Hastings, Minnesota

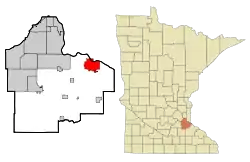

Hastings (/ˈheɪstɪŋz/ HAY-stingz)[6] is a city mostly in Dakota County, Minnesota, of which it is the county seat, with a portion in Washington County, Minnesota, United States.[7] It is near the confluence of the Mississippi, Vermillion, and St. Croix Rivers. The population was 22,154 at the 2020 census.[3] It is named for the first elected governor of Minnesota, Henry Hastings Sibley.[8]

Hastings | |

|---|---|

City Hall, originally the Dakota County Courthouse | |

| |

| Coordinates: 44°45′12″N 92°52′48″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| Counties | Dakota, Washington |

| Founded | 1853 |

| Incorporated | March 7, 1857 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mary Fasbender |

| Area | |

| • City | 11.20 sq mi (29.02 km2) |

| • Land | 10.35 sq mi (26.81 km2) |

| • Water | 0.85 sq mi (2.20 km2) |

| Elevation | 801 ft (244 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 22,154 |

| • Estimate (2021)[4] | 21,925 |

| • Density | 2,139.86/sq mi (826.20/km2) |

| • Metro | 3,693,729 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 55033 |

| Area code | 651 |

| FIPS code | 27-27530[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2394320[2] |

| Website | hastingsmn.gov |

The advantages of Hastings's location that led to its original growth are that it is well-drained, provides a good riverboat port, and is close to a hydropower resource at the falls of the Vermillion River. Other sites closer to the river confluence are either too swampy (Dakota County) or too hilly (Washington County and Pierce County, Wisconsin).

U.S. Highway 61 and Minnesota State Highways 55 and 316 are three of Hastings's main routes.

History

In the winter of 1820, a military detachment from Fort Snelling settled the area around Hastings to guard a blocked shipment of supplies. Lieutenant William G. Oliver camped in an area that came to be known as Oliver's Grove; in 1833 a trading post was opened there.[9] After the Treaty of Mendota of 1851 opened the area for white settlement, Oliver's Grove was surveyed and incorporated as a city in 1857, a year before Minnesota's admission to the Union. The same year, Hastings was named the county seat of Dakota County. The name "Hastings" was drawn out of a hat from suggestions placed in it by several of the original founders.[10]

In the mid-19th century, Hastings, Prescott, Wisconsin, and the adjacent township of Nininger were areas of tremendous land speculation. Ignatius L. Donnelly promoted the area as a potential "New Chicago." The Panic of 1857 put an end to this dream. The speculation and panic caused the cities' growth to be less than expected given their location at the confluence of two significant rivers; today, their combined population is approximately 25,000, and all that remains of Nininger is a few building ruins.

Hastings has Minnesota's second-oldest surviving county courthouse (after Washington County Courthouse, Stillwater), finished in 1871 at a cost of $63,000. The county administration began moving to a new facility in 1974, and in 1989 the City of Hastings purchased the old building. It was rededicated in 1993 as City Hall.

.jpg.webp)

In 1895 a spiral bridge was built over the Mississippi River, designed to slow down horse-drawn traffic as it entered downtown. The novel design became a tourist attraction, but the bridge was demolished in 1951 because it could not handle modern vehicles. The 1951 bridge was itself demolished and its replacement opened in 2013.

In 1930, the Army Corps of Engineers completed Lock and Dam No. 2 at Hastings, part of the canal lock systems on the Mississippi that stretch from Minneapolis to St. Louis. Lock and Dam No. 2 is the site of the nation's first commercial, federally licensed hydrokinetic power facility, a partnership between the City of Hastings and Hydro Green Energy, LLC of Westmont, Illinois.

Fasbender Clinic, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, is a city landmark.

Railroads

Hastings's name was affixed to two major Minnesota railroads, the Hastings & Dakota Railway and the Stillwater & Hastings Railway.

