Gravity turn

A gravity turn or zero-lift turn is a maneuver used in launching a spacecraft into, or descending from, an orbit around a celestial body such as a planet or a moon. It is a trajectory optimization that uses gravity to steer the vehicle onto its desired trajectory. It offers two main advantages over a trajectory controlled solely through the vehicle's own thrust. First, the thrust is not used to change the spacecraft's direction, so more of it is used to accelerate the vehicle into orbit. Second, and more importantly, during the initial ascent phase the vehicle can maintain low or even zero angle of attack. This minimizes transverse aerodynamic stress on the launch vehicle, allowing for a lighter launch vehicle.[1][2]

The term gravity turn can also refer to the use of a planet's gravity to change a spacecraft's direction in situations other than entering or leaving the orbit.[3] When used in this context, it is similar to a gravitational slingshot; the difference is that a gravitational slingshot often increases or decreases spacecraft velocity and changes direction, while the gravity turn only changes direction.

Launch procedure

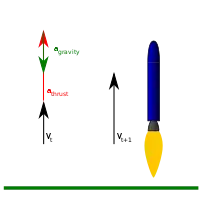

Vertical climb

A gravity turn is commonly used with rocket powered vehicles that launch vertically, like the Space Shuttle. The rocket begins by flying straight up, gaining both vertical speed and altitude. During this portion of the launch, gravity acts directly against the thrust of the rocket, lowering its vertical acceleration. Losses associated with this slowing are known as gravity drag, and can be minimized by executing the next phase of the launch, the pitchover maneuver or roll program, as soon as possible. The pitchover should also be carried out while the vertical velocity is small to avoid large aerodynamic loads on the vehicle during the maneuver.[1]

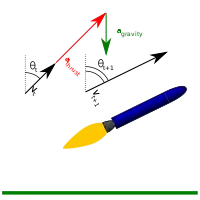

The pitchover maneuver consists of the rocket gimbaling its engine slightly to direct some of its thrust to one side. This force creates a net torque on the ship, turning it so that it no longer points vertically. The pitchover angle varies with the launch vehicle and is included in the rocket's inertial guidance system.[1] For some vehicles it is only a few degrees, while other vehicles use relatively large angles (a few tens of degrees). After the pitchover is complete, the engines are reset to point straight down the axis of the rocket again. This small steering maneuver is the only time during an ideal gravity turn ascent that thrust must be used for purposes of steering. The pitchover maneuver serves two purposes. First, it turns the rocket slightly so that its flight path is no longer vertical, and second, it places the rocket on the correct heading for its ascent to orbit. After the pitchover, the rocket's angle of attack is adjusted to zero for the remainder of its climb to orbit. This zeroing of the angle of attack reduces lateral aerodynamic loads and produces negligible lift force during the ascent.[1]

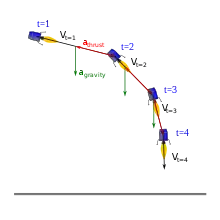

Downrange acceleration

After the pitchover, the rocket's flight path is no longer completely vertical, so gravity acts to turn the flight path back towards the ground. If the rocket were not producing thrust, the flight path would be a simple ellipse like a thrown ball (it is a common mistake to think it is a parabola: this is only true if it is assumed that the Earth is flat, and gravity always points in the same direction, which is a good approximation for short distances), leveling off and then falling back to the ground. The rocket is producing thrust though, and rather than leveling off and then descending again, by the time the rocket levels off, it has gained sufficient altitude and velocity to place it in a stable orbit.

If the rocket is a multi-stage system where stages fire sequentially, the rocket's ascent burn may not be continuous. Some time must be allowed for stage separation and engine ignition between each successive stage, but some rocket designs call for extra free-flight time between stages. This is particularly useful in very high thrust rockets, where if the engines were fired continuously, the rocket would run out of fuel before leveling off and reaching a stable orbit above the atmosphere.[2] The technique is also useful when launching from a planet with a thick atmosphere, such as the Earth. Because gravity turns the flight path during free flight, the rocket can use a smaller initial pitchover angle, giving it higher vertical velocity, and taking it out of the atmosphere more quickly. This reduces both aerodynamic drag as well as aerodynamic stress during launch. Then later during the flight the rocket coasts between stage firings, allowing it to level off above the atmosphere, so when the engine fires again, at zero angle of attack, the thrust accelerates the ship horizontally, inserting it into orbit.

