Grimsby and Immingham Electric Railway

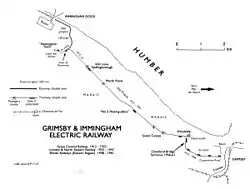

The Grimsby & Immingham Electric Railway (G&IER) was an electric light railway, primarily for passenger traffic, linking Great Grimsby with the Port of Immingham in Lincolnshire, England. The line was built by the Great Central Railway (GCR), was absorbed by the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) in 1923, and became part of the Eastern Region of British Railways. It ran mainly on reserved track.

The Grimsby and Immingham Light Railway | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Grimsby |

| Locale | North East Lincolnshire England |

| Dates of operation | 1912–1961 |

| Successor | Abandoned |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 7 miles (11 km) |

Grimsby and Immingham Electric Railway |

|---|

History

The origin of the line lay in the decision of the Great Central Railway (GCR) to build a vast new docks complex on the marshlands of the south bank of the Humber near the small settlement of Immingham. The GCR reached agreement for the purchase of the land required and presented two Bills in Parliament of which the second was enacted as the Humber Commercial Railway and Dock Act 1904. A number of railways were authorised in connection with the construction and operation of the dock estate, comprising a new main-line railway approaching from Ulceby in the south (the Humber Commercial Railway); a branch from Goxhill in the west, facilitating services to and from New Holland and the Humber ferries (the Barton and Immingham Light Railway); and a direct link towards Grimsby (the Grimsby District Light Railway, GDLR, for which light railway powers were granted on 15 January 1906).[1][2] Dock operation was labour-intensive and the GCR recognised that it would need to operate a passenger service to bring in dockers from neighbouring towns, principally the fishing port of Great Grimsby about seven miles east. The company also built a large locomotive depot at Immingham, which required workers’ transport. These enactments and considerations were the starting point of the G&IER.

To facilitate construction of the docks the GDLR was initially built from the Grimsby direction as a contractors’ railway and the GCR ran a steam-hauled workmen's service on this from 3 January 1910.[3] The GCR had two reasons for proposing an electric tramway in addition to this light railway. (Legally the G&IER would form part of the GDLR, although there was no physical connection between them). They had developed a major power generating plant at the Docks, which used electricity extensively for crane and lock operation. This could economically supply the tramway, and did so until 1957. Secondly they envisaged on-street operation in Grimsby itself, extending the area served and facilitating direct connexion with the existing Grimsby and Cleethorpes tramways. The GCR's 1906 light railway order included a 1½ mile street tramway between Corporation Bridge and Cleveland Bridge in Grimsby, and a private right-of way alongside the existing GDLR between Cleveland Bridge and Immingham Dock.[1]

The network

The electric line opened from Grimsby as far as Immingham Town on the eastern fringe of the dock estate on Wednesday 15 May 1912. It was extended about a mile into the estate on 17 November 1913, terminating at the landward end of the Eastern Jetty, a short walk from the Immingham Dock station of the Barton and Immingham Light Railway. For reasons not fully understood the 1913 extension joined the existing line at Immingham Town by a trailing junction, necessitating a reversal on all through journeys.[4] A short spur was built in 1914 from Immingham Town terminus to Queens Road nearer Immingham Village, but this was never opened to normal traffic,[5] possibly because of the onset of the First World War. The G&IER from Corporation Bridge to Immingham Town was single track with passing loops of a standard length of 110 yards (100 m).[6][7] The 1913 extension from Immingham Town to Immingham Dock was double track alongside the road,[8] except where it shared the road as it crossed "Tramcar Bridge" east of Immingham Town.[9][10] There were originally eight intermediate loops on the cross-country Pyewipe – Immingham Town section,[11] numbered in sequence from Pyewipe, although most stops also had names. Four of the loops were removed in 1917, the track being used for war purposes. There were three[12] or possibly four[11] loops on the street section in Grimsby.[13]

There were small waiting rooms and offices at Corporation Bridge and Immingham Dock termini. A temporary structure was erected at Cleveland Bridge after the line was cut back in 1956.

