Hanover school of architecture

The Hanoverian school of architecture or Hanover School is a school of architecture that was popular in Northern Germany in the second half of the 19th century, characterized by a move away from classicism and neo-Baroque and distinguished by a turn towards the neo-Gothic. Its founder, the architect Conrad Wilhelm Hase, designed almost 80 new church buildings and over 60 civil buildings alone. In addition, Hase taught for 45 years at the Polytechnic University in Hanover and trained around 1000 full-time architects, many of whom adopted his style principles.[1]: 11

The expanding industrialization of nineteenth-century Germany favored the development of the Hanover School, especially in urban areas, where a rapidly-growing population led to a great demand for new homes, schools and hospitals.[1]: 188, 275 The expansion of the railway network required new structures such as station and company buildings, and emerging industrial corporations built impressive factory structures that reflected their economic importance.[2] Hanover itself saw the construction of numerous large municipal churches, schools, and factories as well as several thousand residences between the 1850s and the beginning of the 20th century.[1]: 9 Stylistically, these buildings were characterized by their unplastered brick facades, which were perceived as "honest."[1]: 169 Especially for factory buildings, it was already possible to recognize its internal function by the outer shape of a building.[1]: 315 Exterior ornament used a number of design elements: stepped gables with finials, carved stone, and decoratively set bricks with a glazed surface derived from medieval church buildings.[1]: 442

For a long time after the Second World War, during which most large German cities were heavily bombed, the remaining buildings, especially in Hanover, garnered little interest in monument preservation. Large-scale transformation measures and the conversion of Hanover into a car-friendly city led to numerous demolitions.[3]: 234

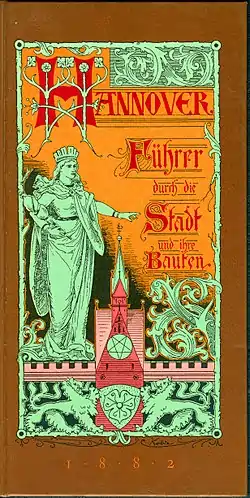

The term "Hanover School of Architecture" probably first appeared in 1882 with Theodor Unger.[4]: 107 [5] At the time, however, the term also referred to the previously popular Rundbogenstil ("round-arched style" or Romanesque revival style) and the buildings shaped by Hase's influence. It was only later on that only the buildings designed according to Hase's teachings were counted as the "classic" Hanover School.[6]: 95

Origins

The Hanover School was preceded by the phase of the Rundbogenstil, which lasted from about 1835 to 1865. This current was also a manifestation of historicism; that is, a revival and recombination of elements of older styles of architecture. The Hanoverian strand of the Rundbogenstil was not only widespread in the city itself, but also in the Kingdom of Hanover. Two branches of it can be distinguished: (1) the "Tramm style" (Tramm-stil) developed by court councilor Christian Heinrich Tramm, characterized by staves and corner pole towers, and (2) the style founded by city builder August Heinrich Andreae with three-dimensional brickwork.[1]: 10–11

The Hanoverian Church consistorial master builder and architecture professor Conrad Wilhelm Hase (1818–1902) took up the variation of Andreae's Rundbogenstil starting around 1853 and from it developed the formal vocabularies of the Hannover School.[1]: 11 It is worth noting that the architectural theory of Berlin's Karl Friedrich Schinkel, the "Schinkelschule," at the Bauakademie, had no influence here.[6]: 93 After a transitional period, the Hanover School coalesced independently around 1860. Its heyday lasted until about 1900; in exceptional cases it was used until the beginning of the First World War, and extended over northern Germany, as well as to a certain extent abroad.[1]: 11

Ulrike Faber-Hermann observed in 1989 that the Hanover School's "appearance can be described by certain characteristics," but that a precise "definition" remains vague, partly because at the time of its creation the style was "multilayered." For example, in 1882, the Hanover School architect Theodor Unger was employing both the Rundbogenstil and the Gothic forms of Hase. According to Faber-Hermann, only the latter were later associated with the concept of the Hanover School. On closer inspection, many students of Hase did not allow themselves to be characterized as strict representatives of this school, and only a few buildings assigned to the Hanover School are actually precise classic examples of its designers' work.[6]: 95

Conrad Wilhelm Hase's design work became the driving force for the Hanover School, aided by Hase's teaching position at the Technical University in Hanover (until 1879 it was still called the Hanover Polytechnic School), which obviously ensured the dissemination of his ideas. From 1849 to 1894, his teaching activities there included, among other things, subjects such as designing public and private buildings, sacred architecture, formal theories of medieval architecture, and ornament.[1]: 11 Hase tried in his work to detach from the classicism represented by Georg Ludwig Friedrich Laves as well as from the neo-baroque tendencies borrowed from France in favor of medieval forms, which he considered stylistically pure. The architect Friedrich von Gärtner, who taught in Vienna, exerted great influence on Hase with his position that unplastered stone should be used as the primary building material (otherwise called "pure construction").[6]: 93 In the 45 years that Hase taught at the university, around 35,000 students were enrolled in architecture subjects, of which only around 1000 completed the degree program in architecture and thus can be regarded as a direct student of Hase–still an impressive number.[1]: 11 Hanoverian training in architecture enjoyed supra-regional recognition, so that students came from all over northern Germany, as well as from the Americas, England, the Netherlands and especially from Norway. Hase's successor at the university, Karl Mohrmann, continued the Gothic-revival program of his predecessor until 1924.[1]: 11

The Role of the Railway

The invention of the railway was of critical importance for nineteenth-century industrialization.[2]: 4–5 In Lower Saxony, the development of the rail network and the formation of the Hanover School overlapped over several decades. Many architects who adhered to the architectural style were also active in railway construction, including Hase and some of his employees.

The railway fueled the rapid transport of goods and people, opened up rural regions to development, and ensured a strong economy.[2]: 4–5 Initially, economics played a major role and freight transport enjoyed greater interest before passenger transport also became more important a few years later.[7]: 16 The technical innovations emanating from the railway also had an impact on art and architecture, and they also determined village and urban development. In many places, the stations shaped the cityscape themselves. In Lower Saxony, brick construction was favored in station design after 1850.[2]: 4–5 After a trip through Germany in 1857, the British architect George Gilbert Scott expressed his appreciation: "The best developments of railway architecture I have seen are on the Hanoverian lines."[8] The development of the railway in Lower Saxony was already well-established by this point, as the first section, the route from Braunschweig to Wolfenbüttel, had begun operation at the end of 1838.[2]: 16 By 1880, all of the most important lines had been completed, and in the following decades only additional feeder lines and secondary railways were constructed.[2]: 21

Scientists from the Institute of Building and Art History of the University of Hanover identified a total of 480 buildings in Lower Saxony in the early 1980s that they classified as "scientifically remarkable."[7]: 10–11 In addition to the principal passenger railway depots, they also looked at other auxiliary railway structures, such as signal boxes, repair halls, post houses and railway housing. Their research revealed various architectural "style development stages" according to which the buildings were designed. According to the inventory published in 1983, an "independent design language based on the round arch style of the Hannover School" developed from 1852 to 1865, while over the next two decades the neo-Gothic of the Hannoversche Schule was then applied "irregularly."[7]: 10 According to this study, many innovations took place in the field of "small architecture"–that is, minor stations, as well as in the first-generation structures that were later replaced by larger successor buildings (for example, the stations in Hanover, Uelzen or Oldenburg). The innovations concerned architecture as well as urban planning and technology.[2]: 5

Many Gothic-revival railway stations were built along the Hannöversche Südbahn from Hanover to Göttingen. The route was already planned in 1845, but its completion was delayed due to the uncertain political situation before the Revolutions of 1848.[7]: 19 The first section, from Hanover to Alfeld, was inaugurated in May 1853, and the section to Göttingen followed a year later. Hase was commissioned to design many of these buildings, presumably in cooperation with Julius Rasch and Adolf Funk. Stylistically, these buildings reveal the transition from the Rundbogenstil to the Hanover School, especially structures such as the main station building in Sarstedt from 1855. The brick building, painted today, is divided vertically with lisens. Its middle transverse section uses a blind gable, which was decorated at the roofline.[7]: 96 Other Hase stations on this route can be found in Nordstemmen (1858–1860), Elze (1855), Einbeck (then Salzderhelden, 1855) and Göttingen (1855). In Banteln and Freden, the stations show elements of the Rundbogenstil, but probably were only built between 1865 and 1870.[7]: 97–105

Contemporary Reception

In 1882, Theodor Unger published the first comprehensive presentation of the buildings of the Hanover School. It appeared in the first architectural guide of the city - Hannover: Führer durch die Stadt und ihre Bauten (Hanover: Guide through the city and its buildings) - and consisted of a juxtaposition of the Hanover School with the Hanoverian buildings of the Renaissance. Unger attested that the new style had given the city a "highly characteristic and interesting external appearance." Its supporters saw the Hanover School as a "universal style" that had to be used for all building types, from churches to buildings of secular and pedestrian functions. Because of this far-reaching claim, there were also numerous critical voices and rejections, which Unger also addressed in his publication.