Descent and landing procedure

Because heat shields and parachutes cannot be used to land on an airless body such as the Moon, a powered descent with a gravity turn is a good alternative. The Apollo Lunar Module used a slightly modified gravity turn to land from lunar orbit. This was essentially a launch in reverse except that a landing spacecraft is lightest at the surface while a spacecraft being launched is heaviest at the surface. A computer program called Lander that simulated gravity turn landings applied this concept by simulating a gravity turn launch with a negative mass flow rate, i.e. the propellant tanks filled during the rocket burn.[4] The idea of using a gravity turn maneuver to land a vehicle was originally developed for the Lunar Surveyor landings, although Surveyor made a direct approach to the surface without first going into lunar orbit.[5]

Deorbit and entry

The vehicle begins by orienting for a retrograde burn to reduce its orbital velocity, lowering its point of periapsis to near the surface of the body to be landed on. If the craft is landing on a planet with an atmosphere such as Mars the deorbit burn will only lower periapsis into the upper layers of the atmosphere, rather than just above the surface as on an airless body. After the deorbit burn is complete the vehicle can either coast until it is nearer to its landing site or continue firing its engine while maintaining zero angle of attack. For a planet with an atmosphere the coast portion of the trip includes entry through the atmosphere as well.

After the coast and possible entry the vehicle jettisons any no longer necessary heat shields and/or parachutes in preparation for the final landing burn. If the atmosphere is thick enough it can be used to slow the vehicle a considerable amount, thus saving on fuel. In this case a gravity turn is not the optimal entry trajectory but it does allow for approximation of the true delta-v required.[6] In the case where there is no atmosphere however, the landing vehicle must provide the full delta-v necessary to land safely on the surface.

Landing

If it is not already properly oriented, the vehicle lines up its engines to fire directly opposite its current surface velocity vector, which at this point is either parallel to the ground or only slightly vertical, as shown to the left. The vehicle then fires its landing engine to slow down for landing. As the vehicle loses horizontal velocity the gravity of the body to be landed on will begin pulling the trajectory closer and closer to a vertical descent. In an ideal maneuver on a perfectly spherical body the vehicle could reach zero horizontal velocity, zero vertical velocity, and zero altitude all at the same moment, landing safely on the surface (if the body is not rotating; else the horizontal velocity shall be made equal to the one of the body at the considered latitude). However, due to rocks and uneven surface terrain the vehicle usually picks up a few degrees of angle of attack near the end of the maneuver to zero its horizontal velocity just above the surface. This process is the mirror image of the pitch over maneuver used in the launch procedure and allows the vehicle to hover straight down, landing gently on the surface.

Guidance and control

The steering of a rocket's course during its flight is divided into two separate components; control, the ability to point the rocket in a desired direction, and guidance, the determination of what direction a rocket should be pointed to reach a given target. The desired target can either be a location on the ground, as in the case of a ballistic missile, or a particular orbit, as in the case of a launch vehicle.

Launch

The gravity turn trajectory is most commonly used during early ascent. The guidance program is a precalculated lookup table of pitch vs time. Control is done with engine gimballing and/or aerodynamic control surfaces. The pitch program maintains a zero angle of attack (the definition of a gravity turn) until the vacuum of space is reached, thus minimizing lateral aerodynamic loads on the vehicle. (Excessive aerodynamic loads can quickly destroy the vehicle.) Although the preprogrammed pitch schedule is adequate for some applications, an adaptive inertial guidance system that determines location, orientation and velocity with accelerometers and gyroscopes, is almost always employed on modern rockets. The British satellite launcher Black Arrow was an example of a rocket that flew a preprogrammed pitch schedule, making no attempt to correct for errors in its trajectory, while the Apollo-Saturn rockets used "closed loop" inertial guidance after the gravity turn through the atmosphere.[7]

The initial pitch program is an open-loop system subject to errors from winds, thrust variations, etc. To maintain zero angle of attack during atmospheric flight, these errors are not corrected until reaching space.[8] Then a more sophisticated closed-loop guidance program can take over to correct trajectory deviations and attain the desired orbit. In the Apollo missions, the transition to closed-loop guidance took place early in second stage flight after maintaining a fixed inertial attitude while jettisoning the first stage and interstage ring.[8] Because the upper stages of a rocket operate in a near vacuum, fins are ineffective. Steering relies entirely on engine gimballing and a reaction control system.

