Henry IV of England

Henry IV (c. April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. Henry’s grandfather Edward III had begun the Hundred Years War by claiming the French throne in opposition to the House of Valois, a claim that Henry would continue during his reign. However, unlike his forebears, Henry was the first English ruler since the Norman Conquest, over three hundred years prior, whose mother tongue was English rather than French.[4]

| Henry IV | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| King of England | |

| Reign | 30 September 1399 – 20 March 1413 |

| Coronation | 13 October 1399[2] |

| Predecessor | Richard II |

| Successor | Henry V |

| Born | c. April 1367[3] Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 20 March 1413 (aged 45) Jerusalem Chamber, Westminster, England |

| Burial | Canterbury Cathedral, Kent, England |

| Spouses | |

| Issue more... | |

| House | Lancaster |

| Father | John of Gaunt |

| Mother | Blanche of Lancaster |

| Signature |  |

Henry was the son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, himself the son of Edward III.[2] Gaunt was a powerful figure in England during the reign of his own nephew, Richard II. Henry was involved in the 1388 revolt of Lords Appellant against Richard, but he was not punished. However, he was exiled from court in 1398. After Gaunt died in 1399, Richard blocked Henry's inheritance of his father's duchy. That year, Henry rallied a group of supporters, overthrew and imprisoned Richard II, and usurped the throne, actions that later would lead to what is termed the Wars of the Roses and a more stabilized monarchy.

As king, Henry faced a number of rebellions, most seriously those of Owain Glyndŵr, the last Welsh Prince of Wales, and the English knight Henry Percy (Hotspur), who was killed in the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. Henry IV had six children from his first marriage to Mary de Bohun, while his second marriage to Joan of Navarre was childless. Henry and Mary's eldest son, Henry of Monmouth, assumed the reins of government in 1410 as the king's health worsened. Henry IV died in 1413, and his son succeeded him as Henry V.

Early life

Henry was born at Bolingbroke Castle, in Lincolnshire, to John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster.[2] His epithet "Bolingbroke" was derived from his birthplace. Gaunt was the third son of King Edward III. Blanche was the daughter of the wealthy royal politician and nobleman Henry, Duke of Lancaster. Gaunt enjoyed a position of considerable influence during much of the reign of his own nephew, King Richard II. Henry's elder sisters were Philippa, Queen of Portugal, and Elizabeth, Duchess of Exeter. His younger half-sister Katherine, Queen of Castile, was Gaunt's daughter with his second wife, Constance of Castile. Henry also had four half-siblings born of Katherine Swynford, originally his sisters' governess, then his father's longstanding mistress and later third wife. These illegitimate (although later legitimized) children were given the surname Beaufort from their birthplace at the Château de Beaufort in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France.[5]

Henry's relationship with his stepmother Katherine Swynford was a positive one, but his relationship with the Beauforts varied. In his youth, he seems to have been close to all of them, but rivalries with Henry and Thomas Beaufort proved problematic after 1406. Ralph Neville, 4th Baron Neville, married Henry's half-sister Joan Beaufort. Neville remained one of his strongest supporters, and so did his eldest half-brother John Beaufort, even though Henry revoked Richard II's grant to John of a marquessate. Katherine Swynford's son from her first marriage, Thomas, was another loyal companion. Thomas Swynford was Constable of Pontefract Castle, where Richard II is said to have died.

Conflict at court

Relationship with Richard II

Henry experienced a more inconsistent relationship with King Richard II than his father had. First cousins and childhood playmates, they were admitted together as knights of the Order of the Garter in 1377, but Henry participated in the Lords Appellants' rebellion against the king in 1387.[6] After regaining power, Richard did not punish Henry, although he did execute or exile many of the other rebellious barons. In fact, Richard elevated Henry from Earl of Derby to Duke of Hereford.

Henry spent the full year of 1390 supporting the unsuccessful siege of Vilnius (capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) by Teutonic Knights with 70 to 80 household knights.[7] During this campaign, he bought captured Lithuanian women and children and took them back to Königsberg to be converted, despite Lithuanians being baptised by Polish priests for a decade at this point.[8]

Henry's second expedition to Lithuania in 1392 illustrates the financial benefits to the Order of these guest crusaders. His small army consisted of over 100 men, including longbow archers and six minstrels, at a total cost to the Lancastrian purse of £4,360. Despite the efforts of Henry and his English crusaders, two years of attacks on Vilnius proved fruitless. In 1392–93 Henry undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, where he made offerings at the Holy Sepulchre and at the Mount of Olives.[9] Later he vowed to lead a crusade to 'free Jerusalem from the infidel', but he died before this could be accomplished.[10]

