Old Kannada

Old Kannada or Halegannada (Kannada: ಹಳೆಗನ್ನಡ, romanized: Haḷegannaḍa) is the Kannada language which transformed from Purvada halegannada or Pre-old Kannada during the reign of the Kadambas of Banavasi (ancient royal dynasty of Karnataka 345–525 CE).[1]

| Old Kannada | |

|---|---|

| Era | evolved into Kannada ca. 500 CE |

Dravidian

| |

| Kadamba script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qkn | |

| Glottolog | oldk1250 |

The Modern Kannada language has evolved in four phases over the years. From the Purva Halegannada in the 5th century (as per early epigraphic records), to the Halegannada (Old Kannada) between the 9th and 11th century, the Nadugannada (Middle Kannada) between the 12th and 17th century (as evidenced by Vachana literature), it has evolved to the present day Hosagannada (Modern Kannada) from 18th century to present. Hosagannada (Modern Kannada) is the official language of the state of Karnataka and is one of the 22 official national languages of the Republic of India and is the native language of approximately 65% of Karnataka's population.[2]

Etymology

Halegannada is derived from two Kannada terms, haḷe and Kannaḍa. Haḷe, a prefix in Kannada, means old or ancient. Using the concept of sandhi found in Kannada grammar (which is also found in many other Indian languages), in which the sounds and spellings of two or more words are changed and combined, depending on those words and sounds, the k becomes g (ādeśa sandhi) and so haḷe and Kannaḍa together becomes Haḷegannaḍa.

Origin

Purvada HaleGannada (Pre-old Kannada)

A 5th century copper coin was discovered at Banavasi with an inscription in the Kannada script, one of the oldest such coins ever discovered.

In a report published by the Mysore Archaeological Department in 1936, Dr. M. H. Krishna, (the Director of Archaeology of the erstwhile Mysore state) who discovered the inscription in 1936 dated the inscription to 450 CE. This inscription in old-Kannada was found in Halmidi village near Hassan district. Many other inscriptions having Kannada words had been found like the Brahmagiri edict of 230 BCE by Ashoka. But this is the first full scale inscription in Kannada. Kannada was used in the inscriptions from the earliest times and the Halmidi inscription is considered to be the earliest epigraph written in Kannada.[3][4]

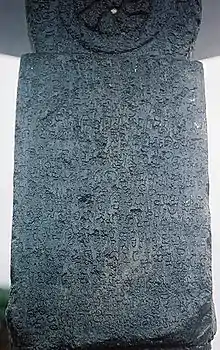

This inscription is generally known as the Halmidi inscription and consists of sixteen lines carved on a sandstone pillar. It has been dated to 450 CE and demonstrates that Kannada was used as a language of administration at that time.[5][6]

Dr K.V.Ramesh has hypothesized that, compared to possibly contemporaneous Sanskrit inscriptions, "Halmidi inscription has letters which are unsettled and uncultivated, no doubt giving an impression, or rather an illusion, even to the trained eye, that it is, in date, later than the period to which it really belongs, namely the fifth century A.D."[7]

The original inscription is kept in the Office of the Director of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of Karnataka, Mysore,[8] and a fibreglass replica has been installed in Halmidi. A mantapa to house a fibreglass replica of the original inscription has been built at Halmidi village. The Government has begun to promote the village as a place of historical interest.[9]

Evidence from edicts during the time of Ashoka the Great suggests that the Kannada script and its literature were influenced by Buddhist literature. The Halmidi inscription, the earliest attested full-length inscription in the Kannada language and script, is dated to 450 CE while the earliest available literary work, the Kavirajamarga, has been dated to 850 CE. References made in the Kavirajamarga, however, prove that Kannada literature flourished in the Chattana, Beddande and Melvadu metres during earlier centuries.[10]

The 5th century Tamatekallu inscription of Chitradurga, and the Chikkamagaluru inscription of 500 CE are further examples.[11][12][13]

Purvahalegannada grammar

The grammar of the ancient Kannada language was in general more complex than of modern Kannada which has some similarities of old Tamil and Sanskrit. Phonology wise, there was full use of the now obsolete letters ೞ (l̠a) and ಱ (r̠a) (i.e. same as in Tamil and Malayalam). Aspirated letters were not normally used.