Although the Grimsby terminus at Corporation Bridge was only a few yards from the municipal tramway tracks in Victoria Street the intervening bridge was not rebuilt until 1928, and by then Grimsby's trams were giving way to trolleybuses and the connecting tramway was never built. The G&IER did, however, operate a local tram service on its street section between Corporation Bridge and Cleveland Bridge for two years 1928 – 1930.[14]

Power supply

The line was electrified at 500 volts direct current, with power supplied through simple trolley wire supported either from span wires between steel poles (concrete poles between Immingham Town and Immingham Dock), or from side brackets. Current collection was by trolley poles.[15] A separate high-tension feeder on wooden poles ran alongside the line, providing current for dock operation in Grimsby.[16][1][17]

Traction power was at first supplied by two substations, transformed and converted from a 6,600 volt ac main fed from the docks generating station.[18] The first was built three miles from Immingham by Siemens Brothers. Two Westinghouse 250 kW rotary converters produced 500 V DC for the trams. Traction feeders were installed every half-mile. The substation itself was a redbrick construction, built by Dennis Gill & Sons of Doncaster for £507. The 1913 extension was supplied by a substation within the dock estate. The second substation, continuously staffed, was also built by Gill, for £707, next to the car sheds at Pyewipe. It contained three 250 kW Westinghouse rotary converters. One converter was used for lighting, one for traction and the third as a standby. From 26 November 1957 high tension power was drawn from the National Grid and the dock power station was closed down.[19]

Pyewipe car sheds

The sheds were formally known as "Cleveland Bridge Works"[20] but rarely so in practice, gaining the name "Pyewipe" from nearby marshes and road on the edge of Grimsby. They serviced all the trams.[21] They did not house the cars,[22][23][24] which, unusually for British trams, spent all their life outdoors, only entering the workshop when repairs were needed.[25] The workshop had the capacity to hold three trams on two tracks. It also housed a machine shop, paint shop and store. Until 1940 cars were periodically sent to Dukinfield carriage works for major repair. The second-hand Gateshead cars (see below) were overhauled at York before entering service.[26] The G&IER had no physical connection with the national network apart from a right-angled flat crossing with a siding near Corporation Bridge which was unusable for interchange traffic. The line closed long before the days when putting a tram on the back of a low-loader to take it to Manchester would be normal. When heavy repairs were needed or new trams were delivered they were craned between tramway metals and the GDLR which ran past the shed.[27]

Rolling stock

The line was originally equipped with eight unique bogie single-decked tramcars, designed by the GCR and built by Brush,[28][29][30] to which four more were added in 1913, and a further four (built by the GCR themselves) in 1914. Four of the original cars were short-bodied,[31][32][33] intended for through operation onto the Grimsby street tramways, but the majority of the fleet, at 43 feet 8 inches (16.51 metres) overall length, were by far the largest British trams until modern times: with 72 seats, they had a larger capacity than many contemporary double-deckers.[13] Although relatively progressive for the period, the cars lacked what were already becoming refinements in Europe: they used trolley-poles not pantograph collectors and they lacked any means of coupled or multiple-unit operation, thus failing to exploit the main labour-saving qualities of modern tramcars. The cars had wooden swing-back lateral seats[34] throughout their lives. They had a central luggage and goods compartment (known locally as "The Horse Box") and handled milk, produce, and small consignments. All remaining cars were painted in BR ‘electric green’ after 1951,[35] replacing LNER brown livery.

After 1945 Grimsby Corporation promoted a 200-acre industrial estate west of the town and near the G&IER, and in the absence of any direct road, workers at the new factories also relied on the tramway. To handle the extra passenger traffic British Railways acquired three single-decked bogie trams from Newcastle Corporation Transport in 1948 (the only cars on the line to have upholstered seats)[36][37][33][38][39][40][41][42] and a further nineteen were bought in 1951 from the Gateshead and District Tramways Company, which had just ceased operation (one was dropped whilst being craned into the shed during delivery and destroyed, so only eighteen entered service).[33][43] The ex-Gateshead cars had wooden longitudinal bench seats, allowing more standing room down the vehicles' centres.[44][39] By then the four ‘short’ trams had been withdrawn, though one of them, No.5, was converted into a works car. The ex-Newcastle trams and four GCR-type cars were withdrawn by 1953, the body of one of the latter - No.10 - was used as a shed at Pyewipe depot.[45] The undertaking had a maximum of 25 passenger trams in operation by 1954 out of 37 supplied. One of the Gateshead cars was adapted as a works vehicle, at which point the earlier works car - No. 5 - was scrapped. The new works car was given District Engineer's number DE320224,[46] probably the highest ever carried by a tram anywhere.[47][48][49]

Operations

Because of the particular needs of the workforce the G&IER was unique amongst British tramways in operating a service throughout every day and night for most of its existence. Normally service during the day was every 20 or 30 minutes with less frequent trams overnight and extras at peak times.[50] Because traffic was very heavily peaked, departures at shift-change times often took the form of convoys of up to seven trams.[51] Running time was 27 minutes. At the line's peak in the 1950s 19 cars were required in service, reduced to ten after 1959. 24 cars were in running order when the line closed.