In Unger's architectural guide, the Berlin architect Hubert Stier, who had recently designed Hanover Central Station, also commented on the "Renaissance buildings" in Hanover. He counted among these "artically remarkable" monumental and private buildings, for which "real materials" had been used in the pursuit of "genuine monumentality." The buildings are determined by the medieval echoes and distinguished themselves as "advantageous" compared to other contemporary buildings. Both critics, Unger and Stier, judged the Hanover School from a certain distance: Unger had belonged to the Vienna School around Friedrich von Schmidt, while Stier belonged to the Berlin School.

Supporters of the School

During his teaching at the Polytechnic School Hannover, Conrad Wilhelm Hase trained about 1000 full-time architects. Some of his students support Hase at the university and represented the teachings of neo-Gothic as his assistants or as professors and private lecturers. These circles included Wilhelm Lüer (from 1858), Arthur Schröder (from 1869), Werner Schuch (from 1872), Max Kolde (from 1883), Gustav Schönermark (from 1885), Theodor Schlieben (from 1890) and Eduard Schlöbcke (from 1895). After Hase's departure from the Technical University, Karl Mohrmann succeeded him and continued to continue his predecessor's teaching opinion in a partly modified form until 1924.[1]: 11 In addition to the university, Hase's students also taught as teachers at the Hanover School of Applied Arts (Otto Bollweg,[1]: 519 [1]: 529 Adolf Narten,[1]: 553 and Hermann Narten[1]: 553 ). Many students were also working at building trade schools, for example at the Baugewerkschule Eckernförde (Erich Apolant, in Hamburg (Hugo Groothoff) or in Nienburg (Otto Blanke, Wilhelm Schultz. At the important first North German building trade school in Holzminden, there was a circle of Hase admirers with the Lehrerverein Kunstclubb in the 1860s, who sought to spread the Hanover School (Carl Schäfer).[1]: 561

Important Members

- Ludwig Droste (1814–1875): Droste studied with Gärtner in Munich and initially worked as a private architect in Mannheim before he was sworn in as a city builder in Hanover in 1849. Together with others, he founded the Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein Hannover (Hanover Architects' and Engineers Association). Droste is considered a representative of the round arch style; his works in Hanover include the Kaiser-Wilhelm- und Ratsgymnasium Hannover (Lyceum) on Georgsplatz, the restoration of the Marktkirche, the Packhof, the entrance building of the Engesohder Cemetery and several other school buildings (Bürgerschule, Am Clevertore; Höhere Töchterschule, Am Graben; Stadttöchterschule, Am Aegi).[1]: 522

- Conrad Wilhelm Hase (1818-1902):Hase first learned at the Polytechnic School Hannover (the later university), then at the University of Göttingen, which was joined by a masonry apprenticeship. Before starting his 45-year teaching at the University of Hanover in 1849, Hase worked for the Royal Hanover Railway Directorate. During his time as a university lecturer, he received the titles of building inspector (1852), building councilor (1858) and professor (1878). The founder of the Hannover School was also a part-time consistory official at the Evangelisch-lutherische Landeskirche Hannovers (Protestant Lutheran State Church of Hanover) and honorary citizen of Einbeck and Hildesheim. For the period 1848-52, Hase's designs can be attributed to the round arch style, after which he represented various tendencies of neo-Gothic in 1853–59, and then trained his personal style of neo-Gothic from 1859. In the course of his life, Hase created a large number of very different buildings in large parts of northern Germany. Some examples are: Christuskirche Hannover, katholische Kirche Peine, Erlöserkirche Hannover, Apostelkirche Hannover, tower extension of Martinskirche Linden (today Hanover), extension of the Old Town Hall Hannover, Andreanum Hildesheim, stations of Lehrte, Celle, Bremen, Wunstorf, Göttingen, Nordstemmen, Oldenburg, Marienburg Palace, Hildesheim Post Office, Hanover Künstlerhaus, and the Klagesmarkt-Apotheke Hannover.[1]: 531–533

.jpg.webp) Conrad Wilhelm Hase

Conrad Wilhelm Hase - Hermann Hunaeus (1812–1893): Like Ludwig Droste, Hunaeus also studied with Friedrich von Gärtner in Munich. From 1836 he worked as a military engineer in Hanover, then as a senior government and building councilor, later as a secret building councilor. Hunaeus, also a co-founder of the Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein Hannover, is considered a representative of the Rundbogenstil. Among other things, he created various wings of the royal Dicasterien building in Hanover (Am Archiv, Archivstraße), the residences of Johann Egestorff, Wilhelm Glahn and Hermann Cohen, the military hospital on Adolfstraße in Hanover; the house of the military clothing commission, also on Adolfstraße; and the teaching seminary of Wunstorf. He also converted the Welfenschloss in Hanover into a Technical University (Teschnischen Hochschule).[1]: 538

- Franz Andreas Meyer (1837-1901): Meyer studied at the Polytechnic School Hannover and worked during the second phase of his studies in Hase's office. After his studies, he started as an assistant engineer for the Royal Railway Directorate in Hanover (1860) and then moved to Hamburg (1862), where he became the chief engineer of the building deputation (1872). He continued to keep in touch with Hase and provided many of his students with the Hamburg building deputation. Meyer was co-founder of the Niedersächsische and Hamburger Bauhütte, as well as chairman of the Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein Hamburg. Meyer's plans include the supervision of the entire Speicherstadt in the Free Port of Hamburg, for which he designed numerous storage buildings himself. In addition, the customs building and the portal of the new Elbe bridge are his work.[1]: 549–550

- Karl Mohrmann (1857-1927): Mohrmann studied at the Polytechnic School Hanover with Hase (until 1879), whose successor he would later become there. After his studies, he was initially in the Prussian civil service before becoming a private lecturer in architecture in Hanover. After working in Hase's office, he moved to Riga (1887-1892) for five years as a professor of civil engineering. Back in Hanover, he inherited Hase in 1894 as a professor of medieval architecture. He also took over the chairmanship of the Bauhütte zum weißen Blatt (see below) founded by Hase (from 1902). Mohrmann managed to further develop the principles of the Hanover School and to maintain its influence until the 1920s. His work includes the restoration of the cathedral in Riga, his own residence at Herrenhäuser Kirchweg in Hanover, the Protestant Martin Luther Church in Bremen and other churches in Hanover, Bremen and Oldenburg.[1]: 551

- Edwin Oppler (1831-1880): Oppler was also one of Hase's students at the Polytechnic School Hannover (until 1854) and worked in his teacher's office. After his studies, he gained experience in Belgium and France and then worked as a private architect in Hanover (from 1861); Oppler was also a member of the Hanover Architects' and Engineers Association. Among others, he has the Villa Solms, the Jüdischer Friedhof An der Strangriede (Jewish Cemetery on Strangriede), the New Synagogue, and the Israelite School as well as Hagerhof Castle in Bad Honnef and other residential buildings and synagogues in Wroclaw, Karlovy Vary, Norderney and Hamelin.[1]: 554

Edwin Oppler

Edwin Oppler - Julius Rasch (1830-1887): Rasch began his studies at the Polytechnic School Hannover under Christian Heinrich Tramm and at the same time worked in the central office of the Hanover Railway, of which he became an architect after his studies (1852). Here he rose from construction contractor to construction inspector before moving to Alfred Krupp in Essen in 1875. From 1875, he worked as a government and building councilor in Berlin. Together with Hase and Adolf Funk, he designed numerous stations, including: Alfeld, Elze, Göttingen, Hannover-Münden, Leer, Papenburg, Nordstemmen. He also constructed the management building of the Hannoversche Eisenbahn in Joachimstraße in Hanover, as well as some residential buildings.[1]: 558

