Dracunculiasis

Dracunculiasis, also called Guinea-worm disease, is a parasitic infection by the Guinea worm, Dracunculus medinensis. A person typically becomes infected by drinking water containing water fleas infected with guinea worm larvae. The larvae penetrate the digestive tract and escape into the body where the females and males mate. Around a year later, the adult female migrates to an exit site – usually a lower limb – and induces an intensely painful blister on the skin. The blister eventually bursts to form an intensely painful wound, out of which the worm slowly crawls over several weeks. The wound remains painful throughout the worm's emergence, disabling the infected person for the three to ten weeks it takes the worm to emerge. During this time, the open wound can become infected with bacteria, leading to death in around 1% of cases.[2]

| Dracunculiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| |

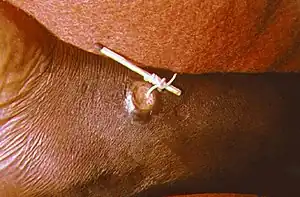

| Using a matchstick to wind up and remove a guinea worm from the leg of a human | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Painful blister that a long white string-like worm slowly crawls out of |

| Usual onset | One year after exposure |

| Causes | Guinea worm-infected water fleas |

| Prevention | Preventing those infected from putting the wound in drinking water, treating contaminated water |

| Treatment | Slowly extracting worm, supportive care, oral metronidazole to relieve symptoms and to prevent inflammation and abscess formation if the worm breaks |

| Frequency | 13 cases worldwide (2022)[1] |

| Deaths | ~1% of cases |

There is no known antihelminthic agent to expel the Guinea worm. Instead, the mainstay of treatment is the careful wrapping of the emerging worm around a small stick or gauze to encourage its exit. Each day, a few more centimeters of the worm emerge, and the stick is turned to maintain gentle tension. Too much tension can break and kill the worm in the wound, causing severe pain and swelling at the ulcer site. Dracunculiasis is a disease of extreme poverty, occurring in places with poor access to clean drinking water. Prevention efforts center on filtering drinking water to remove water fleas, as well as public education campaigns to discourage people from soaking their emerging worms in sources of drinking water.

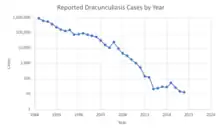

Humans have had dracunculiasis since at least 1,000 BCE, and accounts consistent with dracunculiasis appear in surviving documents from physicians of antiquity. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, dracunculiasis was widespread across much of Africa and South Asia, affecting as many as 48 million people per year. The effort to eradicate dracunculiasis began in the 1980s following the successful eradication of smallpox. By 1995, every country with endemic dracunculiasis had established a national eradication program. In the ensuing years, dracunculiasis cases have dropped precipitously, with only a few dozen annual cases worldwide since 2015. Fifteen previously endemic countries have been certified to have eradicated dracunculiasis, leaving the disease endemic in just four countries: Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan. A record low 13 cases of dracunculiasis were reported worldwide in 2022.[1] If the eradication program succeeds, dracunculiasis will become the second human disease known to have been eradicated, after smallpox.

Signs and symptoms

_removal_(MIS_67-1563-1)%252C_National_Museum_of_Health_and_Medicine_(4951692786).jpg.webp)

The first signs of dracunculiasis occur around a year after infection, as the full-grown female worm prepares to leave the infected person's body.[3] As the worm migrates to its exit site – typically the lower leg, though they can emerge anywhere on the body – some people have allergic reactions, including hives, fever, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[4] Upon reaching its destination, the worm forms a fluid-filled blister under the skin.[5] Over 1–3 days, the blister grows larger, begins to cause severe burning pain, and eventually bursts leaving a small open wound.[3] The wound remains intensely painful as the worm slowly emerges over several weeks to months.[6]

In an attempt to alleviate the excruciating burning pain, the host will nearly always attempt to submerge the affected body part in water. When the worm is exposed to water, it spews a white substance containing thousands of larvae.[5] As the worm emerges, the open blister often becomes infected with bacteria, resulting in redness and swelling, the formation of abscesses, or in severe cases gangrene, sepsis or lockjaw.[7][2] When the secondary infection is near a joint (typically the ankle), the damage to the joint can result in stiffness, arthritis, or contractures.[2][8]