In 1867 civic leaders William LeDuc, John Meloy, Stephen Gardner, E. D. Allen, and P. Van Auken—with financial backing from investors John B Alley, Oliver Ames, William Ames and Peter Butler—incorporated the Hastings & Dakota Railway with the goal to "cross the Rocky Mountains and meet the Pacific Ocean". In the 1870s the H&D was completed from Hastings to the South Dakota border at Ortonville. During this time, the H&D became part of the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad (Milwaukee Road) and became known as the H&D Division of the Milwaukee Road. The H&D also built the famous "Lake Street Depression" in Minneapolis, which gave the H&D two districts around Minneapolis and St. Paul: the south district from Hastings to Cologne via Chaska, and the north district from Hastings to Cologne via St. Paul/Minneapolis. The H&D never made it to the Pacific on its own, but the H&D Division became the mainline of the Milwaukee's Coast Extension to Seattle, which the Milwaukee completed in 1909.

In 1880 a new branch line, the Stillwater & Hastings, was built between the two cities. It funneled logging and agriculture products from Stillwater to Hastings, allowing Hastings to become an important railroad switching hub. In 1882 the Milwaukee Road gained control of the S&H and operated it as a profitable branch line. The Milwaukee abandoned the S&H line in 1979, after 99 years of service.

The north H&D district remains intact from Minneapolis to Ortonville—except for the Lake Street Depression—and is operated by the Twin Cities & Western Railroad from Minneapolis to Hanley Falls and by BNSF Railway between Hanley Falls and Ortonville. Nearly all of the south H&D district was abandoned over time, with the last section between Shakopee and Cologne abandoned in the early 1970s. The Canadian Pacific Railway spur from downtown Hastings to the Ardent Mills mill atop Vermillion Falls is all that remains of the south H&D district. The old H&D trestle over the Vermillion River at Hastings—which was replaced four different times—is now part of a bicycle path. The H&D bridge over the Minnesota River at Chaska remained until 1995, when the Army Corps of Engineers removed it as the Chaska levees were rebuilt.

Canadian Pacific Railway now operates the former Milwaukee mainline through town as well as the Ardent Mills spur.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 11.18 square miles (28.96 km2); 10.24 square miles (26.52 km2) is land and 0.94 square miles (2.43 km2) is water.[11] The Mississippi River forms most of Hastings's northern border, while the Vermillion River flows through the southern part of town, over a falls adjacent to a ConAgra grain elevator. Bluffs lie along the northern shore of the Mississippi and there is a gorge surrounding the Vermillion below the falls. Hastings is home to two small lakes, Lake Rebecca and Lake Isabel. Both drain into the Mississippi River. The northeast corner of town, an area of soggy marshland and flood plain for the Mississippi and Vermillion Rivers, is known as "Cow Town".

Hastings is on the Mississippi side of the confluence with the St. Croix River, so that the St. Croix is "across" the Mississippi River. Prescott, Wisconsin is on the Wisconsin side of the confluence.

| Climate data for Hastings, Minnesota | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F | 21 | 28 | 39 | 55 | 69 | 78 | 82 | 80 | 71 | 58 | 40 | 26 | 54 |

| Average low °F | 2 | 9 | 22 | 36 | 48 | 57 | 62 | 60 | 51 | 39 | 24 | 10 | 35 |

| Average precipitation inches | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 30.1 |

| Average high °C | −6 | −2 | 4 | 13 | 21 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 22 | 14 | 4 | −3 | 12 |

| Average low °C | −17 | −13 | −6 | 2 | 9 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 11 | 4 | −4 | −12 | 2 |

| Average precipitation mm | 23 | 15 | 43 | 71 | 86 | 100 | 110 | 100 | 79 | 56 | 51 | 20 | 760 |

| Source: [12] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 1,653 | — | |