Words (nouns and verbs etc.) were permitted to end in consonants, the permitted consonants being: ನ್ (n), ಣ್ (ṇ), ಲ್ (l), ಳ್ (ḷ), ೞ್ (l̠), ರ್ (r), ಱ್ (r̠), ಯ್ (y), and ಮ್ (m). If words were borrowed from Sanskrit, they were changed to fit the tongue and style of the Kannada language.

Nouns declined according to how they ended (i.e. which type of vowel or consonant). They were grouped into human and non-human (animate and inanimate). Examples of terminations of declension are: ಮ್, ಅನ್, ಅಳ್, ಅರ್, ಒನ್, ಒರ್, ಗಳ್, ಗೆ, ಅತ್ತಣಿಂ, ಇನ್, ಇಂದೆ, ಅಲ್, ಉಳ್ and ಒಳ್. Most terminations were suffixed to the 'oblique case' of nouns.

The plurals of human and non-human nouns differed; non-human nouns took the suffix ಗಳ್ whilst human nouns took the suffix ಅರ್. These two suffixes had tens and tens of varied forms. Occasionally, with human nouns and nouns normally taking only ಅರ್, double plurals were formed using both the suffixes e.g. ಜನ (person) + ಅರ್ + ಕಳ್ = ಜನರ್ಗಳ್ (people).

There was a large variety of personal pronouns. The first-person plural had a clusivity distinction, i.e. ನಾಂ – We (including person being talked to); ಎಂ – We (excluding person being talked to). There were three degrees of proximity distinction, usually shown by the three vowels: ಇ – proximate space; ಉ – intermediate space; ಅ – distant space.

Numbers and natural adjectives (i.e. true adjectives) were often compounded with nouns, in their ancient, crude forms. Examples of these crude forms are: One – ಒರ್, ಓರ್; Two – ಇರ್, ಈರ್; Big – ಪೇರ್; Cold – ತಣ್. Examples of compounds are: ಓರಾನೆ – One elephant, ಇರ್ಮೆ – Two times/Twice, ಪೇರ್ಮರಂ – large tree, ತಣ್ಣೀರ್ – cold water

As of verbs, there was a large variety of native Kannada verbs. These verbs existed as verbal roots, which could be modified into conjugations, nouns etc. Many verbs existed which are now out of use. e.g. ಈ – To give; ಪೋರ್ – To fight; ಉಳ್ – To be, To possess.

Verbs were conjugated in the past and future. The present tense was a compound tense, and was artificial (i.e., it wasn't in the language originally); it was made using forms of the verb ಆಗು/ಆ (= to become). There was a negative mood (e.g. from ಕೇಳ್ – To listen, ಕೇಳೆನ್ = I do not listen, I have not listened, I won't listen). Note that the negative mood is devoid of time aspect, and could and can be used with a past, present, or future meaning. Apart from the negative mood, all tenses were formed using personal terminations attached to participles of verbs.

Causative verbs were formed using ಚು, ಸು, ಇಚು, ಇಸು, ಪು, (ದು – obsolete, only present in very ancient forms). The first two and last were originally used only in the past tenses, the middle two in the non-past (i.e. present), and the penultimate one in the future. This reflects the Dravidian linguistic trait of causativity combined with time aspect. This trait was eventually lost.

