HMS Apollo (1794)

HMS Apollo, the third ship of the Royal Navy to be named for the Greek god Apollo, was a 38-gun Artois-class fifth rate frigate of the Royal Navy. She served during the French Revolutionary Wars, but her career ended after just four years in service when she was wrecked on the Haak sands off the Dutch coast.

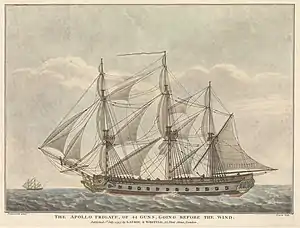

The Apollo frigate going before the wind | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Apollo |

| Ordered | 28 March 1793 |

| Builder | Perry & Hankey, Blackwall |

| Laid down | March 1793 |

| Launched | 18 March 1794 |

| Completed | 23 September 1794 at Woolwich Dockyard |

| Commissioned | August 1794 |

| Fate | Wrecked on 7 January 1799 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | 38-gun Artois-class fifth rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 994 12⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 39 ft 2 in (11.9 m) |

| Depth of hold | 13 ft 9 in (4.19 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 270 |

| Armament |

|

Construction

Apollo was ordered on 28 March 1793 and was laid down that month at the yards of John Perry & Hanket, at Blackwall.[1] She was launched on 18 March 1794 and was completed at Woolwich Dockyard on 23 September 1794.[1][2] She cost £13,577 to build; this rising to a total of £20,779 when the cost of fitting her for service was included.[1]

Career

Apollo was launched in March 1794 and commissioned in August under her first commander, Captain John Manley.[1] Her career began inauspiciously, when Manley accidentally ran her aground on sandbanks in the mouth of the Wash in late 1794. On Manley's orders the ship was lightened by the disposal over the side of her stores and several of her guns, after which she floated free of the sand. Her rudder had broken in the process, and after some difficulty she was sailed to Great Yarmouth for repairs.[3]

In June 1796, she and Doris captured the French corvette Légère, of twenty-two 9-pounder guns and 168 men. Légère had left Brest on 4 June in company with three frigates. During her cruise she had captured six prizes. However, on 23 June she encountered the two British frigates at 48°30′N 8°28′W. After a 10-hour chase the British frigates finally caught up with her; a few shots were exchanged and then Légère struck.[4] The Navy took into her service as HMS Legere.[5]

Then in December, Apollo and Polyphemus were off the Irish coast when they captured the 14-gun French privateer schooner Deux Amis, of 100 tons bm and 80 men.[6] The Royal Navy took her into service under her existing name.

In 1798 Captain Peter Halkett was appointed to the command of Apollo. Apollo shared with Cruizer, Lutine, and the hired armed cutter Rose the proceeds from the capture on 13 May of the Houismon, Welfart, and Ouldst Kendt.[Note 1]

Fate

An accident at sea in late 1798 forced Apollo back to port in Great Yarmouth and left her with a depleted crew. A capstan pawl, or crossbar, had broken while the crew were raising the anchor, and the weight of the anchor and chain caused the remaining pawls to turn sharply as the anchor ran back out. Around thirty men were injured after being struck by the pawls.[8] Halkett gave orders for a prompt return to port, where the injured men were discharged from Apollo's service and entrusted to local medical care. The ship then put back to sea on 5 January, without replacing the injured crew.[8]

Halkett's orders were to take Apollo to a point off the coast of Holland, and there to seek out Dutch vessels for capture. One such vessel was sighted on 6 January, and Apollo was turned to give chase. The pursuit was hampered by thick fog, and at 7am on the following morning Apollo ran aground on the Haak Sandbank adjacent to Texel. Halkett ordered that the ship's stores and guns be thrown overboard in order to lighten her and float her free, but despite these efforts she remained stuck fast in the sands.[8]

In the late afternoon, a Prussian galliot was sighted and hailed by Apollo's crew. After some negotiation, the Prussian captain agreed to jettison the bulk of his cargo of wines and take 250 of Apollo's crew back to England. The remaining crew members went aboard Apollo's cutter with plans to make their own way to port. By 9pm all crew members had left the British ship, which was then abandoned to the tides. The Prussian ship reached Yarmouth on 11 January, followed three days later by the cutter.[8]

A Royal Navy court martial was established to examine the reasons for the loss of the ship. Apollo's pilot, John Bruce was found to have shown "great want of skill" in the execution of his duties, and he was dismissed forthwith from naval service.[9] No findings were made against Captain Halkett, who returned to the Navy at his previous rank and was granted command of a newly completed 36-gun frigate, also named Apollo.[10]

HMS Apollo sank deep into the sea bed. But erosion resurfaced the wreckage. In 2020 the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands commissioned sonar research and divers from the North Sea-Divers from Breezand in North Holland took the guns and equipment out of the water.[11]

Notes

- A seaman's share of the prize money was worth 4s 6d.[7]

Citations

- Winfield. British Warships in the Age of Sail. p. 135.

- Colledge. Ships of the Royal Navy. p. 178.

- Grocott 1997, p. 13

- "No. 13909". The London Gazette. 5 July 1796. p. 644.

- Winfield (2008), p. 255.

- "No. 13970". The London Gazette. 10 January 1797. p. 31.

- "No. 15972". The London Gazette. 4 November 1806. p. 1452.

- Grocott 1997, p67

- Hepper 1994, p. 90

- Winfield (2008), p. 155.

- Nederlandse duikers vinden kanonnen van gezonken Brits oorlogsschip uit 1799

References

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Gardiner, Robert (2006). Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-292-5.

- Grocott, Terence (1997). Shipwrecks of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Eras. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1861760302.

- Hepper, David J. (1994). British Warship Losses in the Age of Sail, 1650–1859. Rotherfield: Jean Boudriot. ISBN 0-948864-30-3.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.