- Christian Heinrich Tramm (1819-1861): Tramm first studied at the Polytechnic School Hannover (from 1835) and then moved to Gärtner in Munich (1838–1840). After his studies, Tramm returned to Hanover to work there as a farm construction conductor; he also worked for Laves. Tramm is considered a follower of the round arch style, whose stave variant he developed. His works in Hanover include the horse stable in Georgengarten, Villa Kaulbach am Waterlooplatz and Villa Simon on Brühlstraße. The Welfenschloss and the building wing of the Henriettenstift to Marienstraße are particularly influential in urban planning.[1]: 570

Die Bauhütte

In November 1880, Hase founded the association called the Bauhütte zum weißen Blatt (literally, "Construction Hut as a White Sheet") to counteract the dwindling influence of his work. In the late 1870s, the situation for the Hanover School had changed: After the founding of the German Empire, there was a construction boom, while the various architecture schools were increasingly consolidated. In addition, the importance of the Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein Hannover grew at the expense of Hase's own activity. The chosen name addition "to the white sheet" is probably an allusion to the Hanoverian Masonic lodge Friedrich zum weißen Pferde, whose members included Georg Ludwig Friedrich Laves. The concept of the Bauhütte provided that a member first had to submit his designs to his colleagues for examination. By forming a unified style, the artistic quality of the buildings was to be further increased. The mission statement of the Bauhütte was recorded in several mottos that coincided with Hase's principles:[1]: 103–105

- Equality before art: The work of a teacher is not per se more valuable than that of his student, only the creative power of a person counts.

- Friendship in the hut: The members of the Bauhütte compete together against the advocates of other styles and are connected to each other in friendship. This was important because the members competed not only with the supporters of other schools, but also with each other for commissions.

- Truth in Art: This principle refers to the controversial use of unplastered bricks as a visible raw material. Any material should be considered "real" if it is used correctly.

- Stick to the old: This should encourage members to self-criticize. It is important to respect the art of the past and not to overestimate one's own current construction projects in their importance. This principle was often misunderstood as a reactionary tenet of the members.[1]: 105

However, as early as the 1880s and 1890s, many students of Hase deviated from his strict principles.[6]: 94

Stylistic Branches

Rundbogenstil Branch

In the middle of the 19th, the Hanoverian architects increasingly set themselves apart from Laves' "Klassizismus" (classicism).[1]: 31–32 Between 1845–56, Ernst Ebeling and later Hermann Hunaeus built the General Military Hospital (now demolished) in the Calenberg Neustadt of Hanover. While Ebeling still envisioned a plastered facade for this building, Hunaeus changed the plans for a version with visible bricks and sandstone after Ebeling's death. Ludwig Droste already applied the Tramm-Style for the Lyceum (later the Kaiser-Wilhelm- und Ratsgymnasium) on Georgsplatz (now demolished), and red bricks and sandstone were also shown open here. Tramm himself designed the Welfenschloss between 1857–66, which later became the main building of the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover . According to the architectural historian Günther Kokkelink, his characteristic spandrels and other structural details make it one of the "most mature form[s]" of the Tramm style.[1]: 39 Kokkelink sees the later Künstlerhaus Hannover, built from 1853–56 as a museum for art and science, as a further development of the sculptural-spatial variety of the Rundbogenstil. The architect, Hase, designed the exterior with different colored bricks and some sandstone details, with which he emphasized the "beauty of the material." The Künstlerhaus marks the high point of the Rundbogenstil in Hanover, which spread quite late compared to other cities and had more variations than elsewhere.[1]: 31–32

Other examples of the round arch style in Hanover are the House of the Military Clothing Commission (Hermann Hunaeus, 1859/1860),[1]: 41 the buildings of the Henriettenstift located to Marienstraße (Christian Heinrich Tramm, 1861–1863),[1]: 80 the Marstall at Welfenschloss (Eduard Heldberg, 1863–1865),[1]: 79 and the double townhouses Prinzenstraße 4 and 6 (Georg Hagemann, 1869).[1]: 53–54

House of the Military Clothing Commission in Hannover-Calenberger Neustadt (52.368802°N 9.723927°E)

House of the Military Clothing Commission in Hannover-Calenberger Neustadt (52.368802°N 9.723927°E) Henriettenstift in Hanover's Südstadt (52.369796°N 9.755042°E)

Henriettenstift in Hanover's Südstadt (52.369796°N 9.755042°E) Marstall in Nord (Hanover) (52.381900°N 9.720375°E)

Marstall in Nord (Hanover) (52.381900°N 9.720375°E) Double townhouses Prinzenstraße 4 and 6 in Hannover-Mitte (52.373842°N 9.744550°E)

Double townhouses Prinzenstraße 4 and 6 in Hannover-Mitte (52.373842°N 9.744550°E)

Gothic-Revival Branch

Hase's architectural style - occasionally called "hatemic" by followers and critics - was characterized by medieval brick Gothic, whereby the statics of the buildings and the preferably domestic building material used (wood, brick, sandstone) should remain visible to the viewer. The brick shell facades, which are recognizable by the absence of external plaster, received brick decorations, often glazed bricks and forms German banded friezes and dentils. Staggered gables at the edges and segment arches are used frequently over windows and doors (as in the Rundbogenstil).

"Moving" rooflines are a characteristic feature of the Hanover School. In addition to bay windows and turrets, the architects often used decorative gables in their designs. Conrad Wilhelm Hase started this trend in Hanover by adding to his own house a small, brick ornamental gable with radial finials in 1860/61. A short time later, in 1864–65, his students Wilhelm Hauers and Wilhelm Schultz took over these stylistic devices for the gym of the Turn-Klubbe Hannover on Maschstraße in Hanover. A superimposed gable was placed here on a triangular one, which, in the opinion of the architectural historian Günther Kokkelink, creatively deviated from the medieval models. Over the next few years, the brick industry made some technical advances and was able to deliver increasingly diverse molding stones, which allowed architects to design increasingly complex rooflines. Ludwig Frühling, who had the manufacturer's Villa Schwarz built in Hanover's Parkstraße (today Wilhelm-Busch-Straße) built in 1886, with decorative gables similar to those of the Hanover Town Hall also benefited from this. Karl Börgemann's Grönes Hus from 1899 in the Hanover Sextrostraße surpassed previous buildings in imaginative design with his facade and roof landscape, Kokkelink speaks here of a "fantastic development of the corner final gable." The house has thus moved further and further away from the peculiarities of medieval construction and marks the transition from Gothic-revival to Art Nouveau.[1]: 121

The visible use of bricks to veneer facades played a decisive role in the Hanover School. The "brick dimension" determined the design of the walls and ensured an "even horizontal layering," as Theodor Unger put it in his architectural guide in 1882.[4]: 116–118 The joints occurring between the stones divide the building; all surfaces, friezes, columns can be broken down into a certain number of brick layers.[1]: 442–443 In order to ornament the buildings with decorative details, architects and master masons had numerous means at their disposal: they used shaped stones or used polychrome colored bricks on a facade (for example, in red and yellow, as in the Clementinenhaus). In addition, glazed bricks were used in different colors (for example in brown, black and green). However, Theodor Unger proved to be an outspoken opponent of the glazed bricks, to which he said an "offensive effect."He took the view that glazes belonged from brick construction "banished" or at least "rived back to an extremely modest level".[4]: 120 and 121

