Prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to the state, either a warship of its navy or a privateer vessel commissioned by the state. Prize money was most frequently awarded for the capture of enemy ships or of cargoes belonging to an enemy in time of war, either arrested in port at the outbreak of war or captured during the war in international waters or other waters not the territorial waters of a neutral state. Goods carried in neutral ships that are classed as contraband, being shipped to enemy-controlled territory and liable to be useful to it for making war, were also liable to be taken as prizes, but non-contraband goods belonging to neutrals were not. Claims for the award of prize money were usually heard in a prize court, which had to adjudicate the claim and condemn the prize before any distribution of cash or goods could be made to the captors.

Other cases in which prize money has been awarded include prize money for the capture of pirate ships, slave ships after the abolition of the slave trade and ships trading in breach of the Navigation Acts, none of which required a state of war to exist. Similar monetary awards include military salvage, the recapture of ships captured by an enemy before an enemy prize court has declared them to be valid prizes (after such ships have been condemned, they are treated as enemy ships), and payments termed gun money, head money or bounty, distributed to men serving in a state warship that captured or destroyed an armed enemy ship. The amount payable depended at first on the number of guns the enemy carried, but later on the complement of the defeated ship.

Certain captures made by armies, called booty of war, were distinct from naval prize because, unlike awards under naval prize legislation, the award of booty was only made for a specific capture, often the storming of a city; the award did not set a precedent for other military captures in the same war, and did not require adjudication by a prize court. When the British army and navy acted together, it was normal for instructions to say how any prizes and booty should be shared, and the shares allocated. In this case, combined naval and military force to be dealt with under naval prize law rules.

Although prize law still exists, the payment of prize money to privateers ceased in practice during the second half of the 19th century and prize money for naval personnel was abolished by those maritime states that had provided it at various times in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

Origins

The two roots of prize law and the consequent distribution of prize money are the mediaeval maritime codes, such as the Consolato Del Mare and Rolls of Oleron, which codified the customary laws that reserved legal rights over certain property found or captured at sea, in harbour or on the shore for the rulers of maritime states,[1] and the 16th and 17th century formulation of international law by jurists such as Hugo Grotius.[2] These jurists considered that only the state could authorise war, and that goods captured from an enemy in war belong as of right to its monarch. However, it was customary for the state to reward those who that assisted in making such captures by granting them part of the proceeds.[3]

In various 17th century states, the crown retained from one-tenth to one-fifth of the value of ships and cargoes taken by privateers but up to half of the value of those captured by the state's navy. Grotius also recorded the practices that, for a prize to be effective, the ship must either be brought to port or retained for 24 hours, and that no distribution of prize money or goods could made without due court authorisation.[4]

Most European maritime states, and other maritime states that adopted laws based on European models, had codes of prize law based on the above principles that allowed for monetary rewards for captures. However, details of prize money law and practice are known for relatively few of these. They include English rules from the 17th century, which formed the basis for the rules for Great Britain and the United Kingdom in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, those of France from the 17th to 20th centuries, the Dutch Republic, mainly for the 17th century, and the United States for the 18th and 19th centuries.[5] The smaller navies of maritime states such as Denmark and Sweden, had little chance of gaining prize money because they had few opportunities to capture enemy ships in wartime, both because, after the Great Northern War, they were rarely involved in naval wars and, when they were, their fleets were much weaker than their major opponents.[6]

Booty of war

Booty of war, also termed spoils of war is the movable property of an enemy state or its subjects which can be used for warlike purposes, in particular its soldiers' arms and equipment, captured on land, as opposed to prize which is hostile property captured at sea. It is legally the property of the victorious state, but all or part of it (or its value) may be granted to the troops that capture it.[7] In British practice, although the Crown may grant booty and to specify its distribution, this was done by a special proclamation relating to a specific capture which did not set a precedent, not a general measure dealing with all captures made during a war, as were naval prize acts.[8] Instances of it being granted include the Siege of Seringapatam, 1799, the capture of Bordeaux, 1814 and the Siege of Delhi, 1857.[7] Although the United States and France had allowed their soldiers to profit from booty on a basis similar to Britain, they abolished the practice in 1899 and 1901 respectively.[9] The Third Geneva Convention now only allows the arms, military equipment and military documents of prisoners of war to be seized and prohibits the award of booty.

England to 1707

The Crown of England had, from medieval times, legal rights over certain property found or captured at sea or found on the shore. These included the rights to shipwrecks, ships found abandoned at the sea, flotsam, jetsam, lagan and derelict, enemy ships and goods found in English ports or captured at sea in wartime and goods taken from pirates. At first, these were collectively known as Droits of the Crown, but after the creation the office of the High Admiral, later the Lord High Admiral, of England in the early 15th century, they were known as Droits of Admiralty, as the Crown granted these rights, and legal jurisdiction the property specified in them, to the Lord Admiral. This jurisdiction ceased in 1702, but the name Droits of Admiralty remained in use.[10]

Early prize law made little distinction between financial rewards made to officers and men of the Royal Navy and to privateers (civilians authorised to attack enemy shipping by letters of marque issued by the Crown), as the former did not exist as a permanent force until the 16th century. Mediaeval rulers had no administrative mechanism to adjudicate prizes or collect the royal share.[11] The first Admiralty Court in England with responsibility for prize and prize money issues was created in 1483 and subordinate Vice-Admiralty courts were later set up in British colonies. Appeal from the Court of Admiralty was to the Privy Council. As the rights over enemy ships or goods are legally prerogatives of the Crown, there are few English or British statues that deal with naval prize money, other than the prize acts issued at the start of each war, authorising the Crown to issue orders or proclamations dealing with prize money, and these acts affirm rather than limit the Crown's rights.[12]

From Elizabethan times, the Crown insisted that the validity of prizes and their value had to be determined by royal courts, and that it should retain a portion of their value. In some cases, an English ship failing to bring a prize for adjudication was confiscated. Beyond this, it was left to the discretion of the Crown, guided by custom, as to what should be allocated to those taking prizes, and how that prize money should be allocated between the owners, the officers and the crew.[13] Generally, the Crown retained one-tenth of the value of prizes captured by privateers. By ancient custom, the common seamen, but not the officers, of navy vessels had the right of free pillage, the seizure of the enemy crew's personal possessions and any goods not stored in the hold.[14] The Commonwealth attempted to forbid the custom of pillage in 1652, but this rule was impossible to enforce, and the right to pillage was given statutory force after the Restoration.[15]

