HMS Caroline (1795)

HMS Caroline was a 36-gun fifth-rate Phoebe-class frigate of the Royal Navy. She was designed by Sir John Henslow and launched in 1795 at Rotherhithe by John Randall. Caroline was a lengthened copy of HMS Inconstant with improved speed but more instability. The frigate was commissioned in July 1795 under Captain William Luke to serve in the North Sea Fleet of Admiral Adam Duncan. Caroline spent less than a year in the North Sea before being transferred to the Lisbon Station. Here she was tasked to hunt down or interdict French shipping while protecting British merchant ships, with service taking her from off Lisbon to Cadiz and into the Mediterranean Sea. In 1799 the ship assisted in the tracking of the French fleet of Admiral Étienne Eustache Bruix, and in 1800 she participated in the blockade of Cadiz.

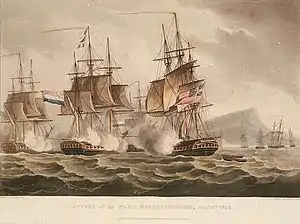

Caroline off Shakespeare Head by Thomas Buttersworth | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Caroline |

| Ordered | 24 May 1794 |

| Cost | £24,560[1] |

| Laid down | June 1794 |

| Launched | 17 June 1795 |

| Completed | 25 September 1795 |

| Commissioned | July 1795 |

| Fate | Broken up September 1815 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Phoebe-class fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 924 44⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 38 ft 3 in (11.7 m) |

| Depth of hold | 13 ft 5+1⁄2 in (4.1 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Complement | 264 |

| Armament |

|

In 1803 Caroline brought the news of the declaration of war with France to the East Indies where she would stay for the rest of her service. The ship's main role in the Indies was attacking the possessions of the French and their allies and as such she participated in a number of important events, including the Java campaign of 1806–1807 in which she fought the action of 18 October 1806. The frigate also played an active role in the Persian Gulf campaign of 1809, the invasion of the Spice Islands where her crew were instrumental in capturing Banda Neira, and the invasion of Java in 1811. After this Caroline returned home to be paid off at Portsmouth where she was hulked. Her last, and most successful, commander was Captain Sir Christopher Cole. Caroline was broken up at Deptford in 1815.

Construction

Caroline was a 36-gun, 18-pounder Phoebe-class frigate designed by Sir John Henslow.[1][2] Her class was designed as a lengthened version of the frigate HMS Inconstant.[2] This was an attempt by the Admiralty at the beginning of the French Revolutionary War to increase the speed and general performance of their frigates.[2] The new ships were given wider gun port spacings than on Inconstant in an attempt to increase spacing between the guns themselves, which resulted in guns having to be placed on the extreme ends of the ships.[3][4] This in turn meant that the class was known to pitch heavily.[3]

The ships were thought to be slightly faster than previous designs of Henslow, being capable of reaching 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph), but bought this speed with decreased stability.[3][5] Similar to other ships designed in the 1790s, Caroline had solid barricades on the quarterdeck and forecastle to increase protection to the crew and provide extra space for guns.[6] The ship had originally been planned to hold 6-pound guns in these new positions, but on 16 March 1795 before the ship had been launched, the 6-pounders were upgraded to 9-pounders and her ten 32-pound carronades were also added to the design.[7]

Caroline was ordered to be built at Rotherhithe by John Randall & Co. on 24 May 1794. She was laid down in June of the same year and launched on 17 June 1795 with the following dimensions: 142 feet 6 inches (43.4 m) along the gun deck, 118 feet 9+1⁄2 inches (36.2 m) at the keel, with a beam of 38 feet 3 inches (11.7 m) and a depth in the hold of 13 feet 5+1⁄2 inches (4.1 m). She measured 924 44⁄94 tons burthen. The fitting out process for Caroline was completed at Deptford on 25 September.[1] The design and armament of the ship were not considerably altered after her launch or during service, with the only major change being the addition of two 6-pounders on 4 March 1805.[8] As such she sailed throughout her career with twenty-six 18-pounders on her gundeck, eight 9-pounders and six 32-pound carronades on her quarterdeck, and two 9-pounders and four 32-pound carronades on her forecastle.[1] Other ships of her class such as HMS Phoebe and HMS Fortunee received armament overhauls in 1812 and 1813, but by this point Caroline had already been hulked.[8]

Service

1795–1797

Caroline was commissioned by Captain William Luke in July 1795 to serve in the French Revolutionary Wars, beginning her career in the North Sea Fleet of Admiral Adam Duncan. The frigate served in close contact with Duncan, being able to react quickly to his orders and split off from the fleet where necessary.[9] On 1 December the frigate took the 14-gun brig Le Pandore off the Texel after a chase of one hour, however Le Pandore's companion, the 12-gun brig Le Septnie, escaped while the crew of Le Pandore were being removed.[10][11][12] After this Caroline transferred to the Lisbon Station, tasked with patrolling from Cape Finisterre to the southern border of Spain and Portugal, where she took an 18-gun corvette in April 1796, and the 10-gun privateer polacre La Zenodene off Cape Palos on 23 May.[1][13][11][14] Soon after this on 11 August the frigate sailed briefly for the Mediterranean Sea.[1] There the frigate captured the French privateer Rochellaire on 20 August alongside the ships-of-the-line HMS Queen and HMS Valiant, the frigate HMS Alcmene, and the sloop HMS Raven.[15] Sailing with the ship-of-the-line HMS St Albans and the frigates Alcmene and HMS Druid, she then captured the Spanish merchant Adriana on 5 November.[16] Activity continued into 1797, with the Spanish brig San Joseph being captured by Caroline and the frigate HMS Seahorse on 16 February and another Spanish brig, San Luis, taken by Caroline on 5 July.[17][18] In September she sailed to the Cape of Good Hope with Colonel Arthur Wellesley on board as he went to join his regiment in India.[19]