Many pronounced decorative elements adorned the magnificent villas of the Hanover School, but numerous details also can be seen in more pedestrian structures, which often are only noticed at a second glance. According to Kokkelink, the architects Karl Börgemann and Karl Mohrmann proceeded particularly boldly; Kokkelink describes them as "brick virtuosos [...] that span all levels of Hanoverian brick architecture."[1]: 442–3 For example, in the de:Villa Willmer by Börgemann, the tower and window bands show an "immense wealth of forms." Börgemann's Heilig-Geist-Spital und Stift (Holy Spirit Hospital) received extensive ornamental surfaces and contrasting, colored glazed bricks on the walls. According to Kokkelink, Jugendstil is already evident here with three-dimensional foliage visible in the ornament. However, the architect remains true to the concept of continuous joints and applies them both horizontally and diagonally. Börgemann's preference for glazed bricks is most pronounced in the Grönen Hus. Here he worked particularly clearly with the complementary contrast between green and red stones. According to Kokkelink, "particularly attractive glazes...come into their own...in this house." Gröne Hus represents a transition from the Hanover School to Art Nouveau. Karl Mohrmann's own house on Herrenhäuser Kirchweg also deviates greatly from the "classic" teaching in his details, as the gables exhibit brightly plastered surfaces for decoration. In addition, many other lesser-known architects used the building material in creative ways. An example of this is Friedrich Wedel, another Hase student, who used decorative shaped stones for the residential and commercial building he designed at Callinstraße 4.[1]: 442

Holy Spirit Hospital and Monastery decorated with foliage and ornamental elements (52.367697°N 9.768307°E)

Holy Spirit Hospital and Monastery decorated with foliage and ornamental elements (52.367697°N 9.768307°E) Brick fence pillar with rhythmically applied glazed stones on the Holy Spirit Hospital (52.368591°N 9.770286°E)

Brick fence pillar with rhythmically applied glazed stones on the Holy Spirit Hospital (52.368591°N 9.770286°E) Apartment house on Callinstrasse 4 in the Nordstadt (52.386267°N 9.716919°E)

Apartment house on Callinstrasse 4 in the Nordstadt (52.386267°N 9.716919°E) Special shaped bricks on the Turn-Klubbe gymnasium (52.366282°N 9.743152°E)

Special shaped bricks on the Turn-Klubbe gymnasium (52.366282°N 9.743152°E)

Exemplary Building Typologies

Religious Buildings

The sacred buildings of the Hannover School occupy a special position. Many supporters worked primarily in the construction of churches, including Johannes Otzen, Christoph Hehl, Johannes Franziskus Klomp, Johannes Vollmer and Eduard Endler. Conrad Wilhelm Hase also focused on this: He worked on 171 church construction projects (including 76 new buildings), he created 66 on civil buildings. The Hanover School was therefore often classified as a "church style" in the past. However, this assessment falls far short in view of countless residential buildings, factories, schools, post offices and hospitals.

In Germany, it occurred in the second half of the 19th century. century to a lively construction activity at churches, the peak of which was between 1880 and 1914. The reason for this was essentially the growing urban population, triggered by industrialization. New districts outside the old city center were created, new parishes were founded in many places. In Hanover, this phase began with the sensational construction of the Christian Church in 1859. For Ulrike Faber-Hermann, this is considered "the actual founding building of the Hannoversche [sic] Schule", Günther Kokkelink writes of an "architectural sensation". The church became unusually large and magnificent. According to Kokkelink, the very finely designed, detailed roof landscape is typical of the early phase of the Hanover School. In the plastic structure of the building, on the other hand, the Christ Church resembodies later buildings.Hase also succeeded in implementing the entrance area "cooked composition": The western cornerstones of the tower are so advanced that in between there is space for an arched vestibule, which crowned hare with a "powerful eyelash". The new construction of the Christuskirche in Hanover remained without further an example for a long time. It was only almost 20 years later, from 1878 to 1882, that the next large city church was built in Linden with the Zion Church (today: Erlöserkirche).Within a few years, the Apostle Church and Triple Church followed in Hanover.

Palaces

In castles, there was a similar enthusiasm for the medieval among architects and builders as with churches. The castles were built on the basis of former, fortified castles and therefore received their typical design means such as battlements or towers. After preserved castle ruins were restored in a first phase, it came from the middle of the 19th century. Century to a lively activity at new castle buildings, in which the Hanover School was also used. She undergone a change in the coming decades: The architects went away from symmetrical, cubic-regular castles, towards asymmetrically constructed systems. While the Marienburg designed by Conrad Wilhelm Hase still showed a quite orderly appearance, Julius Rasch designed Imbshausen Castle as the first irregular castle according to the principles of the Hanover School. In addition to the two mentioned, Edwin Oppler, Christoph Hehl, Karl Börgemann, Adelbert Hotzen and other architects also worked as castle builders.

Town Halls and Government Buildings

Town halls have always embodied civil liberty and independence, which the buildings until the 20th century. century was the most important and representative civil buildings.The rapidly growing urban population in the course of industrialization ensured that administrative tasks also increased significantly. For the town halls, this meant numerous conversions, extensions or new buildings. However, these construction projects were not exclusively based on practical aspects, the town halls also fulfilled an important social function. They showed architecturally how proud and important a city had become.

About the town hall in Hanover, Kokkelink judges that it had an exemplary character for other cities in northern Germany.The medieval building was expanded and restored several times between 1839 and 1891. This phase of transformation had already begun in 1826, when the city director Wilhelm Rumann planned to have the old town hall demolished.According to his idea, a larger new building was to be built in the same place, which would have offered twice as much usable space as the old building. The design came from the city builder August Andreae, who provided for a four-storey house in round arch style. However, the project met with massive resistance from the citizens and the Bürgervorher College, so Rumann moved away from the execution. Instead, he successfully applied for the new construction of an internal "prisoner house"as an extension of the town hall. Andreae designed it from 1839 to 1841 based on the round arch style, but also equipped the tract with previously largely unknown style elements. Andreae developed a design language via brick reliefs, two-storey glare arcades, segment arches and lisenens, which was later taken up by the Hanover School.[After the prison house, the court wing followed along Köblinger Straße until 1850, for which the former pharmacy wing had to be demolished beforehand. Andreae carried out the facade of the court wing with "North Italian-Romanesque"shapes, which is why the part of the building was quickly nicknamed "Dogenpalast". In the following twenty years, there were protests again that prevented the further construction of new tracts. It was not until the end of 1863 that the magistrate commissioned the Hanoverian Association of Architects and Engineers to develop a restoration and use concept for the town hall. The discussions about the concept lasted a good ten years before Conrad Wilhelm Hase was appointed to draw up plans for restoration in 1875. Hase's designs were received by the magistrate, who decided to execute them at the beginning of 1877. Hase's plans provided for "the medieval state with the continuation of all subsequent additions"; during execution, the plans were only slightly changed by adding a few stairs and partitions. The restoration work for the exterior of the market wing could be completed in 1879, while the work inside continued until 1882. At the time of the inauguration, a general meeting of German architects and engineers took place in Hanover. Their participants praised in Hase's designs the "conceptual uniformity, the all-encompassing breakdown of the inside and exterior" and "the total restoration of the Gothic state."According to Günther Kokkelink, Hase was very cautious at the town hall in Hanover, as he had demanded with his motto "Keeping at the old."The "honority of the old monument" was more important to rabbits than the "subjective artistic ambitions". As the last part of the town hall, the new "Hase wing" to Karmarschstraße was built in 1890–91.The wing facing southeast became necessary after the Grupenstraße had previously been created. This, now called Karmarschstraße, led as a breakthrough across the old town to ensure a fast connection of the train station with the western city of Linden. For representation purposes, Hase gave the wing another floor and a middle gable. At its end faces, the wing received superangular fial gable, which flanks the town hall to the southeast in an almost symmetrical way.

The Hanoverian case subsequently had an "animating effect on other northwest German cities with Gothic town halls": Urban planners now often preferred overall restorations over selective partial restorations. Just a few months after the inauguration in Hanover, Heinrich Gerber designed the plan for a complete restoration of Göttingen City Hall. This was realized between 1883 and 1886. In Hildesheim, Gustav Schwartz led the comprehensive restoration of the town hall, carried out from 1883 to 1887. In Lübeck, it was Adolf Schwiening who presented a plan for the complete restoration of the local town hall in 1883. All three - Gerber, Schwartz and Schwiening - had learned from Hase.

Museums

Most museums during the neo-Gothic construction phase were created in the 1880s and 1890s, by which art historian Volker Plagemann describes as a time of state museum construction.[This time was preceded by the phases of princely (1815–1848) and bourgeois (until 1870) museum construction. From the latter, the principles of a "monumental external appearance"of the houses still had an effect until the turn of the century. According to this, the museums received representative buildings as an important educational institution. For many construction projects, the Dresden Gemäldegalerie, built in 1847-55 by Gottfried Semper, was considered a model. In addition to classicist art temples, her appearance in the Renaissance style became the standard in museum building. The Hanover School could therefore only prevail for such construction tasks in its strongholds.

