Ham (chimpanzee)

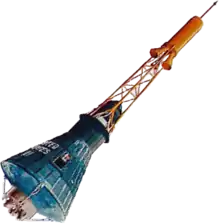

Ham (July 1957 – January 19, 1983), a chimpanzee also known as Ham the Chimp and Ham the Astrochimp, was the first great ape launched into space. On January 31, 1961, Ham flew a suborbital flight on the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission, part of the U.S. space program's Project Mercury.[1][2]

.jpg.webp) Ham in January 1961, just before his suborbital flight into space | |

| Species | Common chimpanzee |

|---|---|

| Sex | Male |

| Born | July 1957 French Cameroon |

| Died | January 19, 1983 (aged 25) North Carolina Zoo, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Resting place | Museum of Space History New Mexico |

| Known for | First hominid in space |

Ham's name is an acronym for the laboratory that prepared him for his historic mission—the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center, located at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, southwest of Alamogordo. His name was also in honor of the commander of Holloman Aeromedical Laboratory, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton "Ham" Blackshear.[3][4]

Early life

Ham was born in July 1957 in French Cameroon (now Cameroon),[5][6] captured by animal trappers and sent to the Rare Bird Farm in Miami, Florida. He was purchased by the United States Air Force and brought to Holloman Air Force Base in July 1959.[5]

There were originally 40 chimpanzee flight candidates at Holloman. After evaluation, the number of candidates was reduced to 18, then to six, including Ham.[7]: 245–246 Officially, Ham was known as No. 65 before his flight,[8] and only renamed "Ham" upon his successful return to Earth. This was reportedly because officials did not want the bad press that would come from the death of a "named" chimpanzee if the mission were a failure.[9] Among his handlers, No. 65 had been known as "Chop Chop Chang".[10][9]

Training and mission

Beginning in July 1959, the two-year-old chimpanzee was trained under the direction of neuroscientist Joseph V. Brady at Holloman Air Force Base Aero-Medical Field Laboratory to do simple, timed tasks in response to electric lights and sounds.[11] During his pre-flight training, Ham was taught to push a lever within five seconds of seeing a flashing blue light; failure to do so resulted in an application of a light electric shock to the soles of his feet, while a correct response earned him a banana pellet.[12]

While Ham was the first great ape, he was not the first animal to go to space, as there were many other types of animals that left Earth's atmosphere before him. However, none of these other animals could provide the significant insight that Ham could provide. One of the reasons that a chimpanzee was chosen for this mission was because of their many similarities to humans. Some of their similarities include: similar organ placement inside the body and having a response time to a stimulus that was very similar to that of humans (just a couple of deciseconds slower). Through the observations of Ham scientists would gain a better understanding of the possibility of sending humans into space.[8]

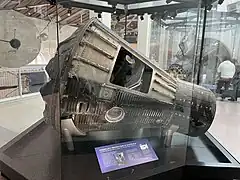

On January 31, 1961, Ham was secured in a Project Mercury mission designated MR-2 and launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a suborbital flight.[1][12]: 314–315 At the time of the flight Ham was only a three and a half year old chimpanzee. He was fairly young but he was more than prepared for this mission. He had eighteen months of rigorous training, and even if something were to go wrong,[13] Ham's vital signs and tasks were monitored by sensors and computers on Earth.[14] The flight did not go one hundred percent as they had planned. The parameters for the altitude and the speed of this mission were supposed to be a precise 115 miles from launch and with speeds topping out at 4,400 miles per hour. In reality the spacecraft carrying Ham reached an altitude of over 150 miles and speeds topping out at over 5,000 miles per hour. These couple of mishaps led to even more problems for Ham and his capsule during their return to Earth. Ham ended up landing over 130 miles from where he was predicted to land. He was extracted from the water by a helicopter before he could drown.[8] The capsule suffered a partial loss of pressure during the flight, but Ham's space suit prevented him from suffering any harm.[12]: 315 Ham's lever-pushing performance in space was only a fraction of a second slower than on Earth, demonstrating that tasks could be performed in space.[12]: 316