1798–1799

The frigate continued throughout this period to serve on the Lisbon Station while also spending considerable time around Cadiz and the edges of the Mediterranean while assigned to Admiral Lord St Vincent's fleet.[20] As part of such, in 1798, she shared in the proceeds of the capture of the merchants Umbarca Souda, on 18 February, Constanza, on 26 April, and Strella de Mare, on 9 May, and the Spanish privateer El Carmen on 27 February.[21][22] Between 19 March and 26 April Caroline also captured the French privateers Le Francois, Le Fortune, and Le Vainqueur.[23] The ship recaptured the East India Company ship Crescent on 29 June, after she had been taken by the French privateer Mercure on 17 June.[24] Caroline continued to share in the fleet's merchant captures, with Il Terrice on 21 July and Virgin d'Idra on 18 September.[21] While patrolling off the Savage Islands with the frigate HMS Flora on 4 October, Caroline took the privateer Le President Parker.[Note 1] Earlier in the day the frigate had retaken the merchant ship Bird of Liverpool, on her way to Africa, which had been taken by Le President Parker on 27 September.[25]

This began a small string of successes for Caroline, with her boats destroying the 1-gun privateer L'Esperance at Tenerife on 16 October and four days later taking the 10-gun privateer Le Baret at the same location, again with Flora.[1][20] The ship also shared in the capture of the merchants Nostra Senora de Misericordia and San Joseph on 20 October.[21] In November command of the ship briefly transferred to Captain Lord Henry Paulet.[27] On 21 November Caroline and Flora took the Spanish merchant El Bolante off Madeira, and then on 23 November the 10-gun French privateer La Garonne.[28] In December Paulet was replaced by Captain William Bowen; Caroline took the 12-gun privateer brig Le Ferailleur on 4 December by tricking her into believing the frigate and two small prizes with her were a merchant convoy.[Note 2][1][30] Caroline continued on station off Lisbon throughout 1799 as well.[31] On 27 January the frigate recaptured the British letter of marque Jane which she had been chasing since Jane's captor, the privateer L'Intrepide, had been taken and disclosed her location on 25 January.[32] In the same month Drie Vrienden Hoy and the brig Nymph were also recaptured.[33] With continuing success, Caroline and Flora retook Six Sisters, which had been captured by a French privateer, in early February and captured the French privateers L'Aventure on 14 February and La Legere on 19 April.[34][35][22] On 24 June the frigate followed and reported the position of Admiral Étienne Eustache Bruix's escaped French fleet to Rear-Admiral Sir Charles Cotton, assisting Cotton in his hunt for Bruix that saw him chase the French from Brest to the Mediterranean.[36] On 31 August Caroline took the privateer La Resolve and then on 26 December El Fleche and La Voiture.[37]

1800–1801

On 15 January 1800 Caroline took the 22-gun privateer Vulture at 37°45′N 13°8′W. Caroline sighted Vulture two hundred miles (320 km) west of Lisbon chasing the merchant brig Flora; Vulture attempted to escape and threw two of her guns overboard to increase her speed, but in the evening Caroline captured her without a shot being fired.[Note 3] The frigate then took the Danish merchant Young Johannes, laden with wine, on 8 April.[39] In late 1800 Caroline began to serve in Rear-Admiral Sir James Saumarez's Cadiz blockade squadron.[40] Caroline often patrolled with the brig HMS Salamine, together taking on Christmas Day the French brig Good Friends, which was laden with cannon and mortars, and the French 4-gun xebec privateer Le Regulus laden with arms on 21 January 1801.[1][41][42][43] Continuing a busy start to the year, Caroline and the brig HMS Mutine detained the Swedish brig Active on 1 February as she travelled to Leghorn.[42] The frigate continued off Cadiz throughout 1801, forming part of the bolstered squadron there in August, retaking the merchantman Prince of Wales on 5 October, and going into Portsmouth from there on 1 December.[Note 4][40][45][46]

1802–1803

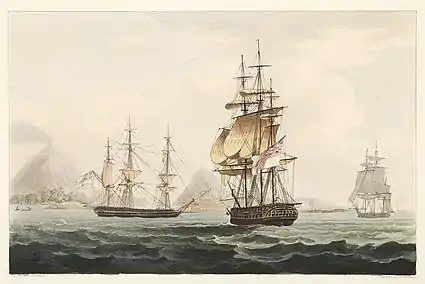

.jpg.webp)

At the start of 1802 Caroline shared in the capture of the merchant Tito with much of the squadron.[47] On 10 February the frigate returned from Cadiz to be paid off at Portsmouth.[48] She was refitted at Woolwich between March 1802 and February 1803, being recommissioned on 9 November 1802, shortly before the Peace of Amiens ended, beginning to serve in the Napoleonic Wars under Captain Benjamin William Page.[1][49] Caroline served on the Irish Station until May 1803.[50] The ship then received immediate orders to sail for the East Indies carrying the declaration of war upon France and instructions to detain all Dutch vessels. Page had so little time to react that the ship was never configured for service anywhere else but Ireland.[Note 5][50][52]

On 28 May Caroline was in sight of the ship-of-the-line HMS Victory as she captured the French frigate L'Ambuscade, previously the British HMS Ambuscade, and thus shared in the prize of her.[53] A day later she captured the French merchant brig La Bonne Mere.[35] Caroline took the 6-gun privateer Haasje off the Cape of Good Hope on 2 August while on voyage; Haasje had been bound for India with dispatches from Napoleon.[1][54][55] Haasje was sent in to Saint Helena, where the news of war she carried caused Dutch ships to be impounded and English merchant ships to stop sailing out of convoys.[54] No longer having to keep her knowledge of the war secret, the ship detained the Dutch merchant Henrica Johanna on 3 August.[Note 6][56] The passage to the East Indies took 103 days, with Caroline only stopping briefly at Madeira for water and wine.[50] Here Caroline sent dignitaries to the governor of the island, only for the representatives to mistake the governor's butler for him.[57] The frigate completed the voyage of 13,000 miles without losing any men to sickness, for which the discipline and cleanliness of the ship were praised.[58] The ship arrived in the East Indies on 6 September and took the French merchant Petite Africaine a day later.[59][60]