Some rewards that were previously customary or discretionary for privateers became entitlements 1643, when an ordinance passed by the Commonwealth parliament allowed them to retain any ships and goods captured after adjudication in an Admiralty Court and payment of one-tenth of the value of the prize and customs duties on any goods. A further ordinance of 1649 relating to naval ships, which applied during the First Anglo-Dutch War, entitled seamen and subordinate officers to half the value of a captured enemy warship and gun money of between 10 and 20 pounds for every gun on an enemy warship that was sunk, and one third of the value of a captured enemy merchant ship. If a captured enemy warship were repairable at reasonable cost and suitable to add to the English fleet, the Crown might but bought it.[16] However, until 1708, the purchase price was fixed by the Admiralty, whose agents were suspected of valuing them cheaply or inflating the cost of repairs.[17] The 1643 ordinance also introduced two new measures: that part of the money not allocated to the ship's crew would go to the sick and wounded, and that English ships recaptured from an enemy were to be returned to their owner on payment of one-eighth of their value to the ship recapturing them. A further ordinance of 1650 applied these prize money rules to the capture of pirate ships.[18]

The provisions of 1643, 1649 and 1650 on the distribution of prize money were repeated after the Restoration in an act of 1661, which also expressly allowed the custom of pillage, and allowed the Lord Admiral discretion over any money or goods not allocated to the crews. The right of disposing of captured prizes and pre-emption in acquiring their goods was also retained by the Lord Admiral.[19]

Anglo-Dutch Wars

Even before the Second Anglo-Dutch War formally began, two steps were taken by the English government that were liable to promote hostility between England and the Netherlands. Firstly, in 1663, the Navigation Act, which aimed to restrict Dutch maritime trade, authorised the capture of English or foreign vessels trading in breach of that act as prizes, and allowed Vice-Admiralty courts in the English colonies to adjudicate their value, and to award one-third of this value to the captor, one third to the colonial governor and one third to the Crown. These overseas Vice-Admiralty courts were, from 1692, also able to deal with wartime prizes.[19] Secondly, an Order in Council of 1644 increased the prize money due to the seamen of English ships that took prizes to 10 shillings for each ton comprised in their tonnage, and gun money of at least 10 pounds a gun for any warship sunk or burned.[20]

Although neither Charles II nor his brother James, Lord High Admiral since 1660, had been ungenerous to those Royal Navy captains and flag officers that captured enemy ships, giving them a fair allocation of the value of their prizes, the failure to set out a fixed scale of prize money for senior officers led to a scandal in 1665.[21] The Earl of Sandwich commanded an English fleet that, between 3 September and 9 September, had captured thirteen Dutch East India Company merchant ships of the East Indies spice fleet, and had also captured or sunk several of their escorts. Concerned that Charles's difficult financial position might make him less generous that before, and considering the great value of the cargoes captured, Sandwich, urged on by one of his flag officers, Sir William Penn, agreed that he and Penn should take goods to the value of 4,000 pounds, and that each other flag officer and the three captains that held knighthoods should take goods worth 2,000 pounds, from the captured cargoes: nothing was provided for the untitled captains.[22]

This seizure of goods was represented by Sandwich and Penn as a payment on account of their expected prize money, although it was in clear breach of the instructions issued in 1665 at the outbreak of the war that required ships and goods to be declared as lawful prizes by an Admiralty court before any goods in its hold could be removed.[23] Three of those officers offered 2,000 pounds of goods refused to take them, and the untitled captains complained against the arrangement. In the course of the removal of goods from the Dutch ships' holds, many English sailors joined in the plundering, and a large quantity of spices and other valuable goods were stolen or spoilt. The Earl of Sandwich lost his command, and the government lost goods and money that could have been used to send the fleet back to sea.[24]

English privateers were very prominent at sea during the Anglo-Dutch Wars, attacking the maritime trade and fisheries on which the United Provinces depended, capturing many Dutch merchant ships.[25]

War of the Spanish Succession

The situation of ships' captains was remedied by a Prize Act of 1692. This act distinguished between captures made by privateers and by royal ships. Privateers were entitled to retain any ships captured and four-fifths of the goods, surrendering one-fifth of those to the Crown, and it was left to them how they sold their prizes and distributed the proceeds. However, in the case of captures by royal ships, one-third of their value went to the officers and men of the captor, and one third to the king, from which he could reward flag officers. The final one-third was to benefit those sick and wounded, as before, and for the first time was also used to pay dependents of crew members killed and to fund Greenwich Hospital.[26]

The 1692 act also abolished the ancient right of pillage, standardised gun money at 10 pounds a gun and provided for salvage to be paid by the owners of English ships recaptured from the enemy.[27] Until 1692, the allocation of the one-third of the value of prize money due to the officers and men had been a matter of custom, but it was then fixed as one-third (or one-ninth of the total prize money) to the captain, one-third to other officers and one-third to the crew.[28]

During this war, in 1701, the Admiralty had established a board of prize commissioners, who appointed local prize agents at British and some colonial ports, and were responsible for the custody of ships captured both by privateers and royal ships until these captures were either condemned or released. Although privateers were free to dispose of prize ships and goods after they were condemned and any duties were paid, the prize commissioners were responsible for the sale of ships and cargoes captured by royal ships, the valuation of ships or goods acquired for Royal Navy use, and the calculation and payment of prize money. As many naval actions in this war took place in the Mediterranean or Caribbean, some captains disposed of captured ships without bringing them before an Admiralty prize agent, often defrauding their own crews of all or part of their prize money entitlement. A Royal Proclamation of 1702 made captains that failed to act through prize agents liable to court martial and dismissal.[29] If the Admiralty Court found that a seizure was unlawful, the ships and cargo was restored to its owner, and the captor would be responsible for any loss or costs arising.[30]

Great Britain, 1707 to 1801

After the Act of Union 1707 between England and Scotland, the former English prize money rules applied to Great Britain. The War of the Spanish Succession continued until 1714.

