Henry Gardner

Henry Joseph Gardner (June 14, 1819 – July 21, 1892) was the 23rd Governor of Massachusetts, serving from 1855 to 1858. Gardner, a Know Nothing, was elected governor as part of the sweeping victory of Know Nothing candidates in the Massachusetts elections of 1854.

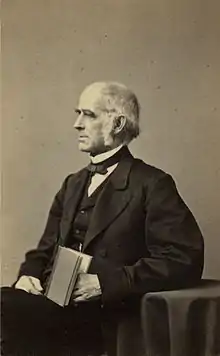

Henry Gardner | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jean Paul Selinger, 1890 | |

| 23rd Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 4, 1855 – January 7, 1858 | |

| Lieutenant | |

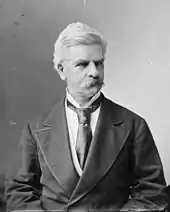

| Preceded by | Emory Washburn |

| Succeeded by | Nathaniel P. Banks |

| President of the Boston Common Council[1] | |

| In office 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Brinley |

| Succeeded by | Alexander H. Rice |

| Member of the Boston Common Council from Ward 4[1] | |

| In office 1851–1853 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henry Joseph Gardner June 14, 1819 Dorchester, Massachusetts |

| Died | July 21, 1892 (aged 73) Milton, Massachusetts |

| Political party | |

| Profession |

|

Born in Dorchester, Gardner was a dry goods merchant from Boston active in the local Whig Party in the early 1850s. With the sudden and secretive rise of the nativist Know Nothings in 1854, Gardner opportunistically[2] repudiated previously-held positions, and joined the movement, winning a landslide victory over Whig Emory Washburn. During his three terms in office the Know Nothing legislatures enacted legislation on a wide-ranging reform agenda, and made several significant changes to the state constitution, including important electoral reforms such as the replacement of majority voting with plurality voting.

The Know Nothing movement began to disintegrate not long after its 1854 victory, dividing over slavery. Gardner won reelection in 1856 only with Republican support, given in exchange for Know Nothing support for the Republican presidential candidate, John Frémont. Republican Nathaniel Prentice Banks easily defeated Gardner in 1857, and the Know Nothing movement effectively dissolved. By 1860 Gardner had left politics and returned to his business interests; he died in relative obscurity.

Early life

Henry Joseph Gardner was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts (then a community separate from Boston) on June 14, 1819, to Henry Gardner and Clarissa Holbrook Gardner.[3] His grandfather, also named Henry Gardner, was a well-respected Harvard graduate, was politically active during the American Revolution and served as the state's treasurer 1774–82.[4] The younger Henry was first educated in private schools in the Boston area, and then attended Phillips Exeter Academy, from which he graduated in 1831.[3] He then attended Bowdoin College,[5] and embarked on a career as a dry goods merchant in Boston, a business in which he remained until 1876. In 1844 he married Helen Cobb of Portland, Maine; they had seven children.[6]

Entry into politics

In 1850 Gardner, politically a Whig, was elected to the Boston City Council, serving until 1853. He was a moderately conservative Websterite Whig who was involved in the state party organization, serving on its central organizing committee. In 1854 he broke with the Whigs over their support of the pro-slavery Kansas-Nebraska Act, and became involved in the nativist Know Nothing movement.[7] This shift in position was fairly radical on Gardner's part, and was viewed by contemporaries and recent historians as politically opportunist.[2][8] Prior to joining the Know Nothings he had not displayed any nativist sentiments, and had even supported an Irish American in a bid to become justice of the peace. He also switched from a moderate Websterite position on slavery to an abolitionist stance, and supported positions on prohibition of alcohol that he had previously opposed. The Whig statesman Edward Everett described Gardner as "a man of some cleverness, but no solidity of character."[2]

The Know Nothing convention in October 1854 chose Gardner as its gubernatorial candidate,[9] in part because his stand on slavery was not as radical as that of Republican candidate Henry Wilson, who was also seeking Know Nothing support. Wilson eventually made a deal with the Know Nothings, withdrawing from the race at the last moment in exchange for Know Nothing support in a United States Senate bid. The campaign was relatively sedate, because both the Whigs and Democrats did not organize large-scale events. The larger parties may have been concerned that rallies would be poorly attended due to defections to the Know Nothings.[7] The aristocratic Whigs fielded incumbent governor Emory Washburn to stand for reelection. They were particularly dismissive of the Know Nothings: one commentator described the Know Nothing ticket as "spavined ministers, lying toothpullers, and buggering priests" who were led by "that rickety vermin of a Henry J. Gardner."[10] Gardner was, however, optimistic, warning one journalist that he would win by a large majority.[10] The election was a landslide: Gardner won 79% of the vote, and the state legislature and Congressional delegation were almost entirely populated by Know Nothings.[2][11]

Governor of Massachusetts

The legislature elected in the Know Nothing sweep was unlike any that preceded it: almost all of its members were new to elected office. The 1855 session was one of the most productive in the state's history, with about 600 bills and resolutions passed. In his inaugural address, Gardner set what he hoped was a tone that would solidify his position has the party leader. The speech focused almost to exclusion on nativist issues, and included hyperbolic claims that the level of immigration was reaching crisis proportions. Gardner notably omitted popular substantive reform issues such as the ten-hour workday, and also avoided the contentious subject of slavery.[12]