1804

For the next few months into early 1804 Caroline escorted convoys through the Bay of Bengal, and then on 5 January captured the 8-gun privateer Les Frères Unis around sixty miles (97 km) south-west of Little Andaman.[Note 7][62][63][50] During the pursuit one crewmember of Les Frères Unis was killed by a musket shot from the frigate; fifty-five members of her crew were actually soldiers who had travelled to Mauritius from Bourdeaux in July 1803. On 4 February Caroline discovered the 26-gun privateer Le Général du Caen in the channel south of Preparis island; both ships used all their possible sail in the ensuing chase but the frigate used her superior sailing qualities to get close enough to fire into Le Général du Caen with her chase guns, at which point she surrendered.[1][62] Les Frères Unis and Le Général du Caen were both taken soon after their arrival from France and did not have any time to attack British shipping before being captured. The service of Caroline in stopping these privateers was rewarded in the presenting of swords worth 500 guineas to Page from both the Bombay and Madras merchant communities.[54]

On 10 March Caroline was sent as lead escort ship, along with the fourth-rate HMS Grampus, frigate HMS Dedaigneuse, and sloop HMS Dasher, to protect the valuable Bengal convoy sailing to and from China.[64][65] It was suspected by Vice-Admiral Peter Rainier that the convoy would come under attack from the French admiral Charles-Alexandre Léon Durand Linois's squadron as had happened previously with Commodore Nathaniel Dance's convoy.[Note 8][64] In early October Caroline and the convoy weathered a typhoon.[68] In the last day of this, a seaman on Caroline fell from her masts; the frigate was not able to halt her progress for another three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km), and the seaman was presumed drowned.[69] When further investigated it was found that the man was still swimming strongly in the distance and six men went in the ship's jolly boat to rescue him. Upon bringing the man back, the occupants of the boat were swept overboard by the waves as it was being brought on board; the boat was cut from its ropes into the sea again, and all survived in what was described as an 'extraordinary instance of preservation'.[70] No attack being made on the convoy, it reached Canton at the end of November and returned safely on 20 January 1805.[64][71]

Java campaign

1805–1806

In April 1805 Captain Peter Rainier assumed command of Caroline.[Note 9][62][73] She captured the French 14-gun privateer brig Gautavie in the same month.[74] Gustave, of 20 guns and 120 men, prize to Caroline arrived at Bombay on 7 April.[75]

Midway through 1805, Caroline's surgeon, the writer and disease expert James Johnson, left the ship; through his travels with the ship he had compiled a series of geographical and medical notes, as well as naval anecdotes, that he used to produce a number of works including The Oriental Voyager.[76]

In October 1806 the frigate was part of Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Troubridge's squadron blockading Batavia, from where a large Dutch squadron had been threatening merchant shipping.[77] On the morning of 18 October Caroline took a small brig while on station.[62] The crew of this brig informed Rainier that the 36-gun Dutch frigate Phoenix was currently under repair nearby, and Caroline set out to find her.[62][78]

While doing so, the ship discovered two brigs at anchor off Batavia; one of these was the 14-gun Dutch brig Zeerob which had sailed from Bantem.[Note 10][1][62] Zeerob was captured by Caroline, but the other brig was too close to the shore to be pursued and made her escape into Batavia, where she sheltered with Phoenix and the 36-gun frigate Maria Reijersbergen, the 20-gun sloop William, the 18-gun Patriot, and the 14-gun Zeeplong.[62][78] As the brig escaped, Phoenix emerged from the inner harbour in an attempt to manoeuvre away from Caroline.[78] Caroline entered the harbour and sailed for Maria Reijersbergen, determining her to be the largest threat, firing at her from the range of half a pistol shot; after around thirty minutes of bombardment the Dutch frigate surrendered.[62][78] Her consorts, Patriot, William, and Zeeplong, all failed to engage Caroline, making the battle much fairer than it should have been considering the number of ships present.[79]

While Maria Reijersbergen had a full complement of 270 men, Caroline was fifty-seven men below complement in the fight due to men having been sent away in prize ships or being in hospital.[62][78] The ship had three seamen killed as well as four Dutch prisoners who were being held in the hold at the time; eighteen men were wounded with six mortally so, including the lieutenant of marines.[1][80] The Dutch ship had around fifty men killed and wounded and was heavily damaged due to the efficiency of Caroline's guns; her rigging (including a yard shot in half), masts, and hull all received damage in the battle.[78][81][79] Caroline fought her opponent in very shallow water surrounded by dangerous shoals, and was not able to chase the other ships that had been sheltering alongside the frigate. Despite this the Dutch ships, including six merchants, ran themselves aground to ensure they would not be captured by her.[62][82]

On 27 November a squadron under Rear-Admiral Edward Pellew sailed for Batavia to complete the destruction begun by Caroline.[Note 11] Pellew's ships could not enter due to the shallow shoals, and thus sent in their boats to attack the beached Dutch vessels; Phoenix's crew scuttled her upon the boats' approach, and the British succeeded in burning all the ships that had escaped Caroline.[79] Maria Reijersbergen was bought into the Royal Navy as HMS Java.[Note 12][62]

1807

On 27 January 1807 the frigate was sailing near the Philippines having recently finished convoying the East India Company ships Perseverance and Albion, when a strange sail was sighted on the horizon.[78] [83] A chase of the ship ensued and when Caroline came within gunshot the ship raised Spanish colours; soon after the enemy ship was discommoded by a change in the winds and the ship was able to come alongside her. The enemy ship, despite being much smaller than Caroline, began to fire into her; the frigate returned her fire, and the ship surrendered to her after having twenty seven of her crew killed or wounded.[78] Upon investigation it was found that the ship was the 16-gun St. Raphael sailing as Pallas, she had on board 500,000 dollars in specie and 1,700 quintals of copper.[Note 13][84] In capturing this valuable prize Caroline had only seven men wounded, of which one later died, but illness meant that she returned to port with only a small portion of her crew fit to serve.[84][83][85]

