Heloderma

Heloderma is a genus of toxicoferan lizards that contains five species, all of which are venomous.[1] It is the only extant genus of the family Helodermatidae.

| Heloderma Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Infraorder: | Neoanguimorpha |

| Clade: | Monstersauria |

| Family: | Helodermatidae |

| Genus: | Heloderma Wiegmann, 1829 |

| Type species | |

| Heloderma horridum Wiegmann, 1829 | |

| Species | |

Description

The genus Heloderma contains the Gila monster (H. suspectum) and four species of beaded lizards. Their eyes are immobile and fixed in their head.[2][3] The Gila monster is a large, stocky, most of the time slow-moving reptile that prefers arid deserts. Beaded lizards are seen to be more agile and seem to prefer more humid surroundings.[4][5] The tails of all species of Heloderma are used as fat storage organs. The scales of the head, back and tail are bead-like, containing osteoderms for better protection. The scales of the belly are free from osteoderms. Most species are dark in color, with yellowish or pinkish markings.[6][7]

Venom

The venom glands of Heloderma are located at the end of the lower jaws, unlike snakes' venom glands, which are located behind the eyes. Also, unlike snakes, the Gila monster and beaded lizards lack the musculature to inject venom immediately. They have to chew the venom into the flesh of a victim. Heloderma venom is used only in defense. Venom glands are believed to have evolved early in the lineage leading to the modern helodermatids, as their presence is indicated even in the 65-million-year-old fossil genus Paraderma.[7][8] In general, one adult helodermatid has approximately 15 to 20 mg of venom, while the estimated lethal dose for humans is 5 to 8 mg.[9]

Diet

Helodermatids are carnivorous, preying on rodents and other small mammals, and eating the eggs of birds and reptiles.

Reproduction

All species of Heloderma are oviparous. The Gila monster typically lays 6 eggs, the beaded lizards up to about 18 eggs .[7] Comparing the different species, all eggs have a similar size, and the same holds true for their hatchlings.

Taxonomy

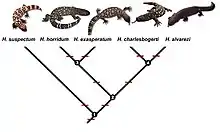

| Explanation of the numbers | |

|---|---|

| 1 | late Eocene (approx. 35 million years) |

| 2 | late Miocene (approx. 10 million years) |

| 3 | Pliocene (approx. 4.4 million years) |

| 4 | Pliocene (approx. 3 million years) |

Family Helodermatidae

- Genus Heloderma

- H. suspectum Cope, 1869; Gila monster

- H. horridum (Wiegmann, 1829); Mexican beaded lizard

- H. exasperatum Bogert & Martin Del Campo, 1956; Rio Fuerte beaded lizard

- H. charlesbogerti Campbell & Vannini, 1988; Guatemalan beaded lizard

- H. alvarezi Bogert & Martin del Campo, 1956; Chiapan beaded lizard

Members of the genus Heloderma have many extinct relatives in the Helodermatidae whose evolutionary history may be traced back to the Cretaceous period, such as Estesia. The genus Heloderma has existed since the Miocene, when H. texana lived, and fragments of osteoderms from the Gila monster have been found in late Pleistocene (8,000-10,000 years ago) deposits near Las Vegas, Nevada. Because the helodermatids have remained relatively unchanged morphologically, they are occasionally regarded as living fossils.[10] Although the beaded lizards and the Gila monster appear closely related to the monitor lizards (varanids) of Africa, Asia, and Australia, the wide geographical separation and unique features not found in the varanids indicates they are better placed in a separate family.[11]

The type species is Heloderma horridum, which was first described in 1829 by Arend Wiegmann. Although he originally assigned it the generic name Trachyderma, he changed it to Heloderma six months later, which means "studded skin", from the Ancient Greek words hêlos (ηλος)—the head of a nail or stud—and derma (δερμα), meaning skin.[12]

Conrad, 2008 and Estes et al., 1988 (using morphological data) places Helodermatidae within Varanoidea along with Lanthanotus borneensis and Varanus.[13][14] However, Estes et al., 1988 understood Helodermatidae as having split earlier from Lanthanotus and Varanus, whereas Conrad, 2008 groups them at the same branch point.

In contrast, molecular studies have identified Heloderma as being within Anguioidea along with Anguidae and Xenosauridae, but specifically sister to Anguidae.[15][16]

Venom

Venom production among lizards was long thought to be unique to this genus, but researchers studying venom production have proposed many others also produce some venom, all placed in the clade Toxicofera, which includes all snakes and 13 other families of lizards.[17] However, except for snakes, helodermatids, and possibly varanids, envenomation is not considered medically significant for humans

In captivity

H. horridum, H. exasperatum, and H. suspectum are frequently found in captivity and are well represented in zoos throughout much of the world. The other two species of Heloderma, H. alvarezi and H. charlesbogerti, are extremely rare, and only a few captive specimens are known.