Infected people commonly harbor multiple worms – with an average 1.8 worms per person;[9] up to 40 at a time – which will emerge from separate blisters at the same time.[4] 90% of worms emerge from the legs or feet. However, worms can emerge from anywhere on the body.[4]

Cause

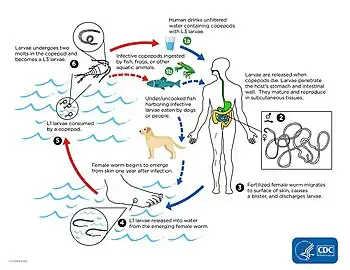

Dracunculiasis is caused by infection with the roundworm Dracunculus medinensis.[3] D. medinensis larvae reside within small aquatic crustaceans called copepods or water fleas. When humans drink the water, they can unintentionally ingest infected copepods. During digestion the copepods die, releasing the D. medinensis larvae. The larvae exit the digestive tract by penetrating the stomach and intestine, taking refuge in the abdomen or retroperitoneal space.[10] Over the next two to three months the larvae develop into adult male and female worms. The male remains small at 4 cm (1.6 in) long and 0.4 mm (0.016 in) wide; the female is comparatively large, often over 100 cm (39 in) long and 1.5 mm (0.059 in) wide.[5] Once the worms reach their adult size they mate, and the male dies.[4] Over the ensuing months, the female migrates to connective tissue or along bones, and continues to develop.[4]

About a year after the initial infection, the female migrates to the skin, forms an ulcer, and emerges. When the wound touches freshwater, the female spews a milky-white substance containing hundreds of thousands of larvae into the water.[4][6] Over the next several days as the female emerges from the wound, she can continue to discharge larvae into surrounding water.[6] The larvae are eaten by copepods, and after two to three weeks of development, they are infectious to humans again.[11]

Diagnosis

Dracunculiasis is diagnosed by visual examination – the thin white worm emerging from the blister is unique to this disease.[12] Dead worms sometimes calcify and can be seen in the subcutaneous tissue by X-ray.[2][12]

Treatment

There is no medicine to kill D. medinensis or prevent it from causing disease once within the body.[13] Instead, treatment focuses on slowly and carefully removing the worm from the wound over days to weeks.[14] Once the blister bursts and the worm begins to emerge, the wound is soaked in a bucket of water, allowing the worm to empty itself of larvae away from a source of drinking water.[14] As the first part of the worm emerges, it is typically wrapped around a piece of gauze or a stick to maintain steady tension on the worm, encouraging its exit.[14] Each day, several centimeters of the worm emerge from the blister, and the stick is wound to maintain tension.[4] This is repeated daily until the full worm emerges, typically within a month.[4] If too much pressure is applied at any point, the worm can break and die, leading to severe swelling and pain at the site of the ulcer.[4]

Treatment for dracunculiasis also tends to include regular wound care to avoid infection of the open ulcer while the worm is leaving. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends cleaning the wound before the worm emerges. Once the worm begins to exit the body, the CDC recommends daily wound care: cleaning the wound, applying antibiotic ointment, and replacing the bandage with fresh gauze.[14] Painkillers like aspirin or ibuprofen can help ease the pain of the worm's exit.[4][14]

Outcomes

Dracunculiasis is a debilitating disease, causing substantial disability in around half of those infected.[2] People with worms emerging can be disabled for the three to ten weeks it takes the worms to fully emerge.[2] When worms emerge near joints, the inflammation around a dead worm, or infection of the open wound can result in permanent stiffness, pain, or destruction of the joint.[2] Some people with dracunculiasis have continuing pain for 12 to 18 months after the worm has emerged.[4] Around 1% of dracunculiasis cases result in death from secondary infections of the wound.[2]

