Les XX

Les XX (French; "Les Vingt"; French pronunciation: [le vɛ̃]; lit. 'The 20') was a group of twenty Belgian painters, designers and sculptors, formed in 1883 by the Brussels lawyer, publisher, and entrepreneur Octave Maus. For ten years, they held an annual exhibition of their art; each year 20 other international artists were also invited to participate in their exhibition. Painters invited include Camille Pissarro (1887, 1889, 1891), Claude Monet (1886, 1889), Georges Seurat (1887, 1889, 1891, 1892), Paul Gauguin (1889, 1891), Paul Cézanne (1890), and Vincent van Gogh (1890, 1891 retrospective).

Les XX was in some ways a successor to another group, L'Essor. The rejection of James Ensor's The Oyster Eater in 1883 by L'Essor Salon, following the earlier rejection by the Antwerp Salon, was one of the events that led to the formation of Les XX. The ideal of the group responded to the theories of Viollet le Duc, in particular that of the integration of the so-called minor arts (decorative arts) with the major arts (architecture).

In 1893, the society of Les XX was transformed into "La Libre Esthétique".

History

Les XX was founded on 28 October 1883 in Brussels and held annual shows there between 1884 and 1893, usually in January–March. The group was founded by 11 artists who were unhappy with the conservative policies of both the official academic Salon and the internal bureaucracy of L'Essor, under a governing committee of twenty members. Unlike L'Essor ('Soaring'), which had also been set up in opposition to the Salon, Les XX had no president or governing committee. Instead Octave Maus (a lawyer who was also an art critic and journalist) acted as the secretary of Les XX, while other duties, including the organization of the annual exhibitions, were dispatched by a rotating committee of three members. A further nine artists were invited to join to bring the group membership of Les XX to twenty. In addition to the exhibits of its Belgian members, foreign artists were also invited to exhibit.[1]

There was a close tie between art, music and literature among the Les XX artists. During the exhibitions, there were literary lectures and discussions, and performances of new classical music, which from 1888 were organised by Vincent d'Indy,[2] with from 1889 until the end in 1893 very frequent performances by the Quatuor Ysaÿe.[3] Concerts included recently composed music by Claude Debussy, Ernest Chausson and Gabriel Fauré. Leading exponents of the Symbolist movement who gave lectures include Stéphane Mallarmé, Théodore de Wyzewa and Paul Verlaine.[1]

Together with Maus, the influential jurist Edmond Picard and the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren provided the driving force behind an associated periodical, L'Art Moderne, which was started in 1881. This publication aggressively defended Les XX from attacks by critics and members of the visiting public. Picard polemically fomented tensions both with the artistic establishment and within Les XX. By 1887, six of the more conservative original members had left, sometimes under pressure from Picard and Maus, to be replaced by artists who were more sympathetic to the cause. Altogether, Les XX had 32 members during the ten years of its existence.[1]

Eleven founding members

- James Ensor 1860–1949 (member until 1893)[4]

- Théo van Rysselberghe 1862–1926 (member until 1893)[5]

- Fernand Khnopff 1858–1921 (member until 1893)[4]

- Alfred William Finch[5]

- Frantz Charlet 1862–1928[5]

- Paul Du Bois[5]

- Charles Goethals c. 1853–85[5]

- Darío de Regoyos (Spanish)[5]

- Willy Schlobach 1864–1951[5]

- Guillaume Van Strydonck 1861–1937[5]

- Rodolphe Wytsman 1860–1927[5]

Nine invited members

- Guillaume Vogels

- Achille Chainaye 1862–1915

- Jean Delvin 1853–1922[6]

- Jef Lambeaux[6]

- Périclès Pantazis (Greek) 1849–1884[6]

- Frans Simons 1855–1919

- Gustave Vanaise 1854–1902

- Piet Verhaert 1852–1908

- Theodoor Verstraete 1851–1907

Twelve later invited members

- Félicien Rops 1833–1898

- Georges Lemmen 1865–1916 (member starting 1888)[7]

- George Minne 1866–1941

- Anna Boch 1848–1926 (member 1885–1893: only female member)[8]

- Henry van de Velde (member starting 1888)[9]

- Guillaume Charlier

- Henry De Groux

- Robert Picard (artist) b. 1870

- Jan Toorop (Dutch)[10]

- Odilon Redon (French)

- Paul Signac (French)[4]

- Isidore Verheyden (member 1884–1888)[8]

The ten Annual Exhibitions of Les XX, 1884–1893

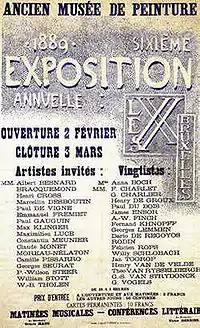

The 1884, 1885 and 1886 exhibitions were held at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. The later exhibitions were all held at the Museum of Modern Art of Brussels.[11]

