Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas (Punic: 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕𐤟𐤁𐤓𐤒, Ḥomilqart Baraq; c. 275–228 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair.

Hamilcar Barca | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 275 BC |

| Died | 228 BC (aged around 46–47) |

| Title | Carthaginian General |

| Term | 19 years; 247–228 BC |

| Successor | Hasdrubal the Fair |

| Children | Hannibal Hasdrubal Mago three daughters (names unknown) |

Hamilcar commanded the Carthaginian land forces in Sicily from 247 BC to 241 BC, during the latter stages of the First Punic War. He kept his army intact and led a successful guerrilla war against the Romans in Sicily. Hamilcar retired to Carthage after the peace treaty in 241 BC, following the defeat of Carthage. When the Mercenary War burst out in 239 BC, Hamilcar was recalled to command and was instrumental in concluding that conflict successfully. Hamilcar commanded the Carthaginian expedition to Spain in 237 BC, and for eight years expanded the territory of Carthage in Spain before dying in battle in 228 BC. He may have been responsible for creating the strategy which his son Hannibal implemented in the Second Punic War to bring the Roman Republic close to defeat.

Name

Hamilcar is the latinization of Hamílkas (Greek: Ἁμίλκας), the hellenized form of the common Semitic Phoenician-Carthaginian masculine given name ḤMLK (Punic: 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤊)[1][2] or ḤMLQRT (𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕), meaning "Melqart's brother".[1]

The cognomen or epithet BRQ (𐤁𐤓𐤒) means "thunderbolt" or "shining". It is cognate with the Arabic name Barq, Maltese word Berqa, the Assyrian Neo-Aramaic name Barkho, and the Hebrew name Barak and equivalent to the Greek Keraunos, which was borne by many commanders contemporary with Hamilcar and his son Hannibal.[3]

Early life

Little is known about the origins or history of the Barca family prior to the Punic Wars. Quoting Tony Bath, "The Barca family, which originally came from Cyrene, was a powerful one but not at that time among the first families of Carthage". (The origins of Carthage go back to the city of Tabarka, present-day Tunisia).[4] Unfortunately Tony Bath omits references. Lance Serge states that Hamilcar's family was part of the landed aristocracy of Carthage.[5] Hamilcar was a young man of 28 when he received the Sicilian command in 247 BC. By this time he had three daughters, and his son Hannibal was born during the same year.

Situation in Sicily

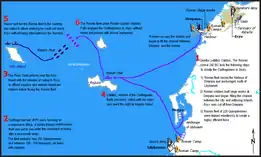

The war, which had started in 264 BC, continued after the Romans abandoned Africa; however, neither side gained a decisive advantage until 249 BC.[6] The Romans rebuilt their fleet after losing 364 ships in a storm in 255 BC, added 220 new ships, and captured Panormus (modern Palermo) in 254 BC;[7] however, 150 ships were lost in another storm in 253 BC.[8] The Romans had occupied most of Sicily by 249 BC and they besieged the last two Carthaginian strongholds – in the extreme west.[9] The situation changed when the surprise attack on the Carthaginian fleet met defeat at the Battle of Drepana[10] and the following Carthaginian victory at the Battle of Phintias; the Romans were all but swept from the sea.[11] It was to be seven years before Rome again attempted to field a substantial fleet.[12][13]

The Carthaginians had gained command of the sea after their victories in 249 BC, but they only held two cities in Sicily: Lilybaeum and Drepanum by the time Hamilcar took up command. The Carthaginian state was led by the landed aristocracy at the time, and they preferred to expand across northern Africa instead of pursuing an aggressive policy in Sicily. Hanno "The Great"[14] was in charge of operations in Africa since 248 BC and had conquered considerable territory by 241 BC.[15] Carthage did not take advantage of their naval supremacy and carry the war to Italy other than launching a few raids.

Carthage at this time was feeling the strain of the prolonged conflict. In addition to maintaining a fleet and soldiers in Sicily, they were also fighting the Libyans and Numidians in northern Africa.[16] As a result, Hamilcar was given a fairly small army and the Carthaginian fleet was gradually withdrawn; Carthage put most of its ships into reserve to save money and free up manpower,[12][13] so by 242 BC, Carthage had no ships to speak of in Sicily.[17]

Hamilcar in Sicily

The Carthaginian leadership probably thought Rome had been defeated and invested little manpower in Sicily.[18] With a small force and no money to hire new troops, Hamilcar's strategic goal probably was to maintain a stalemate, as he had neither the resources to win the war nor the authority to peacefully settle it.[19] Hamilcar was in command of a mercenary army composed of multiple nationalities and his ability to successfully lead this force demonstrates his skill as field commander. He employed combined arms tactics, like Alexander and Pyrrhus,[20] and his strategy was similar to the one employed by Fabius Maximus during the Second Punic War, ironically against Hannibal, Hamilcar's eldest son. The difference was that Fabius commanded a numerically superior army to his opponent, had no supply problems, and had room to manoeuvre, while Hamilcar was mostly static, had a far smaller army than the Romans and was dependent on seaborne supplies from Carthage.