By June Caroline was with Pellew's squadron, with him serving jointly as commander-in-chief with Troubridge, at Madras.[1] The ship was sent with the frigate HMS Psyche to hunt for two Dutch ships-of-the-line that had escaped from Batavia in 1806, and on 29 August they arrived off Surabaya; here they captured a merchant vessel on 30 August that informed them that the Dutch ships were lying in a state of disrepair inside the nearby port of Gresik.[Note 14][62][87] Having successfully discovered the enemy ships, Psyche went on to destroy a number of Dutch merchant ships lying off the coast while Caroline chased a strange sail.[62] On 31 August Caroline shared by agreement in Psyche's capture of the Dutch corvette Scipio, which was bought into the navy as HMS Samarang.[88] From September Commander Henry Hart took command of the frigate as her acting-captain, still in Pellew's squadron.[89][1][90] On 20 October the squadron left Madras for Gresik, the harbour that Caroline and Psyche had reconnoitered in August.[Note 15][92]

The squadron arrived on 5 December and on 11 December attacked the port. Caroline was used by Pellew as his flagship for some of the operation after his actual flagship, the ship-of-the-line HMS Culloden, grounded herself and her crew became intoxicated on a store of liquor.[93] When Culloden grounded Caroline was directly astern of her and it was thought that Caroline would either hit Culloden or have to run herself ashore to escape that, but through the quick use of a spare anchor the crisis was averted just before Caroline hit the flagship's stern.[94] The squadron then burned the three Dutch ships-of-the-line present, and a large merchant ship, all of which had been scuttled by the Dutch, and destroyed the fort, its gun batteries, and the dockyard.[Note 16][96][95][97] Hart was in charge of the landings and then commanded the troops during the attack against the port's infrastructure.[98]

This action meant that the Dutch no longer had an active navy presence in the East Indies.[99] A committee from Surabaya spoke with the squadron and stopped further destruction in return for their assistance in replenishing the squadron with food and other supplies.[96] Having repaired and replenished themselves, the ships left Gresik on 17 December.[100] Continuing her duties, Caroline participated in an engagement with a series of batteries and gunboats at the entrance of Manila Bay soon after this.[98] Despite having served for four years in the Indies, it was reported around this time that the crew had not become more seasoned to the climate and were still harshly affected by the heat, diseases and other effects present.[51]

Persian Gulf campaign

1808–1809

In the first months of 1808 Caroline captured the merchant ships Le Gustave and Le Paroudi Patche.[101] On 21 December Captain Charles Gordon took over from Hart, and the frigate moved to operate in the Persian Gulf to combat pirates in November 1809.[98][1] The same month, Caroline assisted in destroying over eighty pirate vessels at Ras-al-Khyma.[62][102] This was a well-known pirate stronghold that was set to be attacked along with Lingeh and Laft.[103] Caroline was sailing alongside the frigate HMS Chiffonne and several vessels of the Bombay Marine; the smaller vessels bombarded the coast on 12 November in advance of a landing of troops including Gordon and marines from the frigate on 13 November.[Note 17][62][104] By 10 a.m. the town had been captured by the landing force and before 4 p.m. all the pirate ships had been set on fire and destroyed, as well as all the naval storehouses in the town.[105] The troops re-embarked at midday on 14 November with Caroline having only one man injured.[62] While Chiffonne continued to attack and burn pirate vessels on the coast, Caroline was detached to convoy the transports containing the soldiers that had assisted in the attack.[106] One of the ship's lieutenants later died of an illness contracted while fighting at Ras-al-Khyma.[107]

Invasion of the Spice Islands

1810

In early 1810 Captain Christopher Cole assumed command of Caroline after requesting a transfer from his previous command, the frigate HMS Doris.[62] The frigate briefly served as the flagship of Rear-Admiral William O'Bryen Drury, who was now commander-in-chief, in April from where he organised the capture of Amboyna Island.[108] On 10 May Caroline became the lead ship of a squadron including the frigate HMS Piedmontaise, the brig-sloop HMS Barracouta, and the gun-brig HMS Mandarin.[62] Mandarin was used as a transport to carry 100 soldiers of the Madras Regiment, money, and provisions for the garrison of the recently captured Amboyna.[62][1][109] While travelling to the island the squadron stopped at Penang Island to embark artillerymen, two field guns, and twenty scaling ladders with the intent of assaulting Banda Neira before reaching Amboyna.[62][109] After a passage of over six weeks, the ships entered the Java Sea on 23 July and approached Banda Neira on 8 August; Cole described the voyage as the most difficult he had ever made.[Note 18][1][62][111] Fearing that the Dutch would reinforce the island before they could attack it, the squadron had taken a quicker but more dangerous route than might have been expected.[112] Banda Neira was a heavily guarded island, having been reinforced since its previous capture by the British in 1796 with two major forts and ten other batteries of guns.[113]

It had originally been planned that the squadron's ships would enter the harbour under the cover of darkness, but while attempting such they were fired on by a gun battery on the nearby Rosensgen Island, which the British had not been aware of, and retired.[114][115] Instead the squadron's small boats were put into action, embarking soldiers and seamen in the evening. As the boats began to rendezvous together at 2 a.m. for the attack the weather turned for the worse with rain and thunder and many boats were swept off course, leaving 200 men to make the attack of which only 40 were soldiers.[62][116] With a full-scale attack no longer possible, the boats available to Cole instead aimed to attack two batteries that could hinder the squadron as it attempted to enter the harbour again the following morning.[62] The Dutch expected any landing to occur at the north of the island, where the previous one had, and thus by landing in a different location the boats gained the element of surprise.[117] Landing in the rain, a 10-gun battery was taken quickly from behind with sixty prisoners captured for no casualties.[116][118] Twenty minutes after this the force assaulted one of the two major forts, Fort Belgica, mounting fifty-two cannons; the attack was initially successful when they used their ladders to scale the outer walls.[62][119][120] The rain continued, making it impossible for the defending Dutch force to fire their cannons more than three times, but the attackers found their ladders too short to scale the inner walls of the fort.[62] Instead the force rushed the main gateway which had been opened to allow Dutch officers that lived outside the fort to enter it. The fort's commandant and ten Dutch soldiers were killed in the attack with another four officers and forty men captured.[118]