1884

The first of ten annual exhibitions was held on 2 February at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels.[6]

Apart from the members of Les XX, there were exhibitions by Adriaan Jozef Heymans, Jan Stobbaerts, Auguste Rodin, James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Max Liebermann.[12][13]

Catulle Mendès discussed Richard Wagner.[14]

1885

Exhibition of Xavier Mellery[6] and Jan Toorop.[10]

1886

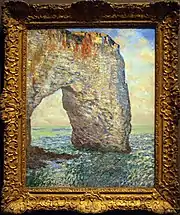

Exhibits of Pierre-Auguste Renoir,[4] Odilon Redon[15] and Claude Monet, including Le pont d'Argenteuil and La Manneporte à Étretat.[14]

First performance of César Franck's Violon Sonata.[16]

1887

Walter Sickert,[17] Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot and Georges-Pierre Seurat exhibit, with Seurat and Signac present at the opening.[4] The major work shown is Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.[5]

In July, Les XX had an exhibition in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.[11]

1888

Exhibits of Albert Dubois-Pillet,[18] Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri-Edmond Cross, James Abbott McNeill Whistler,[2] Paul Signac and Odilon Redon.[4]

First performance of Vincent d'Indy's Poème des Montagnes.[16]

Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam was one of the invited writers.[14]

1889

Camille Pissarro,[5] Maximilien Luce,[5] Henri-Edmond Cross, Gustave Caillebotte,[2] Paul Cézanne,[18] Albert Dubois-Pillet,[18] Paul Gauguin and Georges Seurat exhibit.[4] Included is Gauguin's masterpiece Vision After the Sermon.[10]

At the first concert, the music was composed by César Franck, Pierre de Bréville, Ernest Chausson, Gabriel Fauré and Julien Tiersot. The music was played in part by the Quatuor Ysaÿe, as happened in the next few years.[3] The second concert was centered on Gabriel Fauré, with additional music by d'Indy, Charles Bordes and Henri Duparc.[3]

In July, Les XX had an exhibition in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.[11]

1890

Exhibits by invited artists including Odilon Redon,[15] Paul Cézanne,[2] Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec,[7] Alfred Sisley, Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.[14] During the 1890 expo Vincent van Gogh exhibited six paintings and sold The Red Vineyard, the only painting he sold during his lifetime.[19]

Three concerts were given, with the first centered on Belgian composers like Auguste Dupont, Léon Soubre, Joseph Jacob, Paul Gilson and Gustave Huberti.[3] The second and third concert focused on the French composers, with works by Fauré, Franck, d'Indy, and Castillon in the second concert. Vincent d'Indy performed his Symphonie Cévenole in the third concert.[20] Other composers whose work was performed were Fauré, Franck, Bréville, Bordes, Chausson, Albéric Magnard and Paul Vidal.[3]

Stéphane Mallarmé gave a lecture on Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam; Edmond Picard discusses Maurice Maeterlinck, Emile Verhaeren and Charles Van Lerberghe.[14]

1891

Exhibitions of Georges Seurat,[4] Camille Pissarro,[5] Alfred Sisley,[14] and Jules Chéret.[18]

First exhibitions of decorative art, including posters and book illustrations by Walter Crane, Alfred William Finch's first attempts at ceramics,[21] and three vases and a statue by Paul Gauguin. Retrospective for Vincent van Gogh. Catalogue cover designed by Georges Lemmen.[22]

Memorial concert for César Franck and a second concert with new work by Vincent d'Indy,[2] and work by other followers of Franck, including Bordes, Duparc, Bréville, Chausson, Tiersot, Vidal, and Camille Benoît. Also played was work by Fauré and Emmanuel Chabrier.[3] A third concert focused on Russian composers, with works by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Shcherbachov, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Kopylov.[3]

1892

Pottery exhibited by Auguste Delaherche, and embroidery designs by Henry Van de Velde.[23] Invited artists include Maximilien Luce,[5] Léo Gausson[18] and Mary Cassatt.[14]

Retrospective of Georges Seurat with 18 paintings, including La Cirque and La Parade.[23]

Three concert evenings were organised. The first concert presented the first version of Paul Gilson's La Mer, Guillaume Lekeu's Andromède and music by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Glazunov, and Franz Servais.[24] The second showcased music by Alexis de Castillon, César Franck, Charles Bordes, Louis de Serres and Emmanuel Chabrier.[3] The final concert included the first performance of Vincent d'Indy's Suite in D and Ernest Chausson's Concert.[16] The other music played was composed by Gabriel Fauré, Charles Bordes, Camille Chevillard and Albéric Magnard.[3]

1893

More design was exhibited, including a table by Alfred William Finch, embroidery by Henry Van de Velde, and objects by Alexandre Charpentier.[23]

Paul Verlaine discussed the contemporary poetry.[14]

