193.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 25-26 (PDF p. 27-28)

- Chouinard, A.M., 2010. A Response to Tanzimat: Sultan Abdul Hamid II and Pan-Islamism. Inquiries Journal, 2(05).

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 21 (PDF p. 23)

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books PT 197.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 32 (PDF p. 34)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 29 (PDF p. 31)

- Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (2018-02-28). "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. - Volume 12 of Bamberger Orientstudien // Cited: p. 37

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 31-32 (PDF p. 33-34)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 33 (PDF p. 35)

- Trompoukis, Constantinos; Lascaratos, John (2003). "Greek Professors of the Medical School of Constantinople during a Period of Reformation (1839–76)". Journal of Medical Biography. 11 (4): 226–231. doi:10.1177/096777200301100411. PMID 14562157. S2CID 11201905. - First published November 1, 2003. - Cited: p. 226 (PDF p. 1/5).

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire" (ISBN 9781317118459), p. 121.

- Garnett, Lucy Mary Jane. Turkish Life in Town and Country. G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1904. p. 206.

- Kevorkian, Raymond (2008-06-03). "The Extermination of Ottoman Armenians by the Young Turk Regime (1915-1916)". Sciences Po. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

[...]these Turkish and Armenian elites —both francophone—[...]

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118459), p. 122.

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books PT192.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 26-27 (PDF p. 28-29)

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 27 (PDF p. 29)

- Turkish Yearbook of International Relations. Ankara Üniversitesi Diş Munasebetler Enstitüsü, 2000. (head book says 2000/2 Special Issue of Turkish-American Relations. Issue 31, Page 13. p. 13. "Chambre des Conseillers Légistes de la Porte as was their title in French, which had, after the Crimean War become the official working language of the Ottoman Foreign Ministry."

- Trompoukis, Constantinos; Lascaratos, John (2003). "Greek Professors of the Medical School of Constantinople during a Period of Reformation (1839–76)". Journal of Medical Biography. 11 (4): 226–231. doi:10.1177/096777200301100411. PMID 14562157. S2CID 11201905. - First published November 1, 2003. - Cited: p. 228 (PDF p. 3/5).

- Strauss, "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," (ISBN 9781317118442), Google Books PT194.

Further reading

- Strauss, Johann (November 1995). "The Millets and the Ottoman Language: The Contribution of Ottoman Greeks to Ottoman Letters (19th - 20th Centuries)". Die Welt des Islams. Brill. 35 (2): 189–249. doi:10.1163/1570060952597860. JSTOR 1571230.

- Strauss, Johann. "Diglossie dans le domaine ottoman. Évolution et péripéties d'une situation linguistique". In Vatin, Nicolas (ed.). Oral et écrit dans le monde turco-ottoman (in French). pp. 221–255. - Compare Revue du Monde Musulman et de la Méditerranée nos. 75-76, (1995).

- Fredj, Claire (16 May 2019). "Quelle langue pour quelle élite ? Le français dans le monde médical ottoman à Constantinople (1839-1914)". In Güneş Işıksel; Emmanuel Szurek (eds.). Turcs et Français. Histoire (in French). Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 73–98. ISBN 9782753559769.