Panormus 247 BC – 244 BC

Hamilcar, upon taking command in the summer of 247 BC,[21] punished the rebellious mercenaries (who had revolted because of overdue payments) by murdering some of them at night and drowning the rest at sea,[22] and dismissing many to different parts of northern Africa. With a reduced army and fleet, Hamilcar commenced his operations.[23] The Romans had divided their forces: Consul Lucius Caelius Metellus was near Lilybaeum, while Numerius Fabius Buteo was besieging Drepanum at that time. Hamilcar probably fought an inconclusive battle at Drepanum,[22] but there is cause to doubt this.[24]

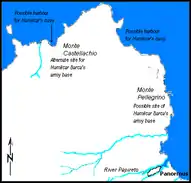

Hamilcar next raided Locri in Bruttium and the area around Brindisi in 247 BC.[25] On his return he seized a strong position on Mount Ercte (Monte Pellegrino, just north of Palermo or Mt. Castellacio, 7 miles north-west of Palermo),[26] and not only maintained himself against all attacks, but carried on with his seaborne raids ranging from Catana[27] in Sicily to as far as Cumae in central Italy.[28][29] He also set about improving the spirit of the army, and succeeded in creating a highly disciplined and versatile force. While Hamilcar won no large-scale battle or recaptured any cities lost to the Romans, he waged a relentless campaign against the enemy, and caused a constant drain on Roman resources. However, if Hamilcar had hoped to recapture Panormus, he failed in his strategy. Roman forces led by the consuls Manius Otacilius Crassus and Marcus Fabius Licinus achieved little against Hamilcar in 246 BC, and the consuls of 245 BC, Marcus Fabius Bueto and Atilius Bulbus, fared no better.

Eryx 244 BC – 241 BC

In 244 BC, Hamilcar transferred his army at night by sea[30] to a similar position on the slopes of Mt. Eryx (Monte San Giuliano),[31] from which he was able to lend support to the besieged garrison in the neighbouring town of Drepanum (Trapani).[28] Hamilcar seized the town of Eryx, captured by the Romans in 249 BC, after destroying the Roman garrison, and positioned his army between the Roman forces stationed at the summit and their camp at the base of the mountain.[32] He removed the population to Drepana.[30] Hamilcar continued his activities unhindered from his position for another two years, being supplied by road from Drepana,[33] although Carthaginian ships had been withdrawn from Sicily by this time and no naval raids were launched.[17] During one of the raids, when troops under a subordinate commander named Bodostor engaged in plunder against the orders of Hamilcar and suffered severe casualties when the Romans caught up to them, Hamilcar requested a truce to bury his dead. Roman consul Fundanius (243/2 BC) arrogantly replied that Hamilcar should request a truce to save his living and denied the request.[34] Hamilcar managed to inflict severe casualties on the Romans soon after, and when the Roman consul requested a truce to bury his dead, Hamilcar replied that his quarrel was with the living only and the dead had already settled their dues, and granted the truce.[35]

The actions of Hamilcar, and his immunity to defeat, plus the stalemate at the siege of Lilybaeum caused the Romans to start building a fleet in 243 BC to seek a decision at sea. However, the constant skirmishing without ultimate victory may have caused the morale of some of Hamilcar's troops to crack and 1,000 Celtic mercenaries tried to betray the Punic camp to the Romans, which was foiled.[36] Hamilcar had to promise considerable rewards to keep the morale of his army up, which was to produce near fatal problems for Carthage later on.

Roman response: privately funded fleet

The Roman Republic was nearly bankrupt and had to borrow money from wealthy citizens to fund the construction of a fleet of 200 quinqueremes, which blockaded Carthaginian positions in Sicily in 242 BC by seizing the harbour of Drepana and anchorages at Lilybaeum, while Roman soldiers built siege works around Drepanum.[37] The better-trained Roman fleet[38] defeated a hastily raised, undermanned and ill-trained Punic fleet at battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BC, cutting Sicily off from Carthage. Carthaginian leadership requested terms to the victorious Roman commander, Gaius Lutatius Catulus and authorised Hamilcar Barca to open negotiations, probably to avoid the responsibility of the defeat. Hamilcar in turn nominated Gisco,[39] the Carthaginian commander of Lilybaeum, to conduct the talks. Carthage often hauled defeated generals and admirals before the Tribunal of 100 and had them crucified, so Hamilcar probably distanced himself from the possibility of prosecution if the Roman terms turned out to be harsh enough for Carthaginian authorities to seek a scapegoat.[40]

Peace of Lutatius terms of the treaty

This treaty replaced all previous treaties between the two powers. The initial conditions laid out by Lutatius to Gisco were:[41]

- The Carthaginians will evacuate all Sicily.

- Carthage should not make war on Syracuse and their allies.

- Carthage would pay Rome 2,200 Euboean silver talents (56 tons) over a 20-year period as reparations.

- The Carthaginian army would surrender their weapons and all Roman deserters immediately.

Hamilcar Barca refused the demand to surrender Roman deserters or disarm Carthaginian soldiers, despite being threatened by Lutatius to have the Punic army pass under the yoke.[42] Lutatius did not press the issue further, and the Carthaginian soldiers were later allowed to leave Sicily under arms with their honor intact,[43] and without any token of submission – a rare gesture granted by the Romans to a defeated enemy. Roman deserters may have been surrendered on a later date.[44]

Lutatius did not have the authority to ratify the agreement he made with Hamilcar, so he forwarded them to the Comitia Centuriata in Rome. The Romans rejected these terms and appointed ten commissioners, led by Quantius Lutatius Cerco, brother of the consul and himself consul in 240 BC, to reexamine the conditions.[45] They added some conditions and amended some of the ones given by Lutatius:[46]

- Carthage would evacuate all islands between Italy and Sicily – probably the Aegates Islands in addition to the Aeolian Islands. This meant Roman acknowledgement of Carthaginian control over Malta, Pantelleria, Sardinia and Corsica.

- Carthage would pay 2,200 silver talents in 10 year installments, and 1,000 talents immediately; a total of 3,200 talents as war reparations.