Schools and Gymnasiums

Triggered by industrialization, it occurred in the second half of the 19th century. century to a strong increase in the urban population.[In addition to other challenges in the field of housing construction and infrastructure, numerous school buildings also had to be rebuilt within a few years. In Hanover, the number of pupils in elementary schools rose from around 7,500 in 1876 to just under 27,000 in 1905. Different types of schools were created for different requirements: grammar schools and reform high schools, higher daughter schools, secondary schools, civic schools, elementary schools, blind and deaf-mute schools, schools for members of religious minorities and auxiliary schools. Within the school types, there was a hierarchy in which high schools and secondary schools were among the top rank and were therefore carried out most elaborately in terms of design. The principle of the Hannover School to use the brick unplastered saved the city administration costs.

There were no pre-modern role models in the 19th century. The architects therefore initially derived their designs from meeting rooms such as those used in churches or schools. The emerging gymnastics movement under the "turn father" Friedrich Ludwig Jahn served for leisure activities, but was also intended to get the Germans in shape for military conflicts. The logo of the movement, the Turnerkreuz, first appeared in 1846. It is composed of four "F" who stand for the motto of the movement "fresh, pious, cheerful, free".Many gymnasiums of the Hannover School received the cross as an ornament.[Wilhelm Hauers and Wilhelm Schultz built the gym in the Hanover Maschstraße. Created in 1864/65, it is probably the oldest surviving building in the Südstadt district. It is also one of the halls that were built very early for a gymnastics's association. The construction is very wide with 15 window axes. Originally, it comprised only two floors, but was then increased in repairing the damage of the Second World War. A special feature of the hall is its out-centered entrance risalite with triangular gable and attached filagonal gable. Inside, the supporting structure can also be seen, it consists of supports connected with pointed arches. According to the monument topographic atlas of 1983, the gym is of great importance for Hanover despite the subsequent conversion.

Hospitals and Monasteries

Church hospitals already existed in the Middle Ages, which were mostly built near the city center. In addition, there were "seven houses"(such as plague houses), which were created outside the city to avoid the spread of epidemics. In the 19th In the 19th century, hospital buildings for specific needs were built for the first time after scientific findings on the requirements for certain therapies had been developed. At that time, the concept of pavilions also became popular. In addition to the general hospitals, specialist clinics, such as birthplaces or children's hospitals, were also created.

For mentally ill people, King George V had two smaller state madhouses built around 1860.200 people were to be accommodated in the two houses, one in Osnabrück and one in Göttingen. Adolf Funk and Julius Rasch designed the Göttingen facility as a closed, symmetrical facility, in the center of which a garden was created. Most of the buildings were designed by the architects in a round arch style or in an "even more classicist neo-Gothic", as the building historian Günther Kokkelink puts it.[At the chapel, Rasch opted for the Hanover School - probably quite consciously, as is suspected in literature. Within the complex, the chapel was of particular importance: it was to resemble a normal village church with its "beautiful vaults" and thus contribute to the relief of physical suffering. A mere prayer room inside the building was considered insufficient to give comfort and strength. Since not enough of the same building material could be obtained for the entire plant, Rasch had to mix different types of stone, including sandstone, tuff stone, brick and yellow facing bricks.

Christoph Hehl blinded the Clementine House with yellow bricks, created from 1885 to 1887 in Hannover-List. With contrasting bricks in red, he revisited the idea of brick polychromy, which Conrad Wilhelm Hase had already applied to today's Künstlerhaus in 1856.[The preserved, two-and-a-half-storey building is now the oldest part of the hospital. The building is free and slightly moved back from the adjacent Lützerodestraße, with an orientation from east to west and the show side to the south. The facade is symmetrically constructed with three gable ricals. The middle one of it takes up the entrance and is therefore slightly wider and higher than the lateral risalites.[

In Heiligengeistraße in Hanover, the Hospital St. Spirit (Holy Spirit Monastery) built.Karl Börgemann chose design elements of the "classic" Hanover School. A south facade of 76 m in length was created. She received a middle risalite with a "pruificent"overangle fial gable, as well as two side risalites that indicate the rear side wings.[In the horizontal, the facade is divided by differently colored brick ribbons, and the cornices also vary. The third floor is highlighted from the lower floors, here double windows and glare arcades alternate. The medium risalite also carries dark green glazed tiles, which additionally structure it.The building of the Heiligengeiststift is one of the "most impressive"civil buildings of the Hannoversche Schule that have been preserved.

Villas and Single-family Houses

Villa Willmer was the "most powerful and largest"villa, built according to the principles of the "classic" Hanover School. Karl Börgemann designed the building built in 1884-86 for Hanoverian brick producer Friedrich Willmer. The house was located in Hanover-Waldhausen and at the time cost the huge sum of around 2 million. Goldmark and was about three times the size of usual villas. Willmer had brought wealth thanks to the Hanover School, the brick buildings that were built everywhere generated large sales. The villa had an angular floor plan and contained about 75 rooms, over 50 of which were located on the three living floors. In its size and design, the house resembled a castle rather than a villa. The popular nickname Tränenburg probably stems from the fact that Willmer treated his workers badly and shed many "tears" for the construction of the house. The building survived the Second World War almost unscathed. Nevertheless, despite far-reaching citizen protests, it was demolished in 1971 for an ultimately never implemented new construction project.

In Kassel, the so-called Villa Glitzerburg (actually Villa Wedekind) built by Wilhelm Lüer and Conrad Wilhelm Hase was a highly regarded building built in the style of the Hanover School. At the time, it was the largest private residence in Kassel.

At the turn of the century, land prices often increased to such an extent that single-family houses were combined.An outstanding example of this is the residence of the architect Karl Mohrmann in Hanover, described in the sheets for architecture and handicrafts in 1913 as "one of the most successful and significant [residential houses] of the newer Hanoverian construction". Contrary to the usual design principles of the Hannover School, Mohrmann chose a rectangular fial or pillar gable for his house, into which he integrated painted plaster fields. Such a motif comes more from Gothic buildings on the Baltic Sea than from the surroundings of Hanover. Mohrmann emphasized the corner of the house with a "powerful"tower, which had an observation deck reinforced by battlements.

A few years before the house of Mohrmann, around 1890, a group of villas was created at the western end of Hanover's Callinstraße. The confluence with Nienburger Straße is highlighted with the left tower of the double villa no. 48/50. The towers with their pointed helmets form a typical feature of the Hanover School, as well as the decorative gable.

Rectories

Rectories are a special form of residential building. The art historian Günther Kokkelink says that they were in the 19th century. century often with its own design claim.[The neo-Gothic has proven to be particularly suitable for this construction task. Their formal language of medieval sacred buildings was very suitable for underlining the purpose of the rectory. In the countryside, the rectories often received outbuildings for stables or as sheds, usually taken back creatively. End of the 19th Century often emerged in "painian group"ensembles of churches and rectories.

Ludwig Frühling designed the rectory for the Marktkirchengemeinde am Marktplatz in Hanover in 1883–84. The house relates to the nearby town hall, which Hase had renovated a few years earlier, via its three large finial gables.

The rectory of the Hanoverian Christ Church comes from Karl Börgemann. In addition to the apartments for several families, the large, "imposing"corner building also houses rooms for other church-relevant purposes, such as a library or meeting rooms. The house, built in 1905/06, has a corner tower and high stair gables, the facade is equipped with green glazed bricks. As usual for late buildings of the Hannover School, the house is provided with larger areas and shows less small details. After war destruction, it was rebuilt in its old form between 1946 and 1948.

