Guests of the Nation

"Guests of the Nation" is a short story written by Frank O'Connor, first published in 1931, portraying the execution of two British soldiers being held captive by the Irish Republican Army during the War for Independence. The story is split into four sections, each section taking a different tone. The first reveals a real sense of camaraderie between the IRA guards and the two English prisoners. With the two Englishmen being killed, the final lines of the story describe the nauseating effect this has on the Irishmen.

| "Guests of the Nation" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Frank O'Connor | |

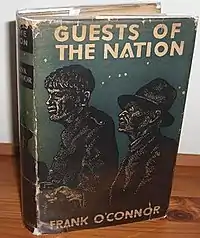

First UK edition of collection | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Language | English |

| Publication | |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

| Publication date | 1931 |

Neil McKenzie's stage adaptation of the story received a 1958 Obie Award.

Plot summary

The story opens with two British Army enlisted men, Privates Hawkins and Belcher, being held prisoner by the Irish Volunteers near Ballinasloe, County Galway during the Irish War of Independence. They all play cards and argue about politics, religion, atheism, girls, socialism, and capitalism. The group is housed in the cottage of a fine old lady, who in addition to tending the house engages the men in arguments. She is a religious woman and quick to scold the men if they displease her.

Bonaparte, the narrator, and his compatriot, Noble, become friends with the English soldiers. Jeremiah Donovan, the third Irishman, remains aloof from the others. He is the Commanding Officer of the local IRA Flying Column. One evening Donovan reminds Bonaparte and Noble that the two Englishmen are not being held as prisoners, but as hostages. He informs them that if the Crown security forces kill any of their IRA prisoners, the execution of Hawkins and Belcher will take place in retaliation. This news disturbs Bonaparte and he has difficulty facing his prisoners the next day.

A few days later, Feeney, a Brigade intelligence officer for the IRA, arrives with the news that four Irish prisoners have just been brutally tortured and shot. Hawkins and Belcher are to be duly executed that evening. It is left to Donovan to tell Bonaparte and Noble. Private Hawkins, an atheist and self-described Bolshevik who has been mocking his captors' faith in Catholicism, notices Bonaparte and Noble's sadness and, thinking they are doubting their religion, Hawkins continues his taunts.

In order to get the two hostages out of the cottage, Donovan makes up a story about a transfer; on the way down a path into a nearby peat bog, he tells them the truth. At first, Private Hawkins does not believe him. But as the truth settles in, Hawkins tries to convince Donovan not to kill them, arguing that, if their positions were reversed, he would never shoot “a pal.” Donovan replies by angrily describing the British Army's torture and murder of the four Irish prisoners. In response, Private Hawkins asks to be allowed to desert the British Army and fight instead as an Irish republican, saying that he sees no difference between the two causes.

Bonaparte has misgivings about executing the two men and hopes that they attempt to escape, because he knows that he would let them go. He realizes that he now regards them as men, rather than as part of the anonymous enemy. Despite Private Hawkins’ pleadings, Donovan shoots Hawkins in the back of the head.

As Private Belcher fumbles to tie a blindfold around his own eyes before he is shot, he notices that Hawkins is not dead and tells Bonaparte to “give him another.” Unlike Hawkins, Belcher displays an inordinate amount of dignity and composure, even as he calmly talks about how hard his death will be for his wife in England. Donovan then shoots Belcher in the head. The group digs a shallow grave in the bog and buries the two Englishmen. Feeney leaves and the men return to the cottage, where the old woman asks what they have done with the Englishmen. No answer is given, but she immediately understands and falls sobbing to her knees to pray for both men's souls. Noble does the same. Bonaparte leaves the cottage and looks up at the night sky feeling small and lost. He says that he never felt the same way about the war ever again.

Characters

- Bonaparte

- Noble

- Jeremiah Donovan

- Hawkins

- Belcher

- The Old Woman

• Guests Of The Nation is an ironic/sarcastic description of British Army hostages seized in the Irish war of Independence by Irish republicans.