- Carthage will ransom all Punic prisoners, while all Roman prisoners would be freed without payment of ransom.[47]

- Carthaginian warships were forbidden to sail along Italian shores or those of their allies.[44]

- Neither side should make war on the other's allies, or seek to change their allegiance by allying with them directly or interfering with their internal affairs. Neither side would seek to recruit soldiers, levy tribute or build public buildings on the other power's territories.[48]

The last condition is mentioned by Polybius in place of the one regarding not making war on Syracuse. It is possible that Hamilcar Barca secured the last clause after the initial conditions, which were more favorable to Carthage, was altered by Rome with a harsher one. Hamilcar Barca gathered the Carthaginian soldiers from Drepana and Eryx at Lilybaeum, surrendered his command,[49] returned to Carthage and retired to private life, leaving Gisco and the Carthaginian government to pay off his soldiers. Whatever was the motivation behind this act, it was resented by the mercenaries left behind in Sicily.

Truceless War

The "Undefeated" army now created a unique problem for Carthage. Had Hamilcar suffered a decisive defeat, casualties and prisoners would have diminished their numbers and Carthage would have had an excuse not to pay anything. But now the 20,000 man army had to be paid their full due.

Gisco sensibly sent the troops to Carthage in small groups with intervals in between[50] so the government could pay them off without trouble. However, the Carthaginian authorities waited until the whole army had gathered at Carthage, probably by the summer of 241 BC. As the strain on the Punic population increased, Carthaginian authorities then sent them off to Sicca, planning to plead with the whole army to forgo their unpaid wages by pointing out the dire financial situation of Carthage.[51] Hamilcar's former soldiers, who had been kept together only by his personal authority and by the promise of good pay, broke out into open mutiny[28] once Hanno the Great tried to impose this, and marched on Carthage and encamped at Tunis. The soldiers refused to accept Hamilcar as an arbitrator, angered by his refusal to accompany his army from Sicily and retiring to Carthage as soon as the treaty with Rome was formalized, and although Carthage at this point conceded to all their demands, things soon boiled over and started the conflict known as the Mercenary War. The rebels, under Spendius and Matho, were joined by 70,000 African subjects of Carthage.[52] The rebels divided their forces: detachments were sent to besiege Utica and Hippo, while others cut Carthage off from the mainland, probably in the winter of 241 BC or spring of 240 BC.

Hamilcar recalled

Hanno the Great was given command of the Punic army, which was raised from Carthaginian citizens and mercenaries recruited from abroad, plus cavalry squadrons and 100 elephants. Hanno sailed to Utica in the spring of 241 BC, obtained siege equipment from the city and overran the rebel camp, the rebels fleeing before the charging Punic elephants. Hanno, accustomed to fighting Libyans and Numidians, did not anticipate any further trouble and left his army for Utica. However, the rebels regrouped, and observing lax discipline among the Punic troops, launched a surprise sortie and routed the Punic army while Hanno was absent,[53] driving the survivors to Utica and capturing all the baggage. Hanno marshaled his soldiers, but twice failed to engage the rebels under favorable conditions and twice failed to surprise them on other occasions. The Carthaginian government then raised an army of 10,000 soldiers and 70 elephants and put Hamilcar Barca in command. This army was small for leading a sortie against the stronger rebel forces, especially to lead into a pitched battle. The Carthaginians needed to gain the far side of the Bagradas, so they could manoeuvre freely, but lacked the strength to force a crossing against the superior rebel force guarding against this.[54] Hanno posted his army near Hippo Acra, where Matho's army was besieging the town.[55]

Battle of Macar River

The rebels held the hills to the west of Carthage and the only bridge across the Bagradas river leading to Utica.[56] Hamilcar observed that wind blowing from a certain direction uncovered a sandbar at the river mouth that was fordable and, under cover of night, the Punic army left Carthage and crossed the river. Hamilcar aimed to attack the small rebel band holding the bridge, but Spendius led the rebel force besieging Utica to confront Hamilcar. The Carthaginian army was caught in a pincer movement; Hamilcar pretended to retreat, and Spendius likely attempted to trap the outnumbered Carthaginians against the river with his two forces, pinning them with one and out-flanking them with the other. When his troops rushed towards the retreating Carthaginians, Spendius was either unable to control them or believed that the Carthaginians were fleeing and encouraged his forces' pursuit.[57] Hamilcar had managed to train his new recruits in some drill and basic battlefield maneuvers before they left Carthage.[58] As the two rebel forces came into clear sight the Carthaginians wheeled, and marched away. The Carthaginians were marching in good order so they could perform a pre-planned manoeuvre which they had practiced in Carthage, but the rebels, many of whom were inexperienced soldiers, believed that the Carthaginians were running away. Shouting encouragement to each other they broke into a run to pursue.[59] Hamilcar unleashed his trap as the disorderly rebels closed on his formation. As the cavalry and then the elephants came closer to the infantry Hamilcar ordered each in turn to also wheel about to face the rebels.[60] The modern historian Dexter Hoyos stresses that "[s]uch manoeuvres were about the simplest that any army could learn, once it mastered the absolute basics of marching in formation".[60]

It is not exactly known how Hamilcar managed to outwit the rebels. According to one line of thought,[61] the Carthaginian army order of march had the War Elephants leading the column, with the light troops and cavalry behind the elephants. Heavy infantry formed the rearguard, and the whole army marched in a single file in battle formation.[61]

According to another line of thought,[62] Hamilcar’s army marched in three separate columns, with the war elephants placed nearest the rebel army. The cavalry and light infantry were in the middle, while the heavy infantry was posted furthest from the rebel army.[62]

Through brilliant maneuvering, Hamilcar inflicted a heavy defeat on the rebel forces, leading to the killing of 8,000 mercenaries and the capturing of 2,000 men.[63] Hamilcar occupied the bridge, then established control over the surrounding region. Some of the surviving rebels fled towards Utica; others, after being driven from their camp near the bridge, fled to Tunis.

