Haemophilia C

Haemophilia C (also known as plasma thromboplastin antecedent (PTA) deficiency or Rosenthal syndrome) is a mild form of haemophilia affecting both sexes, due to factor XI deficiency.[4] It predominantly occurs in Ashkenazi Jews. It is the fourth most common coagulation disorder after von Willebrand's disease and haemophilia A and B. In the United States, it is thought to affect 1 in 100,000 of the adult population, making it 10% as common as haemophilia A.[1][5]

| Haemophilia C | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Plasma thromboplastin antecedent (PTA) deficiency, Rosenthal syndrome |

| |

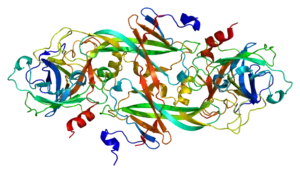

| Haemophilia C caused by deficiency in Factor XI[1] | |

| Specialty | Haematology |

| Symptoms | Oral bleeding[2] |

| Causes | Deficiency of coagulation factor XI[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Prothrombin time[1] |

| Prevention | Physical activity precautions[1] |

| Treatment | tranexamic acid[3] |

Signs and symptoms

In terms of the signs/symptoms of haemophilia C, unlike individuals with Haemophilia A and B, people affected by it are not ones to bleed spontaneously. In these cases, haemorrhages tend to happen after a major surgery or injury.[6] However, people affected with haemophilia C might experience symptoms closely related to those of other forms of haemophilia such as the following:[2]

- Oral bleeding.

- Nosebleeds

- Blood in the urine

- Post-partum bleeding (20% of cases)

- Tonsils (bleeding)

Cause

Haemophilia C is caused by a deficiency of coagulation factor XI and is distinguished from haemophilia A and B by the fact it does not lead to bleeding into the joints. Furthermore, it has autosomal recessive inheritance, since the gene for factor XI is located on chromosome 4 (near the prekallikrein gene); and it is not completely recessive, individuals who are heterozygous also show increased bleeding.[1][7]

Many mutations exist, and the bleeding risk is not always influenced by the severity of the deficiency. Haemophilia C is occasionally observed in individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus, because of inhibitors to the FXI protein.[1][8]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of haemophilia C (factor XI deficiency) is centered on prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). One will find that the factor XI has decreased in the individual's body. In terms of differential diagnosis, one must consider: haemophilia A, haemophilia B, lupus anticoagulant and heparin contamination.[4][9] The prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time should completely correct with a 1:1 mixing study with normal plasma if haemophilia C is present; in contrast, if a lupus anticoagulant is present as the cause of a prolonged aPTT, the aPTT will not correct with a 1:1 mixing study.

Treatment

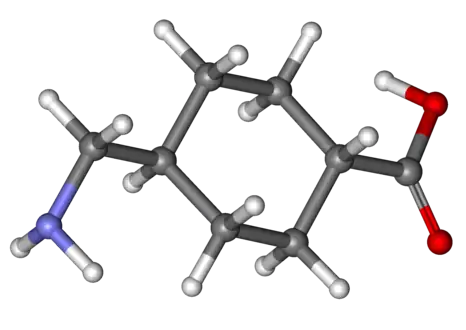

In terms of haemophilia C medication tranexamic acid is often used for both treatment after an incident of bleeding and as a preventive measure to avoid excessive bleeding during oral surgery.[3]

Treatment is usually not necessary, except in relation to operations, leading to many of those having the condition not being aware of it. In these cases, fresh frozen plasma or recombinant factor XI may be used, but only if necessary.[4][10]

Those affected may often develop nosebleeds, while females can experience unusual menstrual bleeding which can be avoided by taking birth control such as: IUDs and oral or injected contraceptives to increase coagulation ability by adjusting hormones to levels similar to pregnancy.

Cyklokapron (Tranexamic acid)

Cyklokapron (Tranexamic acid) Fresh Frozen Plasma

Fresh Frozen Plasma

See also

References

- "Hemophilia C: Background, Etiology, Epidemiology". December 9, 2021 – via eMedicine.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Seligsohn, U. (2009-07-01). "Factor XI deficiency in humans". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 7: 84–87. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03395.x. ISSN 1538-7836. PMID 19630775. S2CID 37670882.

- Anderson, J. a. M.; Brewer, A.; Creagh, D.; Hook, S.; Mainwaring, J.; McKernan, A.; Yee, T. T.; Yeung, C. A. (23 November 2013). "Guidance on the dental management of patients with haemophilia and congenital bleeding disorders". British Dental Journal. 215 (10): 497–504. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1097. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 24264665.

- "Factor XI Deficiency: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2018-07-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Factor XI deficiency | Disease | Overview | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- Gomez, K.; Bolton-Maggs, P. (2008-11-01). "Factor XI deficiency". Haemophilia. 14 (6): 1183–1189. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01667.x. ISSN 1365-2516. PMID 18312365. S2CID 27557689.

- "OMIM Entry - # 612416 - FACTOR XI DEFICIENCY". omim.org. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Kitchens, Craig S.; Konkle, Barbara A.; Kessler, Craig M. (2013-02-20). Consultative Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 70. ISBN 978-1455733293.

- RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Congenital factor XI deficiency Hemophilia C". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Orkin, Stuart H.; Nathan, David G.; Ginsburg, David; Look, A. Thomas; Fisher, David E.; IV, Samuel Lux (2014-11-14). Nathan and Oski's Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 136. ISBN 9780323291774.

Further reading

- Zucker, M.; Zivelin, A.; Landau, M.; Salomon, O.; Kenet, G.; Bauduer, F.; Samama, M.; Conard, J.; Denninger, M.-H.; Hani, A.-S.; Berruyer, M.; Feinstein, D.; Seligsohn, U. (1 October 2007). "Characterization of seven novel mutations causing factor XI deficiency". Haematologica. 92 (10): 1375–1380. doi:10.3324/haematol.11526. ISSN 0390-6078. PMID 18024374.

- Orkin, Stuart H.; Nathan, David G. (2008). Nathan and Oski's Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1416034308. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (2016). Goldman-Cecil Medicine Elsevieron VitalSource. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323322850. Retrieved 12 July 2016.