Landing

To serve as an example of how the gravity turn can be used for a powered landing, an Apollo type lander on an airless body will be assumed. The lander begins in a circular orbit docked to the command module. After separation from the command module the lander performs a retrograde burn to lower its periapsis to just above the surface. It then coasts to periapsis where the engine is restarted to perform the gravity turn descent. It has been shown that in this situation guidance can be achieved by maintaining a constant angle between the thrust vector and the line of sight to the orbiting command module.[9] This simple guidance algorithm builds on a previous study which investigated the use of various visual guidance cues including the uprange horizon, the downrange horizon, the desired landing site, and the orbiting command module.[10] The study concluded that using the command module provides the best visual reference, as it maintains a near constant visual separation from an ideal gravity turn until the landing is almost complete. Because the vehicle is landing in a vacuum, aerodynamic control surfaces are useless. Therefore, a system such as a gimballing main engine, a reaction control system, or possibly a control moment gyroscope must be used for attitude control.

Limitations

Although gravity turn trajectories use minimal steering thrust they are not always the most efficient possible launch or landing procedure. Several things can affect the gravity turn procedure making it less efficient or even impossible due to the design limitations of the launch vehicle. A brief summary of factors affecting the turn is given below.

- Atmosphere — In order to minimize gravity drag the vehicle should begin gaining horizontal speed as soon as possible. On an airless body such as the Moon this presents no problem, however on a planet with a dense atmosphere this is not possible. A trade-off exists between flying higher before starting downrange acceleration, thus increasing gravity drag losses; or starting downrange acceleration earlier, reducing gravity drag but increasing the aerodynamic drag experienced during launch.

- Maximum dynamic pressure — Another effect related to the planet's atmosphere is the maximum dynamic pressure exerted on the launch vehicle during the launch. Dynamic pressure is related to both the atmospheric density and the vehicle's speed through the atmosphere. Just after liftoff the vehicle is gaining speed and increasing dynamic pressure faster than the reduction in atmospheric density can decrease the dynamic pressure. This causes the dynamic pressure exerted on the vehicle to increase until the two rates are equal. This is known as the point of maximum dynamic pressure (abbreviated "max Q"), and the launch vehicle must be built to withstand this amount of stress during launch. As before a trade off exists between gravity drag from flying higher first to avoid the thicker atmosphere when accelerating; or accelerating more at lower altitude, resulting in a heavier launch vehicle because of a higher maximum dynamic pressure experienced on launch.

- Maximum engine thrust — The maximum thrust the rocket engine can produce affects several aspects of the gravity turn procedure. Firstly, before the pitch over maneuver the vehicle must be capable of not only overcoming the force of gravity but accelerating upwards. The more acceleration the vehicle has beyond the acceleration of gravity the quicker vertical speed can be obtained allowing for lower gravity drag in the initial launch phase. When the pitch over is executed the vehicle begins its downrange acceleration phase; engine thrust affects this phase as well. Higher thrust allows for a faster acceleration to orbital velocity as well. By reducing this time the rocket can level off sooner; further reducing gravity drag losses. Although higher thrust can make the launch more efficient, accelerating too much low in the atmosphere increases the maximum dynamic pressure. This can be alleviated by throttling the engines back during the beginning of downrange acceleration until the vehicle has climbed higher. However, with solid fuel rockets this may not be possible.

- Maximum tolerable payload acceleration — Another limitation related to engine thrust is the maximum acceleration that can be safely sustained by the crew and/or the payload. Near main engine cut off (MECO), when the launch vehicle has consumed most of its fuel, the vehicle will be much lighter than it was at launch. If the engines are still producing the same amount of thrust, the acceleration will grow as a result of the decreasing vehicle mass. If this acceleration is not kept in check by throttling back the engines, injury to the crew or damage to the payload could occur. This forces the vehicle to spend more time gaining horizontal velocity, increasing gravity drag.

Use in orbital redirection

For spacecraft missions where large changes in the direction of flight are necessary, direct propulsion by the spacecraft may not be feasible due to the large delta-v requirement. In these cases it may be possible to perform a flyby of a nearby planet or moon, using its gravitational attraction to alter the ship's direction of flight. Although this maneuver is very similar to the gravitational slingshot it differs in that a slingshot often implies a change in both speed and direction whereas the gravity turn only changes the direction of flight.