Ham's capsule splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean and was recovered by the USS Donner later that day.[12]: 316 His only physical injury was a bruised nose.[14] Ham however, did not seem to be troubled by his injury and appeared enthusiastic to be back home. He did become slightly agitated by all the press and pictures. This was because people at the time did not understand how hard missions like these are on the mind and body.[8] His flight was 16 minutes and 39 seconds long.[15] During this flight, Ham even experienced weightlessness for around six and a half minutes. He was able to fight through the extreme pressure of weightlessness, g force, and speed. Through all these challenges, Ham still had the ability to perform all his tasks correctly, and even to the similar standard he set on Earth. This was extremely promising news for the scientists observing Ham during the mission. The purpose of this mission was to see if humans would be able to be able to perform all the tasks that needed to be done while in space. By the end of the mission, it not only showed that humans can perform tasks nearly as well in space as on Earth, but that they also have a good chance of making it back home alive. They were able to see that even with all the mishaps that occurred with Ham and his flight he was still able to come home relatively safe. However, there still needed to be research on the long-term effects caused by time in space on the body.[13]

The results from his test flight led directly to Alan Shepard's May 5, 1961, suborbital flight aboard Freedom 7.[16]

Later life

Ham retired from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1963.[17] On April 5, 1963, Ham was transferred to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. where he lived for 17 years[7]: 255–257 before joining a small group of chimps at North Carolina Zoo on September 25, 1980.[18]

Ham suffered from chronic heart and liver disease.[17] On January 19, 1983, at age 26, Ham died.[19] After his death, Ham's body was given to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for necropsy. Following the necropsy, the plan was to have him stuffed and placed on display at the Smithsonian Institution, following Soviet precedent with pioneering space dogs Belka, and Strelka. However, this plan was abandoned after a negative public reaction.[20] Ham's skeleton is held in the collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Silver Spring, Maryland,[6] and the rest of Ham's remains were buried at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Colonel John Stapp gave the eulogy at the memorial service.[21]

Ham's backup, Minnie, was the only female chimpanzee trained for the Mercury program. After her role in the Mercury program ended, Minnie became part of an Air Force chimpanzee breeding program, producing nine offspring and helping to raise the offspring of several other members of the chimpanzee colony.[7]: 258–259 She was the last surviving Astro-chimpanzee and died at age 41 on March 14, 1998.[7]: 259

Cultural references

- Ray Allen & The Embers released the song "Ham the Space Monkey" in 1961.

- Tom Wolfe's 1979 book The Right Stuff depicts Ham's spaceflight,[22] as do its 1983 film and 2020 TV adaptations.

- The 2001 film Race to Space is a fictionalized version of Ham's story; the chimpanzee in the film is named "Mac".[23]

- In 2007, a French documentary made in association with Animal Planet, Ham—Astrochimp #65, tells the story of Ham as witnessed by Jeff, who took care of Ham until his departure from the Air Force base after the success of the mission. It is also known as Ham: A Chimp into Space / Ham, un chimpanzé dans l'espace.[24]

- The 2008 3D animated film Space Chimps follows anthropomorphic chimpanzees and their adventures in space. The primary protagonist is named Ham III, depicted as the grandson of Ham.[25]

- In 2008, Bark Hide and Horn, a folk-rock band from Portland, Oregon, released a song titled "Ham the Astrochimp", detailing the journey of Ham from his perspective.[26]

Use of chimpanzees in research

Research involving primates comprises only 0.3% of all non-human research, and chimpanzees comprise 5% of those subjects.[27] Chimpanzees are closely related to humans and are often used in research settings. Typically, chimpanzees are used for biomedical research. This includes research on infectious diseases to cognition or behavior.

Chimpanzees are very social animals, so relocating them to research facilities can be distressing. It is crucial that chimpanzees are allowed social interaction with other chimpanzees as well as other forms of enrichment. Without social interaction in the early stages of life, chimpanzees can experience issues with sexual and maternal behavior and social interactions with other chimpanzees raised in captivity with their mothers.[27]

Although chimpanzees are excellent subjects for research, they can pose some issues. They are unlike other highly used animals in research, like rodents, pigs, or dogs. They have incredible strength and intellect while being larger than typical research subjects. They cannot easily be restrained, so researchers have worked on getting chimpanzees to cooperate on their own terms.