When dracunculiasis was widespread, it would often affect entire villages at once.[8] Outbreaks occurring during planting and harvesting seasons severely impair a community's agricultural operations – earning dracunculiasis the moniker "empty granary disease" in some places.[8] Communities affected by dracunculiasis also see reduced school attendance as children of affected parents must take over farm or household duties, and affected children may be physically prevented from walking to school for weeks.[15]

Infection does not create immunity, so people can repeatedly experience dracunculiasis throughout their lives.[16]

Prevention

.jpg.webp)

There is no vaccine for dracunculiasis, and once infected with D. medinensis there is no way to prevent the disease from running its full course.[13] Consequently, nearly all effort to reduce the burden of dracunculiasis focuses on preventing the transmission of D. medinensis from person to person. This is primarily accomplished by filtering drinking water to physically remove copepods. Nylon filters, finely woven cloth, or specialized filter straws are all effective means of copepod removal.[4][17] Sources of drinking water can be treated with the larvicide temephos, which kills copepods,[18] and contaminated water can also be treated via boiling.[19] Where possible, open sources of drinking water are replaced by deep wells that can serve as new sources of clean water.[18] Public education campaigns inform people in affected areas how dracunculiasis spreads and encourage those with the disease to avoid soaking their wounds in bodies of water that are used for drinking.[4]

Epidemiology

Dracunculiasis is nearly eradicated, with just 15 cases reported worldwide in 2021[20] and 13 in 2022.[21] This is down from 27 cases in 2020, and dramatically less than the estimated 3.5 million annual cases in 20 countries in 1986 – the year the World Health Assembly called for dracunculiasis' eradication.[20][22] Dracunculiasis remains endemic in just four countries: Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan.[23]

Dracunculiasis is a disease of extreme poverty, occurring in places where there is poor access to clean drinking water.[24] Cases tend to be split roughly equally between males and females, and can occur in all age groups.[25] Within a given place, dracunculiasis risk is linked to occupation; people who farm or fetch drinking water are most likely to be infected.[25]

Cases of dracunculiasis have a seasonal cycle, though the timing varies by location. Along the Sahara desert's southern edge, cases peak during the mid-year rainy season (May–October) when stagnant water sources are more abundant.[25] Along the Gulf of Guinea, cases are more common during the dry season (October–March) when flowing water sources dry up.[25]

History

Dracunculiasis has been with humans for at least 3,000 years, as the remnants of a guinea worm infection have been found in the mummy of a girl entombed in Egypt around 1,000 BCE.[26] Diseases consistent with the effects of dracunculiasis are referenced by writers throughout antiquity. The disease of "fiery serpents" that plagues the Hebrews in the Old Testament (around 1250 BCE) is often attributed to dracunculiasis.[24][26][note 1] Plutarch's Symposiacon refers to a (lost) description of a similar disease by the 2nd century BCE writer Agatharchides concerning a "hitherto unheard of disease" in which "small worms issue from [people's] arms and legs ... insinuating themselves between the muscles [to] give rise to horrible sufferings".[26] Rufus of Ephesus, who lived at the time of Emperor Trajan, is the first medical author to describe the disease, which he claims to have observed in Egypt, and to observe its spread through water: In Arabia there is a disease called ‘Ophis’, which in Greek means tendon (νεῦρον). The animal is thick like a string (of the lyra) and coils in the flesh like a snake, mainly in the thigh and calf regions, although also in other parts of the body. I saw an Arab in Egypt who had this disease, and every time it [the worm] wanted to explode, he felt pain and had fever. The man now had this apparition on his calf, but his servant in the navel region and another woman in the loin region. But when I asked if this disease was common among Arabs, people said that both Arabs and many foreigners who came there and were affected when they drank the water suffered from this disease. Because this is mainly the cause (Quaest. med. 65-69).[27] Many of antiquity's famous physicians also write of diseases consistent with dracunculiasis, including Galen, Rhazes, and Avicenna; though there was some disagreement as to the nature of the disease, with some attributing it to a worm, while others considered it to be a corrupted part of the body emerging.[26] In his 1674 treatise on dracunculiasis, Georg Hieronymous Velschius first proposed that the Rod of Asclepius, a common symbol of the medical profession, depicts a recently extracted guinea worm.[26]