Mixed-Use Apartment Buildings

Hase and Adelbert Hotzen also introduced the Hanover School to apartment buildings in the 1860s. At first, the Gothic style was well received by nobles, in addition, some wealthy and art-interested citizens were enthusiastic about it. The brick architecture was perceived as "German" at the time, unlike plaster buildings, these buildings seemed to be "honest."Some freelance architects advertised their skills by building "nexotic 'model houses'"on their own account, which they then sold ready for occupancy. While villas were built on extensive, park-like plots, the residential buildings had to make do in less elegant residential areas with small plots. Here, the effect of a building depended directly on the surrounding houses, which is why an architect often built several contiguous plots of land. According to Kokkelink, this achieved a uniform style and thus a greater urban planning effect. Corner houses often received a tower and were thus able to have an even greater effect than terraced houses.[These striking corner buildings were often used as residential and commercial buildings. Although development costs were incurred for two roads at the same time, the additional use as a commercial building increased the return.Advances in the brick industry caused falling prices of building materials in the 1870s and 1880s, brick buildings became affordable for more and more builders. The argument that brick facades do not require special care proved to be particularly sales-promoting, unlike plaster buildings. Increasingly, tenement houses were also increasingly built according to the principles of the Hannover School. This was especially true for the rapidly growing districts of Hanover, the Oststadt and the Nordstadt, as well as the then still independent city of Linden.

Factories, Railway Stations, and other Industrial Buildings

The strict representatives of the neo-Gothic styles tried to transfer the design features of medieval architecture not only to churches, town halls and villas, but also to shape other civil buildings. This also extended to buildings where practicality was in the foreground, such as factories, train stations, warehouses or barracks. While many aesthetic teachings failed to extend their formal language to such construction tasks, the Hanover School was widely used in civil engineering. At the end of the 19th In the 19th century, it had made it to the standard of style in northern and western Germany in industrial construction.[

Many decades before the advent of the Hanover School, in the end of the 18th century. century, a need for multi-storey factory buildings arose. These should accommodate large work rooms.The multi-storey structure was necessary to transmit the force vertically via transmissions. The factories were often designed inside as a skeleton building, which was covered with masonry on the outside. For a long time, the skeleton consisted of a wooden construction, against which initially only slowly more expensive cast iron constructions prevailed. However, iron supporting structures offered the great advantage of being fireproof. Where the cross members of the skeleton lay on, the outer walls usually had to be reinforced by lisens, which gave the outer facade a rhythmic structure. The outwardly readable inner construction was entirely in line with the neo-Gothic styles, to which the "constructive truth" was considered the basic principle. Schinkel's Building Academy in Berlin, which with its pronounced brick lilys in the construction axes, proved to be a model for other architectural currents, proved to be forward-looking here. In Hanover, the mechanical weaving mill was the first modern type factory to receive an external design according to Hanoverian round arch style. The building designed by Heinrich Ludwig Debo was built in 1857-58. New to him were the two tower-like head buildings. In addition to the staircases, they also contained ancillary and supervisory rooms and were clearly detached from the production wing in terms of design. Mechanical weaving thus anticipated one of the basic ideas of the Hannover School. Their supporters later demanded that the building sections determined by floor plan requirements should be "effectively" grouped. In addition, it should be possible to read from the outside what purpose the individual part of the building serves.

In the early days of industrialization, manufacturers had often had their production buildings run as pure utility buildings that had only a minimum of decorations.The systems, which were often expanded in rapid succession, often only received a certain unity because the buildings were built in a round arch style. It was considered an economical construction method in which architectural decoration could be easily achieved by an appropriate arrangement of the bricks. At that time, the importance of a factory was almost exclusively measured by its spatial extent and not by its aesthetic appearance. Only in the second half of the 19th century. In the 19th century, a change of heart returned, factories increasingly received a representative shell. After the founding of the Reich, the round arch style was finally increasingly replaced by the Hannoversche Schule in industrial construction.

The stations of the rapidly growing railway network experienced a similar development to the factories. Here, too, the architects abandoned the round arch style and moved towards the Gothic revival, whose design language expressed the pride of the operators.

Expansion Outside of Lower Saxony

The architects of the 19th century trained at the Polytechnic School in Hanover and the teaching opinions there spread throughout northern Germany and beyond. One example was Flensburg, which was still under Danish rule until 1864. Here Johannes Otzen and Alexander Wilhelm Prale created a series of brick buildings in the sense of the Hannover School, some of which still shape the cityscape today.[The guiding principles advocated by Conrad Wilhelm Hase found their way to Norway, where Balthazar Lange and Peter Andreas Blix designed small station buildings in accordance with neo-Gothic ideals. The Hanoverian influences also extended to North America, and as in Norway, it also affected railway architecture there. The German architect Wilhelm Lorenz was at the service of a Pennsylvanian railway company and thus had an influence on its station architecture. However, his designs followed the principles of the Rundbogenstil more than those of the "classic" Hanover School.

Flensburg

Within Germany, the Hannover School spread north to the Danish border. In Flensburg, which was ruled by Prussia after the German-Danish War in 1864, Johannes Otzen and especially Alexander Wilhelm Prale provided that the cityscape was minted. Both Otzen and Prale had learned from Conrad Wilhelm Hase in Hanover.

Johannes Otzen designed a residential building for the wholesale merchant Christian Nicolai Hansen in 1869, which was "one of the first major construction projects in Flensburg, now Prussia" by Eiko Wenzel.It was built on Große Straße No. 77 near Nordermarkt.The christen Hansen House received a three-axle risalit with step-step fial gable. Green and brown glazed shape stones, a polychrome facade and a colored slate roof ensured that the building became a kind of "performance show"for the new style. For Wenceslas, in addition to an architectural-historical significance, the house also has a contemporary historical relevance, because it shows how the bourgeoisie turns towards the German-Prussian state.[

Alexander Wilhelm Prale began his work in Flensburg near Otzen, under whose supervision he carried out two new church tower buildings as an architect or construction manager from 1878: for the church of St. Marien am Nordermarkt and for the church of St. Nikolai at Südermarkt. The two towers shaped the silhouette of the city from 1880 with their neo-Gothic appearance and their colored slate coverings. After completing the two projects, Prale received further orders for church construction tasks. From 1880 to 1883, for example, he worked on the reconstruction and expansion of the Deaconesses Institute, a church hospital. For the representative facade to the valley town, Prale designed a yellow brick facade, structured by strips of red bricks. Wenceslas attested to the building's "significant urban planning effect"for its multi-storey and despite its small dimensions. However, the neo-Gothic exterior architecture completely disappeared due to later extensions and conversions.During his time in Flensburg, Prale also created civil buildings. As early as 1880, he built for J. A. Olsen a commercial building on Südermarkt (not received). The house was in a visual relationship with the recently completed tower of the Nikolaikirche. With its four floors, it became significantly larger than the surrounding medieval development, for Wenceslas a "sensitive scale break". The house thus embodied the "new metropolitan claim of Prussian Flensburg" and also demonstrated the "economic optimism" of the time.[The facade held Prale in red bricks; he designed the window openings differently from floor to floor: the ground floor got pointed-arched windows (later replaced by a large shop window), while on the first floor the windows of the right part of the facade were combined in pairs with segment arches. The pointed-arched windows of the second floor sat again in individual blind niches with a clover leaf arch closure upwards. The windows of the third floor were pointedly closed and edged in circumferential "form stone bulges", closed downwards with sole benches. A special feature of Prales were cleaned surfaces in the glare niches on which tendrils or functions of the house were displayed. Together with layers of glaze bricks and the colored slate roof, these plaster surfaces gave the Olsen House a "strongly polychrome facade image". In the next few years, more residential and commercial buildings of Prale followed. These include the Kontor- und Wohnhaus Schiffbrücke No. 21 (1880/81), the residential and commercial building Schiffbrücke No. 24 (1882) and the shipping company office and residential building Schiffbrückstraße No. 8 (1883).[In his pastoral buildings for the St. Nicholas community at Südermarkt (1900) and the St. John's community at Johanniskirchhof (1903/04), Prale took up the type of corner villa. This had become a popular solution of the Hannover School since the 1870s.

Alexander Wilhelm Prale was in Flensburg at the end of the 19th century. Century ascended to a leading architect whose building quality was only achieved by Johannes Otzen's projects in the opinion of Wenceslas. Even after 1900, Prale remained firmly attached to the neo-Gothic style in the sacred building and subsequently could no longer win larger orders. In secular cultivation, he slowly turned to the emerging Art Nouveau around 1902. However, Prale failed to further develop the brick construction he represented until the onset of homeland security architecture, comments Wenzel.