Hamilcar trapped

Hamilcar's victory opened communication with Utica, and gave Hamilcar the chance to bring nearby towns under Carthaginian control by force or negotiations. He made no attempt to join Hanno near Utica. Spendius rallied his forces, was reinforced by a detachment largely made of Gauls under Autaritus and shadowed Hamilcar as he advanced south east, keeping to the high ground to avoid Carthaginian elephants and cavalry and harassing their enemy at every possible opportunity. These "Fabian tactics" continued until Hamilcar encamped in a valley, probably near Nepheris, and the rebels trapped his army, with the Libyans blocking the exit, Spendius and his troops camping near the Punic army and the Numidians covering Hamilcar's rear. Hamilcar's army was saved by pure luck – a Numidian chieftain, Naravas, who would later marry Hamilcar's third daughter, defected with 2,000 horsemen. Hamilcar exited the valley and, after a hard-fought battle, defeated the army of Spendius. The rebel loss was 8,000 dead with 4,000 captured. Hamilcar offered the prisoners a choice – to join his army, or leave Africa with the condition never to take up arms against Carthage. The new joiners were armed with equipment captured from the rebels. By winter of 240 BC, the situation had improved for Carthage.

Beginning of atrocities

Rebel leaders feared mass desertions might result because of Hamilcar's policy towards prisoners. To forestall any such event, rebels committed an act of cruelty unpardonable by Carthage. Autaritus spread the rumor that Carthaginian prisoners led by Gisco were plotting to escape. Rebels opposing this were stoned and Gisco and his fellow prisoners were tortured to death. Autaritus announced that he would do the same with all Punic prisoners that fell into rebel hands in future. Hamilcar killed his prisoners and announced a policy of equal measure toward future rebel prisoners, thus ending any chance of desertion from the rebel army and the truceless war began in earnest.

Triple trouble and revival

Carthage was hit by a series of disasters in 239 BC: her fleet and supply flotilla bringing supplies from Empoia was sunk in a storm, the mercenaries in Sardinia rebelled and the cities of Utica and Hippo Acra killed their Punic garrisons and defected to the rebels. Carthage sent an expedition to Sardinia under Hanno, but this force killed their officers and joined the rebels. Furthermore, Hamilcar had invited Hanno the Great to join forces and try to end the rebellion as quickly as possible, but the generals failed to cooperate.

The gloomy situation changed when first Syracuse and then Rome came to the aid of Carthage. Syracuse redoubled the volume of supplies sent to Carthage. Rome forbade Italian traders to trade with rebels and encouraged trade with Carthage, freed Punic prisoners without ransom, and allowed Carthage to recruit mercenaries from Roman territories and flatly refused the invitation from Utica, Hippo and Sardinia to occupy these areas. Finally, when the Carthaginian Senate was unable to decide between Hamilcar and Hanno, the people's assembly left it to the army to decide on their Commander in Chief, and Hamilcar Barca was elected to sole command.[64] The people's assembly chose Hannibal of Paropos, son of another Hamilcar and a veteran of the First Punic War as Hamilcar's deputy.

Carthage blockaded

While Carthage was busy settling state affairs, Spendius and Matho decided to blockade the city from the landward side. However, as the rebels had no navy, Carthage could draw supplies from the sea and so did not face the threat of starvation. But the rebels would sally out from their camp at Tunis and approach the city walls to cause terror inside the city.[65] In response, Hamilcar began to harass the rebel supply lines and soon the rebels were placed in a state of siege. Spendius and Matho were joined by a force commanded by a Libyan chief named Zarzas, and the 50,000 strong army under Spendius moved away from Carthage.[66] Using tactics later made famous by Q. Fabius against Hannibal, Hamilcar's eldest son, the rebels shadowed Hamilcar's army, while moving south, harassing his soldiers and keeping to the high ground to avoid Carthaginian elephants and cavalry. After weeks of maneuvering, Hamilcar finally managed to trap about 40,000 rebels in a valley surrounded on three sides by mountains.[67]

The Gorge of the Saw

The exact location of this valley has never been conclusively identified. It was probably some distance from Carthage because, while Hamilcar blockaded the valley exits and waited for the rebels to starve, Matho's army at Tunis did not intervene although the trapped rebels held out awaiting his arrival. After the trapped rebels ran out of food, pack animals and cavalry horses and finally resorted to cannibalism, Spendius, Autaritus and Zarzas, accompanied by seven others, went to Hamilcar's camp to seek terms. Hamilcar offered to allow all the rebels to depart freely with a single garment, but retained the right to detain 10 persons. When the rebel leaders agreed to the terms, Hamilcar detained the rebel delegation. Deprived of leadership, and unaware of the pact, the mercenaries suspected treachery; the Libyans were the first to attack Hamilcar's positions.[68] The rebel army was slaughtered, with the elephants trampling most to death.

Setback in Tunis

Hamilcar next moved to confront the army of Matho at Tunis. He divided his army: Hannibal took half of the soldiers and camped to the north of Tunis, while Hamilcar camped to the south, thus hemming in Matho's army in Tunis. Hamilcar crucified Spendius and other rebel hostages outside Tunis to terrorize Matho, but this backfired when the rebels were able to surprise and defeat Hannibal's army due to their lax discipline. Punic survivors fled, and all their baggage was captured along with Hannibal and thirty Carthaginian senators.[69] Hamilcar retreated north near the mouth of the Bagradas River, while Matho crucified his prisoners on the same crosses Hamilcar had used to crucify the rebel leaders, then retreated out of Tunis and moved south.