A variant of this maneuver, the free return trajectory allows the spacecraft to depart from a planet, circle another planet once, and return to the starting planet using propulsion only during the initial departure burn. Although in theory it is possible to execute a perfect free return trajectory, in practice small correction burns are often necessary during the flight. Even though it does not require a burn for the return trip, other return trajectory types, such as an aerodynamic turn, can result in a lower total delta-v for the mission.[3]

Use in spaceflight

Many spaceflight missions have utilized the gravity turn, either directly or in a modified form, to carry out their missions. What follows is a short list of various mission that have used this procedure.

- Surveyor program — A precursor to the Apollo Program, the Surveyor Program's primary mission objective was to develop the ability to perform soft landings on the surface of the Moon, through the use of an automated descent and landing program built into the lander.[11] Although the landing procedure can be classified as a gravity turn descent, it differs from the technique most commonly employed in that it was shot from the Earth directly to the lunar surface, rather than first orbiting the Moon as the Apollo landers did. Because of this the descent path was nearly vertical, although some "turning" was done by gravity during the landing.[12]

- Apollo program — Launches of the Saturn V rocket during the Apollo program were carried out using a gravity turn in order to minimize lateral stress on the rocket. At the other end of their journey, the lunar landers utilized a gravity turn landing and ascent from the Moon.

Mathematical description

The simplest case of the gravity turn trajectory is that which describes a point mass vehicle, in a uniform gravitational field, neglecting air resistance. The thrust force is a vector whose magnitude is a function of time and whose direction can be varied at will. Under these assumptions the differential equation of motion is given by:

Here is a unit vector in the vertical direction and is the instantaneous vehicle mass. By constraining the thrust vector to point parallel to the velocity and separating the equation of motion into components parallel to and those perpendicular to we arrive at the following system:[13]

Here the current thrust to weight ratio has been denoted by and the current angle between the velocity vector and the vertical by . This results in a coupled system of equations which can be integrated to obtain the trajectory. However, for all but the simplest case of constant over the entire flight, the equations cannot be solved analytically and must be integrated numerically.

References

- Glasstone, Samuel (1965). Sourcebook on the Space Sciences. D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. pp. 209 or §4.97.

- Callaway, David W. (March 2004). "Coplanar Air Launch with Gravity-Turn Launch Trajectories" (PDF). Masters Thesis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-28.

- Luidens, Roger W. (1964). "Mars Nonstop Round-Trip Trajectories". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. 2 (2): 368–370. Bibcode:1964AIAAJ...2..368L. doi:10.2514/3.2330. hdl:2060/19640008410.

- Eagle Engineering, Inc (September 30, 1988). "Lander Program Manual". NASA Contract Number NAS9-17878. EEI Report 88-195. hdl:2060/19890005786.

- "Boeing Satellite Development: Surveyor Mission Overview". boeing.com. Boeing. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Braun, Robert D.; Manning, Robert M. (2006). Mars Exploration Entry, Descent and Landing Challenges (PDF). IEEE Aerospace Conference. p. 1. doi:10.1109/AERO.2006.1655790. ISBN 0-7803-9545-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2006.

- "Launch vehicle handbook. Compilation of launch vehicle performance and weight data for preliminary planning purposes". NASA Technical Memorandum. TM 74948. September 1961.

- "Apollo systems description. Volume 2 - Saturn launch vehicles". NASA Technical Memorandum. TM X-881. February 1964. hdl:2060/19710065502.

- Barker, L. Keith (December 1964). "Application of a Lunar Landing Technique for Landing from an Elliptic Orbit Established by a Hohmann Transfer". NASA Technical Note. TN D-2520. hdl:2060/19650002270.

- Barker, L. Keith; Queijo, M. J. (June 1964). "A Technique for Thrust-Vector Orientation During Manual Control of Lunar Landings from a Synchronous Orbit". NASA Technical Note. TN D-2298. hdl:2060/19640013320.

- Thurman, Sam W. (February 2004). Surveyor Spacecraft Automatic Landing System. 27th Annual AAS Guidance and Control Conference. Archived from the original on 2008-02-27.

- Thurman, Sam W. (2004). Surveyor spacecraft automatic landing system (Report). NASA. p. 6. hdl:2014/38026. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- Culler, Glen J.; Fried, Burton D. (June 1957). "Universal Gravity Turn Trajectories". Journal of Applied Physics. 28 (6): 672–676. Bibcode:1957JAP....28..672C. doi:10.1063/1.1722828.