The relationship between Henry and Richard met with a second crisis. In 1398, a remark regarding Richard II's rule by Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk, was interpreted as treason by Henry who reported it to the king.[11] The two dukes agreed to undergo a duel of honour (called by Richard II) at Gosford Green near Caludon Castle, Mowbray's home in Coventry. Yet before the duel could take place, Richard decided to banish Henry from the kingdom (with the approval of Henry's father, John of Gaunt), although it is unknown where he spent his exile, to avoid further bloodshed. Mowbray was exiled for life.[12]

John of Gaunt died in February 1399.[12] Without explanation, Richard cancelled the legal documents that would have allowed Henry to inherit Gaunt's land automatically. Instead, Henry would be required to ask for the lands from Richard.[13]

Accession

After some hesitation, Henry met the exiled Thomas Arundel, former archbishop of Canterbury, who had lost his position because of his involvement with the Lords Appellant.[13] Henry and Arundel returned to England while Richard was on a military campaign in Ireland. With Arundel as his advisor, Henry began a military campaign, confiscating land from those who opposed him and ordering his soldiers to destroy much of Cheshire. Henry initially announced that his intention was to reclaim his rights as Duke of Lancaster, though he quickly gained enough power and support to have himself declared King Henry IV, imprison King Richard (who died in prison, most probably forcibly starved to death[14]) and bypass Richard's 7-year-old heir-presumptive, Edmund de Mortimer, 5th Earl of March.[15]

Henry's coronation, on 13 October 1399 at Westminster Abbey,[16] may have marked the first time since the Norman Conquest that the monarch made an address in English.

In January 1400, the new king quashed a rebellion by Richard's supporters, who plotted to assassinate him. It was known as the Epiphany Rising. Henry was forewarned and raised an army in London, at which the conspirators fled. They were apprehended and executed without trial.

Reign

Henry procured an Act of Parliament to ordain that the Duchy of Lancaster would remain in the personal possession of the reigning monarch. The Barony of Halton was vested in that dukedom.[17]

Henry consulted with Parliament frequently, but was sometimes at odds with the members, especially over ecclesiastical matters. On Arundel's advice, Henry obtained from Parliament the enactment of De heretico comburendo in 1401, which prescribed the burning of heretics, an act done mainly to suppress the Lollard movement.[18][19] In 1410, Parliament suggested confiscating church land. Henry refused to attack the Church that had helped him to power, and the House of Commons had to beg for the bill to be struck off the record.[20]

Rebellions

_obverse.jpg.webp)

Henry spent much of his reign defending himself against plots, rebellions, and assassination attempts. Henry's first major problem as monarch was what to do with the deposed Richard. After the early assassination plot was foiled in January 1400, Richard died in prison aged 33, probably of starvation on Henry's order.[21] Some chroniclers claimed that the despondent Richard had starved himself,[22] which would not have been out of place with what is known of Richard's character. Though council records indicate that provisions were made for the transportation of the deposed king's body as early as 17 February, there is no reason to believe that he did not die on 14 February, as several chronicles stated. It can be positively said that he did not suffer a violent death, for his skeleton, upon examination, bore no signs of violence; whether he did indeed starve himself or whether that starvation was forced upon him are matters for lively historical speculation.[22]

After his death, Richard's body was put on public display in the old St Paul's Cathedral, both to prove to his supporters that he was truly dead and also to prove that he had not suffered a violent death. This did not stop rumours from circulating for years after that he was still alive and waiting to take back his throne, and that the body displayed was that of Richard's chaplain, a priest named Maudelain, who greatly resembled him. Henry had the body discreetly buried in the Dominican Priory at Kings Langley, Hertfordshire, where he remained until King Henry V brought the body back to London and buried it in the tomb that Richard had commissioned for himself in Westminster Abbey.[23]

Rebellions continued throughout the first 10 years of Henry's reign, including the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, who declared himself Prince of Wales in 1400, and the rebellions led by Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, from 1403. The first Percy rebellion ended in the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403 with the death of the earl's son Henry, a renowned military figure known as "Hotspur" for his speed in advance and readiness to attack. Also in this battle, Henry IV's eldest son, Henry of Monmouth, later King Henry V, was wounded by an arrow in his face. He was cared for by royal physician John Bradmore. Despite this, the Battle of Shrewsbury was a royalist victory. Monmouth's military ability contributed to the king's victory (though Monmouth seized much effective power from his father in 1410).

In the last year of Henry's reign, the rebellions picked up speed. "The old fable of a living Richard was revived", notes one account, "and emissaries from Scotland traversed the villages of England, in the last year of Henry's reign, declaring that Richard was residing at the Scottish Court, awaiting only a signal from his friends to repair to London and recover his throne."

