Pierre Schaeffer

Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer (English pronunciation: /piːˈɛər ˈhɛnriː məˈriː ˈʃeɪfər/ ⓘ, French pronunciation: [ʃɛfɛʁ]; 14 August 1910 – 19 August 1995)[1] was a French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist, acoustician and founder of Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC). His innovative work in both the sciences—particularly communications and acoustics—and the various arts of music, literature and radio presentation after the end of World War II, as well as his anti-nuclear activism and cultural criticism garnered him widespread recognition in his lifetime.

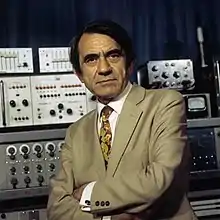

Pierre Schaeffer | |

|---|---|

Schaeffer in 1973 | |

| Born | Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer 14 August 1910 |

| Died | 19 August 1995 (aged 85) Aix-en-Provence, Bouches-du-Rhône, France |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, musician, writer, engineer, professor, broadcaster, acoustician, musicologist, record producer, inventor, entrepreneur, cultural critic |

| Years active | 1942–1990 |

| Labels | |

Amongst the vast range of works and projects he undertook, Schaeffer is most widely and currently recognized for his accomplishments in electronic and experimental music,[2] at the core of which stands his role as the chief developer of a unique and early form of avant-garde music known as musique concrète.[3] The genre emerged in Europe from the utilization of new music technology developed in the post-war era, following the advance of electroacoustic and acousmatic music.

Schaeffer's writings (which include written and radio-narrated essays, biographies, short novels, a number of musical treatises and several plays)[1][3][4] are often oriented towards his development of the genre, as well as the theoretics and philosophy of music in general.[5]

Today, Schaeffer is considered one of the most influential experimental, electroacoustic and subsequently electronic musicians, having been the first composer to utilize a number of contemporary recording and sampling techniques that are now used worldwide by nearly all record production companies.[2] His collaborative endeavors are considered milestones in the histories of electronic and experimental music.

Life

Early life and education

Schaeffer was born in Nancy in 1910.[3] His parents were both musicians (his father a violinist; his mother, a singer),[5] and at first it seemed that Pierre would also take on music as a career. However his parents discouraged his musical pursuits from childhood and had him educated in engineering.[2] He studied at several universities in this inclination, the first of which was Lycée Saint-Sigisbert located in his hometown of Nancy. Afterwards he moved westwards in 1929 to the École Polytechnique in Paris[3][6][7] and finally completed his education in the capital at the École supérieure d'électricité, in 1934.[7]

Schaeffer received a diploma in radio broadcasting from the École Polytechnique.[8] He may have also received a similar qualification from the École nationale supérieure des télécommunications, although it is not verifiable as to whether or not he ever actually attended this university.[8]

Early experimentation

Later in 1934 Schaeffer entered his first employment as an engineer, briefly working in telecommunications for the Postes et Télécommunications in Strasbourg.[7][9] In 1935 he began a relationship with a woman named Elisabeth Schmitt, and later in the year married her and with her had his first child, Marie-Claire Schaeffer.[7] He and his new family then officially relocated to Paris in 1936 where began his work in radio broadcasting and presentation.[6] It was there that he began to move away from his initial interests in telecommunications and to pursue music instead, combining his abilities as an engineer with his passion for sound. In his work at the station, Schaeffer experimented with records and an assortment of other devices—the sounds they made and the applications of those sounds—after convincing the radio station's management to allow him to use their equipment. This period of experimentation was significant for Schaeffer's development, bringing forward many fundamental questions he had on the limits of modern musical expression.[6]

In these experiments, Pierre tried playing sounds backwards, slowing them down, speeding them up and juxtaposing them with other sounds,[10] all techniques which were virtually unknown at that time.[6] He had begun working with new contemporaries whom he had met through RTF, and as such his experimentation deepened. Schaeffer's work gradually became more avant-garde, as he challenged traditional musical style with the use of various devices and practices. Eventually, a unique variety of electronic instruments—ones which Schaeffer and his colleagues created, using their own engineering skills—came into play in his work, like the chromatic, sliding and universal phonogenes, François Bayle's Acousmonium and a host of other devices such as gramaphones and some of the earliest tape recorders.[10]

Beginnings of writing career

In 1938 Schaeffer began his career as a writer, penning various articles and essays for the Revue Musicale, a French journal of music. His first column, Basic Truths, provided a critical examination of musical aspects of the time.