An act of 1708, generally known as the Cruisers and Convoys Act was designed to protect British maritime trade by allocating Royal Navy ships to protect convoys, by encouraging privateers to assist in protecting convoys and amending the prize rules to encourage naval ships to attack enemy warships, and both Royal Navy ships and privateers to attack enemy privateers and merchant ships. The two main changes to the made under this act were the abolition of the Crown's shares in the value of merchant ships and their cargoes captured by naval vessels, and of goods captured by privateers, and the payment of head money of five pounds for each crew member of a captured or sunk enemy warship, as far as these could be established, replacing gun money. As with other prize acts, this ceased to have effect at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, although its provisions were largely repeated in subsequent prize acts of 1756, 1776, 1780 and 1793, issued at the outbreaks of conflicts or to include new belligerents.[31][32] Occasionally, if an enemy merchant ship were captured where it was difficult to take it to an Admiralty Court or prize agent, the captor might offer to ransom it for 10% to 15% of its estimated value.[33] In 1815, ransoming was prohibited except in case of necessity, for example where an enemy warship were nearby.[34]

The 1708 act still required captured ships to be placed in the custody of Admiralty prize agents before adjudication by the Admiralty Court, and of paying customs duties on captured cargoes. However, once they had paid these duties, Royal Navy captors were free to sell these cargoes at the best prices rather than having to sell them through Admiralty prize agents, as privateers had always been able to do so. The act also allowed Royal Navy captains, officers and crews to appoint their own experts and prize agents to dispute the value of ships or goods acquired for naval use and collect prize money on their behalf.[35] Admiralty appointed prize agents were, however, now entitled to a fee of 2% in Britain and 5% abroad. The various changes brought in by this act are regarded as the basis for the fortunes made from prize money in the 18th and early 19th centuries.[36]

Distribution

In the Georgian navy, shares of prize money were based on rank. As there were few senior officers, their individual shares were larger than junior officers and very much larger than those of the seamen. The percentages of prize money granted to senior officers were generally higher in the 18th century than in most of the 19th century. Although shares varied over time, and captains within a fleet or squadron could agree alternative sharing arrangements, in the 18th century, an admiral could generally receive one-eighth of the value of all prizes taken by his fleet or squadron, and if there were more than one admiral, they would share that eighth. A captain usually received one-quarter of the value his prize, or three-eighths if not under the command of an admiral. The distribution for other officers and men was less detailed than it later became: other officers shared another quarter and the crew shared the remainder. Any ships within sight of a battle also participated in the sharing of prize money, and any unclaimed prize money was allocated to Greenwich Hospital.[37]

During the Seven Years' War, the crews of privateers operating from the British colonies in America and the Caribbean were often paid wages as well as a share of prize money, but the crews of those operating from British ports usually received no wages and the cost of the provisions they consumed was deducted from their prize money. The owners of privateers generally took half the value of any prize and also charged a further 10% to cover prize agents' fees and other commissions. The captain received 8% of the value by custom, leaving 32% to be shared by the other officers and crew. It was common practice to divide this into shares, with the officers receiving several times as much as seamen, their relative shares being agreed at the start of the voyage.[38]

Notable awards, 1707 to 1801

Perhaps the greatest amount of prize money awarded for the capture of a single ship was for that of the Spanish frigate Hermione on 31 May 1762 by the British frigate Active and sloop Favourite. The two captains, Herbert Sawyer and Philemon Pownoll, received about £65,000 apiece, while each seaman and Marine got £482 to £485.[39][40][41] The total pool of prize money for this capture was £519,705 after expenses.[42]

However, the capture of the Hermione did not lead to the largest award of prize money to an individual. As a result of the Siege of Havana, which led to the surrender of that city in August 1762, 10 Spanish ships-of-the-line, three frigates and a number of smaller vessels were captured, together with large quantities of military equipment, cash and merchandise. Prize money payments of £122,697 each were made to the naval commander, Vice-Admiral Sir George Pocock, and the military commander, George Keppel, 3rd Earl of Albemarle, with £24,539 paid to Commodore Keppel, the naval second-in-command who was Albemarle's younger brother. Each of the 42 naval captains present received £1,600 as prize money.[43] The military second-in-command, Lieutenant-General Eliott, received the same amount as Commodore Keppel, as the two shared a fifteenth part of the prize pool, as against the third shared by their commanders.[44] Privates in the army received just over £4 and ordinary seamen rather less than £4 each.[45]

The prize money from the capture of the Spanish frigates Thetis and Santa Brigada in October 1799, £652,000, was split up among the crews of four British frigates, with each captain being awarded £40,730 and the seamen each receiving £182 4s 93⁄4d or the equivalent of 10 years' pay.[46]

United Kingdom from 1801

After the Act of Union 1801 between Great Britain and Ireland, the former prize money rules of Great Britain applied to the United Kingdom. The Treaty of Amiens of March 1802 ended the hostilities of the French Revolutionary Wars and those of the Napoleonic Wars commenced in May 1803, when the United Kingdom declared war in France.

Prize acts at the start of war with France and Spain repeated the provisions of the 1793 Act, which in turn largely repeated those of 1708.[47] The basis of distribution under these acts is detailed in the next section. However, a proclamation of 1812 soon after the start of the War of 1812 made a further revision to the rules on allocation, such that the admiral and captain jointly received one-quarter of the prize money with one-third of this going to the admiral, a reduction from their previous entitlement. The master and lieutenants received one-eighth of the prize money, as did the warrant officers. The crew below warrant officer rank now shared one-half of the prize money. However, this group was subdivided into several grades, from senior petty officers down to boys, with the higher grades gaining at the expense of the lower ones.[48] The Prize Act of 1815, issued after Napoleon's return from Elba, largely repeated the allocation below the flag officers' share into eight grades and, although it lapsed in the same year, its provisions were re-enacted in 1854 at the start of the Crimean War.[49]

The multiplicity of prize money grades survived until 1918, with some refinements to include new ratings required for steamships. The Naval Agency and Distribution Act of 1864 was a permanent act, rather than one enacted at the start of a particular conflict, stating that prize money was to be distributed according to a Royal Proclamation or Order in Council issued when appropriate.[50] This act made no provision for privateers as the United Kingdom had signed the Declaration of Paris, which outlawed privateering by the ships of signatory nations.[51] The Royal Proclamation on the division of prize money dated 19 May 1866 provided for a single admiral to receive, or several admiral to share, one-thirtieth of the prize money pool; a single captain or commanding officer to receive, or several share, one-tenth of the pool, and the residue to be allocated to officers and ratings in 10 classes in specified shares.[52]

The Prize Courts Acts of 1894 provided that regulations for setting up of prize courts and on prize money should in future be initiated at the start of any war only by an Order in Council and not by Royal Proclamation. The Naval Prize Act 1918 changed the system to one where the prize money was no longer paid to the crews of individual ships, but into a common fund from which a payment was made to all naval personnel. The act also stated that no distribution would occur until after the end of the war. The award of prize money in the two world wars were governed by this legislation, which was further modified in 1945 to allow for the distribution to be made to Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel who had been involved in the capture of enemy ships. The Prize Act 1948 abolished the Crown prerogative of granting prize money or any money arising from Droits of the Crown in wartime.[53]

For more on the prize court during World War I, see Maxwell Hendry Maxwell-Anderson.