Gallery

- Heloderma suspectum in captivity

Heloderma suspectum with 4 eggs

Heloderma suspectum with 4 eggs Heloderma suspectum with 6 eggs

Heloderma suspectum with 6 eggs Gila monster hatching

Gila monster hatching Group of young Gila monsters

Group of young Gila monsters

References

- http://herpetology.com/helobite.txt

- Wild and Exotic Animal Ophthalmology, Volume 1: Invertebrates, Fishes, Amphibians, Reptiles, and Birds

- The Biology of the Eye

- C. M. Bogert, R. M. Del Campo (1956). "The Gila Monster and its Allies. The relationships, habits, and behavior of the lizards of the family Helodermatidae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 109: 1–238.

- Beck, D. D. (2005). Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards. University Press of California.

- Schwandt, Hans-Joachim (2019). The Gila Monster Heloderma suspectum. Frankfurt/Main: Edition Chimaira. ISBN 978-3-89973-441-6.

- Bauer, Aaron M. (1998). Cogger, H.G.; Zweifel, R.G. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-12-178560-2.

- Richard L. Cifelli, Randall L. Nydam. 1995. Primitive, helodermatid-like platynotans from the Early cretaceous of Utah. Herpetologica. 51(3):286-291.

- Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- King, Ruth Allen; Pianka, Eric R.; King, Dennis (2004). Varanoid Lizards of the World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34366-6.

- Mattison, Chris (1998). Lizards of the World. London: Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-2357-2.

- Wiegmann, A.F.A. (1829). "Über die Gesetzlichkeit in der geographischen Verbreitung der Saurier". Isis. Oken. 22 (3–4): 418–428.

- Conrad, Jack L.; Ast, Jennifer C.; Montanari, Shaena; Norell, Mark A. (2011). "A combined evidence phylogenetic analysis of Anguimorpha (Reptilia: Squamata)". Cladistics. 27 (3): 230–277. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00330.x. ISSN 1096-0031. PMID 34875778. S2CID 84301257.

- Estes, Richard (1988). "Phylogenetic relationships within squamata". Phylogenetic Relationships of the Lizard Families: Essays Commemorating Charles L. Camp: 119–281. hdl:10088/6457. ISBN 9780804714358.

- Vidal, Nicolas; Marin, Julie; Sassi, Julia; Battistuzzi, Fabia U.; Donnellan, Steve; Fitch, Alison J.; Fry, Bryan G.; Vonk, Freek J.; Rodriguez de la Vega, Ricardo C.; Couloux, Arnaud; Hedges, S. Blair (2012-10-23). "Molecular evidence for an Asian origin of monitor lizards followed by Tertiary dispersals to Africa and Australasia". Biology Letters. 8 (5): 853–855. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0460. PMC 3441001. PMID 22809723.

- Townsend, Ted M.; Larson, Allan; Louis, Edward; Macey, J. Robert (2004-10-01). "Molecular Phylogenetics of Squamata: The Position of Snakes, Amphisbaenians, and Dibamids, and the Root of the Squamate Tree". Systematic Biology. 53 (5): 735–757. doi:10.1080/10635150490522340. ISSN 1063-5157. PMID 15545252.

- . Fry, B.; et al. (February 2006). "Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes". Nature. 439 (7076): 584–588. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..584F. doi:10.1038/nature04328. PMID 16292255. S2CID 4386245.

Notes

- Ariano-Sánchez, Daniel (2008). "Envenomation by a wild Guatemalan beaded lizard Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti". Clinical Toxicology. 46 (9): 897–899. doi:10.1080/15563650701733031. PMID 18608297. S2CID 22173811.

- Ariano-Sánchez, D. & G. Salazar. 2007. Notes on the distribution of the endangered lizard, Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti, in the dry forests of eastern Guatemala: an application of multi-criteria evaluation to conservation. Iguana 14: 152–158.

- Ariano-Sánchez, D. 2006. The Guatemalan beaded lizard: endangered inhabitant of a unique ecosystem. Iguana 13: 178–183.

- CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Archived 2018-09-30 at the Wayback Machine. 2007. Resume of the 14th Convention of the Parts. The Hague. The Netherlands.

External links

Schwandt, Hans- Joachim www.heloderma.net 2006 in 6 languages

Further reading

- C. M. Bogert, R. M. Del Campo (1956). The Gila Monster and its Allies. The relationships, habits, and behavior of the lizards of the family Helodermatidae. Vol. 109. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. pp. 1–238.

- Beck, D. D. (2005). Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards. London: University Press of California.

- Schwandt, Hans-Joachim (2019). The Gila Monster Heloderma suspectum. Frankfurt/Main: Edition Chimaira. ISBN 978-3-89973-441-6.

| Wikispecies has information related to Heloderma suspectum |

- About Beaded Lizards Archived 2015-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Heloderma information

- Family Helodermatidae (Gila Monsters) Archived 2010-07-15 at the Wayback Machine