A known ardent Catholic, Schaeffer began to write minor religiously-based pieces, and in the same year as his Basic Truths he published his first novel: Chlothar Nicole — a short Christian novel.[11]

Club d'essai and the origin of musique concrète

The Studio d'Essai, later Club d'Essai, was founded in 1942 by Pierre Schaeffer at the Radiodiffusion Nationale (France). It played a role in the activities of the French resistance during World War II, and later became a center of musical activity.

Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète

In 1949, Schaeffer met the percussionist-composer Pierre Henry, with whom he collaborated on many different musical compositions, and in 1951, he founded the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC) in the French Radio Institution.[12] This gave him a new studio, which included a tape recorder. This was a significant development for Schaeffer, who previously had to work with phonographs and turntables to produce music.[13] Schaeffer is generally acknowledged as being the first composer to make music using magnetic tape. His continued experimentation led him to publish À la Recherche d'une Musique Concrète (French for "In Search of a Concrete Music") in 1952, which was a summation of his working methods up to that point. His only opera, Orphée 53 ("Orpheus 53"), premiered in 1953.[12]

Schaeffer left the GRMC in 1953 and reformed the group in 1958 as the Groupe de Recherche Musicale[s] (GRM) (at first without "s", then with "s").

In 1954 Schaeffer founded traditional music label Ocora ("Office de Coopération Radiophonique") alongside composer, pianist and musicologist Charles Duvelle, with a worldwide coverage in order to preserve African rural soundscapes. Ocora also served as a facility to train technicians in African national broadcasting services.

Over the years, Schaeffer mentored a number of students who went on to have successful careers in their own right including Éliane Radigue, and the young Jean Michel Jarre, who called him the first disc jockey.[14] His last "étude" (study) came in 1959: the "Study of Objects" (Études aux Objets).

Later life and death

Schaeffer became an associate professor at the Paris Conservatoire from 1968 to 1980 after creating a "class of fundamental music and application to the audiovisual."[1]

In the aftermath of the 1988 Armenian earthquake, the 78 year old Schaeffer led a 498-member French rescue team to look for survivors in Leninakan, and worked there until all foreign personnel were asked to leave.[15]

Schaeffer suffered from Alzheimer's disease later in his life, and died from the condition in Aix-en-Provence in 1995. He was 85 years old. He is buried in Delincourt in the very nice and green Vexin region (55 minutes from Paris) where he used to have his countryside property.

Schaeffer was thereafter remembered by many of his colleagues with the title, "Musician of Sounds".

Legacy

Musique concrète

Sound is the vocabulary of nature.

— Pierre Schaeffer

The term musique concrète (French for "real music", literally "concrete music"), was coined by Schaeffer in 1948.[16] Schaeffer believed traditionally classical (or as he called it, "serious") music begins as an abstraction (musical notation) that is later produced as audible music. Musique concrète, by contrast, strives to start with the "concrete" sounds that emanate from base phenomena and then abstracts them into a composition. The term musique concrète is then, in essence, the breaking down of the structured production of traditional instruments, harmony, rhythm, and even music theory itself, in an attempt to reconstruct music from the bottom up.

From the contemporary point of view, the importance of Schaeffer's musique concrète is threefold. He developed the concept of including any and all sounds into the vocabulary of music. At first he concentrated on working with sounds other than those produced by traditional musical instruments. Later on, he found it was possible to remove the familiarity of musical instrument sounds and abstract them further by techniques such as removing the attack of the recorded sound. He was among the first musicians to manipulate recorded sound for the purpose of using it in conjunction with other sounds in order to compose a musical piece. Techniques such as tape looping and tape splicing were used in his research, often comparing to sound collage. The advent of Schaeffer's manipulation of recorded sound became possible only with technologies that were developed after World War II had ended in Europe. His work is recognized today as an essential precursor to contemporary sampling practices. Schaeffer was among the first to use recording technology in a creative and specifically musical way, harnessing the power of electronic and experimental instruments in a manner similar to Luigi Russolo, whom he admired and from whose work he drew inspiration.