Anti-slavery

After the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807, an additional source of prize money arose when Royal Navy ships of the West Africa Squadron captured slave ships. Under an Order in Council of 1808, the government paid 60 pounds for each male slave freed, 30 pounds for each woman and 10 pounds for each child aged under 14. This was paid in lieu of any prize money for the captured slave ship, which became the property of the British government, and it was allocated in the same proportions as other prize money. Between 1807 and 1811, 1,991 slaves were freed through the Vice-Admiralty Court of Sierra Leone, and between 1807 and mid-1815, HM Treasury paid Royal Navy personnel 191,100 pounds in prize money for slaves freed in West Africa. Condemned slave ships were usually auctioned at Freetown and re-registered as British ships.[37][54] However, in 1825, the bounty for all slaves was reduced to a flat rate of 10 pounds, and it was further reduced to 5 pounds for each live slave in 1830. The decline in captures prompted an increase in prize money in 1839 to 5 pounds for each slave landed alive, half that sum for slaves that had died and one pound and ten shillings for each ton of the captured vessel's tonnage.[55]

Distribution

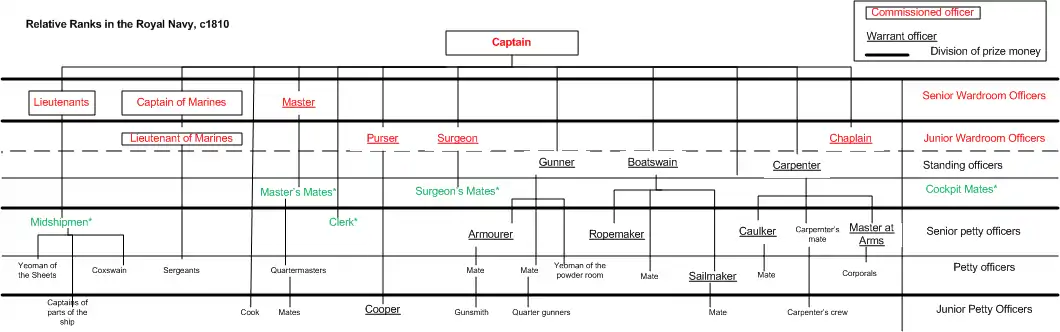

The following scheme for distribution of prize money was used for much of the Napoleonic wars until 1812, the heyday of prize warfare. Allocation was by eighths. Two eighths of the prize money went to the captain or commander, generally propelling him upwards in political and financial circles. One eighth of the money went to the admiral or commander-in-chief who signed the ship's written orders (unless the orders came directly from the Admiralty in London, in which case this eighth also went to the captain). One eighth was divided among the lieutenants, sailing master, and captain of marines, if any. One eighth was divided among the wardroom warrant officers (surgeon, purser, and chaplain), standing warrant officers (carpenter, boatswain, and gunner), lieutenant of marines, and the master's mates. One eighth was divided among the junior warrant and petty officers, their mates, sergeants of marines, captain's clerk, surgeon's mates, and midshipmen. The final two eighths were divided among the crew, with able and specialist seamen receiving larger shares than ordinary seamen, landsmen, and boys.[56][57] The pool for the seamen was divided into shares, with each able seaman getting two shares in the pool (referred to as a fifth-class share), an ordinary seaman received a share and a half (referred to as a sixth-class share), landsmen received a share each (a seventh-class share), and boys received a half share each (referred to as an eighth-class share).

A notable prize award related to a capture in January 1807, when the frigate Caroline took the Spanish ship San Rafael as a prize, netting Captain Peter Rainier £52,000.[40]

Operational difficulties

For much of the 18th century and until 1815, the main complaints about prize money concerned delays in its payment and practices that deprived ordinary seamen of much of what was due to them. Although the incidence of captains selling captured ships abroad and defrauding crews of prize money reduced greatly in the course of the century, payment was often by way of a promissory note, or ticket to be paid when the relevant naval department had funds. Although officers could generally afford to wait for payment, which was often made only in London and sometimes in instalments that might stretch over several years, most seamen sold their promissory notes at a large discount.[58] Other seamen authorised another individual to collect their prize money, who did not always pass it on, or lost out when they transferred to a new ship, if their prize money were not forwarded. A final issue of contention was that the value of prizes assessed in overseas Vice-Admiralty courts could be reassessed in the Admiralty Court in Britain if the Admiralty appealed the initial valuation. Excessive valuations in Vice-Admiralty courts, particularly in the West Indies, arose because the courts charged fees based on the prizes' values.[59] This led to delays and possible reduced payments.[60]

To some extent, delays arose from the time taken by Vice-Admiralty courts adjudicating whether captured ships were legitimate prizes and, if they were, their value. In the War of 1812, the Vice-Admiralty courts at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and, to a lesser extent, Bermuda had to deal with many, often small, American ships captured both by privateers and naval vessels, leading to lengthy legal delays in adjudication. Once an adjudication was made, providing there was no appeal, the funds from the sale of a captured ship or its goods should have been available for payment within two years, but the whole process from capture to payment might take three years or more.[61]

Under the so-called joint capture rules, which did not apply to privateers, any Royal Navy ship present when a capture took place was entitled to share in the prize money. However, this rule led to disputes where, for example, three claimant ships had been pursuing the captured ship but were out of sight when another captured it, or where a squadron commander claimed a share in a prize captured by his subordinate in disobedience to that commander's orders. In order to minimise disputes, some captains and crews of ships on the same mission made time-limited agreements to share prize money.[30] In the case of privateers, for one to claim a share of prize money, it had to give actual assistance to the ship making the capture unless there were a prior agreement between privateers to share prizes.[62]

Scotland and Ireland

Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland had its own Lord High Admiral from mediaeval times until 1707, except for the period 1652 to 1661. His jurisdiction over Scottish ships, waters and coasts, exercised through a High Court of Admiralty, was similar to that of his English equivalent.[63] In 1652, the Scottish fleet that was absorbed into the Commonwealth fleet and, although a separate Scottish Admiralty was re-established in 1661, it had no warships designed as such until three relatively small ones were commissioned in 1696.[64]

However, as Scotland was involved in the Second (1665–67) and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars (1672–74) against the Dutch and their allies, the Scottish Admiralty commissioned a significant number of privateers in both conflicts by issuing Letters of marque.[65] Although Scottish privateers were generally successful in 1666 and later, their activities in 1665 were limited, because of delays in the Scottish Admiral issuing regular Letters of marque at the start of the war.[66] At least 80 privateers operating from Scottish ports in these two wars have been identified, and contemporaries estimated as many as 120 may have operated against Dutch and Danish merchant ships, including some English ships operating under Scottish commissions.[67] Apart from ships of the Dutch East India Company, many Dutch merchant ships and of its Danish ally were poorly armed and undermanned. Most of these engaged in Atlantic trade had to sail around the north of Scotland to avoid the English Channel in wartime, and the Dutch whaling and herring fleets operated in waters north and east of Scotland, so they were vulnerable Scottish privateers, who were particularly successful in the Second Anglo-Dutch War.[68] The owners of privateering vessels, were entitled to the greater part of the value of their prizes, as their ordinary seamen usually served for wages rather than a share of prize money.[69]

