HMS Gloucester (1654)

The frigate Gloucester (spelt Glocester by contemporary sources) was a Speaker-class third rate, commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Gloucester after the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660. The ship was ordered in December 1652, built at Limehouse in East London, and launched in 1654. The warship was conveying James Stuart, Duke of York (the future King James II of England) to Scotland, when on 6 May 1682 she struck a sandbank off the Norfolk coast, and quickly sank. The Duke was among those saved, but as many as 250 people drowned, including members of the royal party; it is thought that James's intransigence delayed the evacuation of the passengers and crew.

Johan Danckerts (c. 1682), The Wreck of the Gloucester off Yarmouth, 6 May 1682, Royal Museums Greenwich | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Gloucester |

| Ordered | December 1652 |

| Builder | Matthew Graves, Limehouse |

| Cost | £5,473 |

| Launched | probably March 1654 |

| Commissioned | Margate |

| Owner | Royal Navy |

| Acquired | 1660 |

| Renamed | Gloucester |

| Fate | Wrecked, 6 May 1682 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Speaker-class (third rate) |

| Tons burthen | 75511⁄94 (bm) |

| Length | 117 ft (35.7 m) (keel) |

| Beam | 34 ft 10 in (10.6 m) |

| Depth of hold | 14 ft 6 in (4.4 m) |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 50 guns (as built); 60 guns (1677) |

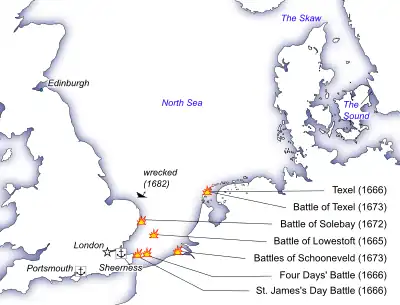

The Gloucester participated in the British invasion of Jamaica (1655), and in the Battle of Lowestoft (3 June 1665). During 1666 she formed part of the fleet that attacked a Dutch convoy off Texel. She fought in the Four Days' Battle (1–4 June 1666) and also took part in the St. James's Day Battle (5 July 1666), the attack on the Smyrna fleet (March 1672), the Battle of Solebay (28 May 1672), and the Battles of Schooneveld (7 June and 14 June 1673). At the end of 1673, having participated in the Battle of Texel (11 August 1673), she was sent to the Mediterranean. Gloucester underwent a comprehensive refit at Portsmouth in 1678, when she was largely rebuilt, at great expense.

In 2007, after a four-year-long search, the wreck of Gloucester was found by an underwater diving team, who have since retrieved a variety of artefacts, including navigational aids, clothing, footwear, and other personal possessions. The wreck has been claimed by Claire Jowitt of the University of East Anglia to be "the single most significant historic maritime discovery since the raising of the Mary Rose in 1982".[1] In 2023, an exhibition relating to the wreck was held at the Castle Museum in Norwich.

Background

Following the end of the English Civil War in 1649, the new Parliamentary regime was threatened by foreign powers and Royalist supporters exiled from England, who targeted maritime trade.[2] To counteract these threats, the government began building up the strength of the navy.[3] It pressed ahead with restoring naval discipline and morale, and reorganising administration to meet wartime needs.[4] It was placing orders for new ships as early as March 1649—by the close of 1651 the English navy had almost doubled in size since the end of the war, with 20 new warships built, and 25 ships acquired by being purchased or captured.[5]

The Commonwealth navy supported the regime in several ways. It assisted in defeating Royalists who threatened English maritime trade, reducing the threat from Royalist-sponsored privateers to commerce, and deterring them by the increased power and size of the fleet. It played a central role in the recapture of the Isles of Scilly, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man, where important royalist privateering bases existed.[6] It played an increasingly important part in consolidating the authority of the new regime in territories previously subject to Charles I. It provided protection for supplies transported by sea during the 1650 invasion of Scotland, and a squadron bombarded Leith (near Edinburgh) to cover the army's advance during the invasion. English naval power did much to persuade European governments of the need to recognize the Commonwealth,[6] and had by 1653 become a major force in shaping international relations.[7]

Development of the line of battle

During the 1650s, the fleets of the European powers generally fought in a melee style that involved fighting between individual ships, but it became clear to the English that the tactic of firing guns from the broadsides of many ships was more effective, and the government worked to convert the fleet to fight in this way.[9] A large ship was vulnerable to raking fire, a volley of cannonballs directly in front or behind it, which could cause considerable damage, and the best protection—and the best form of attack—was having ships sailing together closely and in a straight line.[10] This tactic, known as a line of battle, was used by warships such as the Gloucester, which were large and powerful enough to take their place in the line. Such ships had multiple gun batteries on at least two decks.[3][11] Around 100 ships could be formed into a line of battle.[9]