Appellative verbs also existed, which were nouns used as verbs by suffixing personal terminations, e.g. ಅರಸನ್ (king) + ಎನ್ (personal termination for 'I') = ಅರಸನೆನ್ (I am the king)

Nouns were formed from verbal roots using suffixes and these nouns were usually neuter gender and abstract in meaning, e.g. suffixes ಕೆ, ಗೆ, ವು, ವಿ, ಪು, ಪಿ, ಮೆ, ಅಲ್; Root ಕಲ್ (To learn) + ಪಿ (Suffix) = ಕಲ್ಪಿ (Knowledge, learning) Also, negative nouns could be formed from negative verb-bases e.g. ಅಱಿಯ (Negative base of root ಅಱಿ, inferred meaning not-knowing, Literally: Yet-to-know) + ಮೆ (suffix) = ಅಱಿಯಮೆ (Lack of knowledge, Ignorance, Literally: Yet-to-know-ness)

Regarding adjectives, Kannada had and still has a few native words that can be classed as true adjectives. Apart from these, mentioned in 'Numbers and natural adjectives', Kannada used and uses the genitive of nouns and verbal derivatives as adjectives. e.g. ಚಿಕ್ಕದ ಕೂಸು – Small baby (literally: baby of smallness). It may be said that there are not real 'adjectives' in Kannada, as these can be called moreover, nouns of quality.

Halmidi textual analysis

The inscription is in verse form indicating the authors of the inscription had a good sense of the language structure.[14] The inscription is written in pre-old Kannada (Purvada-halegannada), which later evolved into old Kannada (Halegannada), middle Kannada and eventually modern Kannada.[15] The Halmidi inscription is the earliest evidence of the usage of Kannada as an administrative language.[16]

Text

The pillar on which the inscription was written stands around 4 feet (1.2 m) high. Its top has been carved into an arch, onto which the figure of a wheel has been carved, which is probably intended to represent the Sudarshana Chakra of Vishnu.[17] The following lines are carved on the front of the pillar:

- jayati śri-pariṣvāṅga-śārṅga vyānatir-acytāḥ dānav-akṣṇōr-yugānt-āgniḥ śiṣṭānān=tu sudarśanaḥ

- namaḥ śrīmat=kadaṁbapan=tyāga-saṁpannan kalabhōranā ari ka-

- kustha-bhaṭṭōran=āḷe naridāviḷe-nāḍuḷ mṛgēśa-nā-

- gēndr-ābhiḷar=bhbhaṭahar=appor śrī mṛgēśa-nāgāhvaya-

- r=irrvar=ā baṭari-kul-āmala-vyōma-tārādhi-nāthann=aḷapa-

- gaṇa-paśupatiy=ā dakṣiṇāpatha-bahu-śata-havan=ā-

- havuduḷ paśupradāna-śauryyōdyama-bharitōn=dāna pa-

- śupatiyendu pogaḷeppoṭṭaṇa paśupati-

- nāmadhēyan=āsarakk=ella-bhaṭariyā prēmālaya-

- sutange sēndraka-bāṇ=ōbhayadēśad=ā vīra-puruṣa-samakṣa-

- de kēkaya-pallavaraṁ kād=eṟidu pettajayan=ā vija

- arasange bāḷgaḻcu palmaḍiuṁ mūḷivaḷuṁ ko-

- ṭṭār baṭāri-kuladōn=āḷa-kadamban kaḷadōn mahāpātakan

- irvvaruṁ saḻbaṅgadar vijārasaruṁ palmaḍige kuṟu-

- mbiḍi viṭṭār adān aḻivornge mahāpatakam svasti

The following line is carved on the pillar's left face:

- bhaṭṭarg=ī gaḻde oḍḍali ā pattondi viṭṭārakara

Epigraphy

While Kannada is attested epigraphically from the mid-1st millennium CE as Halmidi script of Purvada HaleGannada (Pre-old Kannada), and literary Old Kannada Halekannada flourished in the 9th to 10th century Rashtrakuta Dynasty.[18]

More than 800 inscriptions are found at Shravanabelagola dating from various points during the period from 600 to 1830 CE. A large number of these are found at Chandragiri, and the rest can be seen at Indragiri. Most of the inscriptions at Chandragiri date back to before the 10th century. The inscriptions include text in the Kannada, Sanskrit, Tamil, Marathi, Marwari and Mahajani languages. The second volume of Epigraphia Carnatica, written by Benjamin L. Rice is dedicated to the inscriptions found here. The inscriptions that are scattered around the area of Shravanabelagola are in various Halegannada (Old Kannada) and Purvadahalegannada (Pre-Old Kannada) characters. Some of these inscriptions mention the rise to power of the Gangas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar empire and Mysore Wodeyars. These inscriptions have immensely helped modern scholars in properly understanding the nature, growth and development of the Kannada language and its literature.