Ireland

Admirals of Ireland were appointed in the late Middle Ages to what was a mainly honorific position involving few official tasks. However, from the late 16th century, these admirals became the Irish representatives of the Lord Admiral of England. They were sometimes referred to as the Vice-Admiral of Ireland, but had no control over the royal fleet in Irish waters. Ireland also had its own Admiralty Court from the late 16th century, mainly staffed by English admiralty officials and with a jurisdiction was broadly similar to that of its English counterpart.[70] Much of its activities concerned the many pirates operating off the coast of Ireland during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The Irish Admiralty had no ships of its own and no authority to issue Letters marque to privateers, but could seize and condemn pirate and enemy ships in Irish ports.[71]

The Irish Admiralty was granted permission to establish a prize court at the time of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, which was considered to be the equivalent of the Vice-Admiralty courts in British colonies.[72] At the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1744, the Irish Admiralty Court managed to extend its powers and jurisdiction by obtaining independent prize jurisdiction and enhancing its status from that of a Vice-Admiralty to that of an independent court.[73]

France

In France, prize jurisdiction lay with the Admiral of France until that office was suppressed in 1627. A commission of jurists, the prize council (Conseil des Prises), was established in 1659 to deal with the adjudication of all prizes and the distribution of prize money, although many French privateers tried to evade its scrutiny.[74] Cormack (2002), p. 76. The Prize Council only functioned in times of war until 1861: it then became permanent until its dissolution in 1965.[75]

Although officers and men of the French Navy were, in principle, entitled to prize money, and depriving men of prize money due to them was an established disciplinary measure, awards were relatively rare.[76] During the 17th and 18th centuries, French naval strategy alternated between that of guerre d'escadre, maintaining a fully-equipped battle fleet for control of the sea, and guerre de course, sometimes using naval ships but more often privateers, including smaller naval warships leased to private individuals, to destroy an enemy's maritime commerce. Although these alternatives had a strategic basis, only guerre de course was viable when financial problems prevented the maintenance of a battle fleet.[77] Even when it was possible to equip a battle fleet, the French naval doctrine that a fleet must avoid any action that might prevent it carrying out its designated mission, prioritised defensive tactics which made captures and prize money unlikely.[78]

When a policy of commerce raiding was adopted, the major warships were laid up, but many of the smaller warships manned by the officers and men of the French Navy, were leased by the French Crown to contractors, who paid the fitting-out and running costs of these ships, and agreed to pay the Crown one-fifth of the value of all captures.[79] Jenkins (1973), These ships were, however, regarded as privateers, and other privateers were entirely financed by private individuals: in both cases, the privateers operated as their owners and lessees wished, outside if government control. Privateering denied the French Navy of recruits who were experienced seamen, already in short supply in France.[80]

Under an ordinance of 1681, privateers, both those using their own ships and those leasing royal ships were required to register with an officer of the Admiralty and make a substantial cautionary deposit. Any prize obtained by a privateer was to be surveyed by representatives of the prize council, who would recover their costs out of the sale proceeds, and retain a tenth of the net proceeds as the Admiralty portion.[81] Officers and men of the French Royal Navy were entitled to share four-fifths of the value of a merchant ship captured, with one tenth of the proceeds retained by the Admiralty and a further tenth for sick and injured seamen. Gun money for an enemy warship or armed privateer captured or destroyed.[82] The Admiralty tenth was sometimes waived when the government wished to encourage commerce raiding, and the distribution of prize money to the officers and crews, and to owners of private ships, was governed by custom, not by any ordinance. The prize council was notorious for the lengthy delays in dealing with cases, during which the prizes and their cargoes deteriorated.[83]

Prize money was awarded to French naval personnel up to 1916, after which amounts that would have been paid as prize money were allocated to a fund for naval widows and wounded.[84]

Dutch Republic

During the Dutch Revolt, William the Silent as sovereign Prince of Orange, was able to issue letters of marque to privateers and, before the end of the 16th century five partly autonomous admiralties had emerged, under the oversight of the states general. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the each of these was responsible for providing warships to the navy of the Dutch Republic and acting as prize courts for captures by both for their own warships and for privateers to whom they had given commissions, although these were formally issued in the name of the states general.[85] From the 1620s, the states general also delegated authority to the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company to issue Letters of marque valid within each company's area of operation.[86] In the 17th century, the greatest number of privateers operated under the jurisdiction of the Admiralty of Zeeland, and its councillors based in Middelburg spent a great deal of time dealing with the complex business of adjudicating prizes. Prizes were normally sold by auction, and the large numbers captured in the 17th century wars against Spain, England and France depressed prices and restricted the prize money crews received.[87]

Although prize money was an important supplement to the income of the officers of Dutch warships, there has been little research on how the five admiralties calculated the amounts of prize money distributed to the officers and men capturing prizes. The lieutenant-admiral of an admiralty generally received four times as much as the captain responsible for a capture, and the vice-admiral twice as much: in both cases, these flag-officers shared in all ships and goods taken by captains in their admiralties, even when not present at the capture.[88] In 1640, Maarten Tromp, a lieutenant-admiral was owed 13,800 guilders, mostly his share of prize money from the Battle of the Downs the previous year.