The Dutch had mobilised quickly at the beginning of the First Dutch War of 1652 and had double the number of ships possessed by the English, but they were smaller and were unsuitable for attacking the English line of battle. Early in the war the English government, recognising the usefulness of large ships, had ordered 30 frigates, to be built at the end of 1652. An early example of a large frigate, the Speaker, launched in April 1650,[3] provided the prototype for a class of ships. The Speaker-class,[2] launched between 1650 and 1654, were about 750 tons and carried between 48 and 56 cannon. Their introduction caused the Dutch Navy, which was still reliant on the use of armed merchant ships, to become largely obsolete.[12] Speaker-class ships had much in common with the old Great Ships planned in 1618, being of a similar size, with two decks and a large number of guns.[3] The class set the pattern for all the two-deck ships built up to the 19th century.[9]

Construction and commissioning

Gloucester (the name of the ship was spelt Glocester by contemporary sources)[13] was a Speaker-class third rate, and the first British naval vessel ship to be named after the English city of Gloucester.[14] She was ordered by the Commonwealth in December 1652 as part of the unprecedented expansion of the English navy during this period, during which 207 battle ships, including 11 frigates, were built.[15][16][17][note 1] The ship was probably launched in March 1654.[16]

Series-built third rates were usually built in commercial shipyards, where costs and construction time were reduced where possible. This was in contrast to the construction of all first rates and second rates, which were built in the Royal Dockyards, where quality control was maintained.[19] The Gloucester cost the navy £5,473, and was built at Limehouse in East London under the direction of master shipwright Matthew Graves.[20] She had a length at the gun deck of 117 feet (35.7 m), a beam of 34 feet 10 inches (10.6 m), and a depth of hold of 13 feet 6 inches (4.1 m). The ship's tonnage was 755 11⁄94 tons burthen. Originally built for 50 guns,[15] by 1667 she was carrying 57 guns (19 demi-cannon, four culverins, and 34 demi-culverins). The ship had a crew of 210–340 officers and ratings.[20]

Service

West Indies (1654–1655)

Gloucester was commissioned in 1654, with Benjamin Blake as captain.[16] Under Blake, Gloucester was with Penn's fleet, an expedition that left England for the Caribbean on Christmas Day 1654. Known as the Western Design, the expedition—consisting of 17 men-of-war, 20 transports with 3000 troops and horses, and other small craft—was intended by Cromwell to end Spanish dominance in the West Indies.[21][22] The expedition was split into two divisions: the first was led to Robert Blake (Benjamin Blakes's older brother) in his flagship HMS St. George; the second, was under Penn on HMS Swiftsure. Another Robert Blake in the expedition was the nephew of Benjamin Blake, who sailed with his uncle on the Gloucester.[23]

Little was achieved. On 14 April 1655, English troops landed in Hispaniola and marched inland. After three days they retreated, exhausted by disease and a lack of supplies. A second attack failed, and eventually the troops had to be re-embarked. Penn then moved on to Jamaica and invaded the island, which surrendered on 17 May.[21][22]

Penn was succeeded by William Goodsonn. His authority was challenged by Blake, his vice-admiral, who wanted to search for prizes, and attack the Caribbean Spanish settlements. Blake, who returned home to England after Goodsonn forced him to resign,[24][note 2] was succeeded as captain of the Gloucester by Richard Newberry.[16] In August 1655 the squadron returned to England, but the Gloucester and 14 other vessels remained out on Jamaica Station.[21]

Operations in The Sound (1658)

In November 1658, after a Dutch fleet commanded by Jacob van Wassenaer Obdam defeated the Swedes in the Battle of the Sound, and lifted the blockade of Copenhagen,[25] the Commonwealth Protector Richard Cromwell ordered a fleet to be sent to the Sound to protect English interests. Gloucester, captained by William Whitehorne, and with 260 men and 60 guns, was one of 20 ships sent to conduct operations in the Sound, under the command of Goodsonn.[26][16][note 3] The English government sent an expedition as a political gesture to dissuade the Dutch from sending a second fleet to the Baltic.[25]