• Belcher: A large Englishman who is one of the hostages, he was the quieter of the two who ingratiated himself with the old woman of the house by helping her with her daily chores. Belcher had made her his friend for life. Belcher on realising his fate seemed to accept it as “whatever unforeseen thing he’d always been waiting for had come at last”. His sense of organisation sees him preparing his own blindfold for his execution. His courage and generosity sees him request of his executioners that they finish off Hawkins first before he meets his own fate. This is further demonstrated in Belcher's acknowledging to his executioners that they are only doing their duty. Belcher's whole character and personality is found in his last statement. His lover “went away with another fellow and took the kid with her. I like the feeling of a home, as you may have noticed, but I couldn't start another again after that”.

• Hawkins: The second hostage made his captors look like fools when he showed that he knew the country better than they did. Hawkins knew Mary Brigid O’Connell and had learned to dance traditional dances such as the Walls of Limerick. Hawkins had too much old talk and as a result lost at cards. He always argued with Noble into the early hours. He worried Noble about religion with a string of questions that would "puzzle a cardinal". He had a deplorable tone and he could throw bad language into any conversation. A communist and agnostic, Hawkins always argued with Noble about capitalism and religion. When it came to his execution Hawkins could not believe his fate and thought his friends were joking. Hawkins's terror at the prospect of death highlights the futility of the conflict in terms of humanity and the friendships that developed between the captors and hostages. The execution of Hawkins provides a chilling climax to this episode.

• Jeremiah Donovan: He is not the narrator. Irish soldier who does not like the prisoners. Donovan reddens when spoken to and tends to look down at his feet, yet when it comes time to execute the Englishmen, he is strangely energised and excited. Donovan believes in a questionable interpretation of duty to his country, of which he constantly speaks and which he cites as justification for the execution. When Irish prisoners are executed by the English, it becomes clear that he unidimensionally believes in taking an eye for an eye. Donovan is the character who commences the act of killing in the execution scene, though it is the narrator's firearm that is first mentioned by the narrator.

• Noble: A young volunteer who along with Bonaparte guarded the hostages. Noble’s character and personality is expressed in the story in his exchanges with Hawkins. Noble is a devout Catholic who had a brother (a priest) and worries greatly about the force and vigour of Hawkins' terrible arguments. Noble shows his humanity in not wanting to be part of a deception, telling the hostages that they were being shifted again. Yet he understood his duty, and undertook the order of preparing the graves at the far end of the bog.

• Bonaparte: The narrator of this story. It’s not clear from the story the relationship between Bonaparte and the author, but given O’Connor’s role in the I.R.A some comparisons may well be drawn. Bonaparte has the responsibility of telling a terrible and chilling story about a war of independence. These stories are a testament to the butchery and futility of war. The last paragraph of the story best describes the effect this episode had on both Bonaparte and Noble. Communicating on what happened in the bog to the old lady without saying what they did, the description by Noble of the little patch of bog with the Englishmen stiffening into it, and Bonaparte “very lost and lonely like a child, a stray in the snow. And anything that happened to me afterwards, I never felt the same about again."

"Guests of the Nation" is the title story of the 1931 Frank O'Connor short story collection of the same name.[1] This collection includes:

- "Guests of the Nation"

- "Attack"

- "Jumbo's Wife"

- "Nightpiece with Figures"

- "September Dawn"

- "Machinegun Corps in Action"

- "Laughter"

- "Jo"

- "Alec"

- "Soiree Chez une Belle Jeune Fille"

- "The Patriarch"

- "After Fourteen Years"

- "The Late Henry Conran"

- "The Sisters"

- "The Procession of Life"

Influences

Isaac Babel's Red Cavalry influenced O'Connor especially in this story "Guests of the Nation".[2]

Adaptations

"Guests of the Nation" was made into a silent film in 1934, screenplay by Mary Manning, directed by Denis Johnston, and including Barry Fitzgerald and Cyril Cusack. Guests of the Nation at IMDb

The story was adapted for the stage by Neil McKenzie.[3] It received a 1958 Obie Award for best one-act play.[4]

The Crying Game, directed by Neil Jordan, is partly based on O'Connor's short story.

References

- Frank O’Connor. Guests of the Nation. London/New York: Macmillan, 1931.

- Kratkaya Literaturnaya Entsiklopedyia 5. Moscow: Sovetskaya Inceklopedia. 1968.

- "Guests of the Nation". Dramatists Play Service. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Search the Obies". Village Voice. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

External links

- O'Connor, Frank. "Frank O´Connor, Guests of the Nation". Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- Guests of the Nation at the Internet Off-Broadway Database