Guaynabo, Puerto Rico

Guaynabo (Spanish pronunciation: [ɡwajˈnaβo], locally [wajˈnaβo]) is a city, suburb of San Juan and municipality in the northern part of Puerto Rico, located in the northern coast of the island, north of Aguas Buenas, south of Cataño, east of Bayamón, and west of San Juan. Guaynabo is spread over 9 barrios and Guaynabo Pueblo (the downtown area and the administrative center of the suburb). Guaynabo is considered, along with its neighbors – San Juan and the municipalities of Bayamón, Carolina, Cataño, Trujillo Alto, and Toa Baja – to be part of the San Juan metropolitan area. It is also part of the larger San Juan-Caguas-Guaynabo Metropolitan Statistical Area, (the largest MSA in Puerto Rico).

Guaynabo

Municipio Autónomo de Guaynabo | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

Guaynabo's Central Business District in 2013. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: "Ciudad de los Conquistadores", "Pueblo del Carnaval Mabó", "Primer Poblado de Puerto Rico" | |

| Anthem: "Guaynabo, Pueblo Querido" | |

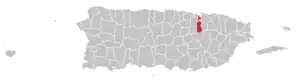

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Guaynabo Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°22′00″N 66°06′00″W | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Founded | 1769 |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Edward O'Neill Rosa (PNP) |

| • Senatorial District | 1 - San Juan (Half) 2 - Bayamon (Half) |

| • Representative dist. | 6 / 9 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27.1 sq mi (70.2 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 89,780 |

| • Rank | 6th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 3,300/sq mi (1,300/km2) |

| Demonym | Guaynabeño(s) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Codes | 00965, 00966, 00968, 00969, 00971, 00970 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

| Website | guaynabocity.gov.pr |

The municipality has a land area of 27.13 square miles (70.3 km2) and a population of 89,780 as of the 2020 census. The municipality is known for being an affluent suburb of San Juan and for its former Irish heritage. The studios of WAPA-TV is located in Guaynabo.

History

The first European settlement in Puerto Rico, Caparra, was founded in 1508 by Juan Ponce de León in land that is today part of Guaynabo. Ponce de León resided there as first Spanish governor of Puerto Rico. This settlement was abandoned in 1521 in favor of San Juan. The ruins of Caparra remain and are a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The Museum of the Conquest and Colonization of Puerto Rico, which features artifacts from the site and others in Puerto Rico, is located on the grounds.

The municipality of Guaynabo was founded in 1769 by Pedro R. Davila (P.R.), after a struggle for division from the municipality of Bayamón. Previously, the municipality was known as Buinabo, a name that it is popularly said to mean in Taíno "Here is another place of fresh water." Irish officer Thomas O'Daly and fellow Irishman Miguel Kirwan settled the area in the late 18th century and developed a farm and sugarcane plantation he named Hacienda San Patricio. The plantation no longer exists but the land on which it was located is now the central business district of Guaynabo and the San Patricio Plaza shopping mall.

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico. In Guaynabo, where 26.9% of the population live below the poverty level, 2800 homes were destroyed.[2] The hurricane triggered numerous landslides in Guaynabo.[3][4] Then president Donald Trump and his wife, Melania Trump visited Guaynabo.[5] Due to the municipality's fiscal difficulties, it was not until April 2, 2019, over a year and half later, that the overtime pay owed to municipal workers was paid.[6]

After 24 years as mayor, Héctor O'Neill García resigned in 2017 when allegations surfaced of sexual harassment toward a female municipal employee.[7] He was replaced in a run-off election by Angel Pérez Otero, who in turn was forced out due to his arrest for Federal corruption allegations in 2021.[8] Héctor O'Neill's son Edward O'Neill Rosa won the following run-off election to succeed him as mayor in January 2022.[9]

Geography

Guaynabo is on the northern side.[10]

Barrios

Like all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Guaynabo is subdivided into barrios. The municipal buildings, central square and large Catholic church are located in a smaller barrio referred to as "el pueblo", located near the center of the municipality.[11][12][13][14]

Sectors

Barrios (which are, in contemporary times, roughly comparable to minor civil divisions)[15] in turn are further subdivided into smaller local populated place areas/units called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[16][17][18]