The expedition left the Thames on 18 November 1658. Goodsonn's flagship Swiftsure attempted to join the fleet, but was forced back to port by strong winds. On 3 December the fleet left England for the Skaw, which many were prevented from rounding when they encountered continuous winds.[28] On 15 December, having accomplished little, Goodsonn decided to return home. That night, a gale damaged nearly every ship, including Goodsonn's flagship. None was lost, and from 22 December until the end of the year, they anchored on the English coast between Great Yarmouth and Harwich.[28]

Anglo-Dutch Wars

Battle of Lowestoft (1660)

Renamed in 1660 as HMS Gloucester, the ship participated in the Battle of Lowestoft, forming part of the Red squadron (Van division).[16] The Battle of Lowestoft took place on 3 June 1665,[29] east of the Outer Gabbard and 40 miles (64 km) southeast of the English port of Lowestoft.[29][30] The English under James Stuart, Duke of York, fought a Dutch fleet led by Obdam, in what was the first fleet action of the Second Anglo-Dutch War,[29] The Dutch had 107 ships, of which 81 were warships and 11 substantial East Indiaman. The English fleet of 100 ships, which included 64 men-of-war and 24 merchant ships, was greatly superior in firepower.[30]

At one point during the battle, the firing became heavy enough to be heard in the Hague.[30] The principal event was the sudden explosion of the Dutch flagship Eendracht, which killed Obdam.[29] The Dutch fleet disintegrated and attempted to escape in different directions.[30] By the end of the battle, the English had captured or sunk 17 Dutch ships;[31] a number that would have been larger had not the ensuing pursuit been prematurely called off.[30]

Engagements from May to July 1666

On 5 May 1666, Gloucester, now captained by Robert Clark,[note 4] saw action against the Dutch off the island of Texel,[16] having been stationed there in April with a small squadron to observe the Dutch fleet. A day after his arrival, Clark intercepted a Dutch flotilla of twelve ships en route from the Baltic to Amsterdam, and captured seven of the ships.[21][33] The approach of the enemy's fleet obliged him to leave his station a few days later.[21][33]

Having met with the Duke of Albemarle at the Gunfleet on 24 May, Gloucester participated in the Four Days' Battle (1–4 June 1666). The battle was the longest in British naval history, and has been called the greatest battle of the Age of Sail.[34][35] Gloucester formed part of the White squadron, Centre division. Clark “bore as distinguished a part in the action... as the size of the ship he commanded would allow”.[33] The English lost an opportunity to defeat the Dutch after the king decided to divide the fleet, sending Prince Rupert away down the English Channel with 20 ships towards Ireland, a decision that was reversed once the size of the Dutch threat became clearer.[34][36] Once the English fleet had manoeuvred east of the Kentish Knock on 1 June, so as to reach the Dutch fleet,[35] battle commenced off North Foreland.[34] On 2 June, the English attacked the Dutch, but the Duke of Albemarle was forced onto the defensive. The situation was saved the following day when Prince Rupert's ships reappeared.[34] On the last day, squadrons on both sides broke through enemy lines amid heavy fighting, but eventually the battered English fleet was forced to admit defeat and retreat.[34][37] The English lost 10 ships, most notably the Prince Royal.[35] Gloucester was totally disabled in the action, with 18 men from the ship killed and 27 men wounded. He was soon afterwards promoted to the command of the second rate HMS Triumph.[16][33]

Gloucester and the other English ships were quickly repaired.[38] In early July 1666, the Dutch appeared at the end of the Thames and settled there intending to start a blockade—on 22 July the English sailed out, and the two fleets met three days later.[39] Under her captain Richard May, Gloucester formed part of Blue squadron (Centre division).[16] The St James's Day Battle took place over 25 and 26 July. The weaker and disorganised Dutch fleet, whose line of ships was deliberately made into a snake-like pattern, was heavily defeated.[40]

Attack on the Smyrna fleet (1672)

Under John Holmes, Gloucester participated in the attack on the Smyrna fleet in the North Sea in March 1672.[16] The ship was part a fleet of 20 ships lying off the Isle of Wight, and commanded by his brother Sir Robert Holmes. On 12 March the English sighted the Dutch Smyrna convoy, which consisted of six men-of-war and 66 merchantmen, 24 of which were fully armed. During the fight, five merchantmen were captured, and Gloucester disabled and captured the Klein Hollandia, which later foundered off Eastbourne. The remaining Dutch ships, though damaged, escaped. Holmes, who was wounded during the action, was knighted for his services.[41]