The first concert was centered on work by César Franck and the first performance of Ernest Chausson's Poème de l'amour et la mer The second concert contained works by d'Indy, Castillon, Fauré, Chabrier and Bréville.[3] The third and final concert featured the première of Guillaume Lekeu's Violin Sonata,[16] with also performances of compositions by Charles Smulders, Paul Gilson, Dorsan van Reysschoot and Alexis de Castillon.[24]

Notes

- Block, Jane. "XX, Les". Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 March 2014. (subscription required)

- Schwartz, Manuela (2006). Vincent d'Indy et son temps. Mardaga. p. 391. ISBN 978-2-87009-888-2. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Stockhem, Michel (1990). Eugène Ysaÿe et la musique de chambre (in French). Mardaga. p. 270. ISBN 978-2-87009-399-3. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Walther, Ingo F.; Suckle, Robert; Wundram, Manfred (2002). Masterpieces of Western Art. Vol. 1. Taschen. p. 760. ISBN 978-3-8228-1825-1. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Clement, Russell T.; Houzé, Annick (1999). Neo-impressionist painters. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-313-30382-1. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- State, Paul F. (2004). Historical dictionary of Brussels. Scarecrow Press. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-8108-5075-0. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Ploegaerts, Léon; Puttemans, Pierre (1987). L'œuvre architecturale de Henry van de Velde (in French). Presses Université Laval. p. 462. ISBN 978-2-7637-7112-0. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Gaze, Delia (1997). Dictionary of women artists, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 1512. ISBN 978-1-884964-21-3. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- James, Kathleen (2006). Bauhaus culture: from Weimar to the Cold War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8166-4688-3. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Frijhoff, Willem; Spies (2004). Dutch Culture in a European Perspective. Vol. 3. Marijke. Van Gorcum. p. 598. ISBN 978-90-232-3965-9. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Feltkamp, Ronald (2003). Théo van Rysselberghe, 1862-1926: monographie et catalogue raisonné. Lannoo. p. 535. ISBN 978-2-85917-389-0. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Giedion, Sigfried (2007). Raum, Zeit, Architektur: Die Entstehung einer neuen Tradition (in German). Springer. p. 536. ISBN 978-3-7643-5407-7. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Jules Dujardin, 'L Art Flamand: Les Artistes Contemporains', Published by Nabu Press, United States 2012, ISBN 1248865537, p. 58

- Legrand, Francine-Claire (1999). James Ensor (in French). Renaissance Du Livre. p. 144. ISBN 978-2-8046-0295-6. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Clement, Russell T. (1996). Four French symbolists. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-313-29752-6. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Langham Smith, Richard; Potter, Caroline (2006). French music since Berlioz. Ashgate Publishing. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-7546-0282-8. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Baron, Wendy (2006). Sickert: paintings and drawings. Yale University Press. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-300-11129-3. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Turner, Jane (2000). The Grove dictionary of art. Oxford University Press US. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-312-22971-9. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- "History of the Red Vineyard".

- Thomson, Andrew (1996). Vincent D'Indy and his world. Oxford University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-19-816220-9. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Howard, Jeremy (1996). Art nouveau: international and national styles in Europe. Manchester University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-7190-4161-7. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Weisberg, Gabriël P.; Dixon, Laurinda S.; Lemke, Antje Bultmann (1987). The Documented image: visions in art history. Syracuse University Press. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-8156-2410-3.

- Tschudi-Madsen, Stephan (2002). The art nouveau style. Courier Dover. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-486-41794-3. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Lekeu, Guillaume (1993). Verdebout, Luc (ed.). Correspondance. Mardaga. p. 496. ISBN 978-2-87009-557-7. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Octave Maus: L'Espagne des artistes (Brussels, 1887).

- Octave Maus: Souvenirs d'un Wagnériste: Le Théâtre de Bayreuth (Brussels, 1888).

- Octave Maus: Les Préludes: Impressions d'adolescence (Brussels, 1921).

- Madeleine Octave Maus: Trente années de l'lutte pour l'art, Librairie L'Oiseau bleau, Bruxelles 1926; reprinted by Éditions Lebeer Hossmann, Bruxelles 1980

Secondary sources

- Autour de 1900: L'Art Belge (1884–1918). London: The Arts Council, 1965.

- Block, Jane, Les XX and Belgian Avant-Gardism 1868–1894, Studies in Fine Arts: The Avant garde, Ann Arbor: UMI Research press, 1984.

- Herbert, Robert. Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991. ISBN 9780870996184.

- Les XX, Bruxelles. Catalogue des dix expositions annuelles, Brussels: Centre international pour l'étude de XIXe siècle, 1981.

- Stevens, Mary Anne and Hoozee, Robert (eds.), Impressionism to Symbolism: The Belgian Avant-Garde 1880–1900, exhib. cat. London: Royal Academy of Arts, London 7 July – 2 October 1994.