Bunion

A bunion, also known as hallux valgus, is a deformity of the joint connecting the big toe to the foot.[2] The big toe often bends towards the other toes and the joint becomes red and painful.[2] The onset of bunions is typically gradual.[2] Complications may include bursitis or arthritis.[2]

| Bunion | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hallux abducto valgus, hallux valgus[1] |

| |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, Podiatry |

| Symptoms | Prominent, red, and painful joint at the base of the big toe[2] |

| Complications | Bursitis, arthritis[2] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[2] |

| Causes | Unclear[1] |

| Risk factors | Wearing overly tight shoes, high-heeled shoes, family history, rheumatoid arthritis[2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, X-rays[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Osteoarthritis, Freiberg's disease, hallux rigidus, Morton's neuroma[4] |

| Treatment | Proper shoes, orthotics, NSAIDs, surgery[2] |

| Frequency | ~23% of adults[1] |

The exact cause is unclear.[1] Proposed factors include wearing overly tight shoes, high-heeled shoes, family history, and rheumatoid arthritis.[2][3] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and supported by X-rays.[2] A similar condition of the little toe is referred to as a bunionette.[2]

Treatment may include proper shoes, orthotics, or NSAIDs.[2] If this is not effective for improving symptoms, surgery may be performed.[2] It affects about 23% of adults.[1] Females are affected more often than males.[2] Usual age of onset is between 20 and 50 years old.[1] The condition also becomes more common with age.[1] It was first clearly described in 1870.[1] Archaeologists have found a high incidence of bunions in skeletons from 14th- and 15th-century England, coinciding with a fashion for pointy shoes.[5][6]

Signs and symptoms

.png.webp)

Symptoms may include irritation of the skin around the bunion, and blisters may form more easily at the site. Pain may be worse when walking.

Bunions can lead to difficulties finding properly fitting footwear and may force a person to buy a larger size shoe to accommodate the width of the bunion. If the bunion deformity becomes severe enough, the foot can hurt in different places even without the constriction of shoes. It is then considered as being a mechanical function problem of the forefoot.

Cause

The exact cause is unclear.[1] It may be due to a combination of internal and external causes.[7] Proposed factors include wearing overly tight shoes, high-heeled shoes, family history [2][3] and rheumatoid arthritis. The American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons states that footwear only worsens a problem caused by genetics.[8]

Excessive pronation of the foot causes increased pressure on the inside of the big toe that can result in a deformation of the medial capsular structures of the joint, subsequently increasing the risk of developing bunions.[7][9]

Pathophysiology

The bump itself is partly due to the swollen bursal sac or an osseous (bony) anomaly on the metatarsophalangeal joint. The larger part of the bump is a normal part of the head of the first metatarsal bone that has tilted sideways to stick out at its distal (far) end (metatarsus primus varus).

Bunions are commonly associated with a deviated position of the big toe toward the second toe, and the deviation in the angle between the first and second metatarsal bones of the foot. The small sesamoid bones found beneath the first metatarsal (which help the flexor tendon bend the big toe downwards) may also become deviated over time as the first metatarsal bone drifts away from its normal position. Osteoarthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint, diminished and/or altered range of motion, and discomfort with pressure applied to the bump or with motion of the joint, may all accompany bunion development. Atop of the first metatarsal head either medially or dorso-medially, there can also arise a bursa that when inflamed (bursitis), can be the most painful aspect of the process.

Diagnosis

Bunion can be diagnosed and analyzed with a simple x-ray, which should be taken with the weight on the foot.[10] The hallux valgus angle (HVA) is the angle between the long axes of the proximal phalanx and the first metatarsal bone of the big toe. It is considered abnormal if greater than 15–18°.[11] The following HV angles can also be used to grade the severity of hallux valgus:[12]

- Mild: 15–20°

- Moderate: 21–39°

- Severe: ≥ 40°

The intermetatarsal angle (IMA) is the angle between the longitudinal axes of the first and second metatarsal bones, and is normally less than 9°.[11] The IM angle can also grade the severity of hallux valgus as:[12]

- Mild: 9–11°

- Moderate: 12–17°

- Severe: ≥ 18°

Treatment

Conservative treatment for bunions include changes in footwear, the use of orthotics (accommodative padding and shielding), rest, ice, and pain medications such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These treatments address symptoms but do not correct the actual deformity.[13] If the discomfort persists and is severe or when aesthetic correction of the deformity is desired, surgical correction by an orthopedic surgeon or a podiatric surgeon may be necessary.