In the morning the ships entered Banda Neira's harbour with Caroline leading. The remaining batteries fired on the ships, but shots from the captured Fort Belgica and a threat to storm Fort Nassau, the other major fort, brought defence of the island to an end.[Note 19][62][121] 120 guns and 700 Dutch soldiers were captured with no loss to the attacking force.[62][122] Caroline's first lieutenant, John Gilmour, commanded the frigate while Cole was ashore despite suffering from a severe illness, and took the captured colours of the forts to Drury.[Note 20][122] In celebration of the victory, the captains of Piedmontaise and Barracouta had a silver cup made for Cole, while the officers of the squadron and the officers of the Madras Regiment and artillery both presented him with swords worth 100 guineas.[Note 21][62] The capture was thought to be worth £600,000 for the captors, with there being £400,000 worth of spice alone.[125][126] Caroline sailed for Madras on 15 August but Drury was absent attacking Mauritius, and so the ship instead went to Bombay for a refit.[62][127] In September she brought the new governor and staff-officers to Banda Neira.[126]

Invasion of Java

1811

In 1811 Caroline joined Drury's forces off the Malabar Coast to prepare for an attack on Java.[Note 22][1][62] On 6 March the now Vice-Admiral Drury suddenly died, leaving Cole to continue preparations in his stead until Rear-Admiral Robert Stopford and Captain William Robert Broughton arrived later in the year.[62] By the time of the arrival of these senior officers Cole had almost completed the preparations for the invasion.[129] On 4 August the large force under Stopford arrived in Chillingching Bay, east of Batavia. Caroline was the lead frigate alongside HMS Modeste and HMS Bucephalus charged with covering the debarkation of the invasion forces on the beaches.[62] It was found that no enemy forces were contesting the landing and that two batteries meant to be guarding the location were unfinished, so Cole ordered 8,000 men to land immediately from the boats of the frigates, successfully doing so before the Dutch (who had been rushing to reach the site) were able to respond.[130][131] The Dutch having arrived to contest the invasion seven hours after the landing, Cole requested that he take 400 seamen ashore to further assist the soldiers, but his offer was declined and Caroline played no further action in the invasion.[132][131] Between 4 and 28 August at Java Caroline had two men killed, three wounded, and one missing.[133]

Cole was personally thanked for his actions by the Governor-General of India Lord Minto and the commander-in-chief of the forces Major-General Sir Samuel Auchmuty.[129] The invasion was a success, and Caroline was chosen to take Stopford's dispatches on the action back to Britain, arriving there on 15 December.[62][130][131] The voyage took the ship ninety-four days, which was thought to be the second fastest passage from the East Indies to date.[Note 23][134] Cole was knighted on 29 May 1812 for his service, and the crew of Caroline presented him with a sword worth 100 guineas and an epistle thanking him for his kindess and bravery while in command of them.[62][135]

Fate

Her service over, Caroline was paid off at Portsmouth in January 1812.[1][135] In November 1813 she was fitted as a salvage ship to weight the wreck of the 100-gun ship-of-the-line HMS Queen Charlotte which had blown up in an accident off Capraia in 1800.[1] The ship was broken up at Deptford in September 1815.[1][136]

Prizes

| Vessels captured or destroyed for which Caroline's crew received full or partial credit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Fate | Ref. |

| 1 December 1795 | Le Pandore | 14-gun brig | Captured | [10] | |

| April 1796 | Not recorded | 18-gun corvette | Captured | [1] | |

| 23 May 1796 | La Zenodene | 10-gun privateer polacre | Captured | [1] | |

| 20 August 1796 | Rochellaire | Privateer | Captured | [15] | |

| 5 November 1796 | Adriana | Merchant vessel | Captured | [16] | |

| 16 February 1797 | San Joseph | Merchant brig | Captured | [17] | |

| 5 July 1797 | San Luis | Merchant brig | Captured | [18] | |

| 18 February 1798 | Umbarca Souda | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 27 February 1798 | El Carmen | Privateer | Captured | [22] | |

| 26 April 1798 | Constanza | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 19 March - 26 April 1798 | Le Francois | Privateer | Captured | [23] | |

| 19 March - 26 April 1798 | Le Fortune | Privateer | Captured | [23] | |

| 19 March - 26 April 1798 | Le Vainqueur | Privateer | Captured | [23] | |

| 9 May 1798 | Strella de Mare | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 29 June 1798 | Crescent | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [24] | |

| 21 July 1798 | Il Terrice | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 18 September 1798 | Virgin d'Idra | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 4 October 1798 | Bird | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [137] | |

| 4 October 1798 | Le President Parker | 12-gun privateer | Captured | [1] | |

| 16 October 1798 | L'Esperance | 1-gun privateer | Destroyed | [1] | |

| 20 October 1798 | Le Baret | 10-gun privateer | Captured | [20] | |

| 20 October 1798 | Nostra Senora de Misericordia | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 20 October 1798 | San Joseph | Merchant vessel | Captured | [21] | |

| 21 November 1798 | El Bolante | Merchant vessel | Captured | [28] | |

| 23 November 1798 | La Garonne | 10-gun privateer | Captured | [28] | |

| 4 December 1798 | Le Ferailleur | 12-gun privateer brig | Captured | [1] | |

| 25 January 1799 | L'Intrepide | Privateer | Captured | [32] | |

| 27 January 1799 | Jane | Letter of marque | Recaptured | [32] | |

| January 1799 | Drie Vrienden Hoy | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [33] | |