Furthermore, he emphasized the importance of "playing" (in his terms, jeu) in the creation of music. Schaeffer's idea of jeu comes from the French verb jouer, which carries the same double meaning as the English verb play: 'to enjoy oneself by interacting with one's surroundings', as well as 'to operate a musical instrument'. This notion is at the core of the concept of musique concrète, and reflects on freely improvised sound, or perhaps more specifically electroacoustic improvisation, from the standpoint of Schaeffer's work and research.

Influences on music

In 1955, Éliane Radigue, an apprentice of Pierre Schaeffer at Studio d'Essai, learned to cut, splice and edit tape using his techniques. She then went on to work as an assistant to Pierre Henry in 1967. However, she became more interested in tape feedback and began working on her own pieces. She composed several works (Jouet Electronique [1967], Elemental I [1968], Stress-Osaka [1969], Usral [1969], Ohmnht [1970] Vice Versa, etc [1970]) by processing the feedback between two tape recorders and a microphone.[17]

Pierre's aforementioned student in GRM, Jean Michel Jarre, went on to great international success in his own musical career. Jarre's 1997 album, Oxygene 7-13, is dedicated to Schaeffer. Pierre Henry also made a tribute to the man, composing his Écho d'Orphée, Pour P. Schaeffer alongside him for Schaeffer's last work and second compilation, L'Œuvre Musicale. His other notable pupils include Joanna Bruzdowicz, Jorge Antunes, Bernard Parmegiani, Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux, Armando Santiago, Elzbieta Sikora.Pierre Schaeffer distanced himself – voluntarily – from the musical universe in the early 1980s after criticizing the avant-garde of the 1950s, which intended to break with tradition. Contrary to this view, Schaeffer returns to music when he recognizes the virtuoso Otavio Henrique Soares Brandão as his most faithful disciple, who under his guidance performed a reading of his work "Traité dos Objets Musicaux". This reading aims to create an innovative piano and musical instrumental technique, which does not break with tradition. Pierre Schaeffer writes four fundamental texts about this recognition

Apropos of the transcription pour piano by Otavio Brandão from Pierre Schaeffer's "Étude aux Objets", In program of Soares Brandão's concert at Maison de l'Amérique Latine (Paris January 9, 1988). "Réponse à Otávio", In text of the program of the concert performed by Soares Brandão at Salle Pleyel in honor of the 80 years of Pierre Schaeffer (January 12, 1990). DECLARATION DE PIERRE SCHAEFFER SUR IBIS ET OTAVIO SOARES BRANDÃO (Paris le 13/09/1990) Declaration by Pierre Schaeffer (Porte Parole).[18][19]

Many rap albums, such as It Takes A Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back by Public Enemy and 3 Feet High And Rising by De La Soul take ordinary sounds and use them to create a finished product.[20]

Other

Today, in his honor, the Qwartz Electronic Music Awards has named several of its past events after Schaeffer. Pierre himself was a prize winner at the awards more than once.

Works

Music

All of Schaeffer's musical compositions (concrète or otherwise) were recorded before the advent of the CD, either on cassettes or a more archaic form of magnetic tape (therefore the term "discography" cannot be appropriately used here; rather his music in general). Mass-production for his work was limited at best, and each piece was, by Schaeffer's terms, intended to be released foremost as an exposé to the masses of what he believed was a new and somewhat revolutionizing form of music. The original production of his marketed work was done by the "Groupe de Recherches Musicales" (a.k.a. GRM; now owned and operated by INA or the Institut national de l'audiovisuel), the company which he initially had formed around his creations. Other music was broadcast live (Pierre himself being notable on French radio at the time) and/or done in live "concert". Some individual tracks even found their way into the use of other artists, with Pierre's work being fronted in mime performances and ballets. Now after his death, various musical production companies, such as Disques Adès and Phonurgia Nova have been given rights to distribute his work.

Below is a list of Schaeffer's musical works, showing his compositions and the year(s) they were recorded.

