Gulshan-i 'Ishq

The Gulshan-i 'Ishq ("The Rose Garden of Love") is a romantic poem written in 1657 by the Indian Sufi poet Nusrati.[1] Written in the Deccani language, it combines literary and cultural traditions from India and Iran. Manuscripts of the poem, illustrated with lavish paintings, have survived from the 18th century to the present day.

Background

Nusrati was a poet laureate in the court of Ali Adil Shah II, the Sultan of Bijapur.[2] His poem takes inspiration from another Sufi romance, the 16th-century Madhumalati written in the Hindawi language by Sayyid Manjhan Shattari Rajgiri.[3][4] It also resembles Mihr-o-Māh, a Persian poem written in the Mughal court three years before the Gulshan-i ‘Ishq. Deccani poetry at this time was strongly influenced by Persian poetry, but combined it with a distinctively Indian flavour. The use of a garden as a metaphor was well established in Deccani literature, with an unkempt garden representing a world in disarray and a "garden of love" suggesting fulfilment and harmony.[4]

Story

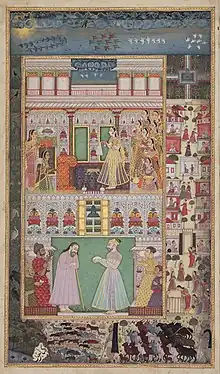

The protagonists of the story are Prince Manohar and Madmalati. Manohar falls in love with Madmalati after seeing her in a dream, and his adventures in search of her take him to fantastical creatures and mythical figures, which are illustrated in the manuscripts' paintings.[2][5] Much of the text describes palaces and natural scenes which Manohar visits.[4] The rose garden serves as a poetic metaphor for spiritual and romantic union.[5] Nusrati uses the poem to complement his patron, listing the virtues of a good ruler and crediting them to Ali Adil Shah II.[4]

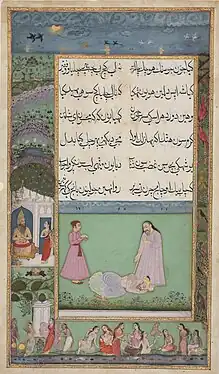

A prelude to the main story describes the journey of Manohar's father, King Bikram of Banakgir, that results in Manohar's birth. Bikram is a perfect ruler who is despondent that his queen has not borne him a child. He offers food to a holy man, Roshan-i Dil, expecting a blessing in return. The holy man refuses the food and leaves without a blessing. Bikram goes in search of him, renouncing his comforts and living a life of extreme poverty as an ascetic with a begging bowl. He eventually encounters Roshan-i Dil again, in a beautiful garden filled with joyous creatures.[4] Having been through a transformative journey and experienced hunger and thirst, he is worthy and is granted a child.[1][4]

Manuscripts

An illustrated manuscript, created at Hyderabad c. 1710, is now dispersed across several collections, including the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1][5] The paintings combine scenes from the narrative with marginal illustrations of rural, urban, and court life.[1]

Another illustrated manuscript dates from AH 1156 (1733–34 AD) and is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It includes 97 colourful paintings and is signed by the calligrapher Ahmad ibn Abdullah Nadkar. The Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad has eight more complete manuscripts.[3]

_MET_TR.179.2011images.jpeg.webp) Fairies descend to the chamber of Prince Manohar, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fairies descend to the chamber of Prince Manohar, Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg.webp) Angels carry Manohar in his bed, San Diego Museum of Art

Angels carry Manohar in his bed, San Diego Museum of Art Bikram prostrates himself before Roshan-i Dil, Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Bikram prostrates himself before Roshan-i Dil, Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Derivative works

In 2016 the Philadelphia Museum of Art commissioned Pakistani-American visual artist Shahzia Sikander to create a ten-minute video work, "Disruption as Rapture", that animates images from its manuscript of the Gulshan-i ‘Ishq.[6][7]

References

- Rogers, J. M. (2008). The arts of Islam : treasures from the Nasser D. Khalili collection (Revised and expanded ed.). Abu Dhabi: Tourism Development & Investment Company (TDIC). p. 289. OCLC 455121277.

- Sharma, Sunil (2020). "Forging a Canon of Dakhni Literature: Translations and Retellings from Persian". In Overton, Keelan (ed.). Iran and the Deccan: Persianate Art, Culture, and Talent in Circulation, 1400–1700. Indiana University Press. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-253-04894-3.

- Parihar, Subhash (2014). "Review of The Visual World of Muslim India: The Art, Culture and Society of the Deccan in the Early Modern Era". Islamic Studies. 53 (1/2): 123. ISSN 0578-8072.

- Husain, Ali Akbar (2011). "Reading Gardens in Deccani Court Poetry: A Reappraisal of Nusratī's Gulshan-i 'Ishq". In Ali, Daud; Flatt, Emma J. (eds.). Garden and landscape practices in precolonial India : histories from the Deccan. New Delhi. pp. 149–154. ISBN 978-1-003-15787-8. OCLC 1229166032.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (2015). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-0-300-21110-8. OCLC 898114277.

- "Disruption as Rapture". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- Earnest, Jarrett; Zwirner, Lucas; Bui, Phong (2017-11-21). "Shahzia Sikander". Tell Me Something Good: Artist interviews from the Brooklyn Rail. Simon and Schuster. pp. 414–416. ISBN 978-1-941701-37-9. OCLC 1014181259.

Further reading

- Leach, Linda York (1998). Paintings from India. London: Nour Foundation. pp. 240–247. ISBN 9780197276297. OCLC 41257043.

- Haidar, Navina Najat (2014). "Gulshan-I 'Ishq: Sufi Romance of the Deccan". In Parodi, Laura E.; Eaton, Richard M. (eds.). The Visual World of Muslim India: The Art, Culture and Society of the Deccan in the Early Modern Era. London: I.B.Tauris. pp. 295–318. ISBN 978-0-7556-0561-3. OCLC 1128174855.