Harry Raymond Eastlack

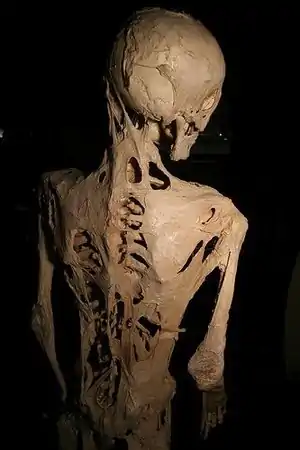

Harry Raymond Eastlack, Jr. (17 November 1933 – 11 November 1973) was the subject of the most recognized case of FOP (fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva) from the 20th century. His case is also particularly acknowledged, by scientists and researchers, for his contribution to medical advancement. After suffering from a rare, disabling, and currently incurable genetic disease, Eastlack decided to have his skeleton and medical history donated to the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in support of FOP research. His skeleton is one of the few FOP-presenting, fully articulated ones in existence, and it has proved valuable to the study of the disease.[1]

Harry Raymond Eastlack, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Skeleton of Eastlack at the Mütter Museum in the College of Physicians of Philadelphia | |

| Born | Harry Raymond Eastlack, Jr. November 17, 1933 |

| Died | November 11, 1973 (aged 39) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Resting place | The Mütter Museum |

| Known for | Suffering from and supporting the study of Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva |

As is characteristic of FOP patients, Eastlack did not demonstrate any possible sign of a disease at birth except for a malformation of the big toes. At the time it was not recognized as the first clinical sign of FOP.[2] It was not until 1937 when the first heterotopic ossification symptom surfaced. By the time of his death, Eastlack's skeleton bore sheets of bone along the vertebrae, which fused to and locked his skull, and branches of bone along his limbs, which immobilized his shoulders, elbows, hips, and knees.[3] He died in Philadelphia of bronchial pneumonia six days before his 40th birthday.[1]

Early life

Birth

Harry Eastlack was born on November 17, 1933 at 10:24 AM in the Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia. There are no reports of any difficulties during his delivery, though there was the observation of a minor congenital malformation. The noted malformation was his congenital bilateral hallux valgus, oftentimes referred to as a bunion.[1]

Family

Harry Raymond Eastlack, Jr. was son to Helen Florence Brown and Harry Raymond Eastlack. They were both 40 years of age at the time of his birth. His father, Harry, worked in the railroads under engineering management, while his mother was a housewife. They resided in 5745 Haddington Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and at the time of Harry's birth they already had a daughter by the name of Helene. Harry was closest to his mother, Helen. She would walk him to and from school, as well as bake for him at home. His sister, Helene, later became a music teacher and remained in Philadelphia.[1]

Childhood

Records suggest that his childhood was an active and happy one. His pastimes consisted of listening to music on the radio or records at home. Eastlack would also enjoy reading, playing with his sister, and going to the movies. Additionally, a seat was exclusively reserved for him at the center of the seventh row in Hamilton Theater, a musical theater, in Philadelphia. It has been claimed that ushers would not let anyone else sit there, as the spot was spacious enough to later allow Eastlack to stretch his immobile leg.[1]

Diagnosis

While heterotopic bone growth can begin spontaneously in FOP patients, Eastlack, like most patients, first experienced a triggered proliferation due to an illness or injury. [4] He was about four years old, playing with Helene, his sister, outdoors. A car hit his leg, injuring his left femur.[1] He was taken to the hospital where his leg was put in a cast before returning home. The fracture never set properly, and when the cast was removed months later, his leg was painfully swollen with a high amount of inflammation. No further action was taken and shortly after Eastlack began to experience his first set of abnormal bone growths. His hips and knees had become difficult to move.[5] When he was taken to the hospital with this concern, the doctor took X-rays in which the bony deposits on his thigh muscles were revealed.[3] The doctors were not able to diagnose his condition having seen this, and it continued to progress in the anatomically characteristic manner that FOP does. Eastlack soon suffered flare-ups along his back, neck, and chest.

In attempts to diagnose and treat Eastlack's condition, the doctors ordered biopsies and performed a total of 11 surgical procedures to remove excess and heterotopic ossification, such as that on his thigh muscles. However, Eastlack's condition was aggravated by such procedures and the bone plates returned thicker and more predominant.[1] It was 1938, the year after the incident, when he was finally diagnosed with Myositis ossificans progressiva, which is now known as Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP).[3]

Later life and FOP progression

Unaware of the consequences of surgery on an FOP patient, the physician admitted Eastlack for hip surgery in 1941 which caused further physical restriction. Over time Eastlack became more and more immobilized as more joints became fused and newly formed sheets or strings of bone calcified his limbs. In 1944 he was readmitted for a study which confirmed that the calcified smooth muscles, tendons, and ligaments had indeed become mature bone. The ossification along his vertebrae and other anatomical parts that Eastlack would suffer in the next 29 years ultimately fused him into a permanently bowed position.[6]