Researchers implement three typical processes when using chimpanzees in research: habituation, desensitization, and positive reinforcement.[27] Habituation is used to decrease fears in the chimpanzees. For example, if the chimpanzee must be transported, their carrier may be left in their enclosure. This would allow the chimpanzee to acclimate to this new object and be more comfortable when transported. This can apply to all tools used in research, like cotton swabs or syringes. However, these are not left in their habitats due to safety reasons. If habituation did not reduce a chimpanzee's fearful reaction, desensitization would be used. This is primarily used for phobias. Instead of being only introduced to the object, the chimpanzee must elicit a desired response to the object perceived as threatening. The main goal of desensitization is changing a negative response to a neutral or positive reaction. Positive reinforcement is done to help solidify the actions or responses a chimpanzee gives. These processes help chimpanzees become comfortable around general research equipment and personnel.

Ethics of animal-based research on chimpanzees

Primates are well known for their high cognitive and emotional function. This is one reason some believe that scientific testing on primates is unethical. Primates have shown they have similar mental skills to humans, like problem-solving, math, and memory. Similarly, they experience emotions like happiness, sadness, and anxiety. Chimpanzees have even shown signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to scientific research.[28] One of the main concerns regarding ethics is the sourcing of primates. Most are stolen from the wild and sold. They are then shipped out to various locations. This transportation process is very stressful for the animal because of the small crates and lack of easy access to food and water. Studies have shown that it can take months for the animals' physiological systems to return to normal, and the research they undergo further stresses their bodies.[28] Most countries have banned chimpanzees from scientific research in Europe, and there is continuing pressure to end all use of primates.[28]

In the case of Ham, he was seen as a space hero. However, Ham faced many unethical situations. Ham was sold to the United States Air Force for $457 in 1959.[29] From there, Ham was assessed and trained for his space flight. One test Ham faced was that of decompression chambers which simulated pressure changes corresponding to altitude changes of 35,000 to 150,000 feet.[29] He was strapped into a seat that locked him in place with a metal loop around his neck daily. Before his flight, Ham had electrodes placed under the skin and an 8-inch rectal thermometer inserted.[29] Due to a valve malfunction, the Redstone rocket delivered thrust higher than intended.[30] The anomaly triggered the emergency escape rocket and subjected Ham to 17g's of acceleration.[30] The jettison of the spent escape rocket also caused the retro rocket pack to be prematurely jettisoned.[30] The lack of the retro rocket caused the capsule to reenter the atmosphere with excessive speed.[30] Ham was subjected to 14.7 g's during reentry.[30] The capsule was damaged during splashdown and settled deeper in the water than designed.[30] Ham experienced a vast number of other issues during and after his flight. He was chosen to fly because of his agreeable nature, but Ham was not the same after the flight. He would become agitated when the press approached him and panic when his handler would try to situate him for photos.[29] Some famous images show him smiling in his capsule, which would appear as though he was happy. Yet chimpanzees smile out of fear, not happiness.

See also

- Animals in space

- Monkeys and apes in space

- Albert II, a rhesus monkey who became the first mammal in space in June 1949

- Enos, the second of the two chimpanzees launched into space, and the only one to orbit Earth

- Laika, a Soviet space dog and the first animal to orbit Earth

- Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, orbited in April 1961

- Félicette, the only cat in space

- One Small Step: The Story of the Space Chimps, 2008 documentary

- Spaceflight

- List of individual apes

References

- "Chimp survives 420-mile ride into space". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. Associated Press. February 1, 1961. p. 1.

- "Chimp sent out on flight over Atlantic". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. UPI. January 31, 1961. p. 1.

- Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989). "This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury". NASA History Series. NASA Special Publication-4201. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Brown, Laura J. (November 13, 1997). "Obituary: NASA Medical director Hamilton 'Ham' Blackshear". Florida Today. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Gray, Tara (1998). "A Brief History of Animals in Space". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- Nicholls, Henry (February 7, 2011). "Cameroon's Gagarin: The Afterlife of Ham the Astrochimp".