An English squadron under the command of William Coleman, captain of the Gloucester since 16 April,.[16] narrowly escaped capture early in May 1672. The squadron was on its way to join the Duke of Albemarle, when it was spotted, and 30 Dutch ships, commanded by Willem Joseph van Ghent, were suddenly sent in pursuit. Coleman's squadron succeeded in reaching the dockyard at Sheerness relatively unscathed.[42][43][44]

The Battle of Solebay (1672)

Gloucester was in the Blue Squadron (Van division) during the Battle of Solebay on 28 May 1672.[16] The battle has been described as one of the fiercest engagements in British naval history.[45]

The English and French fleets convened off Portsmouth on 5 May.[46] By 18 May, a confrontation between the combined French and English fleets (with a total of 6,018 guns), and the Dutch fleet (4,484 guns), seemed imminent.[47] During a delay of several days, the Dutch attempted unsuccessfully to lure the allies out to sea and towards the shallow waters of the Dutch coast. The allies' fleet instead made for the Suffolk coastal town of Southwold to obtain provisions and impress men from the town—nearby Sole Bay had the ability to provide ships with a safe haven,[48] and the English were sure that the westerly winds would prevent any sudden attack. It was several days before the Dutch located the allied fleet, but by 27 May they were able to report their position.[43]

When the Dutch fleet was spotted approaching the English coast—achieving the surprise that its commander Michiel de Ruyter had wished for—the sailors ashore were forced to rush back onto their ships.[49] The English and French fleets were roughly in formation, the Blue Squadron commanded by Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich to the north, the Duke of York with the Red Squadron in the centre, and the French fleet forming the White Squadron to the south. The French mistakenly sailed south and away from the English squadrons, so two separate battles took place for most of the day.[46]

During the battle, the Duke of York's flagship Prince was targeted by the Dutch, and was damaged enough for him to be forced firstly onto St. Michael, and then to London. The fighting continued throughout the afternoon, with ships locked in combat with each other.[50] The battle produced no clear victory for either side. There was heavy loss of life, with the English losses being the greatest. The Earl of Sandwich's Blue Squadron admirals Sir John Kempthorne and Sir Joseph Jordan lost contact with him after his ship the Royal James was surrounded, and he was killed when the Dutch destroyed the ship.[46][51]

Battles of Schooneveld and Battle of Texel (1673)

Gloucester was in Red squadron (Centre division) during the Battles of Schooneveld off the coast of the Netherlands in June 1673.[16] On 4 June, de Ruijter's Dutch fleet were sighted at anchor in Schooneveld by a combined Anglo-French fleet led by Prince Rupert. The battle commenced on 7 June. No ships were captured on either side, but once more the loss of life was heavy. On 14 June the Dutch ships emerged from port, and the second battle of the Schooneveld was fought. The Dutch eventually withdrew, although they had come off best, with neither side losing any ships.[52]

Gloucester took part in the Battle of Texel on 11 August 1673, after which she was sent at the end of the year to the Mediterranean.[16][53] Texel was the last battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War. An Allied force, consisting of the English and French fleets, met the Dutch fleet. The Allies' intention was to destroy the Dutch at sea as a precursor to a seaborne invasion of Holland.[54] The fleets, which met off the island of Texel, consisted of 86 ships under the command of Prince Rupert, and 60 Dutch ships, commanded by de Ruyter.[55][56][57]

After de Ruyter succeeded in separating the French from the main fleet, the French withdrew, and played no further major part in the action.[57] The two fleets were in parallel lines on the same tack, and de Ruyter concentrated on the English centre—and achieved almost equal odds. There was sharp action in the morning, broken off when each side steered to rejoin their rear squadrons. Tromp and Spragge faced one another in what amounted to a personal duel in the rear.[58] No large ships were lost, but many were seriously damaged, and 3,000 men were killed.[54][57][59]

Voyage to Scotland (1682)

_(studio_of)_-_James_II_(1633%E2%80%931701)%252C_as_Duke_of_York_-_337021_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

Gloucester was a valuable asset for the Royal Navy. From 1678–1680 she was comprehensively and expensively refitted at Portsmouth, a shortage of funds and materials having repeatedly delayed the work.[60][note 5]

In April 1682, Gloucester was due to be deployed, along with five other ships, to Tangier via Ireland, when Sir John Berry was appointed to command the ship, and was assigned to transport the Duke of York (the future King James II of England) and his party to Edinburgh.[60][61]