Eastlack's case of FOP progressed at a more rapid rate due to the number of intrusive surgeries he underwent. In 1948, at the age of 15, his jaw had become fused so he could no longer eat solid food and had to speak through clenched teeth.[7] At a young age he faced difficulty sitting down, as well. His hips were one of the first anatomical parts to become immobilized due to heterotopic ossification. Soon, bone formed across his upper arms and extended onto his sternum, tying his arms to his breast. Sheets of bone spread along his back and ribbons of bone extended from there to his skull, inhibiting proper head movement. The new bone growths throughout the years also caused juts of bone to form on his pelvis and thighs, and it caused both of his feet to become clubbed.[6] One year he accidentally bumped his buttocks into a radiator, and this resulted in a bruise wherein the smooth tissue was destroyed and gave way to newly formed bone.[5] Ultimately, the only mobility that Eastlack had left was that of his eyes, lips, and tongue.

As the disease progressed, Eastlack struggled more with routine movement and self-care. At first it was his mother, Helen, who would assist and care for him. However, by the time Eastlack reached about 20 years old, his mother was too feeble to continue. He was then taken to a nursing home in Philadelphia, The Inglis House for the Incurables, which is now simply known as the Inglis House.[1]

Death

Eastlack died at the Inglis House for the Incurables—a care home dedicated to attending low income, physically disabled individuals.[8] As he approached the later stages of his life, he required assistance to stand and used a cane to be able to shuffle. During his time there, his right leg broke and is said to have healed at an odd angle. Consequently, he spent years bedridden and developed bronchial pneumonia from the physical inactivity. Due to the ossification on his ribs, his lungs could not expand well and this inhibited his ability to cough.[6] Near the time of his death, Eastlack told his sister, Helene, that he desired to donate his body and medical records to research, so that the disease may be further investigated and understood.[1] On November 11, 1973, just six days shy of his 40th birthday, he died of pneumonia.[6]

Medical contributions

Eastlack's home, Philadelphia, has become a center for FOP research with much of it concentrated at the University of Pennsylvania. With his skeleton on display, doctors and professors alike lead students to the Mütter Museum to observe the result of the rare disorder in person. Since surgeries and examinations of FOP patients exacerbate the condition, the ability to study Eastlack's skeleton has been significant for research. For example, in 2006, University of Pennsylvania's team of researchers and scientists led by Frederick Kaplan was able to distinguish the particular gene responsible for the disease, the ACVR1 gene. It is said that Eastlack's skeleton was a useful reference for this medical discovery.[9] The International FOP Association is also granted Eastlack's skeleton for displaying and informational purposes in medical meetings and international FOP symposia, which physicians, researchers, and patients attend.[1] For example, over 43 families were recorded to have attended a two-day symposium hosted in Philadelphia in October 1995 to listen to orthopedic surgeons and physicians discuss the details of FOP. During this symposium, Eastlack's skeleton was used as a reference.[10] After seeing his skeleton at this event, fellow FOP patient Carol Orzel decided to also donate her body to the museum. She died in February 2018, and in February 2019, her skeleton was put on display next to his.[11]

Mentions in culture

In the 2009 film inspired by Edgar Allan Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart", Tell-Tale, Eastlack is mentioned and referred to as Harry Erlich. The mention occurs in a scene where characters are in a museum, and a skeleton is referred to.[12] The scene provides some genuine facts, such as how Eastlack's skeleton does not require any wiring or glue to be held together in the museum because the fused bones hold it all in one piece.[13]

References

- Kaplan, Frederick S. (2013-10-01). "The skeleton in the closet". Gene. 528 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.022. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 4586120. PMID 23810943.

- "Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) - Teaching Learners with Special Needs - MSSE.704.01 - (2135) - RIT Wiki". wiki.rit.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (2017-09-01). "Mütter Museum American Sign Language Tour: Harry Eastlack". YouTube. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- "Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Heine, Steven J. (2017). DNA is not Destiny: The Remarkable, Completely Misunderstood Relationship Between you and your Genes. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0393244083.

- "Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "Memento Mutter". memento.muttermuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "History | Inglis". www.inglis.org. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (2017-09-01), Mütter Museum American Sign Language Tour: Harry Eastlack, retrieved 2018-10-07

- Kelly, Evelyn B. (2013). Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, California 93116: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 274. ISBN 978-0313387135.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - McCullough, Marie (28 February 2019). "New Mutter Museum exhibit grants final wish for woman who turned to bone". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- "The Tell-Tale Heart (2016) Movie Script | SS". Springfield! Springfield!. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- "The Eastlack Skeleton". The Biologist. 61 (4): 46.

External links

- "Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP)". The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library. Digitized by the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Retrieved November 28, 2018.