Carl Linnaeus included the guinea worm in his 1758 edition of Systema Naturae, naming it Gordius medinensis.[26] The name medinensis refers to the worm's longstanding association with the city of Medina, with Avicenna writing as early as his The Canon of Medicine (published in 1025) "The disease is commonest at Medina, whence it takes its name".[26] In Johann Friedrich Gmelin's 13th edition of Systema Naturae (1788), he renamed the worm Filaria medinensis, leaving Gordius for free-living worms.[26] Henry Bastian authored the first detailed description of the worm itself, published in 1863.[26][28] The following year, in his book Entozoa, Thomas Spencer Cobbold used the name Dracunculus medinensis, which was enshrined as the official name by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in 1915.[26] Despite longstanding knowledge that the worm was associated with water, the lifecycle of D. medinensis was the topic of protracted debate.[29] Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko filled a major gap with his 1870 publication describing that D. medinensis larvae can infect and develop inside Cyclops crustaceans.[30][31][note 2] The next step was shown by Robert Thomson Leiper, who described in a 1907 paper that monkeys fed D. medinensis-infected Cyclops developed mature guinea worms, while monkeys directly fed D. medinensis larvae did not.[30]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, dracunculiasis was widespread across nearly all of Africa and South Asia, though no exact case counts exist from the pre-eradication era.[25] In a 1947 article in the Journal of Parasitology, Norman R. Stoll used rough estimates of populations in endemic areas to suggest that there could be as many as 48 million cases of dracunculiasis per year.[32][33] In 1976, the WHO estimated the global burden at 10 million cases per year.[33] Ten years later, as the eradication effort was beginning, the WHO estimated 3.5 million cases per year worldwide.[34]

Eradication

The campaign to eradicate dracunculiasis began at the urging of the CDC in 1980.[35] Following smallpox eradication (last case in 1977; eradication certified in 1981), dracunculiasis was considered an achievable eradication target since it was relatively uncommon and preventable with only behavioral changes.[36] In 1981, the steering committee for the United Nations International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (a program to improve global drinking water during the decade from 1981 to 1990) adopted the goal of eradicating dracunculiasis as part of their efforts.[37] The following June, an international meeting termed "Workshop on Opportunities for Control of Dracunculiasis" concluded that dracunculiasis could be eradicated through public education, drinking water improvement, and larvicide treatments.[37] In response, India began its national eradication program in 1983.[37] In 1986, the 39th World Health Assembly issued a statement endorsing dracunculiasis eradication and calling on member states to craft eradication plans.[36] The same year, The Carter Center began collaborating with the government of Pakistan to initiate its national program, which then launched in 1988.[37] By 1996, national eradication programs had been launched in every country with endemic dracunculiasis: Ghana and Nigeria in 1989; Cameroon in 1991; Togo, Burkina Faso, Senegal, and Uganda in 1992; Benin, Mauritania, Niger, Mali, and Côte d'Ivoire in 1993; Sudan, Kenya, Chad, and Ethiopia in 1994; Yemen and the Central African Republic in 1995.[36][38]

Each national eradication program had three phases. The first phase consisted of a nationwide search to identify the extent of dracunculiasis transmission and develop national and regional plans of action. The second phase involved the training and distribution of staff and volunteers to provide public education village-by-village, surveil for cases, and deliver water filters. This continued and evolved as needed until the national burden of disease was very low. Then in a third phase, programs intensified surveillance efforts with the goal of identifying each case within 24 hours of the worm emerging and preventing the person from contaminating drinking water supplies. Most national programs offered voluntary in-patient centers, where those affected could stay and receive food and care until their worms were removed.[39]