| 1870 | 3,458 | 109.2% | |

| 1880 | 3,809 | 10.2% | |

| 1890 | 3,705 | −2.7% | |

| 1900 | 3,811 | 2.9% | |

| 1910 | 3,983 | 4.5% | |

| 1920 | 4,571 | 14.8% | |

| 1930 | 5,086 | 11.3% | |

| 1940 | 5,662 | 11.3% | |

| 1950 | 6,560 | 15.9% | |

| 1960 | 8,965 | 36.7% | |

| 1970 | 12,195 | 36.0% | |

| 1980 | 12,827 | 5.2% | |

| 1990 | 15,445 | 20.4% | |

| 2000 | 18,204 | 17.9% | |

| 2010 | 22,172 | 21.8% | |

| 2020 | 22,154 | −0.1% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 21,925 | [4] | −1.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 2020 Census[3] | |||

2010 census

As of the census of 2010, there were 22,172 people, 8,735 households, and 5,802 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,165.2 inhabitants per square mile (836.0/km2). There were 9,222 housing units at an average density of 900.6 per square mile (347.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.1% White, 1.6% African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.8% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.6% of the population.

There were 8,735 households, of which 34.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.0% were married couples living together, 11.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 33.6% were non-families. 27.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 2.98.

The median age in the city was 37.5 years. 24.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 27.4% were from 25 to 44; 26.3% were from 45 to 64; and 13.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.2% male and 50.8% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 18,204 people, 6,642 households, and 4,722 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,798.2 inhabitants per square mile (694.3/km2). There were 6,758 housing units at an average density of 667.6 per square mile (257.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.16% White, 0.43% African American, 0.38% Native American, 0.64% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.36% from other races, and 0.99% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.14% of the population.

There were 6,642 households, out of which 37.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.8% were married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.9% were non-families. 22.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.64 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.3% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 30.6% from 25 to 44, 21.5% from 45 to 64, and 11.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $53,145, and the median income for a family was $61,093. Males had a median income of $41,267 versus $27,973 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,075. About 2.1% of families and 4.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.4% of those under age 18 and 9.8% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Sites of interest

- Alexis Bailly Vineyard

- East Second Street Commercial Historic District

- Hastings High School

- Hastings Sand Coulee Scientific and Natural Area

- LeDuc Historic Estate

- Lock and Dam No. 2

- Ramsey Mill Ruins

- Spring Lake Park Reserve

- Vermillion Falls Park

- West Second Street Residential Historic District

Government

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 50.4% 6,701 | 46.8% 6,224 | 2.8% 375 |

| 2016 | 49.6% 5,946 | 40.6% 4,869 | 9.8% 1,177 |

| 2012 | 47.7% 5,773 | 49.7% 6,021 | 2.6% 322 |

| 2008 | 45.4% 5,535 | 52.1% 6,353 | 2.5% 313 |

| 2004 | 48.0% 5,490 | 50.7% 5,795 | 1.3% 147 |

| 2000 | 43.9% 3,930 | 49.5% 4,432 | 6.6% 597 |

| 1996 | 31.1% 2,297 | 55.9% 4,133 | 13.0% 967 |

| 1992 | 30.3% 2,426 | 44.6% 3,570 | 25.1% 2,001 |

| 1988 | 44.8% 3,059 | 55.2% 3,770 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1984 | 46.8% 3,008 | 53.2% 3,424 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1980 | 36.1% 2,319 | 54.5% 3,505 | 9.4% 603 |

| 1976 | 35.6% 2,096 | 62.0% 3,649 | 2.4% 141 |

| 1968 | 36.5% 1,486 | 60.0% 2,441 | 3.5% 141 |

| 1964 | 25.8% 1,074 | 74.0% 3.083 | 0.2% 8 |

| 1960 | 36.9% 1,338 | 62.9% 2,365 | 0.2% 7 |

Education

Hastings Public Schools operates public schools.