A suitable-looking impostor was found and King Richard's old groom circulated word in the city that his master was alive in Scotland. "Southwark was incited to insurrection" by Sir Elias Lyvet (Levett) and his associate Thomas Clark, who promised Scottish aid in carrying out the insurrection. Ultimately, the rebellion came to naught. Lyvet was released and Clark thrown into the Tower of London.[24]

Foreign relations

Early in his reign, Henry hosted the visit of Manuel II Palaiologos, the only Byzantine emperor ever to visit England, from December 1400 to February 1401 at Eltham Palace, with a joust being given in his honour. Henry also sent monetary support with Manuel upon his departure to aid him against the Ottoman Empire.[26]

In 1406, English pirates captured the future James I of Scotland, aged eleven, off the coast of Flamborough Head as he was sailing to France.[27] James was delivered to Henry IV and remained a prisoner for the rest of Henry's reign.

Final illness and death

The later years of Henry's reign were marked by serious health problems. He had a disfiguring skin disease and, more seriously, suffered acute attacks of a grave illness in June 1405; April 1406; June 1408; during the winter of 1408–09; December 1412; and finally a fatal bout in March 1413. In 1410, Henry had provided his royal surgeon Thomas Morstede with an annuity of £40 p.a. which was confirmed by Henry V immediately after his succession. This was so that Morstede would "not be retained by anyone else".[28] Medical historians have long debated the nature of this affliction or afflictions. The skin disease might have been leprosy (which did not necessarily mean precisely the same thing in the 15th century as it does to modern medicine), perhaps psoriasis, or a different disease. The acute attacks have been given a wide range of explanations, from epilepsy to a form of cardiovascular disease.[29] Some medieval writers felt that he was struck with leprosy as a punishment for his treatment of Richard le Scrope, Archbishop of York, who was executed in June 1405 on Henry's orders after a failed coup.[30]

According to Holinshed, it was predicted that Henry would die in Jerusalem, and Shakespeare's play repeats this prophecy. Henry took this to mean that he would die on crusade. In reality, he died in the Jerusalem Chamber in the abbot's house of Westminster Abbey, on 20 March 1413 during a convocation of Parliament.[31] His executor, Thomas Langley, was at his side.

Burial

.jpg.webp)

Despite the example set by most of his recent predecessors, Henry and his second wife, Joan, were not buried at Westminster Abbey but at Canterbury Cathedral, on the north side of Trinity Chapel and directly adjacent to the shrine of St Thomas Becket. Becket's cult was then still thriving, as evidenced in the monastic accounts and in literary works such as The Canterbury Tales, and Henry seemed particularly devoted to it, or at least keen to be associated with it. Reasons for his interment in Canterbury are debatable, but it is highly likely that Henry deliberately associated himself with the martyr saint for reasons of political expediency, namely, the legitimisation of his dynasty after seizing the throne from Richard II.[32] Significantly, at his coronation, he was anointed with holy oil that had reportedly been given to Becket by the Virgin Mary shortly before his death in 1170;[33][34] this oil was placed inside a distinct eagle-shaped container of gold. According to one version of the tale, the oil had then passed to Henry's maternal grandfather, Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster.[35]

Proof of Henry's deliberate connection to Becket lies partially in the structure of the tomb itself. The wooden panel at the western end of his tomb bears a painting of the martyrdom of Becket, and the tester, or wooden canopy, above the tomb is painted with Henry's personal motto, 'Soverayne', alternated by crowned golden eagles. Likewise, the three large coats of arms that dominate the tester painting are surrounded by collars of SS, a golden eagle enclosed in each tiret.[36] The presence of such eagle motifs points directly to Henry's coronation oil and his ideological association with Becket. Sometime after Henry's death, an imposing tomb was built for him and his queen, probably commissioned and paid for by Queen Joan herself.[37] Atop the tomb chest lie detailed alabaster effigies of Henry and Joan, crowned and dressed in their ceremonial robes. Henry's body was evidently well embalmed, as an exhumation in 1832 established, allowing historians to state with reasonable certainty that the effigies do represent accurate portraiture.[38][39]

Titles and arms

Titles

- Styled Earl of Derby (1377–97)[2][40]

- Earl of Northampton and Hereford (22 December 1384 – 30 September 1399)[2][41]

- Duke of Hereford (29 September 1397 – 30 September 1399)[2][41]

- Duke of Lancaster (3 February – 30 September 1399)[2][41]

- King of England and Lord of Ireland (30 September 1399 – 20 March 1413)[2]

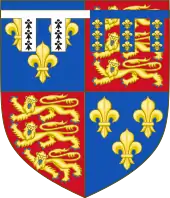

Arms

Before his father's death in 1399, Henry bore the arms of the kingdom, differenced by a label of five points ermine. After his father's death, the difference changed to a label of five points per pale ermine and France.[42]

.svg.png.webp)

Coat of arms as Duke of Hereford

Coat of arms as Duke of Hereford Coat of arms as Duke of Hereford and Lancaster

Coat of arms as Duke of Hereford and Lancaster Coat of arms as 3rd Earl of Derby, KG

Coat of arms as 3rd Earl of Derby, KG.svg.png.webp) Henry's achievement as king with the old arms of France

Henry's achievement as king with the old arms of France.svg.png.webp) Royal achievement as king

Royal achievement as king

Genealogy

| English royal families in the Wars of the Roses |

|---|

|

Dukes (except Aquitaine) and Princes of Wales are noted, as are the monarchs' reigns.