In May 1991, the 44th World Health Assembly called for an international certification system to verify dracunculiasis eradication country-by-country.[37] To this end, in 1995 the WHO established the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication (ICCDE).[40] Once a country reports zero cases of dracunculiasis for a calendar year, the ICCDE considers that country to have interrupted guinea worm transmission, and is then in the "precertification phase".[41] If the country repeats this feat with zero cases in each of the next three calendar years, the ICCDE sends a team to the country to assess the country's disease surveillance systems and to verify the country's reports.[41] The ICCDE can then formally recommend the WHO Director-General certify a country as free of dracunculiasis.[40]

Since the initiation of the global eradication program, the ICCDE has certified 15 of the original endemic countries as having eradicated dracunculiasis: Pakistan in 1997; India in 2000; Senegal and Yemen in 2004; the Central African Republic and Cameroon in 2007; Benin, Mauritania, and Uganda in 2009; Burkina Faso and Togo in 2011; Côte d'Ivoire, Niger, and Nigeria in 2013; and Ghana in 2015.[23]

| Date | South Sudan | Mali | Ethiopia | Chad | Angola | Cameroon[N 1] | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 2011 | 1,028[42] | 12[42] | 8[42] | 10[42] | 0 | 0 | 1,058 |

| 2012 | 521[43] | 7[43] | 4[43] | 10[43] | 0 | 0 | 542 |

| 2013 | 113[44] | 11[44] | 7[44] | 14[44] | 0 | 0 | 148[N 2] |

| 2014 | 70[45] | 40[45] | 3[45] | 13[45] | 0 | 0 | 126 |

| 2015 | 5[46] | 5[46] | 3[46] | 9[46] | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| 2016 | 6[47] | 0[47] | 3[47] | 16[47] | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| 2017 | 0[48] | 0[48] | 15[48] | 15[48] | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| 2018 | 10[49] | 0[49] | 0[49] | 17[49] | 1[49] | 0 | 28 |

| 2019 | 4[50] | 0[50] | 0[50] | 48[50] | 1[50] | 1[50] | 54 |

| 2020 | 1[51] | 1[51] | 11[51] | 12[51] | 1[51] | 1[51] | 27 |

| 2021 | 4[52] | 2[52] | 1[52] | 8[52] | 0[52] | 0[52] | 15 |

| 2022 | 5[53] | 0[53] | 1[53] | 6[53] | 0[53] | 0[53] | 13[N 3] |

| 2023 (through September) | 0[54] | 0[54] | 0[54] | 5[54] | 0[54] | 1[54] | 6 |

Other animals

In addition to humans, D. medinensis can infect dogs.[55] Infections of domestic dogs have been particularly common in Chad, where they helped reignite dracunculiasis transmission in 2010.[56] Dogs are thought to be infected by eating a paratenic host, likely a fish or amphibian.[57] As with humans, prevention efforts have focused on preventing infection by encouraging people in affected areas to bury fish entrails as well as to identify and tie up dogs with emerging worms so that they cannot access drinking water sources until after the worms have emerged.[57] Domestic ferrets can be infected with D. medinensis in laboratory settings, and have been used as an animal disease model for human dracunculiasis.[58]

Different Dracunculus species can infect snakes, turtles, and other mammals. Animal infections are most widespread in snakes, with nine different species of Dracunculus described in snakes in the United States, Brazil, India, Vietnam, Australia, Papua New Guinea, Benin, Madagascar, and Italy.[55][59] The only other reptile affected is the snapping turtle with infected common snapping turtles described in several U.S. states, and a single infected South American snapping turtle described in Costa Rica.[60] Infections of other mammals are limited to the Americas. Raccoons in the U.S. and Canada are most widely impacted, particularly by D. insignis; however, Dracunculus worms have also been reported in American skunks, coyotes, foxes, opossums, domestic dogs, domestic cats, and (rarely) muskrats and beavers.[61][62]

Notes

- This theory, put forth by Friedrich Küchenmeister in 1855, would make the Book of Numbers passage "Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died" among the oldest records of dracunculiasis. The contention that this passage refers to dracunculiasis is oft-repeated, though not universally held.[26]

- Fedchenko suggested that this discovery was serendipitous based on his observations of many waterborne animals. However, Rudolf Leuckart claimed that he had advised Fedchenko to investigate Cyclops due to the similarity between D. medinensis and the fish parasite Cucullanus elegans, the life cycle of which Leuckart had described in 1865.[30]

- Imported from Chad.