- Concertino-Diapason (1948; collaboration with J.-J. Grunenwald)

- Cinq études de bruits (1948)

- Suite pour 14 instruments (1949)

- Variations sur une flûte mexicaine (1949)

- Bidule en ut (1950; collaboration with Pierre Henry)

- La course au kilocycle (1950; radio score, collaboration with Pierre Henry)

- L'oiseau r.a.i. (1950)

- Symphonie pour un homme seul (1950; collaboration with Pierre Henry; revised versions in 1953, 1955, and 1966 (Henry))

- Toute la lyre (1951; pantomime, collaboration with Pierre Henry. Also known as Orphée 51)

- Masquerage (1952; film score)

- Les paroles dégelées (1952; music for a radio production)

- Scènes de Don Juan (1952; incidental music, collaboration with Monique Rollin)

- Orphée 53 (1953; opera)

- Sahara d'aujourd'hui (1957; film score, collaboration with Pierre Henry)

- Continuo (1958; collaboration with Luc Ferrari)

- Etude aux sons animés (1958)

- Etude aux allures (1958)

- Exposition française à Londres (1958; collaboration with Luc Ferrari)

- Etude aux objets (1959)

- Nocturne aux chemins de fer (1959; incidental music)

- Phèdre (1959; incidental music)

- Simultané camerounais (1959)

- Phèdre (1961)

- L'aura d'Olga (1962; music for a radio production, collaboration with Claude Arrieu)

- Le trièdre fertile (1975; collaboration with Bernard Durr)

- Bilude (1979)

Broadcast narratives

Apart from his published and publicized music, Schaeffer conducted several musical (and specifically musique concrète-related) presentations via French radio. Although these broadcasts contained musical pieces by Schaeffer they cannot be adequately described as part of his main line of musical output. This is because the radio "essays", as they were appropriately named, were mainly narration on Schaeffer's musical theories philosophies rather than compositions in and of themselves.

Schaeffer's radio narratives include the following:

- The Shell Filled With Planets (1944)

- Cantata to Alsace (1945)

- An Hour of the World (1946)

- From Claudel to Brangues (1953)

- Ten Years of Radiophonic Experiments from the 'Studio' to the 'Club' d'Essai: 1942–1952 (1955)

Selected writings

Schaeffer's literary works span a range of genres, both in terms of fiction and non-fiction. He predominantly wrote treatises and essays, but also penned a film review and two plays. An ardent Catholic, Schaeffer wrote Chlothar Nicole (French: Clotaire Nicole; published 1938)—a Christian novel or short story—and Tobias (French: Tobie; published 1939) a religiously-based play.

Novels and short stories

- Chlothar Nicole (1938)

- The Guardian of The Volcano (1969)

- Prelude, Chorale and Fugue (1981)

Plays

- Tobie (1939)

- Secular Games (1946)

Non-fiction

- America, We Ignore You (1946)

- The Non-Visual Element of Films (1946)

- In Search of a Concrete Music (1952)

- Traité des objets musicaux (1966)

- Solfège de l'objet sonore (1967)

- Music and Acoustics (1967)

References

- Notes

- "Pierre Schaeffer". Encyclopædia Britannica: ¶2. Retrieved 4 December 2008. "Schaeffer taught electronic composition at the Paris Conservatory from 1968 until 1980. His writings include novels, short stories, and essays, as well as theoretical works in music, such as À la recherche d'une musique concrète (1952; 'In Search of a Concrete Music"'), Traité des objets musicaux (1966; 'Treatise on Musical Objects'), and the two-volume Machines à communiquer (1970–72; 'Machines for Communicating')."