James's intention was to sail from Sheerness to Leith.[62] He intended to settle his affairs as Lord High Commissioner to the Parliament of Scotland, and collect his pregnant wife Mary of Modena (along with his daughter Anne from his previous marriage), before returning to London and taking up residence at his brother Charles's court. His plan would enable Mary to give birth in England, and so produce an English future heir to the throne.[63][64]

Amongst the courtiers who boarded the Gloucester were John Churchill (the future Duke of Marlborough), the Master-General of the Ordnance George Legge, James Dick (the Lord Provost of Edinburgh), and the Lord President of Scotland, James Graham, Marquess of Montrose.[65][note 6] No document listing those aboard the Gloucester itself has survived, adding to confusion about which of James's advisers were aboard.[66]

Gloucester, together with Ruby, Happy Return, Lark, Dartmouth and Pearl, and the royal yachts Mary, Katherine, Charlotte and Kitchen,[67][note 7] convened at Margate Road on 3 May.[62][66] The fleet left the Kent coast the following day, after having taken several hours to carry passengers and baggage across from the shore to the ships. A large crowd, along with the king and members of the royal court, were present to watch its departure of the fleet.[62][66]

Bad weather forced the Gloucester to moor up during the first night. As a signal for the fleet to drop anchor, she fired a gun, but three ships, misinterpreting the signal, sailed out to sea and never re-joined the fleet.[62]

Sinking

On the second evening, a dispute arose between the Duke and several officers—including Gloucester’s pilot, James Ayres—about the correct course to take.[13][62] Ayres was an experienced navigator who was well aware of the dangers posed by sandbanks in the waters surrounding the eastern coast of England. Wishing to avoid them, he advocated that the fleet sail close to the coast. The master of the Gloucester, Benjamin Holmes, advised avoiding the banks by using a deep-sea route. The Duke settled the matter when he decided upon a middle course.[68]

On the night of 5/6 May 1682, Gloucester was affected by strong winds blowing from the east.[69] At approximately 5.30 am the ship struck the Leman and Ower sandbank, about 45 kilometres (28 mi) off Great Yarmouth. Once it was realised she was aground, with the sandbank hidden in the dark, Gloucester fired a gun as a warning of the danger to the other ships. The ship bounced along the sandbank, which was in shallow water at low tide. The force of the ship against the sand broke off the rudder, and water rushed into the ship through a hole in the keel.[16][62][70] Less than an hour after she had run aground, the Gloucester sank.[67]

Rescue efforts

Partly through Berry's efforts and determination to stay with his ship until the end, the Duke was saved.[61] The ship's boats were lowered, enabling the Duke and some of his courtiers and advisors to reach the safety of the accompanying ships, which had already sent their boats to assist the stricken vessel.[13] James hesitated to leave the ship—he was convinced she would not be lost—finally abandoning the Gloucester once it was realised she could not be saved.[67]

His Royal Highness being gone into the Mary Yatcht, ordered all the Yatchts to Anchor, and to send off their Boats, as did likewise the Happy Return (the other three Frigats having lost Company) in the mean time the Glocester still beat on the Sand, her Head being cast aboat to the SW and by W, and the Water encreasing as high as the Gun Deck. However, the lifting of the Sea forced her off of the Sand, and she went into 15 fathom Water before we could let go our Anchor, which proved the loss of many poor Mens Lives. We Anchored and brought her Head up almost to Windward, we stil working with the Pumps and Bailing, but to no purpose; the Water encreasing so fast, that it was three Foot above the Gun-Deck, before we endeavoured to save our selves. She sunk so fast, that before the Boats could take out the Men (although there was great diligence used) the Ship was under Water, and several of our Men perished with her, Sir John Berry hardly escaping by a Rope over the Stern, into Captain Wybourn's Boat.

Protocol dictated that no-one could abandon a ship while there was still a member of the royal family aboard, so James' reluctance to leave the Gloucester, and his insistence that his strongbox containing his political documents should also be loaded onto his boat, delayed the start of the evacuation.[67][note 8] A second boat lowered from the Gloucester was quickly filled with passengers and crew.[67] Other boats managed to rescue more people, and many were saved, but between 130 and 250 sailors and passengers lost their lives. Amongst those drowned were Robert Ker, 3rd Earl of Roxburghe, Donough O'Brien, Lord Ibrackan, Lord Hopton,[13][62] and the Duke of York's brother-in-law James Hyde, who was a second lieutenant on the Gloucester. A letter published soon after the disaster revealed that nearly all the duke's retinue of servants had drowned as well.[72]

