Guadalquivir

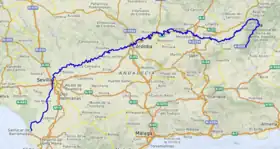

The Guadalquivir (/ˌɡwɑːdəlkɪˈvɪər/, also UK: /-kwɪˈ-/, US: /-kiːˈ-, ˌɡwɑːdəlˈkwɪvər/,[1][2][3] Spanish: [ɡwaðalkiˈβiɾ], Arabic: اَلْوَادِي الْكَبِيرْ, lit. 'the big river') is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The river is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from Seville to the Gulf of Cádiz, but in Roman times it was navigable from Córdoba.

| Guadalquivir | |

|---|---|

Montoro situated on a bend of the river. | |

Location of the Guadalquivir | |

| Etymology | from الوادي الكبير (al-wādī l-kabīr), "the great valley" or "the great river" in Arabic |

| Location | |

| Country | Spain |

| Region | Andalusia |

| Cities | Córdoba, Seville |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Cañada de las Fuentes |

| • location | Cazorla Range, Quesada, Jaén |

| Mouth | Atlantic Ocean |

• location | Almonte (Huelva) and Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz). |

• coordinates | 36°47′N 6°21′W |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 657 km (408 mi) |

| Basin size | 56,978 km2 (21,999 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Almonte (Huelva) and Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz). |

| • average | 164.3 m3/s (5,800 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Guadiana Menor, Guadalbullón, Guadajoz, Genil, Corbones, Guadaira |

| • right | Guadalimar, Jándula, Yeguas, Guadalmellato, Guadiato, Bembézar, Viar, Rivera de Huelva, Guadiamar |

Geography

The river is 657 km (408 mi) long and drains an area of about 58,000 km2 (22,000 sq mi). It rises at Cañada de las Fuentes (village of Quesada) in the Cazorla mountain range (Jaén), flows through Córdoba and Seville and reaches the sea between the municipalities of Almonte and the fishing village of Bonanza, in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, flowing into the Gulf of Cádiz, in the Atlantic Ocean.

The marshy lowlands at the river's mouth are known as "Las Marismas". The river borders the Doñana National Park reserve.

Name

The modern name of Guadalquivir comes from the Arabic al-wādī l-kabīr (اَلْوَادِي الْكَبِيرْ), meaning "the big river".[4][5]

There was a variety of names for the Guadalquivir in Classical and pre-Classical times. According to Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 28, the native people of Tartessians or Turdetanians called the river by two names: Certis (Kertis) and Rherkēs (Ῥέρκης).[6] Greek geographers sometimes called it "the river of Tartessos", after the city of that name. The Romans called it by the name Baetis (which was the basis for name of the province of Hispania Baetica).

History

During a significant portion of the Holocene, the western Guadalquivir valley was occupied by an inland sea, the Tartessian Gulf.[7]

The Phoenicians established the first anchorage grounds and dealt in precious metals. The ancient city of Tartessos (that gave its name to the Tartessian Civilization) was said to have been located at the mouth of the Guadalquivir, although its site has not yet been found.

The Romans, whose name for the river was Baetis, settled in Hispalis (Seville), in the 2nd century BC, making it into an important river port. By the 1st century BC, Hispalis was a walled city with shipyards building longboats to carry wheat. In the 1st century AD the Hispalis was home to entire naval squadrons. Ships sailed to Rome with various products: minerals, salt, fish, etc. During the Arab rule between 712 and 1248 the Moors built a stone dock and the Torre del Oro (Tower of Gold), to reinforce the port defences.

In the 13th century Ferdinand III expanded the shipyards and from Seville's busy port, grain, oil, wine, wool, leather, cheese, honey, wax, nuts and dried fruit, salted fish, metal, silk, linen and dye were exported throughout Europe.

A reconstructed waterwheel is located at Córdoba on the Guadalquivir River. The Molino de la Albolafia waterwheel, originally built by the Romans, provided water for the nearby Alcázar gardens as well as being used to mill flour.[8]

After the discovery of the Americas, Seville became the economic centre of the Spanish Empire as its port monopolised the trans-oceanic trade and the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) wielded its power. As navigation of the Guadalquivir River became increasingly difficult, Seville's trade monopoly was lost to Cádiz. The construction of the canal known as the Corta de Merlina in 1794 marked the beginning of the modernisation of the port of Seville.

After five years of work (2005–2010), in late November 2010 the new Seville lock designed to regulate tides was finally in operation.