Both captains and flag officers in the Dutch fleet sometimes put the pursuit of prize money before discipline. In the Four Days' Battle of June 1666, several Dutch ships left the fleet either towing English ships they had captured or in pursuit of prizes,[89] and Cornelis Tromp was extremely reluctant to burn HMS Prince Royal after it had run aground and been damaged, despite the orders of his commander, Michiel de Ruyter. Tromp attempted to claim compensation for its loss for many years.[90] For ordinary seamen, prize money was rare, the amounts small and payment was often delayed.[91] In many cases, prize money was paid in installments over several years and crew members frequently sold advance notes for the later instalments at far below their face value, especially in the 18th century, when several of the Admiralties were in financial difficulties.[92]

Privateering was already established when the Dutch Republic broke away from Spain: it quickly developed in the late 16th century and expended further in the 17th century.[93] In many cases, Dutch privateers attempted to evade the prize rules, by attacking neutral or even Dutch ships, failing to bring captures or their cargoes for adjudication and removing and selling cargoes to avoid paying duties.[94] Privateers licensed by the two Dutch India companies were aggressive in attacking what they termed interlopers in their areas of operations, regardless of nationality, and both companies were active in privateering in the three Anglo-Dutch wars. .[95]

During the Eighty Years' War, the main targets of Dutch privateers were Spanish and Portuguese ships, including those of the Spanish Netherlands. Privateers licensed by the West India Company were very active against ships trading with Brazil.[96] The privateers that had attacked Portuguese shipping had to cease doing so after the 1661 Treaty of The Hague, but many quickly transferred their activities to attacking English shipping after 1665 during the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch wars.[97] However, there was relatively little Dutch privateering after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, a consequence of the general decline in Dutch maritime activity.[98]

United States

To 1814

During the Revolutionary War period, the Continental Congress had no navy and relied heavily on privateers who had been authorised by one of the states to capture British ships. Admiralty courts for the state that had authorised the privateer adjudicated on the ownership of captured vessels and their value, and were subject to oversight by a committee of Congress.[99] The Continental Navy, formed in 1775, was small and outmatched by the Royal Navy, whereas American privateers captured about 600 British merchant ships in the course of this conflict.[100] In 1787, the US Constitution transferred the right to grant letters of marque from the states to Congress.[101]

At the start of the War of 1812, the few larger US Navy ships were laid-up, while the Royal Navy had relatively few resources available in the western Atlantic, leaning the field free for privateers on both sides.[102] However, once the US Navy frigates were brought back into commission, they achieved some spectacular successes against weaker British frigates, with Stephen Decatur and John Rodgers both receiving over 10,000 dollars in prize money.[103] However, later in the war, the Royal Navy succeeded in blockading the US Eastern seaboard and capturing several US Navy vessels and a number of merchant ships, and also stifling American privateer activity, although single US Navy warships managed to avoid the blockade and attack British shipping in the Caribbean and off South America.[104]

From the inception of its navy, the United States government granted naval personnel additional payments of two kinds, prize money, being a share in the proceeds from captured enemy merchant vessels and their cargo, and head money, a cash reward from the US Treasury for sinking enemy warships. From 1791, US Navy personnel received half the proceeds of a prize of equal or inferior force, and all the proceeds of a vessel of superior force. Privateers, in contrast, received all the proceeds of any prize, but had to pay duties that rose to 40% during the War of 1812, although they were lower at other times. Generally, half of the net amount went to the owners of the privateer, half to the crew.[105] From 1800, US Navy ships that sunk an armed enemy ship received a bounty of twenty dollars for each enemy crew member at the start of the action, divided among the crew of that ship in the same proportions as other prize money.[106]

Distribution

Under United States legislation of 1800, whether the officers and men of the navy ship or ships responsible for the capturing a prize were entitled to half of the assessed value of the prize, or the whole value in the case of a capture of superior force, the prize money fund was to be allocated in specified proportions. The captain or captains of vessels taking prizes were entitled to 10% of the prize money fund, and the commander of the squadron to 5% of the fund. In the event that the captain was operating independently, he received 15% of the prize fund. Naval lieutenants, captains of marines and sailing masters were to share 10%, increased to approximately 12% if there were no lieutenants of marines. Chaplains, lieutenants of marines, surgeons, pursers, boatswains, gunners, carpenters, and master's mates shared 10% of the prize fund, reduced to approximately 8% if there were no lieutenants of marines. Midshipman, junior warrant offices and the mates of senior warrant officers shared 17.5% and a range of petty officers a further 12.5%. This left 35% for the rest of the crew. Any unclaimed prize money was to be retained jointly by the Navy and Treasury secretaries to fund disability pensions and half-pay.[107]

From 1815

For most of the period between the end of the War of 1812 and the start of the American Civil War, there was little opportunity to gain prize money. After the outbreak of the Civil War, the Confederate States granted some 30 commissions or letters of marque to privateers, which captured between 50 and 60 United States merchant ships. However, a declaration by Abraham Lincoln that Confederate privateers would be treated as pirates and the closure of the ports of European colonies in the Caribbean as venues for the disposal of prize vessels and cargoes encouraged their owners to turn to blockade running.[108]

From 1861, US Navy ships engaged Confederate privateers and blockade runners: as the 1800 legislation only applied to enemies of the United States, which did not recognise the Confederate States, it was unclear if prize money would apply. However, a revised statute of 1864 stated that "the provisions of this title shall apply to all captures made as prize by authority of the United States", allowing prize money claims to be made.[109] Over 11 million dollars of prize money was paid to US Navy personnel for captures in the Civil War period. It has been calculated that about one-third of prize money due was payable to officers under the prevailing rules, but that approximately half of the money actually paid went to officers, most probably because of the difficulty in tracing enlisted men when payments were delayed.[110]

In 1856, the Declaration of Paris was signed: this outlawed privateering by the ships of the 55 nations that signed it. However, the United States did not sign the declaration, in part because it considered that, if privateering were to be abolished, the capture of merchant ships by naval vessels should also cease. Despite this, the United States agreed to respect the declaration during the American Civil War, although Lincoln's cabinet did discuss the use of privateers against British merchant shipping in the event Britain recognised the Confederacy.[111]

A number of changes were made to the allocation of prize money to US Navy personnel in the 19th century in the last being in 1864. This preserved the awards 5% of the prize fund to commanders of the squadron, which now also applied to fleet commanders of fleet and of 10% to captains under the immediate command of a flag officer or 15% for those operating independently. It added new awards of 2% for a commander of a division of a fleet under the orders of a fleet commander and 1% for a fleet captain stationed on the flagship. The most significant change was that the residue of prize money after making these awards was to be divided amongst the remaining officers and men in proportion to their rates of pay. This law also increased the bounty or head money for destroying an enemy warship in action, or any other enemy ship that it was necessary to destroy was increased to 100 dollars for each enemy crew member at the start of the action on a ship of less or equal force, or 200 dollars for each crew member of an enemy ship of greater force, to be divided among the officers and men of the US ship in the same proportions as other prize money.[112]

The small size of US Navy meant that privateering would be the main way it could attack enemy commerce. Until the early 1880s, American naval opinion considered that privateering remained a viable option, although subsequent increases in the size of the US Navy changed this view.[113]

In the Spanish–American War of 1898, neither the United States nor Spain issued commissions to privateers. However, the US Navy was granted what were to be last payments of prize money made by the US Treasury for that war. These were to sailors that took part in the battles of Manila Bay and Santiago and divided prize funds of 244,400 dollars and 166,700 dollars respectively, based on the estimated numbers of Spanish sailors and the value of ships salvaged at Manilla.[114]