Aftermath

The Duke of York completed his voyage to Scotland on board the yacht Mary, accompanied by the Katherine and the Charlotte. On 7 May he reached Edinburgh, and was reunited with his family.[73][74]

The sinking of Gloucester "became key to the political fortunes and perceptions of the Duke".[75] He was later accused of having "taken particular care of his strong-box, his dogs, and his priests", while George Legge "with drawn sword kept off the other passengers".[13] James denied any responsibility for the loss of life, instead blaming the ship's pilot, James Ayres, and demanding that he be hanged immediately. Ayres was subsequently court-martialled and imprisoned, but released after being incarcerated for a year.[76]

Discovery of the wreck

.svg.png.webp)

In 2007, after a four-year-long search and thousands of miles at sea, the wreck of Gloucester was found 28 miles (45 km) off the Norfolk coast by a group of experienced divers underwater divers including brothers Lincoln and Julian Barnwell.[1][76][77] They retrieved a variety of artefacts, including the Ships Bell and a Bartmann jug.[78] The finding of a 1674 pewter teaspoon produced by the English manufacturer Daniel Barton ruled out the possibility of the wreck being HMS Kent, the only other Royal Navy ship of the period to be shipwrecked in the area.[note 9] Also found was a wine bottle with a seal of George Legge's family heraldic crest,[80] Other items found included navigational aids, clothing, footwear and other personal possessions. Some animal bones were discovered, but there were no signs of any human remains.[1]

The discovery of the ship's bell in 2012 enabled the identity of the wreck to be confirmed by the Receiver of Wreck and the UK Ministry of Defence.[1][81] The bell was inscribed with "1681", the year it was cast.[80]

The announcement of the finding of Gloucester was made in 2022, having had to wait until after the ship's identity was confirmed, but also to protect the site, which is located in international waters.[76] At a press conference in June 2022, Claire Jowitt, a maritime historian at the University of East Anglia, said the circumstances of the sinking meant that it "can be claimed as the single most significant historic maritime discovery since the raising of the Mary Rose in 1982", and that the discovery "would fundamentally change [our] understanding of 17th century social, maritime and political history”.[1][76] In 2023 a major exhibition was held in the City of Norwich, Norfolk.

Exhibition

.jpg.webp)

The Last Voyage of the Gloucester: Norfolk’s Royal Shipwreck 1682, an exhibition relating to the wreck, was held at the Castle Museum in Norwich from 25 February to 10 September 2023. The exhibition brought together artefacts from the wreck, new research into the context of the discovery, and artistic responses to it.[82][83]

Notes

- The contemporary third rate frigates built as part of the 1652 programme were Essex, Plymouth, Torrington, Newbury, Bridgewater, Lyme, Marston Moor, Langport, Fairfax, and Tredagh.[18]

- After Blake drew up papers attacking the army. Goodsonn brought charges against him in June 1656 and made him return to England, where Blake attempted to clear his name.[21]

- The ships in the 1658 English Baltic fleet were Swiftsure, Speaker, Plymouth, Newbury, Gloucester, Bridgewater, Essex, Newcastle, Ruby, Centurion, Nantwich, Preston, Adventure, Assurance, Maidstone, Expedition, Fagons, Forester, Elias, and Hind.[27]

- Clark became captain of the Gloucester in 1665, having been briefly the commander of the larger HMS St. George the previous year.[32]

- The number of guns was raised to 60 in 1677.[20]

- Power was moving from Charles to James, and to those courtiers who were chosen to accompany James to Edinburgh. The king by that time had already suffered a stroke.[66]

- The captain of the Ruby was Thomas Allin (or Allen).[67]

- The Duke's boat was underfilled to ensure the strongbox was not overturned in the sea.[67]

- HMS Kent was wrecked in October 1672 off Cromer.[79]

References

- "Shipwreck The Gloucester hailed most important since Mary Rose". BBC News. 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Lavery 2015, p. 13.

- Lavery 2003, p. 2.

- Capp 1989, pp. 79–80.

- Capp 1989, p. 52.

- Capp 1989, pp. 66–68.

- Capp 1989, p. 72.

- "Museum number 1888,0612.72". British Museum. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Lavery 2015, p. 15.

- Dull 2009, p. 5.

- Gardiner 2013, p. 11.

- Dull 2009, pp. 2–3.

- "Glocester". Heritage Gateway. Historic England. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Lavery 2003, p. 221.