| January 1799 | Nymph | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [33] | |

| 14 February 1799 | L'Aventure | Privateer | Captured | [35] | |

| February 1799 | Six Sisters | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [34] | |

| 19 April 1799 | La Legere | Privateer | Captured | [22] | |

| 31 August 1799 | La Resolve | Privateer | Captured | [37] | |

| 26 December 1799 | El Fleche | Privateer | Captured | [37] | |

| 26 December 1799 | La Voiture | Privateer | Captured | [37] | |

| 15 January 1800 | La Ventour | 22-gun privateer | Captured | [1] | |

| 8 April 1800 | Young Johannes | Merchant vessel | Captured | [39] | |

| 25 December 1800 | Good Friends | Merchant brig | Captured | [41] | |

| 21 January 1801 | Le Regulus | 4-gun privateer xebec | Captured | [43] | |

| 1 February 1801 | Active | Merchant brig | Detained | [42] | |

| 5 October 1801 | Prince of Wales | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [46] | |

| January–February 1802 | Tito | Merchant vessel | Captured | [47] | |

| 28 May 1803 | L'Ambuscade | 32-gun frigate | Captured | [53] | |

| 29 May 1803 | La Bonne Mere | Merchant brig | Captured | [35] | |

| 2 August 1803 | Haasje | 6-gun privateer | Captured | [1] | |

| 3 August 1803 | Henrica Johanna | Merchant vessel | Detained | [56] | |

| 7 September 1803 | Petite Africaine | Merchant vessel | Captured | [60] | |

| 5 January 1804 | Les Frères Unis | 8-gun privateer | Captured | [54] | |

| 4 February 1804 | Le Général du Caen | 26-gun privateer | Captured | [1] | |

| April 1805 | Gautavie | 14-gun privateer brig | Captured | [74] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant brig | Captured | [62] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Zeerob | 14-gun brig | Captured | [1] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Maria Reijersbergen | 36-gun frigate | Captured | [62] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Phoenix | 36-gun frigate | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | William | 20-gun gun-sloop | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Patriot | 18-gun sloop | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Zeeplong | 14-gun brig | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant vessel | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant vessel | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant vessel | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant vessel | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant vessel | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 18 October 1806 | Not recorded | Merchant vessel | Destroyed | [79] | |

| 27 January 1807 | St Raphael | 16-gun treasure ship | Captured | [78] | |

| 31 August 1807 | Scipio | 18-gun corvette | Captured | [88] | |

| 11 December 1807 | Revolutie | 68-gun ship-of-the-line | Destroyed | [95] | |

| 11 December 1807 | Pluto | 68-gun ship-of-the-line | Destroyed | [95] | |

| 11 December 1807 | Kortenaar | 68-gun sheer hulk | Destroyed | [95] | |

| 11 December 1807 | Ruttkoff | 40-gun merchant vessel | Destroyed | [95] | |

Notes and citations

Notes

- President Parker was a French cutter, of Lorient, under the command of Citizen Ferry. She belonged to the French Republic, which had lent her out to sail as a privateer under a six-month letter of marque. Before she was captured, she had thrown all her guns, shot, and some provisions overboard to lighten her. She had been armed with one 9-pounder gun, and eight 36-pounder carronades.[25] (The carronades were probably obusiers de vaisseau.) President Parker was the Alguille-class Cutter (boat) Poisson Volant, launched in 1794 at Boulogne and lent out for privateering in September 1797.[26]

- Ferailleur possibly Serailleur.[29]

- Vulture, of Nantes, had been out 38 days when captured. She had a crew of 138 men under the command of Citizen Bazill Aug. Ené Laray. she was armed with four 12-pounder and sixteen 6-pounder guns, and two 36-pounder obusiers de vaisseau.[38]

- Prince of Wales possibly Princess of Wales.[44]

- Reinforcements were urgently needed in the East Indies; in July 1803 there were only nine naval vessels on station in total.[51]

- Henrica Johanna was a rich capture, but as a detained ship the crew of Caroline did not receive the full value as they would for a capture; instead they received a part of the value, which was still £30,000.[56]

- Les Frères Unis was pierced for 16 guns but only had 8 on board at her capture. Capture may have taken place on 6 January.[61]

- See Battle of Pulo Aura. The admiral complained to his superiors afterwards that part of the reason that the first convoy attack had occurred was because Caroline had been cruising for prizes instead of following his orders to protect trade.[66][67]

- The commanding officer of Caroline, Captain Peter Rainier, is not to be confused with the admiral serving in the same area, Vice-Admiral Peter Rainier, his uncle.[72]

- Zeerob may also have been of sixteen guns.[62]

- See Raid on Batavia (1806).

- HMS Java served in the Royal Navy for less than a year before being lost with all hands at sea.[79]

- The prize money from the capture was around £170,000 with Rainier alone receiving around £50,000.[80]

- These Dutch ships were the 68-gun ships Pluto and Revolutie.[86]

- The squadron consisted of the ships-of-the-line HMS Culloden and HMS Powerful, the frigates Caroline and HMS Fox, the sloops HMS Victor (or Victoire), HMS Samarang, HMS Seaflower, and HMS Jaseur, and the transport Worcester.[91]

- The ships destroyed were the aforementioned Revolutie and Pluto, as well as the 68-gun sheer hulk Kortenaar, and the 40-gun merchant ship Ruttkoff.[95]

- Bombay Marine ships were HCS Mornington, HCS Aurora, HCS Nautilus, HCS Prince of Wales, HCS Fury, and HCS Ariel.[104]

- While making the journey, the squadron came across a wrecked ship surrounded by pirate vessels which fled upon sight of Caroline. The ship was found to be awash with fresh blood with human hair distributed about, and while nothing could be done for the ship's crew it was noted that a great battle had taken place on the ship.[110]

- This was fortunate, because due to the amount of men away in landing parties Caroline did not have the manpower to both fire her guns and make sail.[121]

- Lieutenant Gilmour was promoted to commander for his services at Banda Neira.[123]

- In later years Cole used the fame he gained in the capture of Banda Neira to bolster his campaign to become Member of Parliament for Glamorganshire.[124]

- Caroline was part of the second division of the expedition, comprising as well as herself HCS Ariel, East India Company ships Hugh Inglis and Huddart, and ten transports.[128] See Transport vessels for the British invasion of Java (1811).