Abolition

During the Spanish American War in 1898, the US Navy was seen by much of the United States population as seeking to profit from prize money and head money to an unacceptable extent, even though the amounts granted were relatively modest. All awards of prize money and head money to US Navy personnel were abolished by an overwhelming vote of Congress in March 1899, shortly after the Spanish-American War concluded.[115]

It is sometimes claimed that the US Navy last paid prize money in 1947.[116] USS Omaha and USS Somers (DD-381) intercepted the German cargo ship Odenwald on 6 November 1941 while on Neutrality Patrol in the area of the western Atlantic in which the United States had prohibited warships of belligerent powers from operating. Although the Odenwald was not a warship, it was sailing under the United States flag and claiming to be registered there, and also carrying contraband, either of which rendered the ship liable to arrest although not condemnation as a prize. After the Odenwald was stopped, its crew tried to scuttle it and took to the lifeboats. However, a boarding party from the Omaha managed to prevent the Odenwald from sinking and sailed it first to Trinidad, then to Puerto Rico. The United States was not at war with Germany at the time, and after the war, the Odenwald's owners claimed that its seizure was therefore illegal. The Admiralty Court in Puerto Rico, however, ruled in 1947 that the crew's attempt to scuttle the ship, and then abandon it, meant that the Omaha's boarding party and salvage party that jointly brought the Odenwald to port had salvage rights, worth approximately 3 million dollars. It also ruled explicitly that it was not a case of bounty or prize.[117]

End of prize money

Privateers

Privateers were most numerous in European waters during the seventeenth and early eighteenth-century wars, in conflicts involving Britain, France and the Dutch Republic, and outside Europe in the percent in the American War of Independence, the War of 1812 and colonial conflicts in the Caribbean, involving Britain, France and the United States. However, between 1775 and 1815, revenues declined sharply, largely because the probability of seizing a prize ship fell dramatically, partly owing to the increasing numbers of naval vessels competing for captures. As outfitting and manning ships for commerce raiding was expensive, privateering became less financially attractive.[118]

The Declaration of Paris 1856, by outlawing privateering by ships of signatory nations, would have made it politically difficult for non-signatories, which included the United States to commission privateers in a future conflict,[111] and the privateering using metal-hulled steamships presented the additional problems of maintaining complex engines, the need for frequent re-coaling and to repair more complex damage than that experienced by wooden-hulled sailing ships. In addition, after 1880, many maritime countries paid subsidies so that liners and other fast merchant vessels were built with a view to conversion into armed merchant cruisers under naval control in wartime, which replaced the need for privateers, and no privateers were commissioned after the American Civil War.[119][120]

References

- Wright 16

- Wright 23

- Wright 21-23

- Wright 22, 24

- Wright 27

- Wilson, Hammar & Seerup 5, 163-164

- Phillimore, 214-215

- Van Niekerk, 123

- Phillimore, 227-229

- Holdsworth 559-560

- Wright 31-33

- Marsden (1915) 91-92

- Wright 45-46

- Marsden (1909) 695, 697

- Wright 51

- Marsden (1911) 37

- Bromley 451

- Wright 50-51

- Marsden (1911) 43-44

- Fox 74

- Fox 113

- Fox 113-114

- Marsden, (1911), pp. 44–45.

- Fox 115

- Fox 69-70

- Wright 53

- Marsden (1915) 90

- Ehrman 129-130

- Bromley 449-450

- Malcomson, 64-65

- Baugh 113-114

- Wright 58

- Hill, 99

- Malcomson, 68-69

- Rodger (1986) 128–130

- Bromley 451-452

- Allen, 213

- Rodger (1986) 97, 312

- "Capture of The Hermione". Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Nelson and His Navy – Prize Money". The Historical Maritime Society. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- W. H. G. Kingston. How Britannia Came to Rule the Waves. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Rodger (1986) 257

- Rodger (1986) 257-258

- Pockock p. 216

- Corbett (1986) 283

- Rodger (2005) 524

- Wright 59

- Hill, 204-205

- Wright 60-61

- Lushington, 106-107

- Parillo (2007), 62-63

- Lushington, 109-111

- O'Hare 116-117

- Helfman, 1143-1144

- Lloyd 79-81

-

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-87021-258-3. OCLC 20997619. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

Nelson's Navy Lavery.

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-87021-258-3. OCLC 20997619. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- Rodger (205) 522–524

- Bromley 474-476

- Rodger (1986) 317-318

- Malcomson, 65-66

- Malcomson, 63-64

- Van Niekerk 119

- Murdoch 10 237

- Murdoch 230 236

- Murdoch 27, 238-240

- Graham 68

- Murdoch 240-241

- Graham 69-70

- Murdoch 177

- Appleby & O'Dowd 229-300

- Appleby & O'Dowd 307, 315-316

- Costello 40

- Costello 23, 26

- Cormack 76

- Archives du Conseil des Prises 1854 to 1965//https://francearchives.fr/fr/findingaid/f0164f7014d16d2cb68bc56607a6700eebf6c874

- Cormack 27

- Symcox 3-5

- Jenkins 108, 342

- Jenkins 100-102

- Cormack 25

- Vallan 4-6

- Vallan 14-16

- Symcox 173

- Parillo (2013) 526

- Bruijn (2011) p. 5

- Lunsford 118-182

- Bruijn(2011) 8

- Bruijn(2011) 44, 104

- Fox 212, 218

- Fox 240

- Bruijn(2011) 46

- Bruijn(2011) 119-120

- Lunsford 118, 182

- Lunsford, 155-156

- Lunsford 183-184

- Klooster 43-44

- Bruijn (2011) 145

- Bruijn (2008) 56

- Mask & Mac Mahon 477, 480

- Mask & Mac Mahon 487

- Parrillo (2007) 3

- Kert 7-8

- Kert 114

- Kert 116-116

- Parillo (2007), 24

- Parillo (2007), 25

- Peters 47-48, Articles V, VI, IX and X

- Peifer 98-99

- Library of Congress, 315, Section 33

- Parillo (2013), 66

- Parillo (2007) 63

- Library of Congress, 309-301, Sections 10 & 11

- Parillo (2007) 4 10-11

- Knauth 70, 73

- Parillo (2013) 47, 308-309

- Nofi, Al (20 July 2008). "The Last "Prize" Awards in the U.S. Navy?" (205).

