Lares, Puerto Rico

Lares (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈlaɾes], locally [ˈlaɾeʔ]) is a mountain town and municipality of Puerto Rico's central-western area. Lares is located north of Maricao and Yauco; south of Camuy, east of San Sebastián and Las Marias; and west of Hatillo, Utuado and Adjuntas. Lares is spread over 10 barrios and Lares Pueblo (Downtown Lares). It is part of the Aguadilla-Isabela-San Sebastián Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Lares

Municipio Autónomo de Lares | |

|---|---|

Town and Municipality | |

Lares City Hall in 2019 | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: Ciudad del Grito (The Town of The Cry), Altar de la Patria (High of the Fatherland), La Capital de la Montaña (Capital of the Mountains)[1] | |

| Anthem: "En las verdes montañas de Lares" (In the green mountains of Lares) | |

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Lares Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°17′42″N 66°52′43″W | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Founded | April 26, 1827 |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Fabián Arroyo Rodríguez[2] (PPD) |

| • Senatorial dist. | 5 - Ponce |

| • Representative dist. | 22 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 61.64 sq mi (159.6 km2) |

| • Land | 61.45 sq mi (159.2 km2) |

| • Water | .09 sq mi (0.2 km2) |

| Population (2020)[3] | |

| • Total | 28,105 |

| • Rank | 45th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 460/sq mi (180/km2) |

| Demonym | Lareños |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Codes | 00669, 00631 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

A city adorned with Spanish-era colonial-style churches and small downtown stores, Lares is located on a breezy area that is about 1.5 hours from San Juan by car.

Lares was the site of the 1868 El Grito de Lares (literally, The Cry of Lares, or Lares Revolt), an uprising brought on by pro-independence rebels who wanted Puerto Rico to gain its freedom from Spain. Even though it was soon extinguished it remains an iconic historical event in the history of the island.[4]

History

Lares was founded on April 26, 1827, by Francisco de Sotomayor and Pedro Vélez Borrero, who named the town after Amador de Lariz, a Spanish nobleman and one of its settlers.[5][6]

El Grito de Lares ("Cry of Lares") was a rebellion that began on September 23, 1868, against repression by Spain and has served as a symbol of Puerto Rico's fight for independence since.[7] Historian Fernando Picó described it thus:

This revolution was the biggest anti-Spanish manifestation in the history of the island and articulated the economic frustrations of nearly ruined landowners, the political project of the creoles, the rejection of coerced labor by the jornaleros (day laborers), and the emancipation hopes of the enslaved population.

— Fernando Picó, The Absent State[8]

The flag of Lares (the first Puerto Rican flag) is now considered by many Puerto Ricans to be the symbol of their independence movement. Initially developed to represent the island's struggle to gain its emancipation from Spain, the flag is now used by those supporting the independence of the island from the United States. The flag was displayed during the week of September 17 to 23 of 2018, at the Museum of History, Anthropology and Art located within the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras Campus, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of El Grito de Lares.[9]

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became a territory of the United States. In 1899, the United States Department of War conducted a census of Puerto Rico finding that the population of Lares was 20,883.[10]

Hurricane Maria on September 20, 2017, triggered numerous landslides in Lares. In many areas of Lares there were more than 25 landslides per square mile due to the significant amount of rainfall.[11][12] Puerto Rico se levanta (Puerto Rico will stand up) became the slogan used across the island to communicate the island would rise again.[13]

When the hurricane hit, many areas in the Municipal Cemetery of Lares were damaged by landslides. Total affected were about 5,000 burial plots, with the burial places shifting and some plots opened. In response, the municipality closed the cemetery to the public.[14][15] In early 2019, El Nuevo Día newspaper in Puerto Rico began listing the names of the cadavers that would be exhumed and moved to other cemeteries, a long and delicate process. On March 4, an update was given by Lares officials on how the issue was being handled.[16] On May 10, 2019, it was announced that a decision had been made to build a temporary wooden structure separating the affected area so that family members could visit the plots that were unaffected by the hurricane-triggered landslides.[17] The Bravo Family Foundation sent relief to Lares, in the immediate aftermath.[18]