- Lavery 2003, p. 159.

- Winfield 2009, p. 1661.

- "The Gloucester Project: The Cromwellian Navy and the Building of the Gloucester". The Gloucester Project. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "Objectives". The Gloucester Project. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Winfield 2009, Contents.

- Winfield 2009, p. 408.

- Lecky 1914, p. 165.

- Capp 1989, p. 88.

- Dixon 1885, pp. 125, 225.

- Capp 1989, p. 184.

- Capp 1989, p. 108.

- Anderson 1929, pp. xiv, xviii.

- Anderson 1929, p. xiv.

- Anderson 1929, p. xv.

- "Battle Of Lowestoft 1665". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- Rodger 2004, pp. 69–70.

- "The Battle of Lowestoft, 3 June 1665, Showing HMS 'Royal Charles' and the 'Eendracht'". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- Charnock 1794, p. 10.

- Charnock 1794, pp. 10–11.

- Harris 2017, p. 43.

- "Four Days Battle 1666". Heritage Gateway. Historic England. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Rodger 2004, p. 72.

- Rodger 2004, p. 74.

- Harris 2017, p. 49.

- Rodger 2004, p. 75.

- Rodger 2004, pp. 75, 77.

- Lecky 1914, pp. 165–166.

- Lecky 1914, p. 166.

- Corbett 1908, pp. 15–16.

- Davies, Caroline (27 January 2023). "'Remarkable': Eastbourne shipwreck identified as 17th-century Dutch warship". Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

A remarkably preserved shipwreck known only as the "unknown wreck off Eastbourne" has finally been identified as the 17th-century Dutch warship Klein Hollandia... Its identity has been confirmed after painstaking research by archaeologists and scientists after its initial discovery in 2019, having lain 32 metres (105ft) underwater on the seabed since 1672. the Klein Hollandia warship which was built in 1656 and owned by the Admiralty of Rotterdam.

- Munn 2017, p. 81.

- Rodger 2004, p. 81.

- Munn 2017, pp. 55, 57.

- Barry 2018, pp. 81, 86.

- Munn 2017, p. 86.

- Munn 2017, p. 87.

- Munn 2017, p. 88.

- Lecky 1914, pp. 166–167.

- Burns 1986, p. 92.

- "The Battle of the Texel, 11–21 August 1673". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "The Battle of The Texel, 11 August 1673". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Rodger 2004, pp. 83–85.

- Mahan 1987, pp. 152–153.

- Rodger 2004, pp. 84–85.

- "The battle of the Texel (Kijkdum) 11/21 August 1673". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Jowitt 2022, p. 13.

- Davies 2008.

- "The sinking of HMS Gloucester". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Jowitt 2022, pp. 729, 737.

- Curtis 1972, pp. 12–17.

- "The Gloucester Project: Disaster at Sea". The Gloucester Project. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Jowitt 2022, p. 738.

- Jowitt 2022, p. 739.

- "The Gloucester". University of East Anglia. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Pickford 2021, p. 95.

- Pickford 2021, pp. 96–98.

- "(untitled)". The London Gazette. No. 1720. May 1682. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Jowitt 2022, p. 740.

- Jowitt 2022, p. 728.

- Pickford 2021, pp. 107–108.

- Jowitt 2022, p. 729.

- Thomas, Tobi (10 June 2022). "Wreck of Royal Navy warship sunk in 1682 identified off Norfolk coast". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Coates, Liz (10 June 2022). "The brothers who first read about the Gloucester in a book called 'Shipwreck Index of the British Isles' spent a fortune searching for lost royal ship". Great Yarmouth Mercury. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Coates, Liz (10 July 2022). "HMS Gloucester: Six fascinating finds from royal shipwreck". Great Yarmouth Mercury. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Lavery 2003, p. 160.

- "Royal warship's wreckage found off coast of Norfolk after sinking in 1682". Worcester News. PA Media. 10 June 1022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Hui, Sylvia (10 June 2022). "Wreck of 17th-century royal warship found off UK coast". Associated Press. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- "Royal shipwreck inspires new research". University of East Anglia. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- "The Last Voyage of the Gloucester: Norfolk's Royal Shipwreck, 1682". Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Sources

- Anderson, R.C., ed. (1929). The Journal of Edward Mountagu, first Earl of Sandwich, admiral and general at sea, 1659–1665. London: Navy Records Society. OCLC 1880123.