The earliest full-length Kannada copper plates in Old Kannada script (early 8th century) belongs to the Alupa King Aluvarasa II from Belmannu, South Kanara district and displays the double crested fish, his royal emblem.[19] The oldest well-preserved palm leaf manuscript is in Old Kannada and is that of Dhavala, dated to around the 9th century, preserved in the Jain Bhandar, Mudbidri, Dakshina Kannada district.[26] The manuscript contains 1478 leaves written using ink.

The written Kannada language has come under various religious and social influences in its 1600 years of known existence. Linguists generally divide the written form into four broad phases.

From the 9th to the 14th centuries, Kannada works were classified under Old Kannada (Halegannada). In this period Kannada showed a high level of maturity as a language of original literature.[20] Mostly Jain and Saivite poets produced works in this period. This period saw the growth of Jain puranas and Virashaiva Vachana Sahitya or simply vachana, a unique and native form of literature which was the summary of contributions from all sections of society.[21][22] Early Brahminical works also emerged from the 11th century.[23] By the 10th century, Kannada had seen its greatest poets, such as Pampa, Sri Ponna and Ranna, and its great prose writings such as the Vaddaradhane of Shivakotiacharya, indicating that a considerable volume of classical prose and poetry in Kannada had come into existence a few centuries before Kavirajamarga (c.850).[24] Among existing landmarks in Kannada grammar, Nagavarma II's Karnataka-bhashabhushana (1145) and Kesiraja's Shabdamanidarpana (1260) are the oldest.[25][26]

Epigraphia Carnatica by B.L.Rice published by the Mysore Archeology department in 12 volumes contains a study of inscriptions from 3rd century until the 19th century. These inscriptions belonged to different dynasties that ruled this region such as Kadambas, Western Chalukyas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar kings, Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan and the Mysore Wodeyars. The inscriptions found were mainly written in Kannada language but some have been found to be written in languages like Tamil, Sanskrit, Telugu, Urdu and even Persian and have been preserved digitally as a CD-ROM in 2005.[27]

Information dissemination

Linguist Lingadevaru Halemane announcing the launching of the lecture series in Bangalore in June 2007 on Halegannada, noted that there was documentary proof about Kannada being existent even in 250 BCE, and that there were enough grounds for giving classical status to Kannada. The lecture series unveiled the indigenous wealth of the language, the stone inscriptions belonging to different periods, besides the folk and medicinal knowledge people possessed in this region in that age. This series of lectures would be extended to other parts of the state.[28]

The central Government of India formed a new category of languages called Classical languages, in 2004. Tamil was the first to be classified so. Sanskrit was added to the category a year later. The four criteria to declare Kannada as a Classical language, stated below, which are stated to be fulfilled has prompted action to seek recognition from the Central Institute of Indian Languages[29]

- Recorded history of over a thousand five hundred years

- High antiquity of a language's early texts

- An body of ancient literature, which is considered a valuable heritage by generation of speakers

- The literary tradition has to be original and not borrowed from another speech community and the language could be distinct from its "later and current" forms or it could be continuous.

The classical tag equates a language to all ancient languages of the world. This is a qualification that helps in the establishment of its research and teaching chairs in any university in the world. It also provides a larger spectrum for its study and research, creates a large number of young researchers and ensures republication of out-of-print classic literature.