- "Pierre Schaeffer & Pierre Henry: Pioneers in Sampling". Unknown author (reproduction via Diliberto, John 2005: Electronic Musician) 1986: Electronic Musician. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "Pierre Schaeffer". Snyder, Jeff 2007: CsUNIX1/Lebanon Valley College: 1, 3. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- "Les écrits de Pierre Schaeffer". Couprie, Pierre & OLATS 2000 (in French). Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "Musique Concrète Revisited". Palombini, Carlos 1999: The Electronic Musicological Review. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- "Pierre Schaeffer: Profile on Discogs.com". Anonymous/Various, submitted 2003: Discogs.com. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- "Pierre Schaeffer Biographie". Couprie, Pierre & OLATS 2000 (in French). Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- "Excerpt from Electronic Music, 1948–1953" (PDF). Cross, Lowell [unverifiable date]: Forum: Electronic Music and Computer Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- Sitsky, Larry (2002). Excerpt from Music of the Twentieth-century Avant-garde. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313296895. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "A-Z of Instruments – Other". The Foundry Creative Media Company Ltd. 2005: sec. 2. Archived from the original on 22 April 2003. Retrieved 7 December 2009. "Musique concrète was an experimental technique that combined pre-recorded sounds natural as well as musical to make musical compositions. Using only the earliest tape recorders, sounds were edited, played backwards and speeded up and down to create fascinating 'sound-scapes'. Pierre Henry was a prolific composer of musique concrète and collaborated with Schaeffer on many compositions. Luciano Berio and Steve Reich are also key figures in musique concrète composition. Karlheinz Stockhausen combined electronic and concrète sounds to become a leader of avant-garde music making."

- de Reydellet, Jean (1996). "Pierre Schaeffer, 1910–1995: The Founder of "Musique Concrète"". Computer Music Journal. 20 (2): 10–11. ISSN 0148-9267. JSTOR 3681324.

- "The 'Groupe de Recherches Musicales' Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry & Jacques Poullin, France 1951". 26 December 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Teruggi, Daniel (2007). "Technology and musique concrète: the technical developments of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales and their implication in musical composition". Organised Sound. 12 (3): 213–231. doi:10.1017/S1355771807001914. ISSN 1469-8153. S2CID 37881462.

- "Electronic Vibrations: Ein Sound erobert die Welt" [Electronic Vibrations: A sound conquers the world]. WDR Klassik (in German). Westdeutscher Rundfunk. 19 October 2022. 8:00-8:50. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- Keller, Bill (16 December 1988). "As Hope Dies, Quake Rescuers Pull Out". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

-

- Kennedy, Michael (2006), The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 985 pages, ISBN 0-19-861459-4

- Rodgers, Tara (2010). Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822394150. ISBN 978-0-8223-4661-6.

- TEXTES DE PIERRE SCHAEFFER À PROPOS D´OTAVIO HENRIQUE SOARES BRANDÃO by ibis soares brandao – Issuu

- Otavio Henrique Soares Brandao – Piano – Resposta a Schaeffer I, by Otavio Soares Brandão.

- The Effects of Musique Concrete at Musique Concrete – History and Figures "FAU Electronic Music - Musique Concrete: History and Figures". Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Sources

- Dalibor Davidović, Nikša Gligo, Seadeta Midžić, Daniel Teruggi, and Jerica Ziherl (eds.) (2011). Proceedings of the International Conference Pierre Schaeffer: mediArt, with a foreword by Ivo Malec, papers by Daniel Teruggi, François Bayle, Jocelyne Tournet-Lammer, Dieter Kaufmann, Francisco Rivas, Seadeta Midžić, Marc Battier, Brian Willems, Leigh Landy, Cedric Maridet, Hans Peter Kuhn, Tatjana Böhme-Mehner, Jelena Novak, Martin Laliberté, Suk-Jun Kim, Darko Fritz, Stephen McCourt, Biljana Srećković, and Elzbieta Sikora. Rijeka: Muzej moderne i suvremene umjetnosti. ISBN 978-953-6501-78-6.

- Martial Robert (1999). Communication et musique en France entre 1936 et 1986 (in French). Paris, France: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-7975-8.

- Pierre Schaeffer (1966). Traité des objets musicaux (Treatise on Musical Objects) (in French). Paris, France: Le Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-002608-6.

- Pierre Schaeffer (1987). Interview with Pierre Schaeffer. London, U.K.: Rer Quarterly Vol 2,1, 1987.

External links

- Le Groupe de Recherches Musicales at the Institut national de l'audiovisuel (in French)

- Club d'Essai – Unofficial website of Club d'Essai (in Portuguese)

- Pierre Schaeffer at the online alumni community of the École Polytechnique (in French)

- Pierre Schaeffer at the Electronic Music Foundation

- Pierre Schaeffer at AllMusic

- Pierre Schaeffer at BBC Music

- Pierre Schaeffer at Discogs