Orthotics

Orthotics are splints or regulators while conservative measures include various footwear like toe spacers, valgus splints, and bunion shields. Toe spacers seem to be effective in reducing pain, but there is not evidence that any of these techniques reduces the physical deformity. There are a variety of available orthotics including off-the-shelf commercial products and custom-molded orthotics, which may be prescribed medical devices.[14]

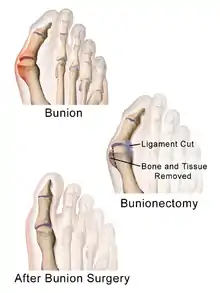

Surgery

Procedures are designed and chosen to correct a variety of pathologies that may be associated with the bunion. For instance, procedures may address some combination of:

- removing the abnormal bony enlargement of the first metatarsal,

- realigning the first metatarsal bone relative to the adjacent metatarsal bone,

- straightening the great toe relative to the first metatarsal and adjacent toes,

- realigning the cartilaginous surfaces of the great toe joint,

- addressing arthritic changes associated with the great toe joint,

- repositioning the sesamoid bones beneath the first metatarsal bone,

- shortening, lengthening, raising, or lowering the first metatarsal bone,

- correcting any abnormal bowing or misalignment within the great toe,

- connecting two parallel long bones side by side by syndesmosis procedure

At present there are many different bunion surgeries for different effects. The age, health, lifestyle and activity level of the patient may also play a role in the choice of procedure.

Traditional bunion surgery can be performed under local, spinal or general anesthetic. A person who has undergone bunion surgery can expect a 6- to 8-week recovery period during which crutches are usually required to aid mobility. An orthopedic cast is much less common today as newer, more stable procedures and better forms of fixation (stabilizing the bone with screws and other hardware) are used. Hardware may even include absorbable pins that perform their function and are then broken down by the body over the course of months. After recovery long term stiffness or limited range of motion may occur in some patients. Visible or limited scarring may also occur for patients.

References

- Dayton, Paul D. (2017). Evidence-Based Bunion Surgery: A Critical Examination of Current and Emerging Concepts and Techniques. Springer. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9783319603155.

- "Bunions". OrthoInfo - AAOS. February 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Barnish, MS; Barnish, J (13 January 2016). "High-heeled shoes and musculoskeletal injuries: a narrative systematic review". BMJ Open. 6 (1): e010053. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010053. PMC 4735171. PMID 26769789.

- Ferri, Fred F. (2010). Ferri's Differential Diagnosis E-Book: A Practical Guide to the Differential Diagnosis of Symptoms, Signs, and Clinical Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 323. ISBN 978-0323081634.

- Dittmar, Jenna; Mitchell, Piers (11 June 2021). "Fashion for pointy shoes unleashed a wave of bunions in medieval England". The Conversation. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- Dittmar, Jenna M.; Mitchell, Piers D.; Cessford, Craig; Inskip, Sarah A.; Robb, John E. (2021-06-11). "Fancy shoes and painful feet: Hallux valgus and fracture risk in medieval Cambridge, England". International Journal of Paleopathology. 35: 90–100. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2021.04.012. ISSN 1879-9817. PMC 8631459. PMID 34120868.

- Brukner, Peter (2010). Clinical sports medicine (3 ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 667. ISBN 9780070278998.

- "Bunions (Hallux Abducto Valgus)". Footphysicians.com. 2009-12-18. Archived from the original on 2011-12-08. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- Chou, Loretta B. (19 June 2015). "Disorders of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint". The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 28 (7): 32–45. doi:10.3810/psm.2000.07.1075. PMID 20086649. S2CID 21529142.

- Page 533 in: Sam W. Wiesel, John N. Delahay (2007). Essentials of Orthopedic Surgery (3 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387383286.

- Rebecca Cerrato, Nicholas Cheney. "Hallux Valgus". American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society. Archived from the original on 2016-12-30. Retrieved 2016-12-30. Last reviewed June 2015

- Piqué-Vidal, Carlos; Vila, Joan (2009). "A geometric analysis of hallux valgus: correlation with clinical assessment of severity". Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/1757-1146-2-15. ISSN 1757-1146. PMC 2694774. PMID 19442286.

- Hecht, PJ; Lin, TJ (March 2014). "Hallux valgus". Medical Clinics of North America (Review). 98 (2): 227–32. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2013.10.007. PMID 24559871.

- Park, CH; Chang, MC (May 2019). "Forefoot disorders and conservative treatment". Yeungnam University Journal of Medicine. 36 (2): 92–98. doi:10.12701/yujm.2019.00185. PMC 6784640. PMID 31620619. (see Figure Two for images of orthotics)

External links

- Textbook of Hallux Valgus and Forefoot Surgery, links to complete text in PDF files