Special Communities

Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Guaynabo: Amelia, Buen Samaritano, Camarones barrio, Corea, El Polvorín, Honduras, Jerusalén, Los Filtros, Sector El Laberinto, Sector La Pajilla, Sector Los Ratones (Camino Feliciano), Sector San Miguel, Trujillo, Sector Tomé, Vietnam,[19] and Villa Isleña.[20][21]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 10,800 | — | |

| 1930 | 13,502 | 25.0% | |

| 1940 | 18,319 | 35.7% | |

| 1950 | 29,120 | 59.0% | |

| 1960 | 39,718 | 36.4% | |

| 1970 | 67,042 | 68.8% | |

| 1980 | 80,742 | 20.4% | |

| 1990 | 92,886 | 15.0% | |

| 2000 | 100,053 | 7.7% | |

| 2010 | 97,924 | −2.1% | |

| 2020 | 89,780 | −8.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] 1920-1930[23] 1930-1950[24] 1960-2000[25] 2010[13] 2020[26] | |||

Tourism

Landmarks and places of interest

- Rancho de Apa (restaurant)[27]

- Centro de Bellas Artes (Guaynabo Performing Arts Center)

- Caparra Ruins

- Caribe Recreational Center

- Iglesia Parroquial de San Pedro Mártir

- La Marquesa Forest Park

- Paseo Tablado

- Mario Morales Coliseum

- San Patricio Plaza

- Caparra Country Club

- Plaza Guaynabo

- Museum of Transportation

- Museo del Deporte

- Fort Buchanan

Economy

Several businesses have their headquarters or local Puerto Rican branches in Guaynabo. El Nuevo Día,[28] Chrysler, Santander Securities, Puerto Rico Telephone, and many sales offices for large US and international firms (such as Total, Microsoft, Toshiba, Puma Energy and others) have their Puerto Rican headquarters in Guaynabo. WAPA-TV (Televicentro) and Univision Puerto Rico have their main studios in Guaynabo.

Crime

Carjackings have been an ongoing problem in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico[30][31][32][33][34] and in 2014 the FBI reported a carjacking that occurred in Camarones.[35]

Climate

| Climate data for Guaynabo, Puerto Rico | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 94 (34) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

92 (33) |

98 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

85 (29) |

86 (30) |

87 (31) |

88 (31) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

67 (19) |

67 (19) |

69 (21) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

73 (23) |

74 (23) |

73 (23) |

73 (23) |

71 (22) |

68 (20) |

67 (19) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 50 (10) |

45 (7) |

45 (7) |

60 (16) |

59 (15) |

55 (13) |

55 (13) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

55 (13) |

50 (10) |

45 (7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.79 (122) |

3.30 (84) |

3.52 (89) |

5.80 (147) |

7.17 (182) |

4.54 (115) |

6.70 (170) |

6.44 (164) |

7.39 (188) |

6.79 (172) |

8.06 (205) |

6.39 (162) |

70.89 (1,800) |

| Source: weather.com[36] | |||||||||||||

Culture

Festivals and events

Guaynabo celebrates its patron saint festival in April. The Fiestas Patronales de San Pedro Martir is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[10][37]

Other festivals and events celebrated in Guaynabo include:

- Three Kings Festival – January

- Mabó Carnival – February

- Mothers’ Day celebration – May

- National Salsa Day – June

- Fine Arts camp and recreation and sports camp – June

- Bomba and Plena (folkloric music and dance) Festival – October

- Official lighting of Christmas Lights – November

Sports

Guaynabo's old BSN team, the Guaynabo Mets, won national championships in 1980, 1982 and 1989, commanded by the player whom the Mario Morales Coliseum was named after, Mario "Quijote" Morales. The Conquistadores de Guaynabo, or Guaynabo Conquistadores, are the Guaynabo Mets replacement and still play in the Mario Morales Coliseum. The Mets de Guaynabo are the local women's volleyball team that play in the Liga de Voleibol Superior Femenino (LVSF). They have not won any championships yet. They also play in the Mario Morales Coliseum. Guaynabo Fluminense FC is Guaynabo's professional soccer team that plays in the Puerto Rico Soccer League. The league started in 2008 and Guaynabo's current position in the league is 4th place. Guaynabo Fluminense FC play their matches at the Jose Bonano Stadium that was originally made for baseball, but became a soccer arena after the Puerto Rico Baseball League was cancelled for the 2008 season. It was at the same year that the Puerto Rico Soccer League was starting to take place. In the 2009 season, Guaynabo Fluminense FC moved to the Sixto Escobar Stadium.