- Barry, Quintin (2018). From Solebay to the Texel: the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672-1674. Warwick, UK: Helion Limited. ISBN 978-19116-2-803-3.

- Burns, K.V. (1986). Badges and Battle Honours of H.M. Ships. Liskeard, UK: Maritime Books. ISBN 978-0-907771-26-5.

- Capp, Bernard S. (1989). Cromwell's Navy: the fleet and the English Revolution, 1648-1660. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820115-1. 52 61

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Charnock, John (1794). Biographia navalis: or, memoirs of the lives and characters of officers of the navy of Great Britain, from the year 1660 to the present time. Vol. 1. London: R. Faulder. OCLC 960916577.

- Corbett, Julian S. (1908). A Note on the Drawings in the Possession of the Earl of Dartmouth: illustrating the Battle of Sole Bay, May 28, 1672, and the Battle of the Texel, August 11, 1673. London: Navy Records Society. OCLC 492244.

- Curtis, Gila (1972). The Life and Times of Queen Anne. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-02979-9-571-5.

- Davies, J.D. (2008). "Berry, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2265. OCLC 56568095. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Dull, Jonathan R. (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line: British and French Navies 1650–1815. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-18483-2-549-4.

- Dixon, Hepworth (1885) [1852]. Robert Blake: Admiral and General at Sea. London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 1431782.

- Gardiner, Robert (2013). The Sailing Frigate: a history in ship models. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-17838-3-068-8.

- Harris, Simon (2017). The Other Norfolk Admirals: Myngs, Narbrough and Shovell. Helion Limited. ISBN 978-19121-7-422-5.

- Jowitt, Claire (2022). "The Last Voyage of the Gloucester (1682): The Politics of a Royal Shipwreck". The English Historical Review. 137 (586): 728–762. doi:10.1093/ehr/ceac127.

- Lavery, Brian (2003). The Ship of the Line. Vol. 1: The Development of the Battlefleet 1650–1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-252-3.

- Lavery, Brian (2015). The Ship of the Line: a history in ship models. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-18483-2-214-1.

- Lecky, Halton Stirling (1914). The Kings Ships. Vol. 3. London: Horace Muirhead. OCLC 2135014.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1987) [1890]. The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-04862-5-509-5.

- Munn, Geoffrey· (2017). Southwold: An Earthly Paradise. ACC Art Books Limited. ISBN 978-18514-9-855-0.

- Pickford, Nigel (2021). Samuel Pepys and the Strange Wrecking of the Gloucester. Cheltenham, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-07509-9-753-9.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean: a naval history of Britain 1649-1815. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-07139-9-411-7.

- Winfield, Rif (2009). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1603–1714: design, construction, careers and fates. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-040-6.

- Attribution

This article includes data released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported UK: England & Wales Licence, by the National Maritime Museum, as part of the Warship Histories project.

Further reading

- Burnet, Gilbert; Airy, Osmund (1900) [1734]. Burnet's History of My Own Time. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 326–328. OCLC 613786164 – via Internet Archive.

- Ellis, Henry (1827). Original letters, illustrative of English history; including numerous royal letters; from autographs in the British Museum, and one or two other collections. With notes and illustrations by Henry Ellis. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London: Printed for Harding and Lepard. pp. 67–73.

- Love, Harold (1984). "The Wreck of the Gloucester". The Musical Times. 125 (1694): 194–195. doi:10.2307/963562. JSTOR 963562 – via JSTOR.

- Millard, Victor F. L. (1944). The Warships of Gloucester: (H.M. Ships Gloucester, 1654–1941) and the Severn and Naval Defence (2nd ed.). Gloucester, UK: Gloucester Library and Museum Committee. OCLC 1039987572.

- Pepys, Samuel (1926) [1680–1683]. Tanner, Joseph Robson (ed.). Samuel Pepys's Naval Minutes. Vol. 60. London: Navy Records Society – via Internet Archive.

- Redding, Benjamin W. D. (2023). "The Western Design Revised: Death, Dissent, and Discontent on the Gloucester, 1654–1656". The Historical Journal: 1–26. doi:10.1017/S0018246X23000262. ISSN 1469-5103.

- Singer, Samuel Weller, ed. (1828). The Correspondence of Henry Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, and his Brother Laurence Hyde, Earl of Rochester. Vol. 1. London: H. Colburn. pp. 67–73.

External links

- The Gloucester Project—The project by the University of East Anglia to provide a history of the Gloucester warship

- The Gloucester 1682 Trust website