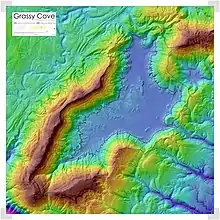

Grassy Cove

Grassy Cove is an enclosed valley in Cumberland County, Tennessee, United States. The valley is notable for its karst formations, which have been designated a National Natural Landmark. Grassy Cove is also home to a small unincorporated community.

Grassy Cove is located atop the Cumberland Plateau, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) east of Crossville and 5 miles (8.0 km) west of the plateau's Walden Ridge escarpment. The mountains that surround the cove are part of the southern fringe of the Cumberland Mountains. The cove is geologically related to the Sequatchie Valley, a large narrow valley stretching just opposite the mountains to the south. Tennessee State Route 68 passes through the northern part of Grassy Cove, providing the valley's only major road access.

Geology

Grassy Cove is walled in by 2,930-foot (890 m) Brady Mountain to the west, 2,930-foot (890 m) Bear Den Mountain on the east, and 2,828-foot (862 m) Black Mountain to the north. Brady and Bear Den both converge in a V-shaped formation to enclose the cove to the south. Just beyond this convergence, Hinch Mountain— the highest point in Cumberland County— rises to 3,048 feet (929 m). The southern slopes of Hinch descend drastically to the Sequatchie Valley. The elevation of Grassy Cove is just over 1,500 feet (460 m), whereas the elevation of the Sequatchie Valley is roughly 900 feet (270 m).

Both the Sequatchie Valley and Grassy Cove were part of an anticline that formed as rock strata were bent upward by thrust faulting to form a large ridge during the Paleozoic era (appx. 250 million years ago). During the Mesozoic era, continued erosion along this ridge exposed its younger, more soluble Mississippian aged limestone layers. Over subsequent millennia, the limestone dissolved, forming a series of sinkholes that eventually coalesced to create the Sequatchie Valley. Grassy Cove is one such sinkhole that has yet to coalesce with the rest of the Sequatchie Valley.[1]

Grassy Cove is drained entirely by underground streams. The valley's main stream, Grassy Cove Creek, flows northward across the cove before dropping into Mill Cave on the slopes of Brady Mountain. Dye traces indicate that it flows south through a series of caves before reemerging at the head of the Sequatchie Valley[2] at Devilstep Hollow Cave, where it forms the headwaters of the Sequatchie River.[3] Grassy Cove Saltpeter Cave, located on the eastern slope of Brady Mountain, is the sixteenth longest cave in Tennessee[4] and one of the 100 longest caves in the United States.[5] Other caves in the cove include Windlass Cave, Bristow Cave, Mill Cave, Run to the Mill Cave, and Milksick Cave.

Sinkhole dimensions:[6]

- Watershed Area: 33.1770 km2 (12.8097 sq mi)

- Watershed Perimeter: 42.1524 km (26.1923 mi)

- Sinkhole Area: 13.3112 km2 (5.1395 sq mi)

- Sinkhole Perimeter: 35.7192 km (22.1949 mi)

- Sinkhole Depth: 39.97 m (131.1 ft)

- Sinkhole Volume: 37,736,946 m3 (1.3326677×109 cu ft)

- Sinkhole Minimum Elevation: 467.27 m (1,533.0 ft) at 35.856046, -84.927142

- Sinkhole Maximum Elevation: 507.24 m (1,664.2 ft)

- Sinkhole Major Axis: 7.6736 km (4.7682 mi)

- Sinkhole Minor Axis: 4.3629 km (2.7110 mi)

- Sinkhole Declination: 30.8 degrees

- Pour Point: 35.826952, -84.90215

History

Although no extensive archaeological work has been conducted in Grassy Cove, early farmers found projectile points and other prehistoric artifacts when plowing fields, suggesting that Native Americans were living in the cove during prehistoric times.[7] Also, early 19th-century settlers reportedly found the cove bottom cleared and containing only high grass upon their arrival.[8] Hence the name: Grassy Cove.

The first settlers arrived in Grassy Cove in 1801. This early caravan consisted primarily of families from Fluvanna County, Virginia. In 1803, they completed a log church and formed the Grassy Cove United Methodist Church, one of the first congregations in the Cumberland Plateau region. Prominent early settlers included Conrad Kemmer, a Revolutionary War veteran who arrived in 1808, and Weatherston Greer, who arrived around 1830. Greer set up the first post office in the cove, operated a sawmill and gristmill, and owned large tracts of land in the cove until the U.S. Civil War. Kemmer's descendants own much of the land in Grassy Cove today.[9]

During both the War of 1812 and the Civil War, Grassy Cove's caves were an invaluable source of saltpeter, which was used in the manufacture of gunpowder. William Kelly mined saltpeter in Grassy cove Saltpeter Cave in 1812, according to a manuscript written by Richard Green Waterhouse.[10] According to a local legend, the body of a Confederate soldier (in full uniform) was found in a petrified state in one of the caves shortly after the war. When no one claimed the body, it was buried in the Grassy Cove Methodist Cemetery. Several residents claimed to have seen the soldier's ghost in the church, however, and when church attendance began to drop as a result, the soldier's body was disinterred and reburied in an undisclosed location.[11][12]

Cumberland Trail

In 1998, the state of Tennessee established the Justin P. Wilson Cumberland Trail State Park, a linear park that will eventually encompass the 300-mile (480 km) Cumberland Trail (the trail is still currently under construction). The trail now includes the 15-mile (24 km) "Grassy Cove Segment" that traverses the crests of Black Mountain and Brady Mountain. This segment of the trail will connect the Crab Orchard Segment (still being planned) with the Stinging Fork segment (partially completed) to the south.[13]

Further reading

- Larry E. Matthews, Caves of Grassy Cove, National Speleological Society, August 2014. ISBN 978-1-879961-49-4

References

- Harry Moore, A Geologic Trip Across Tennessee by Interstate 40 (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), 69-70.

- Crawford, N.C. (1989). "The karst hydrogeology of the Cumberland Plateau Escarpment of Tennessee (Grassy Cove area)". TN Div. of Geology, Rept. of Investigation #44. 2: 41.

- Moore, 237.

- Tennessee Cave Survey, "Data Disk." 30 September 2017. Retrieved: 21 December 2017.

- Bob Gulden, "NSS U.S.A Long Cave List." 09 August 2017. Retrieved: 21 December 2017.

- Dunigan/Sutherland, Tennessee sinkholes 2013

- The WPA Guide to Tennessee (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1986), 500. Originally compiled by the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Project Administration as Tennessee: A Guide to the State, and published in 1939.

- Helen Bullard and Joseph Krechniak, Cumberland County's First Hundred Years (Crossville, Tenn.: Centennial Committee, 1956), 126.

- Bullard and Krechniak, 126-129.

- Matthews, Larry (2014). Caves of Grassy Cove. National Speleological Society. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-879961-49-4.

- Bullard and Krechniak, 128-129.

- Information obtained from plaque entitled "Legend of Grassy Cove's Petrified Soldier" at the Grassy Cove Community Center, 29 March 2008.

- Tennessee Trail Association, "Cumberland Trail - Grassy Cove Segment Archived 2008-05-13 at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved: 24 June 2008.

External links

- Grassy Cove Karst Area Archived 2011-10-16 at the Wayback Machine — National Park Service website

- Tennessee sinkholes