Flooding

The Guadalquivir River Basin occupies an area of 63,085 km² and has a long history of severe flooding.

During the winter of 2010 heavy rainfall caused severe flooding in rural and agricultural areas in the provinces of Seville, Córdoba and Jaén in the Andalusia region. The accumulated rainfall in the month of February was above 250 mm (10 in), double the precipitation for Spain for that month. In March 2010 several tributaries of the Guadalquivir flooded, causing over 1,500 people to flee their homes as a result of the increased flow of the Guadalquivir, which on 6 March 2010 reached 2,000 m3/s (71,000 cu ft/s) in Córdoba and 2,700 m3/s (95,000 cu ft/s) in Seville. This was below that recorded in Seville in the flood of 1963 when 6,000 m3/s (210,000 cu ft/s). was reached. During August 2010, when flooding occurred in Jaén, Córdoba and Seville, three people died in Córdoba.[9]

Pollution

The Doñana disaster, also known as the Aznalcóllar Disaster or Guadiamar Disaster was an industrial accident in Andalusia. In April 1998 a holding dam burst at the Los Frailes mine, near Aznalcóllar, Seville Province, releasing 4 to 5 million cubic metres (140 to 180 million cubic feet) of mine tailings. The Doñana National Park was also affected by this event.

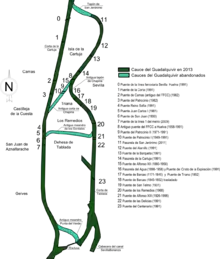

Dams and bridges

Of the numerous bridges spanning the Guadalquivir, one of the oldest is the Roman bridge of Córdoba. Significant bridges at Seville include the Puente del Alamillo (1992), Puente de Isabel II or Puente de Triana (1852), and Puente del Centenario (completed in 1992).[10]

The El Tranco de Beas Dam at the head of the river was built between 1929 and 1944 as a hydroelectricity project of the Franco regime. Doña Aldonza Dam is located in the Guadalquivir riverbed, in the Andalusian municipalities of Úbeda, Peal de Becerro and Torreperogil in the province of Jaén.

Ports

The Port of Seville is the main port on the Guadalquivir River. The Port Authority of Seville is responsible for developing, managing, operating, and marketing the Port of Seville.

The entrance to the Port of Seville is protected by a lock that regulates the water level, making the port free of tidal influences. The Port of Seville has over 2,700 m (8,900 ft) of berths for public use and 1,100 m (3,600 ft) of private berths. These docks and berths are used for solid and liquid bulk cargoes, roll-on/roll-off cargoes, containers, private vessels and cruise ships.[11]

In 2001, the Port of Seville handled almost 4.9 million tonnes (5.4 million short tons) of cargo, including 3.0 million tonnes (3.3 million short tons) of solid bulk, 1.6 million tonnes (1.8 million short tons) of general cargo, and over 264,000 tonnes (291,000 short tons) of liquid bulk. Almost 1,500 vessels brought cargo into the port, including more than 101,000 TEUs of containerized cargo.[11]

See also

References

- "Guadalquivir". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Guadalquivir" (US) and "Guadalquivir". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01.

- "Guadalquivir". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Rafael Valencia (1992). "Islamic Seville: Its Political, Social and Cultural History". In Salma Khadra Jayyusi; Manuela Marín (eds.). The Legacy of Muslim Spain. Brill. p. 136. ISBN 90-04-09599-3.

- Eric Ziolkowski (28 October 2014). "Kierkegaard's Subterranean Fluvial Pseudonymity". In Jon Stewart; Katalin Nun (eds.). Volume 16, Tome I: Kierkegaard's Literary Figures and Motifs: Agamemnon to Guadalquivir. Vol. 16. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-4724-4136-2.

- Smith, William. "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), BAETIS". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Abril, José-María; Periáñez, Raúl; Escacena, José-Luis (December 2013). "Modeling tides and tsunami propagation in the former Gulf of Tartessos, as a tool for Archaeological Science". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (12): 4499–4508. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.4499A. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.030. hdl:11441/135755.

- "Córdoba Molino de Albolafia mill, The city of Córdoba tourist main sights, Andalusia, southern Spain". Andalucia.com. 19 October 2011. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- "Spain Water Problem: The Guadalquivir river ne". Tobaccoirrigation.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- José Luis Munuera Alemán (2010). Casos de éxito de las empresas murcianas. ESIC Editorial. p. 116. ISBN 978-84-7356-670-4.

- "Port of Seville". World Port Source.