| Hastings, Minnesota Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Name | Grades Served | Location | Date Established | Picture | Mascot |

| Minnesota Central University | Post Secondary | 8th & Sibley Street | 1857-1867 (purchased for the Hastings Public School in 1867 and torn down in 1899) | ||

| Everett School | Primary and Intermediate | 2nd & Franklin Street | 1866-1927 | Puppy Dogs | |

| Irving School | High School | 8th & Sibley Street | 1867-1899 (Formerly Minnesota Central University, fire destroyed the building around 1899) | ||

| Hastings Central School | High School | 8th & Sibley Street | 1899-1961 | ||

| Hastings Junior-Senior High School | High School | 10th & Vermillion Street | 1961-1999 (Several additions were made and later became Hastings Middle School) | Raiders (18th Century Knight on a Horse) | |

| Tilden Elementary School | Elementary School | 3rd & River Street | ?-closed in 2009 (Building currently used as a community center) | Tigers | |

| Cooper Elementary School | Elementary School | 17th & Vermillion Street | 1959-closed in 2009 (Building currently used as a community preschool) | Comets | |

| Hiawatha Elementary School | Elementary School | 10th & Vermillion, then moved to 10th & Tyler | ?-1961 | ||

| John F. Kennedy Elementary School | Elementary School | 10th & Tyler Street | 1962-current | Cougars | |

| Pinecrest Elementary School | Elementary School | 13th & Pine Street | ?-current | Panthers | |

| Hastings Senior High School, new | High School | 11th & Pine Street | 1972-current (currently used as Hastings Middle School) | Raiders (raccoon) | |

| Christa McAulliffe Elementary School | Elementary School | 12th & Pleasant Street | 1988-current | Eagles (Challengers) | |

| Hastings Senior High School, new | High School | General Sieben Drive and Featherstone Road | 2000-current | Raiders (pirate) | |

Infrastructure

Transportation

![]() Hastings's busiest route is U.S. Highway 61, which in Hastings is also known as Vermillion Street. Highway 61 is a four-lane thoroughfare that cuts north–south through eastern Hastings; it continues north out of Hastings over the Mississippi via the Hastings High Bridge to Cottage Grove and Saint Paul, and south to Red Wing. The bridge carries 32,000 vehicles per day and is Minnesota's busiest two-lane bridge. Construction started on a four-lane bridge in late 2010 and was completed in 2013.[29][30]

Hastings's busiest route is U.S. Highway 61, which in Hastings is also known as Vermillion Street. Highway 61 is a four-lane thoroughfare that cuts north–south through eastern Hastings; it continues north out of Hastings over the Mississippi via the Hastings High Bridge to Cottage Grove and Saint Paul, and south to Red Wing. The bridge carries 32,000 vehicles per day and is Minnesota's busiest two-lane bridge. Construction started on a four-lane bridge in late 2010 and was completed in 2013.[29][30]

![]() Hastings's other major route is Minnesota State Highway 55, the main east–west roadway. It is also a four-lane highway that enters the city from the west and cuts through the middle of town where it eventually comes to an end at Highway 61. 55 is a major commuter route for residents of Hastings, taking them northwest to Eagan and Minneapolis.

Hastings's other major route is Minnesota State Highway 55, the main east–west roadway. It is also a four-lane highway that enters the city from the west and cuts through the middle of town where it eventually comes to an end at Highway 61. 55 is a major commuter route for residents of Hastings, taking them northwest to Eagan and Minneapolis.

![]() Highway 316 is a 10-mile highway that starts at Highway 61 in southern Hastings and heads southeast to Welch Township. It acts as a more direct shortcut between two points of Highway 61. 316 is just west of the Mississippi. Highways 316 and 61 are both part of the Great River Road. 316 is also known as Red Wing Boulevard and Polk Avenue at various points on its route.