- Justia US Law. The Omaha, The Somers, The Willmotto, Philadelphia US District Court for the District of Puerto Rico (D.P.R. 1947) https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/71/314/1674790/

- Hillmann & Gathmann 732, 740, 746-748

- Coogan 22

- Parillo (2007) 76-78

Sources

- Appleby, J.C.; O'Dowd, M. (1985). "The Irish Admiralty: Its Organisation and Development, c. 1570-1640". Irish Historical Studies. 24 (96): 299–326. doi:10.1017/S0021121400034234. S2CID 164205451.

- Allen, D. W. (2002). "The British Navy Rules: Monitoring and Incompatible Incentives in the Age of Fighting Sail". Explorations in Economic History. 39 (2): 204–231. doi:10.1006/exeh.2002.0783. S2CID 1578277.

- Baugh, D. A. (2015). British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole. Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-40087-463-7.

- Bromley, J. S. (2003). Corsairs and Navies, 1600-1760. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-90762-877-4.

- Bruijn, Jaap (2008). Commanders of Dutch East India Ships in the Eighteenth Century. Woodbridge: The Boydel Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-622-3.

- Bruijn, Jaap (2011). The Dutch Navy of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-98649-735-3.

- Corbett, J. S. (1907). 'England in the Seven Years' War: A Study in Combined Strategy, Vol II. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Coogan, J. W. (1981). End of Neutrality: The United States, Britain, and Maritime Rights, 1899-1915. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80141-407-7.

- Cormack, W. S. (2002). Revolution and Political Conflict in the French Navy 1789-1794. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52189-375-6.

- Costello, K. (2008). "The Court of Admiralty of Ireland, 1745-1756". The American Journal of Legal History. 50 (1): 23–48. doi:10.1093/ajlh/50.1.23.

- Ehrman, John (1953). The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10764-511-0.

- Fox, Frank F. (2018). The Four Days' Battle of 1666. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-52673-727-4.

- Helfman, T. (2006). "The Court of Vice Admiralty at Sierra Leone and the Abolition of the West African Slave Trade". The Yale Law Journal. 39 (5): 1122–1156. doi:10.2307/20455647. JSTOR 20455647.

- Hill, J. R. (1999). Prizes of War: Prize Law and the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic Wars 1793-1815. London: Sutton. ISBN 978-0-75091-816-9.

- Hillmann, Henning; Gathmann, Christina (2011). "Overseas Trade and the Decline of Privateering". The Journal of Economic History. 71 (3): 730–761. doi:10.1017/S0022050711001902. JSTOR 23018337. S2CID 153730676.

- Holdsworth, William (1956). A History of English Law Volume IV (7th ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-42105-040-2.

- Jenkins, E. H. (1973). A History of the French Navy. London: McDonald and Jayne's. ISBN 978-0-35604-196-4.

- Kert, F. M. (2017). Prize and Prejudice: Privateering and Naval Prize in Atlantic Canada in the War of 1812. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-78694-923-3.

- Klooster, W. (2016). The Dutch Moment: War, Trade, and Settlement in the Seventeenth-Century Atlantic World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-50170-667-7.

- Knauth, A. W. (1946). "Prize Law Reconsidered". Columbia Law Review. 46 (1): 69–93. doi:10.2307/1118265. JSTOR 1118265.

- Library of Congress, U.S. Statutes at Large, 38th Congress, 1st session, Chapter CLXXIV: An Act to regulate Prize Proceedings and the Distribution of Prize Money, and for other Purposes (PDF).

- Lloyd, Christopher (2012). The Navy and the Slave Trade: The Suppression of the African Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-71461-894-4.

- Lunsford, V. W. (1999). Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-34952-980-3.

- Lushington, G. (2005). A Manual of Naval Prize Law (facsimile of the 1866 ed.). London: Creative Media Partners. ISBN 978-1-37925-646-5.

- Malcomson, Thomas (2012). Order and Disorder in the British Navy. Martlesham: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-119-1.

- Marsden, R. G. (1909). "Early Prize Jurisdiction and Prize Law in England, Part I". The English Historical Review. 24 (96): 675–697. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXIV.XCVI.675. JSTOR 550441.

- Marsden, R. G. (1911). "Early Prize Jurisdiction and Prize Law in England, Part III". The English Historical Review. 26 (101): 34–56. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXVI.CI.34. JSTOR 550097.

- Marsden, R. G. (1915). "Prize Law". Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation. 15 (2): 90–94. JSTOR 752481.

- Mask, D.; MacMahon, P. (2015). "The Revolutionary War prize cases and the origins of Diversity Jurisdiction". Buffalo Law Review. 63 (3): 477–547.

- Murdoch, Steve (2010). The Terror of the Seas? Scottish Maritime Warfare, 1513-1713. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-9-00418-568-5.

- O'Hare, C. W. (1979). "Admiralty Jurisdiction (Part 1)". Monash University Law Review. 6: 91–121.

- Parillo, N. (2007). "The De-Privatization of American Warfare: How the U.S. Government Used, Regulated, and Ultimately Abandoned Privateering in the Nineteenth Century". Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities. 19 (1): 1–95.

- Parillo, N. (2013). Against the Profit Motive: The Salary Revolution in American Government, 1780-1940. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30019-4753.

- Peifer, Douglas (2013). "Maritime Commerce Warfare: The Coercive Response of the Weak?". Naval War College Review. 66 (2): 83–109. JSTOR 26397373.

- Peters, Richard (1845). Public Statutes at Large of United States of America Volume II. Sixth Congress, Chapter XXIII: An Act for the better government of the Navy of the United States. Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown.

- Phillimore, G. G. (1901). "Booty of War". Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation. 3 (2): 214–230. JSTOR 752066.

- Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Glasgow: Fontana Press. ISBN 0-006-86152-0.

- Rodger, N. A. M. (2005). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-06050-0.

- Symcox, G. (1974). The Crisis of French Sea Power, 1688–1697: From the Guerre d'Escadre to the Guerre de Course. The Hague: Marinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-9-40102-072-5.

- Valan, R-J. (1763). Traité des prises: ou Principes de la jurisprudence françoise concernant les prises. La Rochelle: J. Legier.

- Van Niekerk, J. P. (2006). "Of Naval Courts Martial and Prize Claims: Some Legal Consequences of Commodore Johnstone's secret mission to the Cape of Good Hope and the "Battle" of Saldanha Bay, 1781 (Part 2)". Fundamina. 22 (1): 118–157.

- Wilson, Evan; Hammar, AnnaSara; Seerup, Jakob (1999). Eighteenth-Century Naval Officers: A Transnational Perspective. Cham: Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-03025-700-2.

- Wright, P. Q. (1913). Prize Money 1649–1815. Chicago: Project Gutenberg.