- Including 3 exported to Sudan.

- Including 1 imported from Chad in Central African Republic.

References

- "Global Eradication Campaign". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 January 2023. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- Despommier et al. 2019, p. 288.

- "Guinea Worm Disease Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Spector & Gibson 2016, p. 110.

- Despommier et al. 2019, p. 287.

- Hotez 2013, p. 67.

- "Guinea Worm – Disease". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Hotez 2013, p. 68.

- Greenaway 2004, "Clinical manifestations".

- "Guinea Worm – Biology". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- Despommier et al. 2019, pp. 287–288.

- Pearson RD (September 2020). "Dracunculiasis". Merck & Co. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Management of Guinea Worm Disease". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Ruiz-Tiben & Hopkins 2006, Section 4.2 "Socio-Economic Impact".

- Callahan et al. 2013, Introduction.

- Despommier et al. 2019, p. 289.

- Spector & Gibson 2016, p. 111.

- Hopkins, D. R.; Azam, M.; Ruiz-Tiben, E.; Kappus, K. D. (2 September 1995). "Eradication of dracunculiasis from Pakistan". Lancet. 346 (8975): 621–624. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91442-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 7651010. S2CID 35640613. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- WHO 2022, Figure 1.

- "Guinea worm disease could be second ever human illness to be eradicated". The Guardian. 25 January 2023. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- Despommier et al. 2019, p. 285.

- "Year in which countries certified". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- Spector & Gibson 2016, p. 109.

- Ruiz-Tiben & Hopkins 2006, Section 4. "Epidemiology".

- Grove 1990, pp. 693–698.

- Simonetti, O.; Zerbato, V.; Di Bella, S.; Luzzati, R.; Cavalli, F. (1 June 2023). "Infezioni in Medicina" (PDF). Le Infezioni in Medicina. 31 (2): 257–264. doi:10.53854/liim-3102-15. PMC 10241402. PMID 37283632.

- Bastian HC (November 1863). "On the structure and nature of the Dracunculus, or Guineaworm". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 24 (2): 101–134. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1863.tb00155.x. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- Grove 1990, pp. 698–702.

- Grove 1990, pp. 702–706.

- Fedchenko (Федченко), Alexei (Алексей) (1870). "О строении и размножении ришты (Filaria medinensis L.)" [On the structure and reproduction of the Guinea worm (Filaria medinensis L.)]. Известия Императорского Общества Любителей Естествознания, Антропологии и Этнографии [News of the Imperial Society of Devotees of Natural Science, Anthropology and Ethnography (Moscow)] (in Russian). 8 (1): 71–82. English translation: Fedchenko, AP (1971). "Concerning the structure and reproduction of the guinea-worm (Filaria medinensis L.)". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 20 (4): 511–523. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.511.

- Stoll NR (February 1947). "This wormy world". Journal of Parasitology. 33 (1): 1–18. JSTOR 3273613. PMID 20284977.

- Biswas et al. 2013, "Decision to Eradicate".

- "Dracunculiasis – Global surveillance summary, 1" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. World Health Organization (19). 10 May 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- Hopkins et al. 2018, Introduction.

- Hotez 2013, p. 69.

- Ruiz-Tiben & Hopkins 2006, Section 5. "Eradication Campaign".

- Ruiz-Tiben & Hopkins 2006, Table 1.

- Ruiz-Tiben & Hopkins 2006, Section 5.7 "Strategy for Eradication".

- Biswas et al. 2013, Section "Certification of eradication".