As an integral part of the railway system, GCR, LNER, and later BR, the tramway featured in the public railway timetables[52] and through tickets were issued from the rest of the system. Amongst others, printed tickets between King's Cross and Immingham Dock ‘via electric cars’ were available. Local ticketing used the colourful and complex ‘Bell Punch’ system until the end.[53]

The railway was not signalled, unlike many other single-track tramways, although local signals were introduced after the Second World War at two level crossings.[54] The track on street sections in Grimsby and at Immingham used conventional grooved tramway rail; the private track sections were originally laid with flat-bottomed rail, replaced later by railway-pattern bullhead rail, and the pointwork required a different wheel profile from that normally used on tramways.[55][29]

Closure

Handling highly peaked traffic, much of it railway or dock employees travelling either free or at reduced fares, was never lucrative despite high passenger numbers (1.35 million in 1948 and over a million as late as 1956),[56] but as long as docks and railway were under common ownership and management this was a lesser consideration. Although partly re-laid in 1950[57] the in-town street section was closed from 1 July 1956 when Grimsby Corporation exercised their right to buy the line in order to abandon it, and the trams then terminated at the edge of Grimsby with a connecting bus service. Closure of the remainder was first proposed in 1958, and a bus service commenced on 28 February 1959, worked jointly over an indirect route by Grimsby Corporation and the Lincolnshire Road Car Company. A tram service was only retained in much curtailed form in peak periods, pending completion of a direct road to the industrial estate and the docks. Although the road had still not been built the tramway was again proposed for closure in 1960, and the service was finally withdrawn on 1 July 1961. Even at closure it was still handling around 250,000 passengers a year.

On the last day special trams were operated for enthusiasts, and a ceremonial last car (GCR-type tram No 4) was decorated and carried a commemorative headboard, leaving Immingham Dock at 14.12.[58][59][60]

Aftermath

Four items of rolling stock have survived.

- Original G&IER No. 14[61][62] is in the collection of the National Tramway Museum. After a lengthy period at their off-site store at Clay Cross, Derbyshire[63] it was moved to the museum's main site at Crich, Derbyshire, where it has been a static exhibit since.

- No. 20 was bought from Gateshead tramways in 1951 when it closed. When the Grimsby & Immingham closed it was sent to the National Tramway Museum, Crich, Derbyshire and restored to Gateshead livery as No. 5. It has been in and out of the operational fleet over the years, but has been on display awaiting overhaul since 2007.[64]

- No. 26 was bought from Gateshead tramways in 1951 when it closed. When the Grimsby & Immingham closed it was sent to the Beamish Museum in County Durham and restored to Gateshead livery as No. 10.[65] In 2015 it was running at the museum, temporarily in BR electric green livery.

- The Tower Maintenance Trailer[37][66] was bought by the tramway author J. H. Price when the line closed. It was sent to the National Tramway Museum, Crich, Derbyshire. In 2012 it was in use at the museum.[67]

A bench from Grimsby Corporation Bridge is part of the national collection.[14] In 2015 it was on display at the National Railway Museum, York.

In 2015 the Pyewipe Tramcar Depot, by then trackless, was in industrial use.

In 2017 eight characteristic pointed-topped, spun concrete masts used to support the overhead wires were still in situ by the site of Immingham Town, as was the brick bus (tram) shelter which was erected in the Second World War to replace the wooden version[44] and offer some air raid protection. (Sadly, the shelter was demolished by 2022. It had fallen in to a very poor state and had been filled with rubbish by fly tippers. Towards the last year or so of its life, the port company had boarded it up to help prevent further tipping)

In 2015 a number of small artifacts were kept at Immingham Museum.

See also

- Grimsby District Light Railway (Grimsby-Immingham)

- Great Grimsby and Sheffield Junction Railway (Grimsby-New Holland)

- Barton and Immingham Light Railway (Immingham-Goxhill)

References

- Price 1991, p. 59.

- Dow 1965, p. 233.

- Dow 1965, p. 234.

- Kent 1959, p. 566.

- Dow 1965, p. 242.

- Ludlam 2016, pp. 16–18.

- Wilson & Barker 1998, p. 359.

- Waller 1996, p. 35.

- Price 1991, p. 81.