- Burgess, Colin; Dubbs, Chris (January 24, 2007). Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer-Praxis Books in Space Exploration. ISBN 978-0-387-36053-9. OCLC 77256557.

- Hanser, Kathleen (November 10, 2015). "Mercury Primate Capsule and Ham the Astrochimp". airandspace.si.edu. Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- Haraway, Donna (1989). Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. New York: Routledge. p. 138.

- "Chop Chop Chang Commemorative Patch (HAM the Astrochimp)". Retrorocket Emblems. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- House, George (April–June 1991). "Project Mercury's First Passengers". Spacelog. 8 (2): 4–5. ISSN 1072-8171. OCLC 18058232.

- Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1966). This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury. NASA History Series. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 00569889. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- chimpadmin. "Ham, the First Chimpanzee in Space". Save the Chimps. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- Zackowitz, Margaret G. (October 2007). "The Primate Directive". National Geographic. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- "NASA Project Mercury Mission MR-2". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- Burgess, Colin (2014). "The Mercury flight of chimpanzee Ham" (PDF). Freedom 7. Springer. pp. 58–59. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-01156-1_2. ISBN 978-3-319-01155-4.

- Schierkolk, Andrea (July 2015). "HAM, A Space Pioneer". Military Medicine. 180 (7): 835 – via Oxford Academic.

- "Ham the astrochimp: hero or victim?". The Guardian. December 16, 2013.

- "Ham, First Chimp in Space, Dies in a Carolina Zoo at 26". The New York Times. January 20, 1983. ProQuest 122119079.

- Schierkolk, Andrea (July 2015). "HAM, A Space Pioneer". Military Medicine. 180 (7): 836. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00033. PMID 26126257.

- Roach, Mary (2010). Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void. Norton. pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-0393068474.

- Wolfe, Tom (March 4, 2008). The Right Stuff. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 178. ISBN 9781429961325.

- Foundas, Scott (March 14, 2002). "Race to Space". Variety. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Kerviel, Sylvie (July 13, 2007). "Ham, un chimpanzé dans l'espace". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Space Chimps at AllMovie

- For Melville, With Love Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, by Ezra Ace Caraeff, August 14, 2008, Portland Mercury

- Bloomsmith, Mollie A.; Schapiro, Steven J.; Strobert, Elizabeth A. (October 1, 2006). "Preparing Chimpanzees for Laboratory Research". ILAR. 47 (4): 316–325. doi:10.1093/ilar.47.4.316. PMID 16963812.

- CONLEE, KATHLEEN M., and ANDREW N. ROWAN. "The Case for Phasing Out Experiments on Primates." The Hastings Center Report 42, no. 6 (2012): S31–34. JSTOR 44159184.

- Gambone, Emily (January 31, 2022). "Why We Fight for Nonhuman Rights: Ham's Story". Nonhuman Rights Project.

- Burgess, Colin (2014). Burgess, Colin (ed.). Freedom 7: The Historic Flight of Alan B. Shepard, Jr. Springer Praxis Books. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 29–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-01156-1_2. ISBN 978-3-319-01156-1.

Further reading

- Farbman, Melinda; Gaillard, Frye (June 2000) [2000]. Spacechimp: NASA's Ape in Space. Countdown to Space. Berkeley Heights, New Jersey: Enslow Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7660-1478-7. OCLC 42080118. Brief biography of Ham, aimed at children ages 9–12.

- Rosenstein, Andrew (July 2008). Flyboy: The All-True Adventures of a NASA Space Chimp. Windham, Maine: Yellow Crane Press. ISBN 978-0-9758825-2-8. A novel about Ham and his trainer.

- Burgess, Colin; Dubbs, Chris (January 24, 2007). Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer-Praxis Books. ISBN 978-0-387-36053-9. Book covering the life and flight of Ham, plus other space animals.

External links

- Pictures from the NASA Life Sciences Data Archive

- Who2 profile: Ham the Chimp

- Animal Astronauts

- Chimp Ham: "Trailblazer In Space" 1961 Detroit News

- In Praise of Ham the Astrochimp Archived February 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine in LIFE