Norway

The Norwegian architects Balthazar Lange (1854-1937) and Peter Andreas Blix (1831-1901) worked in the railway construction of their home country in the 1880s. Both had studied under Conrad Wilhelm Hase at the Polytechnic School in Hanover. The guiding principles of the Hannover School had a great influence on the architecture of Norway since the late 1850s, because many Norwegian architects had been trained by Hase. In Christiania (Oslo) there was a separate group of supporters.

Train station architecture by Balthazar Lange for the Jarlsberg route: Classicist buildings for larger cities (Larvik, left, location) and regionally-traditional buildings for rural stops in the sense of neo-Gothicism (Skoppum, right, location)

In an essay published in 2011, Mari Hvattum discusses the development of Norwegian railway architecture in the 19th century. Century. The architects Lange and Blix created the station buildings of the so-called "Jarlsberg route" along the southeastern coast of Norway between the cities of Drammen and Skien.While the stations of larger cities received buildings in a rather ordinary neoclassical style, the rural stops were provided with wooden buildings whose style varied and was characterized by very diverse influences. Due to this different design, the contrast between the small and large stations was considerable. According to Hvattum, the wooden appearance of rural railway stations was seen as a reflection of the regional environment - Nordic - while the urban stations reflected a European - classicist - character. The Jarlsberg route thus illustrates a cultural debate that the 19th century. century determined. For the German romantics starting from Johann Gottfried Herder, the north is associated with "anti-classical" motifs that have been regarded as "un-uncut" and "natural". In contrast, there would be the "classical south."These two opposites could also be reflected in architecture, in which neoclassicism and neo-Gothicism formed the two camps. The neo-Gothic stood for an expression of "spontaneity" and "viviality" here. The rural railway stations in their traditional wooden construction are completely in line with Hase's doctrines. He regarded medieval architecture as a Nordic style: a regionally credible alternative to the "rigid" and "artificial" classicism of the south.

North America

The influences of the Hanover School reached as far as North America. Immigrant German architects and engineers applied the principles of teaching primarily in railway construction. This mainly concerned the US state of Pennsylvania, where most Germans emigrated.

The architect Wilhelm Lorenz (1826-1884), trained at the Hanover Polytechnic University, played a special role.[He had studied with Ernst Ebeling from 1844 to 1846. Like many graduates of the time, Lorenz also suffered from a lame construction activity in the course of the German Revolution. As a result, he left Germany to work for the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad railway company in the United States. At that time, there was no academic training for architecture in America, which is why German architects and engineers were gladly accessed. Lorenz was a special feature in Philadelphia because most of his immigrant colleagues came from southern Germany. According to art historian Michael J. Lewis suggest many signs that Lorenz was "the most important representative of the Hannover School in America". In 1860 Lorenz rose to become a senior engineer for a secondary line of the Reading Railway Company and as such also designed the railway structures. Until 1879, it was still common for functional buildings to be constructed by engineers, while freelance architects designed buildings with a representative character, but mostly limited to the facade.The orientation at the Hanover School was first shown at Norristown station. For this purpose, the American architect Joseph Hoxie presented a revised design in 1858, which showed a "finely structured building structure", structured by a "net of slender lisens and console cornices". According to Lewis, the building gained a character over it that was more reminiscent of the "lively surfaces of medieval architecture" than of the quiet forms of classicism. Lorenz, who had become chief engineer of the entire railway company in 1871, caused a growing German influence. Around 1873, he designed a station in the "strict" round arch style for the Reading junction. In his arrangement in the middle of a three-sided property surrounded by tracks, Lewis the station appears more as a "sign central station"than through or terminal station. However, Lorenz had not followed the principles of the "classic" Hanover School with his design, for which he had left Hanover too early. For cost reasons, the Reading train station was ultimately created in a simplified barracks style. At the end of the 1870s, the architectural view of the railway company changed. In order to set itself apart from a competing company, the stations should now be "dreastly highlighted by architectural means." For this purpose, the American architect Frank Furness was employed in 1879, which probably made Lorenz's influence dwindle. A little later, the railway company got into financial difficulties, while Lorenz fell seriously ill and finally died in 1884.

Demise and legacy

The architectural influences of the Hanover School did not disappear abruptly, but sounded slowly for decades.In the late phase of neo-Gothicism, among other things, the administration building of Westinghouse AG on Goetheplatz in Hanover (not preserved) was built. The brick building designed by Karl Börgemann around 1900 had "an increased tendency to monumentalization"compared to previous buildings of the Hannover School. The Biermann commercial building at Herrenstraße No. 8 in Hanover comes from Alfred Sasse. Built in 1905/06, the house has a facade made of tuff stone and black Oeynhaus facing stones, which are grouted white. However, the "powerful and noble"facade also has many small-scale details that are in the sense of the Hanover School: The window dimension and the tower-like elevated staircase can still be recognized by the "filigree broken"gables of the staircase were not preserved.[At the residential and commercial building on Voßstraße, corner Jakobistraße, built in 1913, contemporary publications already read about a revival of brick building in Hanover. Wilhelm Türnau designed the "well-proportioned"corner semi-detached house. It has vertical outline elements in the gable fields, bay windows and a facade structure over two floors. Although the original roof structure was lost in the Second World War and was only restored in a simplified way, according to the building historian Günther Kokkelink, the house still sets a good example of the transition of the Hanover School to modernity. Further examples of foothills of the Hannover School are the Gertrud-Marien-Heim in Hannover-Linden Mitte and the extension of the Hanoverian biscuit factory Bahlsen in Hannover-List.[

The Anzeiger-Hochhaus, built in 1927–28 in the center of Hanover, is also in the tradition of the Hanover School, with its overangle finials. The architect Fritz Höger was a leading representative of brick expressionism, which otherwise used a little overarchal. The overarchal fials also sound in the "strict vertical division"of the Franzius Institute. This research building for the Hanover University of Technology was built in 1928-31 under the supervision of Franz Erich Kassbaum.

Later Developments

After 1945, many of the buildings that had survived the Second World War, especially in Hanover, received little appreciation. Günther Kokkelink notes that in devotion to everything that seemed modern, the architecture of historicism had met with a general rejection. Representative buildings of well-known architects have been rebuilt in a simplified form or demolished completely, often to be replaced by "all-world architecture".[Eiko Wenzel stated in an essay published in 1999 that monument preservation is not yet able to improve the artistic quality of the buildings from the late 19th century in many places. century to present convincingly.[The reason is that monument preservation still lacks the evaluation criteria for this. The contempt for this stylistic era has its origin in the Heimatschutzstil, which rejected historicism. The Heimatschutz movement, like historicism, borrowed from historical role models.

Redevelopment of Hanover after the Second World War

In the summer of 1948, Rudolf Hillebrecht was elected city planning councilor of Hanover.He was considered a representative of modernity and was a great supporter of Walter Gropius. He could not derive much from the architecture training at the Hanover University of Technology at the time and criticized it as "poor" and "not exactly complex" during his studies.[He did not join the Bauhütte for this reason. For the redesign of Hanover after the Second World War, Hillebrecht attached decisive importance to the aspects of "structure and transport": "The image of the modern city center is significantly influenced, perhaps determined by these two factors."The redesign should not start from "aesthetic ideas", but should be determined by a "meaningful economic use of the different districts". Hillebrecht tried to transform the city in a car-friendly way. For this purpose, he had tangential roads built (the expressways) and transformed inner city squares into "traffic turbines", including the Kröpcke and the Aegidientorplatz. Between the back of the station and Raschplatz, traffic routes were built on two levels.

In order to preserve old building fabric during the transformation, the Association of German Architects tried in 1964 to persuade the city to a statute for the protection of historical buildings. There was no monument protection law at that time. In order not to affect his plans, Hillebrecht prevented such a statute from becoming binding.buildings from the 19th century Century received little appreciation from him, Hillebrecht attested to them "nothing more than having made bonds in all stylistic epochs of European architecture". He also talks about "embarrassing eclecticism of culturally weak decades". Hermann Deckert, at the time state conservator and previously rector of the Hanover University of Technology, shared Hillebrecht's views. In his inventory The preservation of monuments in the province of Hanover, he had already spoken disparagingly about the houses on Karmarschstraße in 1936 and called them "badges of the Gründerzeit" The houses on the north side of the market square, including the rectory of the Marktkirche, were "liedy 'Gothic' buildings" for Deckert In the following years, many buildings from the 19th century were built. century demolished. Among other things, the rectory of the Kreuzkirche (Paul Rowald, 1892) and the remains of Conrad Wilhelm Hase's house (hare, 1859) were affected by the buildings of Hanover School. The Ratsgymnasium on Georgsplatz (Ludwig Droste, 1854), built in a round arch style, had to give way to a new building of Nord/LB (Hanns Dustmann, 1957).