The December 2019 and January 2020 Puerto Rico earthquakes caused 28 families in Lares to lose their homes.[19]

Geography

Lares is a mountainous municipality located in the central western part of the island of Puerto Rico. According to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, the municipality has a total area of 61.64 square miles (159.6 km2), of which 61.45 square miles (159.2 km2) is land and .09 square miles (0.23 km2) is water.[20]

Caves

There are 10 caves in Lares. Cueva Machos and Cueva Pajita are located in Callejones barrio.[21]

Barrios

Like all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Lares is divided into barrios. The municipal buildings, central square and large Catholic church are located near the center of the municipality, in a barrio referred to as "el pueblo".[22][23][24][25]

Sectors

Barrios (which are, in contemporary times, roughly comparable to minor civil divisions)[26] in turn are further subdivided into smaller local populated place areas/units called sectores (which means sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[27]

Special Communities

Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Lares: Castañer, Cerro Avispa, Comunidad Anón, Comunidad Arizona, Comunidad El Bajadero, Comunidad Peligro, Comunidad San Felipe, and Seburuquillo.[28][29]

Tourism

Landmarks and places of interest

- Callejones Site — NRHP listed

- Downtown Castañer and its former city hall[30]

- Hacienda Collazo

- Hacienda El Porvenir

- Hacienda Lealtad[31][32]

- Hacienda Los Torres — NRHP listed

- Heladería de Lares — ice cream parlor

- Mirador Mariana Bracetti

- Parque El Jíbaro

Festivals and events

Lares celebrates its patron saint festival in December. The Fiestas Patronales de San Jose is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[33][34] The festival has featured live performances by well-known artists such as Sie7e, and Ednita Nazario.[35]

Other festivals and events celebrated in Lares include:

- Banana Festival – June

- Lares Festival – September

- Rábano Estate Festival – October

- Almojábana Festival – October

Sports

Lares has a professional volleyball team called Patriotas de Lares (Lares Patriots) that have international players including: Brock Ullrich, Gregory Berrios, Ramon "Monchito" Hernandez, and Ariel Rodriguez. The Patriotas won 3 championships, in 1981, 1983 and 2002. In 1981 and 1983 they beat Corozal in the finals and in 2002 they beat Naranjito. Some of the local players were David Vera 1979, Rigoberto Guiyoti 1979, Modesto 1980, Luis Vera 1980, Carlos Vera 1980.

Economy

Lares' economy is primarily agricultural. Harvested products include bananas, coffee, oranges, and tomatoes.

Tourism also plays a significant role in the municipality's economy. The Heladeria de Lares (Lares Ice Cream Shop) is well known around Puerto Rico for its unorthodox selection of ice cream including; rice and beans-flavored ice cream.[36]

There was a large population exodus, out of Lares, after September 20, 2017, when Hurricane Maria struck the island.[37]

In 2016, Rural Opportunities Puerto Rico Inc. (ROPRI) in conjunction with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) completed the building of 24 (one-bedroom, two-bedroom and three-bedroom) units[38] in Lares, specifically for farmers (in Spanish: agricultores), and their families, to live and work. It is called Alturas de Castañer (Castañer Heights) and there the families work to grow coffee, bananas and other crops which are sold to markets, and restaurants nearby.[39]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 20,883 | — | |

| 1910 | 22,650 | 8.5% | |

| 1920 | 25,197 | 11.2% | |

| 1930 | 27,351 | 8.5% | |

| 1940 | 29,914 | 9.4% | |

| 1950 | 29,951 | 0.1% | |

| 1960 | 26,922 | −10.1% | |

| 1970 | 25,263 | −6.2% | |

| 1980 | 26,743 | 5.9% | |

| 1990 | 29,015 | 8.5% | |

| 2000 | 34,415 | 18.6% | |

| 2010 | 30,753 | −10.6% | |

| 2020 | 28,105 | −8.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[40] 1899 (shown as 1900)[41] 1910-1930[42] 1930-1950[43] 1960-2000[44] 2010[24] 2020[45] | |||

Like most of Puerto Rico, Lares population originated with the Taino Indians and then many immigrants from Spain settled the central highland, most prominently the Andalusian, Canarian and Extremaduran Spanish migration who formed the bulk of the Jibaro or white peasant stock of the island.[46] The Andalusian, Canarian and Extremaduran Spaniards also influenced much of the Puerto Rican culture which explains the use of Spanish and the Spanish architecture that can be found in the city.