- Mets de Guaynabo (women's volleyball) - Liga de Voleibol Superior Femenino (LVSF)

- Mets de Guaynabo (men's volleyball) - Liga de Voleibol Superior Masculino (LVSM)

- Guaynabo Conquistadores (basketball) - Baloncesto Superior Nacional (BSN)

- Mets de Guaynabo (basketball) - Baloncesto Superior Nacional (BSN)

- Mets de Guaynabo (baseball) - Federación de Béisbol Aficionado de Puerto Rico (Béisbol Doble A)

- Guaynabo Fluminense FC (soccer) - Puerto Rico Soccer League (PRSL)

Government and infrastructure

The United States Postal Service operates two post offices, Guaynabo and Caparra Heights, in Guaynabo.[38][39]

The Federal Bureau of Prisons operates the Metropolitan Detention Center, Guaynabo in Guaynabo.[40]

Some regions of the city belong to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district I while others belong to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district II. Both of the Districts are represented by two Senators. In 2016, Henry Neumann and Miguel Romero were elected as Senators for District I, while Migdalia Padilla and Carmelo Ríos have been serving as Senators for District II since being elected in 2004.[41]

Mayors of Guaynabo from 1969 to present

| Mayor | Term | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Ebenezer Rivera | 1969–1979 | New Progressive Party |

| Alejandro Cruz Ortiz | 1979–1993 | New Progressive Party |

| Héctor O'Neill García | 1993–2017 | New Progressive Party |

| Angel Pérez Otero | 2017–2021 | New Progressive Party |

| Edward O'Neill Rosa | 2022–Present | New Progressive Party |

Mayors of Guaynabo from 1782 to 1969

Term Name 1782 Cayetano de la Sarna 1800 Pedro Dávila 1812 Dionisio Cátala 1816 Angel Umpierre 1818 Juan José González 1821 Joaquín Goyena 1822 José María Prosis 1823 Simón Hinonio 1825 José R. Ramírez 1827 Antonio Guzmán 1828 Genaro Oller 1836 Andrés Degal 1836 Agustín Rosario 1840 Francisco Hiques 1844 Martínez Díaz 1848 Tomás Cátla 1849 Andrés Vega 1852 Justo García 1856 José Tomás Sagarra 1857 Manuel Manzano 1859 Juan Floret 1859 José Francisco Chiques 1862 Segundo de Echeverte 1862 José de Murgas 1869 Juan J. Caro 1873 Benito Gómez 1874 Manuel Millones 1876 José Otero 1891 Juan Díaz de Barrio 1914 José Ramón 1914 José Carazo 1919 Narciso Vall-llobera Feliú 1924 Zenón Díaz Valcárcel 1936 Dolores Valdivieso 1944 Augosto Rivera 1948 Jorge Gavillán Fuentes 1956 Juan Román 1964 José Rosario Reyes

Symbols

The municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[42]

Flag

This municipality has a flag.[43]

Coat of arms

This municipality has a coat of arms.[43]

Health facilities

Professional Hospital Guaynabo located on Felisa Rincón Avenue (formerly Las Cumbres Avenue), is the newest hospital infrastructure built in Puerto Rico. Guaynabo is the only city in Puerto Rico to have a hospital specialized in advanced vascular surgery.[44] Some of the first and newest procedures performed in Puerto Rico during 2009 were done in Professional Hospital Guaynabo, including the first AxiaLIF surgery for lumbar fusion.[45]

Transportation

The Tren Urbano has only one station in the municipality, Torrimar Station. Guaynabo has a bus network called “Guaynabo City Transport”. There are 63 bridges in Guaynabo.[46]

Notable people

- Tomas Nido, Baseball Catcher for the New York Mets

- Iván DeJesús Jr., Baseball player infielder

Education

Guaynabo is home to Atlantic University College, which specializes in new media art.