Demolition of the Villa Willmer

Even after the demolitions of the 1950s, the monument preservation interest in buildings of the Hannoversche Schule remained partly low. Exemplary stands for this is the Villa Willmer ("Tränenburg") in Hanover-Waldhausen, the demolition of which accompanied a great public interest in 1971.[The castle-like house had only been slightly damaged during the war and was inhabited until the beginning of 1971. The heirs of brick manufacturer Friedrich Willmer had sold the villa with land to a housing company last year. The company planned to have a total of 150 new apartments built on the property, for which the villa was to give way. Since Rudolf Hillebrecht had previously prevented the initiatives for monument protection, the city had no way of intervening against the demolition. After the new construction plans became public in the Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung at the end of 1970, there were protests. In a public advertisement, citizens called on the city administration to prevent "the purposeless destruction of this precious architectural monument". Among the undersigned were many architects, members of the Hanover University of Technology and other people in (formerly) high offices.[The Lower Saxony Chamber of Architects organized a demonstration, and various experts also advocated the preservation of the building.[The city administration did not go into the offers of the housing association to either leave the property including the villa to the city in exchange or to preserve the villa and to build the rest of the property more densely. An initiative that wanted to operate the house as an art and cultural center also failed. At a meeting of the building committee in April 1971, the city council finally decided to grant the demolition permit. This was pronounced at the end of August 1971 and the house was then demolished immediately.[

Only at the end of the 20th Century, a change began, monument preservation interest and urban tourism led to increased efforts to preserve the existing buildings.Nevertheless, demolitions have also recently occurred: For example, a residential building was demolished for the construction of the specialist court center in Hanover,in Lehrte, the administrative building of a former printing house in Gartenstraße disappeared.

Reception

Hase insisted that the structure of the building and the building materials used, preferably local, remain visible to the viewer.

Hase's students were not only senior engineering officials and well-known architects, but they also taught at trade schools, for example in Eckernförde, Hamburg, and Nienburg. At the first major North German building trade school in Holzminden, there was a group of Hase's admirers in the teachers' association Kunstclubb ("Art club") who sought to spread the Hanoverian school in the 1860s.

Selected representatives

- Ludwig Droste (1814–1875)

- Conrad Wilhelm Hase (1818–1902)

- Hermann Hunaeus (1812–1893)

- Franz Andreas Meyer (1837–1901)

- Edwin Oppler (1831–1880)

- Julius Rasch (1830–1887)

- Christian Heinrich Tramm (1819–1861)

Elements of style

- Adherence to medieval brick Gothic style

- Preference for local building materials (wood, brick, sandstone)

- Brick wall facades with brick ornaments

- German frieze, dentil, and glazed bricks as decorative elements

- Crow-stepped gable on the verge and segmental arch lintels above windows and doors (round arch style)

- Absence of exterior plaster, decorative sculptures and colored surfaces

- Recognizability of the brick building shell

Examples

- Artists' House, Hanover, 1853–1856, Conrad Wilhelm Hase

- Marienburg Castle, Schulenburg (Pattensen), 1857–1867, Conrad Wilhelm Hase and Edwin Oppler

- Church of Christ, Hanover, 1859–1864, Conrad Wilhelm Hase

- Jewish sermon hall, Hanover, 1861–1864, Edwin Oppler

- Synagogue, Hanover, 1863–1870, Edwin Oppler

- St. Luke's Church, Lauenau, about 1875

- Old City Hall, Hanover, restoration from 1878 to 1882, Conrad Wilhelm Hase

- Church of the Apostles, Hanover, 1880–1884, expansion from 1889 to 1891, Conrad Wilhelm Hase

- Speicherstadt, Hamburg, about 1890

- Courthouse, Lübeck, 1894–1896, Adolf Schwiening

- Community house and parsonage, Church of Christ, Hanover, 1905–1906, Karl Börgemann

- Gym of the Gymnastics Club, Hanover, 1864–65, W. Hauers, W. Schultz

References

- Günther Kokkelink, Monika Lemke-Kokkelink: Baukunst in Norddeutschland. Architektur und Kunsthandwerk der Hannoverschen Schule 1850–1900. Schlütersche, Hannover 1998, ISBN 3-87706-538-4.

- Günther Kokkelink, Eberhard G. Neumann: Vorwort. In: Sabine Baumgart, Jürgen Knotz: Die Bauwerke der Eisenbahn in Niedersachsen. Teil 1: Bestandsaufnahme, Katalog des gesammelten Materials. Forschungsbericht des Instituts für Bau- und Kunstgeschichte der Universität Hannover. Selbstverlag, Hannover 1983.

- Friedrich Lindau: Hannover. Wiederaufbau und Zerstörung. Die Stadt im Umgang mit ihrer bauhistorischen Identität. Zweite, überarbeitete Auflage. Schlütersche, Hannover 2000, ISBN 3-87706-659-3.

- Theodor Unger (Hrsg.): Hannover 1882: Ein Führer durch die Stadt und ihre Bauten. Nachdruck des historischen Buches aus dem Klindworth's Verlag. Europäischer Hochschulverlag, Bremen 2011, ISBN 978-3-86741-493-7.

- Sid Auffarth, Wolfgang Pietsch: Die Universität Hannover: ihre Bauten, ihre Gärten, ihre Planungsgeschichte. Imhof, Petersberg 2003, ISBN 3-935590-90-3. Fußnote 23 auf S. 128.

- Ulrike Faber-Hermann: Bürgerlicher Wohnbau des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts in Minden. Lit, Münster / Hamburg / London 2000, zugleich veränderte Dissertation, Universität Minden, 1989, ISBN 3-8258-4369-6.

- Sabine Baumgart, Jürgen Knotz: Die Bauwerke der Eisenbahn in Niedersachsen. Teil 1: Bestandsaufnahme, Katalog des gesammelten Materials. Forschungsbericht des Instituts für Bau- und Kunstgeschichte der Universität Hannover. Selbstverlag, Hannover 1983.

- Günther Kokkelink, Eberhard G. Neumann: Vorwort. In: Sabine Baumgart, Jürgen Knotz: Die Bauwerke der Eisenbahn in Niedersachsen. Teil 1: Bestandsaufnahme, Katalog des gesammelten Materials. Forschungsbericht des Instituts für Bau- und Kunstgeschichte der Universität Hannover. Selbstverlag, Hannover 1983. Die beiden Autoren zitieren aus einer Festschrift, die anlässlich des 150-jährigen Bestehens der Universität Hannover erschien. Für die Festschrift hatte Kokkelink einen Beitrag über Conrad Wilhelm Hase verfasst.

Bibliography

- Gustav Schönermark: Die Architektur der Hannoverschen Schule. (The architecture of the Hanover School). 7 vols., Hanover, 1888-95.

- Günther Kokkelink, Monika Lemke Kokkelink: Baukunst in Norddeutschland. Architektur und Kunsthandwerk der Hannoverschen Schule 1850-1900 (Architecture in Northern Germany. Architecture and handicrafts of the Hanover school from 1850 to 1900). Schlütersche, Hanover 1998.

- Saskia Rohde: Im Zeichen der Hannoverschen Architekturschule: Der Architekt Edwin Oppler (1831-1880) und seine schlesischen Bauten (Under the banner of the Hanover School of Architecture: The architect Edwin Oppler (1831-1880) and his Silesian buildings). In Hannoversche Geschichtsblätter (Hanoverian History Pages), Hanover, 2000, Hahnsche Buchhandlung, ISBN 3-7752-5954-6.

- Klaus Mlynek: Hannoversche Architekturschule (Hanoverian school of architecture). In: Stadtlexikon Hannover (Encyclopedia of the city of Hanover), p. 257.