- Wilson & Barker 1998, p. 360.

- Dow 1965, p. 241.

- Price 1991, p. 64.

- Skelsey 2011, p. 238.

- Price 1991, p. 82.

- Mitchell & Smith 2017, Photo 118.

- Dow 1965, p. 65.

- King & Hewins 1989, Photos 55 & 111.

- Fell & Hennessey 2012, p. 724.

- Price 1991, p. 96.

- Mitchell & Smith 2017, Photo 114.

- Bett & Gillham 1975, p. 58.

- Bates & Bairstow 2005, pp. 85 & 86.

- Waller 1996, p. 36.

- Squires 1988, p. 20.

- Price 1991, p. 97.

- Price 1991, p. 88.

- Wilson & Barker 1998, p. 366.

- Price 1991, p. 71.

- Dow 1965, p. 240.

- Mummery & Butler 1999, pp. 61, 63 & 65.

- Price 1991, p. 72.

- King & Hewins 1989, Photo 53.

- Bett & Gillham 1975, p. 59.

- King & Hewins 1989, Photo 59.

- Skelsey 2011, p. 236.

- Fell & Hennessey 2012, p. 723.

- Bates & Bairstow 2005, p. 84.

- Mummery & Butler 1999, p. 65.

- Wilson & Barker 1998, p. 362.

- ex-Newcastle cars at Immingham, via Britain from Above

- An ex-Newcastle and an ex-GCR tramcar at Corporation Bridge Bing

- A Newcastle car on Tyneside flickr

- King & Hewins 1989, Photos 47, 48, 51, 54, 57 & 58.

- Ludlam 2006, p. 427.

- Wells 1955, p. 481.

- Ludlam 2016, Inside front cover.

- Skelsey 2011, p. 237.

- Wilson & Barker 1998, p. 363.

- Mitchell & Smith 2017, Photo 116.

- Anderson 1992, p. 78.

- King & Hewins 1989, Photo 60.

- Bradshaw 1985, p. 717.

- Pask 1999, p. 13.

- Price 1991, p. 95.

- Price 1991, pp. 64, 74, 76 & 82.

- Price 1991, p. 87.

- Mitchell & Smith 2017, Photo 113.

- Price 1991, p. 101.

- Mummery & Butler 1999, p. 67.

- Wilson & Barker 1998, p. 367.

- Feather 1993, p. 3.

- Mummery & Butler 1999, p. 63.

- Bett & Gillham 1975, p. 71.

- ex-Gateshead car on display, via British Trams Online

- Price 1991, p. 106.

- Bett & Gillham 1975, p. 63.

- Fell & Hennessey 2012, p. 725.

Sources

- Anderson, Paul (1992). Railways of Lincolnshire. Oldham: Irwell Press. ISBN 978-1-871608-30-4.

- Bates, Chris; Bairstow, Martin (2005). Railways in North Lincolnshire. Leeds: Martin Bairstow. ISBN 978-1-871944-30-3.

- Bett, W. H.; Gillham, J. C. (1975). The Tramways of South Yorkshire and Humberside. Light Railway Transport League. ISBN 978-0-900433-58-0.

- Bradshaw, George (1985) [July 1922]. Bradshaw's General Railway and Steam Navigation guide for Great Britain and Ireland: A reprint of the July 1922 issue. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8708-5. OCLC 12500436.

- Dow, George (1965). Great Central, Volume Three: Fay Sets the Pace, 1900–1922. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0263-0. OCLC 500447049.

- Feather, T. (February 1993). "Great Central Inter-Urban". Forward. Great Central Railway Society. ISSN 0141-4488.

- Fell, Mike G.; Hennessey, R. A. S. (December 2012). Blakemore, Michael (ed.). "Immingham 100, The Port and Its Technology". Back Track. Easingwold: Atlantic Publishers. 26 (12). ISSN 0955-5382.

- Kent, L. (August 1959). Cooke, B.W.C. (ed.). "The Grimsby & Immingham Tramway". The Railway Magazine. London: Tothill Press Ltd. 105 (700). ISSN 0033-8923.

- King, Paul K.; Hewins, Dave R. (1989). Scenes from the Past: 5 The Railways around Grimsby, Cleethorpes, Immingham and North-east Lincolnshire. Stockport: Foxline Publishing. ISBN 978-1-870119-04-7.

- Ludlam, A.J. (2016). Immingham - A Lincolnshire Railway Centre (Lincolnshire Railway Centres). Ludborough: Lincolnshire Wolds Railway Society. ISBN 978-0-9954610-0-0.