Reforms

The 1855 legislature passed a wide variety of reform legislation, most of which Gardner signed. A board of insurance with broad powers of inspection was created; bankruptcy laws were changed to benefit lower-class individuals; imprisonment for debt was abolished. Vaccinations were mandated for all school children, women were given the right to own property on their own, and exempted from responsibility for their husbands' debts; and restrictions were placed on child labor. Schools were desegregated, a reform school for girls was established, and state funding was withdrawn from parochial schools.[13] Cities and towns were authorized to engage in a wide variety of civic improvements, including the building of highways, gas, water, and sewer lines, and public transport facilities such as docks and wharves.[14] One of the major reforms that was not enacted, despite vigorous debate, was legislation calling for a ten-hour workday.[15]

Several amendments to the state constitution were enacted during Gardner's term. All of them originated in the 1853 constitutional convention, whose proposals, although popular, were poorly organized and defeated in a popular referendum. Plurality voting, which had previously been enacted legislatively to apply to federal elections, was extended to state elections. More state executive offices were made elective, including the Governor's Council, Attorney General, Secretary of State, Auditor, and Treasurer. The state's rules for districting were reformed so that they were based on districts drawn by population instead of by towns.[16]

One reform that was immediately a subject of controversy was a harsh prohibition law, which criminalized the service of a glass of grog with a six-month jail sentence. The bill, signed into law by Gardner, was immediately protested, and legislators who passed it were later criticized for charging bar tabs to the state when they traveled.[17]

Nativist issues

Some legislation and executive action was squarely aimed at addressing nativist concerns. So-called "foreign" militia, composed of Irish immigrants, were disbanded, and foreigners were not allowed in police forces or state government jobs.[18] The state deported more than 1,000 allegedly indigent aliens, inciting protest over abuses. One notable case involved the deportation to Liverpool of a woman with an American-born infant without any means of support. Gardner reported that the state saved $100,000 by this process.[19]

The most scandalous aspect of the nativist agenda was the legislature's investigation of alleged abuses in Roman Catholic boarding houses. Joseph Hiss, one of the principal investigators, was reported to have made lewd remarks to nuns in these establishments, and was later found to engage in drinking and the hiring of prostitutes. The scandal received a great deal of press and badly tarnished the Know Nothings.[20]

Slavery

Before Gardner's election, on May 24, 1854, Anthony Burns was arrested in Boston as a fugitive under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.[21] Edward G. Loring, a Suffolk County probate judge who also served as U.S. commissioner of the Circuit Court in Massachusetts, ordered that Burns be forced back into slavery in Virginia, outraging abolitionists and the increasingly antislavery public in Massachusetts. Under the pressure of a public petition campaign spearheaded by William Lloyd Garrison, the legislature passed two Bills of Address, in 1855 and 1856, calling for Judge Loring to be removed from his state office, but in both cases Gardner declined to remove Loring. A third Bill of Address to remove Loring from office was later approved by Gardner's Republican successor, Nathaniel Prentice Banks.[22]

The Know-Nothing legislature also passed, over Gardner's veto, one of the most stringent personal liberty laws, designed to make enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 as difficult for slave claimants as possible.[23] Gardner said that the law would exacerbate relations between North and South, and called for its repeal.[24] Minority parties in the legislature sought to weaken the bill, but its major provisions, including rights of habeas corpus, jury trial, and state-funded defense, survived.[25]

Later elections

In 1855 the national Know Nothing convention split on the subject of slavery. Prominent antislavery Know Nothing supporters in Massachusetts, including Henry Wilson, began another attempt (after having failed in 1854) to form a party with abolition as a major focus.[26] This effort resulted in the formation of the Republican Party, which sought to negotiate with the Know Nothings for a fusion of the two parties. However, Massachusetts Know Nothing leadership refused fusion and Republican leadership refused coalition,[27] with many Republicans skeptical of Gardner's fidelity to the antislavery cause despite his support for fusion.[28] The parties ended up fielding separate slates of candidates, and many Know Nothing politicians and supporters switched allegiance. In the fall election Gardner, running on a strictly nativist platform, garnered 38% of the vote, to the 27% of Republican Julius Rockwell. With the new plurality voting rule in effect, Gardner won the election,[29] but the split (and disaffection in some circles with the Know Nothing agenda) cost him support from former Free Soilers and Democrats.[30] In the 1856 election Gardner benefited from a deal with the Republicans, who refused to run a candidate for governor in exchange for Know Nothing support for their presidential candidate, John C. Frémont. He easily won reelection, although many Republicans voted for a protest candidate instead of supporting him.[31] He attempted to parlay the Republican support into an election to the United States Senate (a matter then decided by the state senate early in its session) replacing Charles Sumner. However, Republican operatives maneuvered the Senate into voting before Gardner's speech opening the 1857 session, and Sumner was easily reelected.[32]

