Great Siege Tunnels

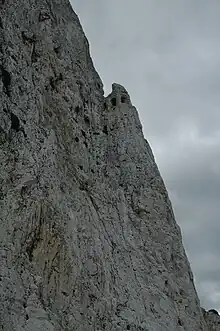

The Great Siege Tunnels in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar, also known as the Upper Galleries, are a series of tunnels inside the northern end of the Rock of Gibraltar. They were dug out from the solid limestone by the British during the Great Siege of Gibraltar of the late 18th century.

| Great Siege Tunnels | |

|---|---|

Upper Galleries | |

| Part of Fortifications of Gibraltar | |

| Northern end of the Rock of Gibraltar | |

Great Siege Tunnels in the Rock of Gibraltar. | |

Great Siege Tunnels | |

| Coordinates | 36.145153°N 5.345047°W |

| Type | Tunnel |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Government of Gibraltar |

| Controlled by | Gibraltar Tourist Board |

| Open to the public | Partially open |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1780 |

| Built by | Soldier Artificer Company |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | Great Siege of Gibraltar |

History

The Great Siege of Gibraltar was an attempt by France and Spain to capture Gibraltar from Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. Lasting from July 1779 to February 1783, it was the fourteenth and final siege of Gibraltar. During the siege, British and Spanish forces faced each other across an approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) wide stretch of the marshy open ground that forms the isthmus immediately to the north of the Rock of Gibraltar. The British lines blocked access to the City and the western side of the Rock, while the eastern side of the Rock was inaccessible because of its steep terrain.[1] Gun batteries were placed in a series of galleries on the north face of the Rock, providing overlapping fields of fire so that infantry attacks would come under heavy fire throughout their advance.[2]

The impetus for the construction of the tunnels came from the garrison's need to cover a blind angle on the north-east side of the Rock. The only solution found to cover that angle was via a gun mounted on a spur of rock known as The Notch. There was no possibility of building a path there due to the vertical cliff face, so Sergeant-Major Henry Ince of the Military Artificers suggested digging a tunnel to reach it. His plan was approved and construction work began on 25 May 1782.[3]

Construction and design

The work was carried out by hand, mainly using sledgehammers and crowbars, aided by gunpowder blasts. The work proceeded slowly at first; it took thirteen men five weeks to dig a tunnel with a length of 82 feet (25 m). The diggers were hindered by fumes and dust from the frequent blasting, so it was decided to blast a horizontal shaft to improve the tunnels' ventilation. This was done and was found to have had an unexpected side benefit. Colonel John Drinkwater Bethune, who wrote an account of the siege in 1785, described how this came about:

[T]he mine was loaded with an unusual quantity of powder, and the explosion was so amazingly loud, that almost the whole of the Enemy's camp turned out at the report: but what must their surprise be, when they observed where the smoke issued! – The original intention of this opening, was to communicate air to the workmen, who before were almost suffocated with the smoke which remained after blowing the different mines; but, on examining the aperture more closely, an idea was conceived of mounting a gun to bear on all the Enemy's batteries, excepting Fort Barbara: accordingly orders were given to enlarge the inner part [of the tunnel] for the recoil; and when finished, a twenty-four-pounder was mounted.[4]

Work progressed fairly rapidly thereafter, though it did not entirely go to plan, with several false starts in direction in the latter part of 1782. One tunnel drive was determined to be too far from the outer face of the Rock and another too close to it. A consistent direction was eventually found, and by the end of the fourth siege embrasures had been blasted overlooking the Spanish lines. Total construction length of the tunnels by the end of 1783 was approximately 908 feet (277 m). When excavations reached The Notch in the summer of 1783 it was decided that instead of pursuing the original idea of mounting a single gun on top of it, The Notch would be hollowed out into a broad chamber that the diggers named St. George's Hall and that was later equipped with seven guns.[3]

By the end of the initial phase of tunnelling, five galleries had been excavated: Windsor Gallery, King's And Queen's Lines, St. George's Hall, and Cornwallis Chamber. The Windsor Gallery was the first part of the tunnel system, and four guns were mounted there. St. George's Hall is the largest of the original galleries. The embrasures can be seen on the slopes of the Rock when approaching Gibraltar from land and sea.[5]

Originally the embrasures were fitted with mantlets or curtains of woven ropes; the rails on which they were supported can still be seen. These protected the guns and gunners from enemy fire and prevented sparks and smoke blowing back into the embrasures.[3] As an additional safety measure, each cannon was isolated with a wet cloth hanging above it from a rope, to prevent the sparks from igniting the remaining gunpowder.[5]

Later history of the tunnels

General George Augustus Eliott had offered a reward to anyone who would invent a method to get cannons to the other side of the Rock. Although it is unknown whether Sergeant Major Ince ever got this reward,[5] he received a plot of land on the Upper Rock, which is still called Ince's Farm. He was later given a valuable horse. Ince's troops, who were known at the time as Soldier Artificers, founded the Soldier Artificer Company in Gibraltar in 1772, which later became the Corps of Royal Engineers.[6]

During the 19th century the original cannon were replaced with more modern 64-pounder rifled muzzle loaders on iron carriages, some of which can still be seen in the tunnels.[7] Although Ince's galleries remained little changed, the work that he started was hugely expanded in the years after the siege and new tunnels were built to connect to the first galleries. By 1790 around 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of tunnels had been constructed inside the Rock.[6]

The Second World War led to another great wave of tunnelling as work was undertaken to enable the Rock to house a garrison of 16,000 men with water, food, ammunition and fuel supplies sufficient to last a year under siege.[8] The Great Siege Tunnels were reused during the war; although it is uncertain exactly how they were used, it appears that they may have housed one of the generators used to power Gibraltar's searchlights, as a concrete mounting pad of the requisite dimensions was installed in one of the embrasures. The Great Siege Tunnels were extended in two directions during the war, with a long straight extension called the Holyland Tunnel continuing through to the east side of the Rock, so named because it points in the direction of Jerusalem; and a staircase dug to link the tunnels with other Second World War tunnels lower down, known as the Middle Galleries. However, the methods by which the Second World War tunnels were hastily excavated have meant that – unlike the original 18th century tunnels – they have crumbled rapidly and now can not be safely accessed.[9]

The Great Siege Tunnels can today be accessed as part of the Upper Rock Nature Reserve.

References

- Chartrand, Rene (2006). Gibraltar 1779 - 1783:The Great Siege. Osprey Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 9781841769776.

- Hills, George (1974). Rock of Contention: A history of Gibraltar. London: Robert Hale & Company. p. 333. ISBN 0-7091-4352-4.

- Fa, Darren; Finlayson, Clive (2006). The Fortifications of Gibraltar. Osprey Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 1-84603-016-1.

- Drinkwater, John (1785). A History of the Late Siege of Gibraltar. T. Spilsbury. pp. 247–8.

- Great Siege Tunnels Gibraltar Travel Guide

- Chartrand, p. 24

- "History of the Tunnels". Great Siege Tunnels, Gibraltar.

- Finlayson, p. 47

- "The Tunnels in World War II". Great Siege Tunnels, Gibraltar