- Caroline was only beaten by Captain John Gore in the frigate HMS Medusa, who had completed the same voyage in eighty four days.[134]

Citations

- Winfield (2008), pp. 352–353.

- Winfield (2008), p. 354.

- Gardiner (1994), p. 31.

- Gardiner (1994), p. 75.

- Gardiner (1994), p. 86.

- Gardiner (1994), p. 77.

- Gardiner (1994), p. 33.

- Gardiner (1994), p. 102.

- "No. 13843". The London Gazette. 10 December 1795. p. 1407.

- "No. 13843". The London Gazette. 10 December 1795. p. 1408.

- Schomberg (1802), p. 75.

- Duncan (1805), p. 380.

- Hall (1993), p. 403.

- Schomberg (1802), p. 143.

- "No. 15038". The London Gazette. 3 July 1798. p. 624.

- "No. 15062". The London Gazette. 18 September 1798. p. 894.

- "No. 14050". The London Gazette. 30 September 1797. p. 951.

- "No. 15434". The London Gazette. 8 December 1801. p. 1466.

- Springer (1966), p. 22.

- Schomberg (1802), p. 146.

- "No. 15321". The London Gazette. 20 December 1800. p. 1430.

- "No. 15464". The London Gazette. 23 March 1802. p. 91309.

- "No. 15229". The London Gazette. 8 February 1800. p. 129.

- "No. 15149". The London Gazette. 17 June 1799. p. 617.

- "No. 15086". The London Gazette. 4 December 1798. p. 1166.

- Roche (2005), p. 355.

- Clarke & McArthur (1800), p. 544.

- Clarke & McArthur (1799a), p. 337.

- Schomberg (1802), p. 148.

- Clarke & McArthur (1799a), p. 434.

- Clarke & McArthur (1799a), p. 570.

- Clarke & McArthur (1799b), p. 626.

- "No. 15369". The London Gazette. 26 May 1801. p. 598.

- Clarke & McArthur (1799a), p. 264.

- "No. 15734". The London Gazette. 4 September 1804. p. 1111.

- Krajeski (1998), p. 75.

- "No. 15448". The London Gazette. 26 January 1802. p. 91.

- "No. 15242". The London Gazette. 25 March 1800. p. 297.

- "No. 15278". The London Gazette. 22 July 1800. p. 843.

- Clarke & McArthur (1801), p. 253.

- Schomberg (1802), p. 164.

- Clarke & McArthur (1801), p. 413.

- "No. 15566". The London Gazette. 12 March 1803. p. 269.

- "No. 15783". The London Gazette. 23 February 1805. p. 265.

- Clarke & McArthur (1801), p. 514.

- "No. 15779". The London Gazette. 9 February 1805. p. 201.

- "No. 15515". The London Gazette. 14 September 1802. p. 993.

- Clarke & McArthur (1802), p. 179.

- O'Byrne (1849b), p. 849.

- Ralfe (1828), p. 258.

- Davey (2017), p. 207.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807b), p. 142.

- "No. 15857". The London Gazette. 2 November 1805. p. 1359.

- Marshall (1823), p. 768.

- Clarke & McArthur (1805b), p. 346.

- "No. 15791". The London Gazette. 23 March 1805. p. 380.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807b), pp. 142–143.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807b), p. 143.

- Brenton (1837), p. 5.

- Clarke & McArthur (1804), p. 70.

- Clarke & McArthur (1805a), p. 220.

- Michael Phillips, Caroline (36) (1795). Michael Phillips' Ships of the Old Navy. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Marshall (1823), p. 769.

- Ralfe (1828), p. 259.

- Clarke & McArthur (1804), p. 239.

- Ward (2013), p. 119.

- Gillespie (1935), p. 168.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807b), p. 412.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807a), p. 305.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807a), p. 306.

- Clarke & McArthur (1807b), p. 415.

- Wareham (1999), p. 119.

- Ward (2013), p. 56.

- Clarke & McArthur (1805b), p. 349.

- "The Marine List". Lloyd's List. No. 4260. 8 October 1805. hdl:2027/hvd.32044105232953. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- Greenhill (1892), pp. 16–17.

- Wareham (1999), p. 188.

- Marshall (1825b), p. 978.

- James (1859a), p. 180.

- Henderson (1970), p. 95.

- Wareham (1999), p. 189.

- Clarke & McArthur (1808a), p. 342.

- Clarke & McArthur (1808a), p. 78.

- Marshall (1825b), p. 979.

- Wilcox (2011), p. 47.

- Henderson (1970), p. 96.

- Marshall (1827b), p. 403.

- "No. 16484". The London Gazette. 11 May 1811. p. 877.

- Cripps (2002), p. S 24.

- Marshall (1828), p. 414.

- James (1859a), p. 283.

- Wilson (1845), p. 354.

- Noel-Smith & Campbell (2016), p. 120.

- Allen (1852), p. 215.

- Clarke & McArthur (1808b), p. 69.

- Wilson (1845), p. 353.

- Allen (1852), pp. 214–215.

- O'Byrne (1849a), p. 471.

- Clarke & McArthur (1808b), p. 145.

- Osler (1835), p. 249.

- "No. 16149". The London Gazette. 28 May 1808. p. 760.

- Marshall (1827a), p. 283.

- Clowes (1897), p. 446.