At this point, the Carthaginian senate reinstated Hanno and forced Hamilcar to share command.[70] The Punic generals pursued Matho's army and won several small-scale engagements. After mustering their forces, a decisive battle was fought probably near the town of Leptis Minor. The Carthaginians destroyed the rebel army, after which the Libyan towns submitted to Carthage. When Utica and Hippo Acra held out, Hanno and Hamilcar besieged them, eventually receiving their surrender on terms. By the winter of 238 BC, the Mercenary revolt was over. Hanno and Hamilcar unleashed reprisals against the Numidian tribes that had sided with the rebels,[71] and the generals probably extended Carthaginian territory in Africa at the same time.[72] Carthage now began to fit out an expedition to recover Sardinia, with Hamilcar commanding Punic forces.

Sardinia

Punic Mercenaries stationed in Sardinia had rebelled in 239 BC, besieged Boaster and all Carthaginians in a citadel and later executed them after the fort fell. They managed to take over all Punic territories in Sardinia. Carthage sent a mercenary force under Hanno to retake the island in 239 BC, but this group also rebelled, killing Hanno and their Carthaginian officers and joining the rebels in Sardinia. The rebels requested Rome to take over Sardinia, which was turned down. Their heavy handedness with Sardinian natives caused native Sardinians to attack and expel the mercenaries by 237 BC. The expelled mercenaries took refuge in Italy and again requested Rome to take over Sardinia.

Rome, which had dealt with Carthage with all due honor and courtesy during the crisis, going as far as to release all Punic prisoners without ransom and refuse to accept offers from Utica and Rebels mercenaries based in Sardinia to incorporate these territories into the Roman domain, seized Sardinia and Corsica and forced Carthage to pay 1,200 talents for her initial refusal to renounce her claim over the islands.[73] This probably dealt a fatal blow to any chance of permanent peace between Rome and Carthage[74] and is one of the causes of the Second Punic War and held as the motivation of the subsequent military and political activities of Hamilcar.[75]

Punic politics

The aristocratic party had dominated Carthaginian politics since 248 BC. Hanno the Great was aligned with them and they espoused peaceful relations with Rome, even at the cost of abandoning overseas territories. Their choice to minimize the Sicilian operations while Hamilcar was in command, reduce the navy and support Hanno the Great's conquests in Africa, all of which were causes for the ultimate defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War. They had remained in power throughout the Mercenary War and had advocated Hanno's position over Hamilcar's more than once.

Their opponents probably had the support of people who had wanted to continue the war even after the defeat at Aegates Island.[76] The Mercantile Class, whose interests were hurt by the war, and would be marginalized by the abandonment of overseas operations, also supported this faction. People disenfranchised by the ruin of the navy and disruption of trade might have thrown in their lot with this group[77] and eventually Hasdrubal the Fair emerged as the leader. Hamilcar, furious that Sicily had been given up too soon, while he had been undefeated,[78] could rely on support from this party.

There is no clear record of the political activity in Carthage at this time. The political clout of the incumbent leaders was probably weakened by the defeat in the First Punic War, their mismanagement of the Mercenary troops and finally the Sardinia Affair. In an effort to reestablish their position, they decided to make a scapegoat of Hamilcar Barca.

Hamilcar supreme in Carthage

Hamilcar Barca was blamed by the Carthaginian Leaders for causing the Mercenary War by making unrealistic promises to his soldiers, especially the Celts, during his command in Sicily.[79] This event may have taken place as early as 241 BC or more likely in 237 BC.[80] The influence Hamilcar enjoyed among the people and the opposition party enabled him to avoid standing trial. Furthermore, Hamilcar allied with Hasdrubal the Fair,[81] his future son in law, to restrict the power of the aristocracy, which was led by Hanno the Great,[82] as well as gain immunity from prosecution. Hamilcar's faction gained enough clout, if not supreme power in Carthage, for Hamilcar to implement his next agenda. Hamilcar's first priority, probably, was to ensure that the war indemnity was paid regularly so the Romans had no excuse to interfere in Carthaginian affairs. His second was to implement his strategy for preparing Carthage for any future conflict with Rome,[83] or enable Carthage to defend itself against any aggression.[84]

Operations in North Africa

Hamilcar obtained permission from the Carthaginian Senate for recruiting and training a new army, with the immediate goal of securing the African domain of Carthage. As this was in line with the goal of the "Peace Party" of Hanno the Great, probably no serious opposition was offered. Training for the army was obtained in some Numidian forays, then Hamilcar marched the army westwards to the Pillars of Hercules. Hasdrubal the Fair commanded the fleet[85] carrying supplies and elephants along the coast, keeping pace with the army.

Hamilcar, on his own responsibility and without the consent of the Carthaginian government,[86] ferried the army across to Gades to start an expedition into Hispania (236 BC), where he hoped to gain a new empire to compensate Carthage for the loss of Sicily and Sardinia.[28] Iberia would also serve as a base for any future conflicts against the Romans which would be independent of political interference from Carthage, and the campaigns would enhance the reputation of Hamilcar Barca.[87] Hamilcar's political clout in Carthage may have been enough to stifle any opposition in Carthage against his Iberian venture,[88] or he did face stiff opposition and had used the booty from his Iberian campaigns to buy his way out. Whatever the case, Hamilcar enjoyed uninterrupted command in Iberia during his stay there.

Barcid Spain

Hamilcar's army either crossed the Straits of Gibraltar into Iberia from West Africa[89] or, having returned to Carthage after the African activities, sailed along the African coast to Gades.[90] Hasdrubal the Fair and Hannibal, then a child of nine, accompanied Hamilcar; it is not known who led Hamilcar's supporters in Carthage in the absence of Hamilcar and Hasdrubal. Prior to his departure from Carthage, Hamilcar made sacrifices to obtain favorable omens and Hannibal swore never to be a "Friend of Rome" and "Never to show goodwill to the Romans".[91] Several modern historians have interpreted this as Hannibal swearing to be a lifelong enemy of Rome bent on revenge,[92][93][94][95] while others hold that this interpretation is a distortion.[96][97][98]

Iberian political situation

Hamilcar probably landed at Gades in the summer of 237 BC. Whatever direct territorial control Carthage had had in the past in Iberia,[99] this had been mostly lost by this time as Hamilcar was "re-establishing Carthaginian authority in Iberia".[89] Phoenician colonies were strung along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of southwestern Spain and exercised some degree of control over their immediate areas, but only had trading contacts, not direct control, over the tribes of Iberia at that time.[100] Iberian and Celtiberian tribes were not under any unified leadership at this time and were warlike, although some had absorbed varying degrees of Greek and Punic cultural influence.