The Japanese Language School of Puerto Rico (プエルトリコ補習授業校 Puerutoriko Hoshū Jugyō Kō), a weekend Japanese school, previously held its classes in Guaynabo.[47] It closed in March 2006.[48]

International relations

Guaynabo serves as a host city to four foreign consulates with business in Puerto Rico:

Gallery

Skyline of Guaynabo

Skyline of Guaynabo PR-1 and PR-8834 in Guaynabo

PR-1 and PR-8834 in Guaynabo Metropolitan Detention Center in Guaynabo

Metropolitan Detention Center in Guaynabo

References

- Bureau, US Census. "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "María, un nombre que no vamos a olvidar. María derrumbó las barreras sociales de Guaynabo y mostró a Trump frente a la tragedia" [Maria, a name we will never forget. María broke down the social barriers of Guaynabo and showcased Trump in the face of tragedy]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). June 13, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico" (PDF). USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "Trump Touts Relief Efforts In Puerto Rico: 'We've Saved A Lot Of Lives'". NPR.org. October 3, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- "Guaynabo culmina pago a empleados de horas extra trabajadas durante María". April 2, 2019. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Puerto Rico governor reacts to mayor's resignation". Caribbean Business. June 6, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- "Puerto Rico mayor, official charged in US corruption case". ABC News. Associated Press. December 9, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- Rolón Cintrón, Heidi (February 15, 2022). "Edward O'Neill se proclama nuevo alcalde de Guaynabo". El Nuevo Día. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- "Guaynabo Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Picó, Rafael; Buitrago de Santiago, Zayda; Berrios, Hector H. (1969). Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social, por Rafael Picó. Con la colaboración de Zayda Buitrago de Santiago y Héctor H. Berrios. San Juan Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Puerto Rico,1969. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- Gwillim Law (May 20, 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- "Map of Guaynabo" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 30, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- "Vietnam: Una comunidad marcada por la expropiación forzosa – AL DÍA | PUERTO RICO". May 15, 2014. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- "Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). August 8, 2011. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza:Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (Primera edición ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930 1920 and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Bureau, US Census. "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- Modak, Sebastian (February 15, 2019). "Visiting Puerto Rico, and Finding the up Beat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- "Contáctanos - El Nuevo Día". www.elnuevodia.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Iberia Around the World." Iberia. Accessed September 11, 2008. "In the rest of the world - Puerto Rico" - "San Juan de Puerto Rico. City office - Metro Office Park Calle 1 Lote 3 Oficina 102 Guaynabo, Puerto Rico 00968."

- "Carjacking en Guaynabo". La Perla del Sur. March 3, 2019. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Rico, Metro Puerto. "Sacan familia de auto para hacer carjacking en Guaynabo". Metro. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- PR, Por TELEMUNDO. "Video: Carjacking en centro comercial de Guaynabo - Telemundo Puerto Rico". Telemundo PR. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- VOCERO, Nicole Candelaria, Especial para EL. "Investigan carjacking en Guaynabo". El Vocero de Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Mujer víctima de carjacking a punta de pistola en Guaynabo". Primera Hora. January 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- "Arrests of Elvin Manuel Otero Tarzia, Sebastian Angelo Saldana, Kevin Rivera Ruiz, and a Male Juvenile". FBI. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- "Average Conditions Guaynabo". weather.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- J.D. (May 2, 2006). "Guaynabo". Link To Puerto Rico.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Post Office Location - GUAYNABO Archived 2010-03-15 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 19, 2010.

- "Post Office Location - CAPARRA HEIGHTS Archived 2010-03-15 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 19, 2010.

- "MDC Guaynabo Contact Information Archived 2009-05-07 at the Wayback Machine." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on January 12, 2010.

- Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General Archived 2013-01-15 at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- "GUAYNABO". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- "New hospital and medical building developing in Guaynabo" Caribbean Business Newspaper, Issued : 06/12/2008, By : LISA NIDO NYLUND

- "Avanza la cirugía de la columna" Primera Hora Newspaper, Alejandra M. Jover Tovarra - 10/02/2009

- "Guaynabo Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- "北米の補習授業校一覧" (). MEXT. January 2, 2003. Retrieved on April 6, 2015. (Puerto Rico) "(学校所在地) CALLEDELFOS #2119 ALTO APOLO GUAYNABO P.R 00969,U.S.A."

- "関係機関へのリンク" (Archive). The Japan School of Doha. Retrieved on March 31, 2015. "ポート・モレスビー補習授業校(2009年8月休校)" and "(ニューメキシコ)アルバカーキ補習授業校(休校)" and "(プエルトリコ)プエルトリコ補習授業校(2006年3月閉校)"