Government

The mayor of Lares for fifteen years was Roberto Pagán Centeno and he resigned in late 2019.[47] José Rodríguez Ruiz began serving his term as mayor of Lares on January 20, 2020.[48][49] Rodríguez Ruiz belongs to the Hospitaller Order of Saint Lazarus.[50]

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district V, which is represented by two Senators. In 2020, Ramón Ruiz and Marially Gonzalez, from the Popular Democratic Party, were elected as District Senators.[51]

Education

The Héctor Hernández Arana Primary school is located in Lares.[52]

Symbols

The municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[53]

Flag

The origins of the municipality's flag can be traced back to the days of the failed 1868 revolt against Spanish rule known as the Grito de Lares. The flag is derived from the Dominican Republic flag of 1844-49 (reflecting the rebel leaders' dream to eventually join with the Dominican Republic and Cuba into one nation) and was knitted by Mariana Bracetti, a revolutionary leader, at the behest of Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances, the revolt's leader, who designed it. This flag is formed by a white Latin cross in the center. The width of the arms and base are equal to a third part of the latitude of the emblem. It has two quadrilaterals located above and two below the arms of the cross. The superior (top) ones are blue and the inferior (bottom) ones red. A five-point white star is located in the center of the left superior (top) quadrilateral.[54]

Coat of arms

A silver cross is centered on and extends across the shield from side to side and top to bottom; it has blue top quadrants and red bottom quadrants; it has a five pointed silver star in the upper left quadrant. A chain surrounds the shield. The seal is same coat of arms with a scroll and a ribbon in a semicircle with the words: "Lares Ciudad del Grito."[54]

Notable Lareños

- Singer, composer and Virtuoso Guitarist Jose Feliciano who wrote and sang the Feliz Navidad Song, was born in Lares on September 8, 1945

- Lolita Lebrón was a Puerto Rican nationalist who was convicted of attempted murder and other crimes in 1954 and freed from prison in 1979 after being granted clemency by President Jimmy Carter.

- Denise Quiñones - Miss Universe 2001

- Luis Hernández Aquino[56]

- Odilio González (born March 5, 1937), known by his stage name El Jibarito de Lares, is a Puerto Rican singer, guitarist and music composer who has been singing and composing for more than 65 years.

Gallery

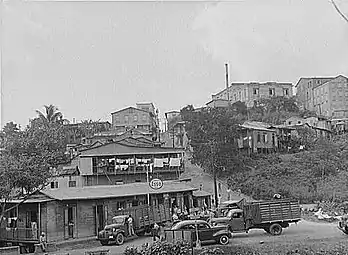

Lares in 1942

Lares in 1942 "Lares, Puerto Rico. A street in the town" (Photograph by Jack Delano, 1941)

"Lares, Puerto Rico. A street in the town" (Photograph by Jack Delano, 1941) Lares se levanta sign seen in Lares in June 2019

Lares se levanta sign seen in Lares in June 2019 Puerto Rico Highway 111 East near 129 junction in Lares

Puerto Rico Highway 111 East near 129 junction in Lares Catedral de Lares (Lares Cathedral) in July 2007