- Ludlam, A.J. (July 2006). Kennedy, Rex (ed.). "Immingham-Gateway to the Continent". Steam Days. Bournemouth: Redgauntlet Publications (203). ISSN 0269-0020.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2017). Branch Lines North of Grimsby, including Immingham. Midhurst: Middleton Press (MD). ISBN 978-1-910356-09-8.

- Mummery, Brian; Butler, Ian (1999). Immingham and the Great Central Legacy. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7524-1714-1.

- Pask, Brian (1999). The Tickets of the Grimsby & Immingham Electric Railway. Sevenoaks: The Transport Ticket Society. ISBN 978-0-903209-33-5.

- Price, J. H. (1991). The Tramways of Grimsby, Immingham & Cleethorpes. Light Rail Transit Association. ISBN 978-0-948106-10-1.

- Skelsey, Geoffrey (April 2011). Blakemore, Michael (ed.). "Flirting with the enemy, Railway Operated Electric Tramways in the United Kingdom". Back Track. Easingwold: Atlantic Publishers. 25 (4). ISSN 0955-5382.

- Squires, Stewart E. (1988). The Lost Railways of Lincolnshire. Ware: Castlemead Publications. ISBN 978-0-948555-14-5.

- Waller, Peter (1996). The Heyday of the Tram: v. 2. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-2396-3.

- Wilson, Bryan L.; Barker, Oswald J. (October 1998). Smith, Martin (ed.). "The Grimsby & Immingham Electric Railway". Railway Bylines. Clophill: Irwell Press Limited. 3 (8). ISSN 1360-2098.

- Wells, Arthur G. (November 1955). Allen, G. Freeman (ed.). "Grimsby and Immingham Railway". Trains Illustrated. Vol. 8, no. 11. Hampton Court: Ian Allan. ISSN 0026-8356.

Further material

- Burgess, Neil (2007). Lincolnshire's Lost Railways. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84033-407-4.

- Crossland, G J; Turner, C E (2012) [2006]. Immingham A History of the Deep Water Port. T&C Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9543051-2-3.

- Goode, C. Tony (1985). Railways of North Lincolnshire. Anlaby: C.T.Goode. ISBN 978-0-9508239-7-3.

- Ludlam, A.J. (1996). Railways to New Holland and the Humber Ferries. Headington: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-494-4. LP 198.

- Smith, Martin, ed. (April 2003). "Taking the Tram". Railway Bylines. Vol. 8, no. 5. Clophill: Irwell Press. pp. 204–5. ISSN 1360-2098.

- Along LNER Lines, Part 2 (DVD), vol. 113, Uffington, Shropshire: B&R Video Productions, contains a fine short section on the tramway

- Electric Traction Archive (DVD), vol. 118, Uffington, Shropshire: B&R Video Productions, contains a fine archive section on the tramway

- The Passing of Pyewipe (DVD), Online Video, available via Great Central Railway Society, solely about the tramways of Immingham, Grimsby & Cleethorpes

- Quick, Michael (2009) [2001]. Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (4th ed.). Oxford: Railway & Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-57-5. OCLC 612226077.

- Turner, Keith (1996). The Directory of British Tramways : Every Passenger-Carrying Tramway, Past and Present. Yeovil: Haynes Publications. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-85260-549-0.

External links

- "BYGONES: Peek into tram 'volt' ..." Grimsby Telegraph. 15 May 2012.

- "The Grimsby & Immingham Tramway". www.lner.info.

- "The line on a 1940s OS map". National Library of Scotland.

- "The Grimsby street-running section on a 1951 OS map". National Library of Scotland.

- "The tramway in green". Rail Map Online.

- "Tramway photos". davesrailpics.

- "Tramway photos". YouTube. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021.

- "Tramcar No 14 at Crich". Crich Blog. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "The Tramway" (PDF). Local Transport History Soc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Tramway remains". Thorne Railway.

- "Tramcars". flickr.

- "Tramcars at Immingham Dock". geograph.

- "Tramway memorabilia at Immingham Museum". Immingham Museum. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Tramcar No. 3 at Immingham Town". sct61.

- "ex-Gateshead Tramcar". Beamish Museum.

- "ex-Gateshead Tramcar" (PDF). Tramways Monthly.

- "ex-Gateshead Tramcar in 1960s". Crich Tramway Museum. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "The Tramway". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016.

- "Pyewipe Car Sheds from the air". Britain from Above.