- "International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication – About us". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #212" (PDF). The Carter Center. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #218" (PDF). The Carter Center. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #226" (PDF). The Carter Center. 9 May 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #234" (PDF). The Carter Center. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #240" (PDF). The Carter Center. 13 May 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #248" (PDF). The Carter Center. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-up #254" (PDF). The Carter Center. The Carter Center. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #260" (PDF). The Carter Center. 15 April 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #266" (PDF). The Carter Center. 9 March 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #282" (PDF). The Carter Center. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #286" (PDF). The Carter Center. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #296" (PDF). The Carter Center. 22 March 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- "Guinea Worm Wrapup #302" (PDF). The Carter Center. 29 September 2023.

- Cleveland et al. 2018, "Table 1".

- Eberhard et al. 2014, "Abstract".

- Molyneux & Sankara 2017, Paragraph 7.

- Cleveland et al. 2018, "Experimental infections of hosts with D. insignis".

- Cleveland et al. 2018, "Dracunculus species of squamates".

- Cleveland et al. 2018, "Dracunculus species in chelonians".

- Cleveland et al. 2018, "Natural infections of D. insignis in wildlife".

- Cleveland et al. 2018, ""Dracunculus species in mammals".

Works cited

- Biswas G, Sankara DP, Agua-Agum J, Maiga A (August 2013). "Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease): eradication without a drug or a vaccine". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 368 (1623): 20120146. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0146. PMC 3720044. PMID 23798694.

- Callahan K, Bolton B, Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Withers PC, Meagley K (30 May 2013). "Contributions of the Guinea Worm Disease eradication campaign toward achievement of the Millennium Development Goals". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (5): e2160. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002160. PMC 3667764. PMID 23738022.

- Cleveland CA, Garrett KB, Cozad RA, Williams BM, Murray MH, Yabsley MJ (December 2018). "The wild world of Guinea Worms: A review of the genus Dracunculus in wildlife". Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 7 (3): 289–300. doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.07.002. PMC 6072916. PMID 30094178.

- Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "25. Dracunculus medinensis". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. pp. 285–290. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Eberhard ML, Ruiz-Tiben E, Hopkins DR, Farrell C, Toe F, Weiss A, Withers PC, Jenks MH, Thiele EA, Cotton JA, Hance Z, Holroyd N, Cama VA, Tahir MA, Mounda T (January 2014). "The peculiar epidemiology of dracunculiasis in Chad". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 90 (1): 61–70. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0554. PMC 3886430. PMID 24277785.

- Greenaway C (February 2004). "Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease)". CMAJ. 170 (4): 495–500. PMC 332717. PMID 14970098.

- Grove DI (1990). A History of Human Helminthology (PDF). C.A.B International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2015.

- Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Eberhard ML, Weiss A, Withers PC, Roy SL, Sienko DG (August 2018). "Dracunculiasis Eradication: Are We There Yet?". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 99 (2): 388–395. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-0204. PMC 6090361. PMID 29869608.

- Hotez PJ (2013). "The Filarial Infections: Lymphatic Filariasis (Elephantiasis) and Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm)". Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases: The Neglected Tropical Diseases and Their Impact on Global Health and Development. American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Press.

- Molyneux D, Sankara DP (April 2017). "Guinea worm eradication: Progress and challenges- should we beware of the dog?". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 11 (4): e0005495. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005495. PMC 5398503. PMID 28426663.

- Ruiz-Tiben E, Hopkins DR (2006). "Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication". Adv Parasitol. Advances in Parasitology. 61: 275–309. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(05)61007-X. ISBN 9780120317615. PMID 16735167.

- Spector JM, Gibson TE, eds. (2016). "Dracunculiasis". Atlas of Pediatrics in the Tropics and Resource-Limited Settings (2 ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics. ISBN 978-1-58110-960-3.

- Dracunculiasis Eradication: Global Surveillance Summary, 2021 (Report). World Health Organization. 27 May 2022. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

External links

- "Guinea Worm Disease Eradication Program". Carter Center.

- Nicholas D. Kristof from the New York Times follows a young Sudanese boy with a Guinea Worm parasite infection who is quarantined for treatment as part of the Carter program

- Tropical Medicine Central Resource: "Guinea Worm Infection (Dracunculiasis)"

- World Health Organization on Dracunculiasis