- Clarke & McArthur (1810), p. 73.

- Marshall (1829), p. 88.

- Marshall (1829), p. 89.

- Clarke & McArthur (1810), p. 264.

- Clarke & McArthur (1810), p. 336.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 505.

- James (1859b), p. 196.

- Davey (2017), p. 220.

- James (1859b), p. 195.

- Intelligence Branch, Army Headquarters India (1911), p. 360.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 506.

- James (1859b), p. 197.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 507.

- James (1859b), p. 198.

- Wilson (1845), p. 347.

- Clowes (1897), p. 293.

- Osler (1835), p. 408.

- James (1859b), p. 201.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 510.

- Clarke & McArthur (1811b), p. 176.

- Robson (2014), p. 199.

- Clarke & McArthur (1811a), p. 153.

- Clarke & McArthur (1811a), p. 196.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 513.

- Clarke & McArthur (1812), p. 109.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 514.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 515.

- Osler (1835), p. 410.

- Ralfe (1828), p. 359.

- Clarke & McArthur (1811b), p. 503.

- Clarke & McArthur (1812), p. 192.

- Marshall (1825a), p. 516.

- Colledge & Warlow (2010), p. 69.

- Clarke & McArthur (1799a), p. 75.

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Brenton, Edward Pelham (1837). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol. 2. London: Henry Colburn.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1799a). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731532.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1799b). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731549.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1800). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731556.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1801). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 6. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731587.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1802). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731594.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1804). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731648.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1805a). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 13. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731679.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1805b). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 14. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731686.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1807a). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731716.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1807b). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731723.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1808a). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731730.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1808b). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 20. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731747.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1810). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731785.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1811a). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 25. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731792.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1811b). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731808.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John (1812). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 27. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511731815.

- Clowes, William Laird (1897). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 5. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2010). Ships of the Royal Navy. Newbury: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-07-1.

- Cripps, Derek (2002). Royal Navy Ships Captains Stations. Vol. 2. London: Arlington House Productions.

- Davey, James (2017). In Nelson's Wake: How the Royal Navy Ruled the Waves after Trafalgar. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22883-0.

- Duncan, Archibald (1805). The British Trident; or, Register of Naval Actions; including Authentic Accounts of all the most Remarkable Engagements at Sea, in which The British Flag has been Eminently Distinguished; from the period of the memorable Defeat of the Spanish Armada, to the Present Time. Vol. 3. London: James Cundee.

- Gardiner, Robert (1994). The Heavy Frigate: Eighteen-Pounder Frigates. Vol. 1. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-627-2.

- Gillespie, R. St J. (1935). "Sir Nathaniel Dance's Battle off Pulo Auro". The Mariner's Mirror. 21 (2): 163–186. doi:10.1080/00253359.1935.10658713.

- Hall, Christopher D. (1993). "The Royal Navy and the Peninsular War". The Mariner's Mirror. 79 (4): 403–18. doi:10.1080/00253359.1993.10656471.

- Henderson, James (1970). The Frigates. London: A & C Black. ISBN 1-85326-693-0.

- Intelligence Branch, Army Headquarters India (1911). Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India. Vol. 6. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India.

- James, William (1859a). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511719721.

- James, William (1859b). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511695056.

- Greenhill, William Alexander (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Krajeski, Paul Christopher (1998). Flags around the Peninsula: The Naval Career of Admiral Sir Charles Cotton, 1753-1812 (PhD). The Florida State University. ISBN 978-0-591-82008-9.

- Marshall, John (1825a). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 2, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 505–517.

- Marshall, John (1827a). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 283–285.

- Marshall, John (1828). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 413–414.

- Marshall, John (1829). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 3. London: Longman and company. pp. 86–93.

- Marshall, John (1823). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 768–769.

- Marshall, John (1827b). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 402–406.

- Marshall, John (1825b). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 2, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 978–979.

- Noel-Smith, Heather; Campbell, Lorna M. (2016). Hornblower's Historical Shipmates: The Young Gentlemen of Pellew's Indefatigable. Woodbridge, England: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-099-6.

- O'Byrne, William R. (1849a). . A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. p. 471.

- O'Byrne, William R. (1849b). . A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. pp. 848–849.

- Osler, Edward (1835). The Life of Admiral Viscount Exmouth. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- Ralfe, James (1828). The Naval Biography of Great Britain: Consisting of Historical Memoirs of Those Officers of the British Navy who Distinguished Themselves During the Reign of His Majesty George III. Vol. 4. London: Whitmore & Fenn. OCLC 561188819.

- Robson, Martin (2014). A History of the Royal Navy: The Napoleonic Wars. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-544-0.

- Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours. Vol. 1. Group Retozel-Maury Millau. ISBN 978-2-9525917-0-6. OCLC 165892922.

- Schomberg, Isaac (1802). Naval Chronology, Or an Historical Summary of Naval and Maritime Events from the Time of the Romans, to the Treaty of Peace 1802: With an Appendix, Volume 5. London: T. Egerton.

- Springer, William Henry (1966). The Military Apprenticeship of Arthur Wellesley in India, 1797–1805 (PhD). Yale University. ISBN 9798659358689.

- Ward, Peter (2013). British Naval Power in the East, 1794–1805: The Command of Admiral Peter Rainier. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-848-7.

- Wareham, Thomas Nigel Ralph (1999). The Frigate Captains of the Royal Navy, 1793–1815 (PhD). University of Exeter.

- Wilcox, Martin (2011). "'This Great Complex Concern': Victualling the Royal Navy on the East Indies Station, 1780–1815". The Mariner's Mirror. 97 (2): 32–48. doi:10.1080/00253359.2011.10708933. S2CID 162218011.

- Wilson, Horace Hayman (1845). The History of British India. Vol. 1. London: J. Madden & Company.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

External links

Media related to HMS Caroline (ship, 1795) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to HMS Caroline (ship, 1795) at Wikimedia Commons- Ships of the Old Navy