Highway 316 is a 10-mile highway that starts at Highway 61 in southern Hastings and heads southeast to Welch Township. It acts as a more direct shortcut between two points of Highway 61. 316 is just west of the Mississippi. Highways 316 and 61 are both part of the Great River Road. 316 is also known as Red Wing Boulevard and Polk Avenue at various points on its route.

![]() Highway 291 (Minnesota Veterans Home Highway) is a one-mile roadway in eastern Hastings. It is also known as East 18th Street and Le Duc Drive, and crosses the Vermillion River.

Highway 291 (Minnesota Veterans Home Highway) is a one-mile roadway in eastern Hastings. It is also known as East 18th Street and Le Duc Drive, and crosses the Vermillion River.

Other routes that lead into Hastings are Dakota County Roads 42 (northwest side of town), 46 (southwest), 47 (southwest) and 54 (east).

Hastings is not served by the Metro Transit public transportation bus routes, but preliminary studies are underway to bring commuter rail to Hastings via the Red Rock Corridor. Amtrak trains pass through, but do not stop in, Hastings (passengers must go to St. Paul or Red Wing to board).

The Mississippi is a major thoroughfare for barges, which are helped upstream by Lock and Dam No. 2 in northwest Hastings. There are several access points to the Mississippi for private watercraft.

Notable people

- Jackie Biskupski, mayor of Salt Lake City and former Utah state legislator

- Taylor Chorney, professional hockey player for the Washington Capitals

- George Conzemius, Minnesota state senator and educator

- MaryJanice Davidson, author

- Gil Dobie, college football coach

- Mark Doten, novelist[31]

- Aaron Fox, hockey player and coach

- Thomas K. Gibson, Wisconsin state senator

- Mark Steven Johnson, film director and writer

- Craig Kilborn, comedian and television personality

- Larry LaCoursiere, professional boxer

- Clara Mairs, painter and printmaker

- Dan Peltier, baseball player for the Texas Rangers

- Terry Redlin, painter

- Harry Sieben, former speaker of the Minnesota House of Representatives

- Mike Sieben, former member in the Minnesota House of Representatives

- Katie Sieben, former member in the Minnesota Senate

- Derek Stepan, professional hockey player for the Carolina Hurricanes

- Jeff Taffe, professional hockey player

- Dean Talafous, former NHL hockey player[32]

- Ben Utecht, professional football player and singer

- Daniel Welch, ice hockey forward who notably went five-hole in the high school state hockey championship in the final seconds

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hastings, Minnesota

- "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Minnesota Pronunciation Guide". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 152.

- Minnesota; a state guide. New York: Viking Press. 1938. p. 298. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Upham, Warren (1920). Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 165.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- "Daily Normals of Hastings, Minnesota". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved April 12, 2006.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- "Minnesota Secretary of State - 2020 Precinct Results Spreadsheet".

- "Minnesota Secretary of State - 2016 Precinct Results Spreadsheet".

- "Minnesota Secretary of State - 2012 Precinct Results Spreadsheet".

- "Minnesota Secretary of State - 2008 Precinct Results Spreadsheet".

- "Minnesota Secretary of State - 2004 Precinct Results Spreadsheet".

- "Minnesota Secretary of State - 2000 Precinct Results Spreadsheet".

- (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1996-11-05-g-sec.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1992-11-03-g-sec.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1988-11-08-g-sec.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1984-11-06-g-sec.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1980-11-04-g-sec.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1976-11-02-g-sec.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1968-11-05-g-man.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1964-11-03-g-man.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - (PDF) https://www.lrl.mn.gov/archive/sessions/electionresults/1960-11-08-g-man.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - MPR: Hastings bridge downgraded

- Hastings Bridge Project Home Archived October 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Hastings High School graduate writes first novel

- 1973 NHL Amateur Draft - Dean Talafous

18. Cochran Recovery Services Faces an Uncertain Future in Hastings. https://www.hastingsstargazette.com/news/4592133-cochran-recovery-services-faces-uncertain-future-hastings