Ancient rivals: Punics and Phocaeans

Carthage's failure to prevent the establishment of Massalia[101] by Phocaean Greeks in 600 BC had created a rival that eventually came to dominate trade in Gaul and to plant colonies in Catalonia, at Mainke near Málaga,[102] three colonies near the mouth of Sucro, and at Alalia in Corsica. Greek piracy had forced Carthage to team up with the Etruscans to drive the Greeks from Corsica, and destroy the colony at Mainke in Iberia. By 490 BC, Massalia had managed to defeat Carthage twice, and a boundary along Cape Nao in Iberia was agreed upon,[103] while Carthage had closed the Straits of Gibraltar to foreign shipping. Massalia had become friendly with Rome over the years, if not an outright ally by 237 BC, and this connection would become a significant factor in the power politics of the region.

Securing the silver supply

Hamilcar's immediate objective was to secure access to the gold and silver mines of Sierra Morena, either by direct and indirect control.[104] Negotiations with the "Tartessian" tribes were successfully concluded, but Hamilcar faced hostility from the Turdetani or Turduli tribe, near the foothills of modern Seville and Córdoba. The Iberians had support from Celtiberian tribes and were under the command of two chieftains, Istolatios and his brother. Hamilcar defeated the confederates, killed the leaders and several of their soldiers, while he released a number of prisoners and incorporated 3,000 of the enemy into his army. The Turdetani surrendered.[105] Hamilcar then fought a 50,000 strong army under a chieftain named Indortes. The Iberian army fled before the battle was joined. Hamilcar besieged Indortes, tortured and crucified him after his surrender but allowed 10,000 of the captured enemy soldiers to go home.[106]

Having secured control over the mines, and the river routes of Guadalquivir and Guadalete giving access to the mining area, Gades began to mint silver coins from 237 BC. Carthaginians may have taken control of the mining operations and introduced new technologies to increase production.[107] Hamilcar now had the means to pay for his mercenary army and also to ship silver ore to Carthage to help pay off the war indemnity. Hamilcar was in a secure enough position in Iberia to send Hasdrubal the Fair with an army to Africa to quell a Numidian rebellion in 236 BC. Hasdrubal defeated the rebels, killing 8,000 and taking 2,000 prisoners before returning to Iberia.

Expanding eastward 235 BC – 231 BC

Hamilcar, after subduing Turdetania[108] next moved east from Gades towards Cape Nao. He met fierce resistance from the Iberia tribes, even the friendly Bastetani offered battle. Four years of constant campaigns, details of which are not known, saw Hamilcar subdue the area between Gades and Cape Nao. In the process, Hamilcar created a professional army of Iberians, Africans, Numidians and other mercenaries that Hasdrubal the Fair would inherit and Hannibal would later lead across the Alps to immortality. By 231 BC, Hamilcar Barca had consolidated his Iberian territorial gains and established the city of Akra Leuke (Alicante),[109][110] probably in 235 BC, to guard Punic holdings, and possibly took over the area of Massalian colonies near the mouth of Sucro River.[111] Massalia, probably alarmed by the Carthaginian advance towards their area of influence, mentioned this expansion to the Romans, who decided to investigate the matter.

Rome takes a look

While Hamilcar campaigned in Iberia, Rome was entangled in Sardinia, Corsica and Liguria, where the natives had put up stiff resistance against Roman occupation – campaigns had been fought in these areas between 236 – 231 BC to retain and expand Roman dominion. Rome suspected Carthage of aiding the natives, and had sent embassies to Carthage in 236, 235, 233 and 230 BC to accuse and threaten the Punic state. Nothing had come of these supposed episodes and some scholars doubt their authenticity. In 231 BC, a Roman embassy visited Hamilcar in Spain to inquire about his activities. Hamilcar simply replied that he was fighting to gather enough booty to pay off the war indemnity.[112] The Romans withdrew and did not bother the Carthaginians in Spain until 226 BC.

Final campaigns 231 BC – 228 BC

After the establishment of Akra Leuke, Hamilcar began to move northwest but no records of his campaigns exist. Hamilcar had split his forces in the winter of 228 BC, Hasdrubal the Fair was sent on a separate campaign, while Hamilcar besieged an Iberian town, then sent the bulk of his troops to winter quarters at Akra Leuke. Hamilcar's sons, Hannibal and Hasdrubal, had accompanied him. The town, called Helike, is commonly identified with Elche, but given that it is situated close to Hamilcar's base at Akra Leuke from which he could readily draw reinforcement, it cannot be the place where the following events unfolded.[113] It is possible that Hamilcar died battling the Vettoni, who lived across the Tagus west of Toledo and to the north of Turduli and northwest of Oretani territory.[114]

Death of Hamilcar

Orissus, chieftain of the Oretani tribe, came to the assistance of the besieged town. There are several versions to what happened next: Orissus offered to aid Hamilcar, then attacked the Punic army, and Hamilcar drowned during a retreat across the Jucar river;[115] the Oretani sent ox-driven carts to the Carthaginian position, then set them on fire and Hamilcar died in the resulting melee;[116] Hamilcar accepted an offer to parley, then led the enemy in one direction while Hannibal and Hasdrubal Barca fled in the opposite direction. According to Appian, Hamilcar was thrown from his horse and drowned in a river,[117] but Polybius says he fell in battle in an unknown corner of Iberia against an unnamed tribe.[118]

In eight years, Hamilcar had secured an extensive territory in Hispania by force of arms and diplomacy, but his premature death in battle (228 BC) denied Carthage a complete conquest. Legend tells that he founded the port of Barcino (deriving its name from the Barca family), which was later adopted and used by the Roman Empire and is, today, the city of Barcelona.[119] Despite the similarities between the name of the Barcid family and that of the modern city, it is usually accepted that the origin of the name "Barcelona" is the Iberian Barkeno.[120]

Family

Hamilcar had at least three daughters and at least three sons.