Although the nation was wracked by the Panic of 1857 and Bleeding Kansas, the election in Massachusetts that year hinged on other factors. Gardner was opposed by Republican (and former Know Nothing) Nathaniel Prentice Banks and Democrat Erasmus Beach. Gardner was accused of having become little more than a tool of the formerly Whig industrial interests, and Banks was adept at bringing many former Know Nothings into his camp, most importantly John Z. Goodrich who attested to Banks' strong antislavery credentials. Gardner sought to focus the contests on local issues, but slavery predominated as an issue,[33] and Banks won a comfortable victory.[34]

In 1858 Gardner sought to bring what remained of the Know Nothings into a coalition with the Democrats, but his attempts to find a suitable candidate were unsuccessful. That year's Know Nothing candidate, Amos A. Lawrence, trailed well behind Banks.[35]

Later life

Gardner continued in his dry goods business until 1876, and became an agent for the Massachusetts Life Insurance Company in 1887.[6] He died in Milton, Massachusetts on July 21, 1892. In the 1850s he was recognized by Harvard University with honorary degrees,[36] and he was made a member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company in 1855.[3]

Notes

- "A Catalogue of the City Councils of Boston, 1822-1908, Roxbury, 1846-1867, Charlestown, 1847-1873 and of the Selectmen of Boston, 1634-1822: Also of Various Other Town and Municipal Officers". City of Boston Printing Department. 1909. p. 89. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- Gienapp, p. 136

- Roberts, p. 263

- Palmer, pp. 169–170

- Wright et al, p. 101

- Rand, p. 243

- Anbinder, p. 91

- Mulkern, p. 96

- Anbinder, p. 90

- Mulkern, p. 75

- Anbinder, p. 92

- Mulkern, pp. 95–96, 107

- Formisano, pp. 332–333

- Mulkern, p. 109

- Formisano, p. 340

- Formisano, pp. 334–335

- Mulkern, pp. 101–102

- Formisano, p. 334

- Mulkern, p. 103

- Voss-Hubbard (2002), p. 170

- Von Frank, p. 1

- Voss-Hubbard (1995), pp. 173–174

- Voss-Hubbard (2002), p. 172

- Voss-Hubbard (1995), p. 173

- Voss-Hubbard (1995), pp. 175–177

- Duberman, pp. 364–365

- Duberman, p. 366

- Duberman, p. 367

- Duberman, pp. 368–369

- Baum, pp. 966–967

- Baum, pp. 968–969

- Donald. pp. 320–322

- Stampp, p. 242

- Hollandsworth, p. 35

- Baum, pp. 972–973

- Annual Report of Harvard University, 1854–1855, p. 53

References

- Anbinder, Tyler (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507233-4. OCLC 55718937.

- Baum, Dale (March 1978). "Know-Nothingism and the Republican Majority in Massachusetts: The Political Realignment of the 1850s". The Journal of American History. 64 (4): 959–986. doi:10.2307/1890732. JSTOR 1890732.

- Donald, David (1960). Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15633-0. OCLC 19357352.

- Duberman, Martin (September 1961). "Some Notes on the Beginnings of the Republican Party in Massachusetts". The New England Quarterly. 34 (3): 364–370. doi:10.2307/362933. JSTOR 362933.

- Formisano, Ronald (1983). The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503509-4. OCLC 18429354.

- Gienapp, William (1988). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802114-8. OCLC 437173404.

- Hollandsworth, James (1998). Pretense of Glory: The Life of General Nathaniel p. Banks. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2293-9.

- Harvard University (1856). Annual Report of Harvard University, 1854–1855. Harvard University. OCLC 8152872.

- Mulkern, John (1990). The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-071-6. OCLC 20594513.

- Palmer, Joseph (1864). Necrology of Alumni of Harvard College, 1851–52 to 1862–63. Boston: John Wilson and Son. p. 170. OCLC 1344448.

- Rand, John Clark, ed. (1890). One of a Thousand: A Series of Biographical Sketches of One Thousand Representative Men Resident in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, A.D. 1888–89. Boston: First National Publishing Co. p. 243. OCLC 1306357.

- Roberts, Oliver (1898). History of the Military Company of the Massachusetts, Volume 3. Boston: A. Mudge & Son. OCLC 1394719.

- Stampp, Kenneth (1990). America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503902-3. OCLC 21030400.

- Von Frank, Albert (1998). The Trials of Anthony Burns. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03954-4. OCLC 37721476.

- Voss-Hubbard, Mark (August 1995). "The Political Culture of Emancipation: Morality, Politics, and the State in Garrisonian Abolitionism, 1854–1863". Journal of American Studies. 29 (2): 159–184. doi:10.1017/S0021875800020806. JSTOR 27555920.

- Voss-Hubbad, Mark (2002). Beyond Party: Cultures of Antipartisanship in Northern Politics Before the Civil War. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7779-7. OCLC 51493536.

- Wright, Frank (1888). Parker, Arthur; Kimball, Frank (eds.). History of the Bowdoin College Alumni Association of Boston and Vicinity, 1868–87. Salem, MA: Salem Press. OCLC 79014812.