An Expert Committee comprising eminent researchers, distinguished academicians, reputed scholars, well known historians and renowned linguists prepared a report by collecting all the documents and credentials to prove the claim of its antiquity. This document was submitted to the Committee of Linguistic Experts set up in November 2004 by the Government of India for recognition of Kannada as a classical language. The Expert Committee Report of the Government of Karnataka titled "Experts Report submitted to the Government of Karnataka on the subject of the recognition of Kannada as a classical Language" published in February 2007 by Kannada Pustaka Pradhikara of The Department of Kannada and Culture, Government of Karnataka, M.S. Building, Bangalore.

The Expert Committee of the Government of India has examined the above submissions made in the report of the Karnataka Government, and vide their Notification No 2-16-/2004-Akademics dated 31 October 2008 have stated that

"It is hereby notified that the "Telugu Language" and the "Kannnada Language" satisfy the above x criteria and will henceforth be classified as 'Classical Languages'. The notification is subject to the decision in Writ Petition no 18180 of 2008 in the High Court of jurisdiction at Madras.

A newspaper report has confirmed the fact that the Government of India has accorded, on 31 October 2008, the Classical Language status to Kannada and Telugu languages based on the recommendation of the nine-member Committee of Linguistic Experts.[30]

References

- "OurKarnataka.com: History of Karnataka: Kadambas of Banavasi". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "The Karnataka Local Authorities (Official Language) Act, 1981" (PDF). Official website of Government of Karnataka. Government of Karnataka. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "Language of the Inscriptions – Sanskrit and Dravidian – Archaeological Survey of India". Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "Halmidi inscription". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 31 October 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- "Halmidi inscription proves antiquity of Kannada: Moily". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 October 2004. Archived from the original on 1 December 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- K.V. Ramesh, Chalukyas of Vatapi, 1984, Agam Kala Prakashan, Delhi OCLC 13869730 OL 3007052M LCCN 84-900575 ASIN B0006EHSP0 p10

- Ramesh 1984b, p. 58

- Gai 1992, p. 297

- bgvss (3 November 2003). "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 November 2003.

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 12, 17.

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p6

- Rice (1921), p13

- Govinda Pai in Bhat (1993), p102

- Datta 1988, p. 1474

- M. Chidananda Murthy, Inscriptions (Kannada) in Datta 1988, p. 1717

- Ramesh 1984a, p. 10

- Khajane 2006

- "Awardees detail for the Jnanpith Award". Official website of Bharatiya Jnanpith. Bharatiya Jnanpith. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- Gururaj Bhat in Kamath (2001), p97

- The earliest cultivators of Kannada literature were Jain scholars (Narasimhacharya 1988, p17)

- More than two hundred contemporary Vachana poets have been recorded (Narasimhacharya 1988, p20)

- Sastri (1955), p361

- Durgasimha, who wrote the Panchatantra, and Chandraraja, who wrote the Madanakatilaka, were early Brahmin writers in the eleventh century under Western Chalukya King Jayasimha II (Narasimhacharya 1988, p19)

- Sastri (1955), p355

- Sastri (1955), p359

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p19

- Mysore. Dept. of Archaeology; Rice, B. Lewis (Benjamin Lewis); Narasimhacharya, Ramanujapuram Anandan-pillai. "Epigraphia carnatica. By B. Lewis Rice, Director of Archaeological Researches in Mysore". Bangalore Mysore Govt. Central Press – via Internet Archive.

- "Deccan Herald – Lecture series on Halegannada". Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "viggy.com Kannada Film Discussion Board – exclusive platform for Kannada cinema – Why kannada deserved classical language". Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Centre grants classical language status to Telugu, Kannada". 1 November 2008 – via www.thehindu.com.

External links

- Epigraphia Carnatica, online copy of the 1898 edition. (archive.org)

External sources

- The Expert Committee Report of the Government of Karnataka titled "Experts Report submitted to the Government of Karnataka on the subject of the recognition of Kannada as a classical Language" published in February 2007 by Kannada Pustaka Pradhikara of The Department of Kannada and Culture, Government of Karnataka, M.S. Building, Bangalore.

- Government of India Notification No 2-16-/2004-Akademics dated 31 October 2008.