His first daughter was married to Bomilcar, who was a suffete of Carthage and may have commanded the Punic fleet in the Second Punic war. His grandson, Hanno, was an important commander in the army of his son Hannibal.

The second daughter was married to Hasdrubal the Fair.

His third daughter married the Berber ally Naravas,[121] a Numidian chieftain whose defection had saved Hamilcar and his army during the mercenary war.

Hamilcar had three sons, Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago, who were all to have distinguished military careers. An unnamed fourth son is often referred to, but details are lacking.

Hamilcar's legacy: The Grand Strategy

Hamilcar stood out far above the Carthaginians of his age in military and diplomatic skill and in strength of patriotism; in these qualities he was surpassed only by his son Hannibal, whom he may have imbued with his own deep suspicion of Rome and trained to be his successor in the conflict. One historian commented that had he not been the father of Hannibal, Hamilcar's Sicilian front might have received scant notice.[122] Hamilcar is thought to be the best commander of the First Punic War and as a man, Cato placed Hamilcar a cut above most leaders, including most Romans.[123] By the power of his personal influence among the mercenaries and the surrounding African peoples, superior strategy and some luck,[28] as well as cooperation, if unenthusiastic, from Hanno the Great, Hamilcar crushed the revolt by 237 BC amid a war marked with cruel atrocities from both sides.[124]

Enemy of Rome

The milder terms Rome had given to Carthage in the aftermath of the First Punic War, and the friendly conduct of Rome during the mercenary war might have raised the possibility of a long period of peace between the two powers, but the seizure of Sardinia destroyed any real chance of peace among equals. According to Polybius, the causes of the Second Punic war were as follows:

- Hamilcar felt that Carthage had given up on Sicily too soon in the First Punic War. Hamilcar had been undefeated and was forced to make peace. The subsequent Mercenary War showed that Carthage was capable of further military effort.

- Roman occupation of Sardinia, and then Corsica, indicated the untrustworthiness of Romans and their willingness to meddle when they saw fit regardless of treaties between the powers. This is the second and most important cause of the Second Punic War.[75] This had aroused resentment among many Punic citizens, and Carthage had no hope of resisting Rome at their weakened condition.

- The success of Hamilcar and his family in Spain, which rebuilt Carthaginian finances and created a standing army, giving Carthage the means to resist Rome.

Based on this, and Hannibal's oath, some historians infer that Hamilcar's post-Mercenary War activities were aimed at eventual war with Rome, which was inherited by his sons, and some further suggested that Hamilcar devised the strategy of invading Italy by crossing the Alps as well as Hannibal's battle tactics.[122] Without Punic records to cross reference, these remain mere supposition.

Hamilcar in literature

- Salammbô, by Gustave Flaubert

- Pride of Carthage, by David Anthony Durham

- "Hamilcar Barca," a poem by Roger Casement

See also

- Barcids, Hamilcar's dynasty

- Battle of the Bagradas

References

Citations

- Geus (1994), s.v. "Hamilcar".

- Huss (1985), p. 565.

- S. Lancel, Hannibal p. 6.

- Bath, Tony, Hannibal's Campaigns, p. 18 ISBN 0-88029-817-0

- Lancel, Serge, Hannibal, p. 8 ISBN 0-631-21848-3

- Scullard 2006, p. 559.

- Bagnall 2005, p. 80.

- Miles 2011, pp. 189–190.

- Miles 2011, p. 190.

- Goldsworthy 2003, pp. 117–121.

- Bagnall 2005, pp. 88–91.

- Goldsworthy 2003, pp. 121–122.

- Rankov 2015, p. 163.

- Appian Hispania 4

- Diodorus Siculus 24.10, Polybius 1.73.1, 1.72.3

- Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars, pp. 92–94 ISBN 0-312-34214-4

- Polybius 1.59.9

- Lazenby, J.F, First Punic War, p. 144

- Miles, Richard, Carthage Must be Destroyed, p. 193, ISBN 978-0-141-01809-6

- Baker, G.P, Hannibal, p. 54 ISBN 0-312-34214-4

- Polybius 1.56.2

- Zonaras 8.16

- Lazenby, John F., First Punic War, p. 145 ISBN 1-85728-136-5

- Lazenby, John .F, ‘’First Punic War’’, p. 146

- Polybius 1.56.3

- Lazenby, John F., First Punic War, p. 147 ISBN 1-85728-136-5

- Diodorus Siculus 24.10

- Caspari 1911, p. 877.