Catedral de Lares (Lares Cathedral) in July 2007

References

- "Lares Municipality - Municipalities | EnciclopediaPR". Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Lares conmemora los 154 años del Grito de Lares" [Lares commemorates the 154th anniversary of the Grito de Lares]. Periódico El Sol de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Pérez Hernández Group, LLC. September 12, 2022. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- Bureau, US Census. "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "The Cry of Lares". Progreso Weekly Inc. September 22, 2013. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- "History and foundation of Lares". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- "Lares: Ciudad de cielos abiertos". nuevaisla.com (in Spanish). SG Communications. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- "Historia de la insurrección de Lares, precedida de una reseña de los trabajos separatistas que se vienen haciendo en la isla de Puerto-Rico desde la emancipación de las demás posesiones hispano-ultramarinas, y seguida de todos los documentos á ella referentes;". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- Picó, Fernando (March 13, 2008). "The Absent State". In Negrón-Muntaner, Frances (ed.). None of the Above:Puerto Ricans in the Global Era. New Directions in Latino American Cultures Ser. p. 23. ISBN 9781403962454. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- "Exhiben en UPR bandera de Lares con 150 años". Primera Hora. September 16, 2018. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office (in Spanish). Imprenta del Gobierno. p. 160. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico" (PDF). USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Newkirk II, Vann R. (September 20, 2018). "The Situation in Puerto Rico Is Untenable". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- "Las tumbas quedan expuestas en el camposanto de Lares". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Florida, Adrian (December 6, 2018). "'My Father Is In There': Anguish Builds In Puerto Rico Mountains Over Decimated Tombs". NPR. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "Informe sobre el Cementerio Municipal Post-Maria". FaceBook (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- "Regalo de madres para familiares de difuntos en Lares". Primera Hora. May 10, 2019. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "María, un nombre que no vamos a olvidar. El huracán sacudió los cimientos del cementerio de Lares" [Maria, a name we will never forget. The hurricane shook the foundations of the Lares cemetery]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). June 13, 2019. Archived from the original on September 11, 2022. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- "Refugiadas 28 familias en Lares tras temblor 5.9 del sábado". Primera Hora (in Spanish). January 12, 2020. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- "Lares Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Lares: Ciudad de cielos abiertos". Nueva Isla (in Spanish). SG Communications. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- Picó, Rafael; Buitrago de Santiago, Zayda; Berrios, Hector H. (1969). Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social, por Rafael Picó. Con la colaboración de Zayda Buitrago de Santiago y Héctor H. Berrios. San Juan Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Puerto Rico,1969. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- Gwillim Law (May 20, 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- "Map of Lares at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "PRECINTO ELECTORAL LARES 053" (PDF). Comisión Estatal de Elecciones (in Spanish). PR Government. June 14, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza:Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (1st ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). August 8, 2011. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Brugueras, Melba (August 22, 2015). "Conoce cómo se vive en Castañer". Primera Hora. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- "Un pedacito de Hacienda Lealtad en el RUM". Primera Hora. March 21, 2019. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "Compañía de Turismo brinda certificación agroturística a Hacienda Lealtad". October 18, 2016. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "Puerto Rico Festivales, Eventos y Actividades en Puerto Rico". Puerto Rico Hoteles y Paradores (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- J.D. (May 2, 2006). "Lares". Link To Puerto Rico.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Tradicionales Fiestas de Pueblo 2013". sondeaquiprnet. El Gobierno Municipal de Lares. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- "Histórica Heladería de Lares reabrirá sus puertas". El Nuevo Dia. February 1, 2017. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Robles, Frances (July 16, 2017). "Exodus From a Historic Puerto Rican Town, With No End in Sight". NYTimes. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "Alturas De Castaner - Castaner PR Multi-Family Housing Rental". housingapartments.org. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- "A Community for Agricultores in Puerto Rico". www.usda.gov. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Report of the Census of Porto Rico 1899". War Department, Office Director Census of Porto Rico. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930, 1920, and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities, Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Bureau, US Census. "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- Hernández, Miguel. "Brief History of the Canarian Migration to Spanish America". Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- "El alcalde de Lares Roberto Pagán Centeno presentó su renuncia | el Nuevo Día". November 19, 2019. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- Marrero, Juan. "José Rodríguez es certificado nuevo alcalde de Lares por el PNP". Metro. Archived from the original on January 20, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "PNP confirmará a José Rodríguez como alcalde de Lares". Primera Hora. January 19, 2020. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Puerto Rico: Our Knight of Grace Jose Rodriguez elected Mayor of Lares". Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General Archived 2013-01-15 at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- "Escuela Héctor Hernández Arana (18226)". Dept. of Education of Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- "LARES". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). August 6, 2020. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Lares Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Rodríguez León O. P, Mario A. (September 15, 2014). "The Poetry of Luis Hernández Aquino". Enciclopedia PR. Enciclopedia PR. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.