- Polybius, 1.56.9–10

- Diodorus Siculus 24.8

- Lazenby, John F., ‘’First Punic War’’, p. 148 ISBN 1-85728-136-5

- Polybius 1.58.2

- Polybius 1.58.3

- Diodorus Siculus 24.9.1–3

- Lazenby, J.F, The First Punic War, p. 149 ISBN 0-312-34214-4

- Polybius 2.7.6–11, Zonaras 8.16

- Polybius 1.59.9–10

- Polybius 1.59.9–12

- Diodorus Siculus 24.13, Polybius 1.66.1

- Lazenby, John F. The First Punic War, p. 157

- Polybius 1.62.8–9

- Diodorus Siculus 24.13, Cornelius Nepos, Hamilcar, 1.5

- Polybius, 1.20.6–14

- Zonaras 8.17

- Valerius Maximus 1.3.1

- Polybius 1.63.3

- Eutropius 2.27.4

- Polybius 3.27.2–3

- Polybius 1.66.1, 68.12, Zonaras 8.17

- Polybius 1.66.2–4

- Polybius 1.66.5

- Polybius 1.70.7–9

- Polybius 1.74.9

- Hoyos 2007, pp. 111–112.

- Polybius 1.73.1, 75.2

- Polybius 1.75.5

- Hoyos 2007, p. 122.

- Hoyos 2007, p. 116.

- Hoyos 2007, pp. 118, 117–118, 122–123.

- Hoyos 2007, p. 123.

- Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars, pp. 116–117

- Dodge, T.A, Hannibal, p. 135

- Polybius 1.76.4–5

- Polybius 1.82.5

- Polybius 1.73.7

- Polybius 1.84.3

- Polybius 1.85.7

- Polybius 1.85.6

- Polybius 1.86.7

- Polybius 1.87.3

- Diodorus Siculus 24.33

- Cornelius Nepos, Hamilcar 2.5

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage, pp. 135–136 ISBN 1-85728-136-5

- Lazenby, J.F, The First Punic War, p. 175

- Polybius 3.10.4

- Polybius 1.61.1

- Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars, p. 125

- Polybius 3.9.6, Livy 21.1.5

- Appian Iberia 4

- Lancel, Serge, Hannibal, p. 28

- Cornelius Nepos, Hamilcar III.2

- Livy 21.3.1.4

- Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars, p. 142

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage, p. 148

- Polybius 2.1.9

- Appian Hamilcar 7.2, 6.5, Zonaras 8.17

- Miles, Richard, Carthage Must be Destroyed, p. 198, ISBN 978-0-141-01809-6

- Diodorus Siculus 25.10

- Polybius 2.1.6

- Diodorus Siculus 25.10.1

- Polybius 3.11, Livy 21.1.4

- O’Connell, Robert L, The Ghosts of Cannae, p. 80, ISBN 978-1-4000-6702-2

- Carey, Brian T, Cairns John, Allfree Joshua B, Hannibal's Last Battle, p. 40 ISBN 978-1-59416-075-2

- Prevas, John, Hannibal Crosses The Alps, p. 41 ISBN 0-306-81070-0

- Cottrell, Tony, Hannibal's campaigns, p. 18 ISBN 0-88029-817-0

- Bath, Tony, Hannibal's campaigns, p. 21

- Baker, G.P, Hannibal, p. 70 note 2

- Lancel, Serge, Hannibal's campaigns, p. 18 ISBN 0-88029-817-0

- Strabo V. 158

- Lancel, Serge, Hannibal, pp. 30–31

- Thucidides 1.13.6

- Strabo 3.156, 3.159

- Justin XLIII.5

- Lancel, Serge, Hannibal, p. 35

- Diodorus Siculus 25.10.1–2

- Diodorus Siculus 25.10.2

- Miles, Richard, Carthage Must be Destroyed, p. 198

- Strabo 3.2.14

- A. E. Astin (1989). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1.

- Diodorus Siculus 25.10.3

- Livy 24.14.3–4

- Cassius Dio fr. 48

- Lancel, Serge, Hannibal, p. 37

- Cornelius Nepos, Hamilcar, 4.2

- Diodorus Siculus25.10.3–4

- Zonaras 8.19

- Appian, Iberia, 6.1.5

- Polybius 2.1.8

- Oros. vii. 143; Miñano, Diccion. vol. i. p. 391; Auson. Epist. xxiv. 68, 69, Punica Barcino

- Michael Dietler; Carolina López-Ruiz (15 October 2009). Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-226-14848-9.

- Polybius, 1.78

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage, p. 95 ISBN 0-304-36642-0

- Plutarch, Cato Major, 8, 14

- Polybius 1.88.7

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Caspari, Maximilian Otto Bismarck (1911). "Hamilcar Barca". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 877–878.

- Baker, G. P. (1999). Hannibal. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1005-0.

- Bath, Tony (1995). Hannibal's Campaigns. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-88029-817-0. or Patrick Stephens, Cambridge, England 1981. ISBN 0-85059-492-8.

- Bagnall, Nigel (2005). The Punic Wars. New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-34214-4.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2003). The Fall of Carthage. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36642-0.

- Geus, Klaus (1994), Prosopographie der Literarisch Bezeugten Karthager, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, Vol. 59, Studia Phoenica, No. 13, Leuven: Peeters, ISBN 9789068316438. (in German)

- Hoyos, Dexter (2007). Truceless War: Carthage's Fight for Survival, 241 to 237 BC. Leiden, Netherlands; Boston, Massachusetts: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2192-4.

- Huss, Werner (1985), Geschichte der Karthager, Munich: C.H. Beck, ISBN 9783406306549. (in German)

- Lancel, Serge (1999). Hannibal. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-21848-3.

- Lazenby, John Francis (1998). Hannibal's War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3004-0.

- Lazenby, John Francis (1996). The First Punic War. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 1-85728-136-5.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Rankov, Boris (2015) [2011]. "A War of Phases: Strategies and Stalemates". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 149–166. ISBN 978-1-4051-7600-2.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 7, Part 2, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

Further reading

- Warry, John (1993). Warfare in The Classical World. Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 1-56619-463-6.

- Lancel, Serge (1997). Carthage A History. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-57718-103-4.

External links

- Livius.org: Hamilcar Barca Archived 2013-01-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Cornelius Nepos: Life of Hamilcar