Individuals with red dashed borders are Lancastrians and blue dotted borders are Yorkists. Some changed sides and are represented with a solid thin purple border. Monarchs have a rounded-corner border. See also Family tree of English monarchs |

Marriages and issue

First marriage: Mary de Bohun

The date and venue of Henry's first marriage to Mary de Bohun (died 1394) are uncertain[2] but her marriage licence, purchased by Henry's father John of Gaunt in June 1380, is preserved at the National Archives. The accepted date of the ceremony is 5 February 1381, at Mary's family home of Rochford Hall, Essex.[31] The near-contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart reports a rumour that Mary's sister Eleanor de Bohun kidnapped Mary from Pleshey Castle and held her at Arundel Castle, where she was kept as a novice nun; Eleanor's intention was to control Mary's half of the Bohun inheritance (or to allow her husband, Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, to control it).[43] There Mary was persuaded to marry Henry. They had six children:[lower-alpha 1]

| Name | Arms | Blazon |

|---|---|---|

| Henry V of England (1386–1422), 1st son[2] | .svg.png.webp) |

Arms of King Henry IV: France modern quartering Plantagenet |

| Thomas, Duke of Clarence (1387–1421), 2nd son, who married Margaret Holland, widow of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, and daughter of Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent, without progeny.[2] |  |

Arms of King Henry IV with a label of three points argent each charged with three ermine spots and a canton gules for difference |

| John, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435), 3rd son, who married twice: firstly to Anne of Burgundy (d.1432), daughter of John the Fearless, without progeny. Secondly to Jacquetta of Luxembourg, without progeny.[2] |  |

Arms of King Henry IV with a label of five points per pale ermine and France for difference |

| Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390–1447), 4th son, who married twice but left no surviving legitimate progeny: firstly to Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut and Holland (d.1436), daughter of William VI, Count of Hainaut. Through this marriage Gloucester assumed the title "Count of Holland, Zeeland and Hainault". Secondly to Eleanor Cobham, his mistress.[2] |  |

Arms of King Henry IV with bordure argent for difference |

| Blanche of England (1392–1409) married in 1402 Louis III, Elector Palatine[44][2] | ||

| Philippa of England (1394–1430) married in 1406 Eric of Pomerania, king of Denmark, Norway and Sweden.[2] | ||

Henry had four sons from his first marriage, which was undoubtedly a clinching factor in his acceptability for the throne. By contrast, Richard II had no children and Richard's heir-presumptive Edmund Mortimer was only seven years old. The only two of Henry's six children who produced legitimate children to survive to adulthood were Henry V and Blanche, whose son, Rupert, was the heir to the Electorate of the Palatinate until his death at 20. All three of his other sons produced illegitimate children. Henry IV's male Lancaster line ended in 1471 during the War of the Roses, between the Lancastrians and the Yorkists, with the deaths of his grandson Henry VI and Henry VI's son Edward, Prince of Wales.

Second marriage: Joan of Navarre

Mary de Bohun died in 1394, and on 7 February 1403 Henry married Joan, the daughter of Charles II of Navarre, at Winchester. She was the widow of John IV, Duke of Brittany (known in traditional English sources as John V),[45] with whom she had 9 children; however, her marriage to King Henry produced no surviving children.[2] In 1403, Joan of Navarre gave birth to stillborn twins fathered by King Henry IV, which was the last pregnancy of her life. Joan was 35 years old at the time.

See also

- Cultural depictions of Henry IV of England

- Naish Priory in Somerset contains corbelled heads of Henry IV and Joanna celebrating their marriage, at the manor of Mary de Bohun's late and powerful great-aunt, Margaret de Bohun

- List of earls in the reign of Henry IV of England

- Mouldwarp

Notes

- The idea that Henry and Mary had a child Edward who was born and died in April 1382 is based on a misreading of an account which was published in an erroneous form by JH Wylie in the 19th century. It missed a line which made clear that the boy in question was the son of Thomas of Woodstock. The attribution of the name Edward to this boy is conjecture based on the fact that Henry was the grandson of Edward III and idolised his uncle Edward of Woodstock yet did not call any of his sons Edward. However, there is no evidence that there was any child at this time (when Mary de Bohun was 12), let alone that he was called Edward. See appendix 2 in Ian Mortimer's book The Fears of Henry IV.

References

- Mortimer 2007, p. 176.

- Weir 2008, p. 124.

- Mortimer, I. (6 December 2006). "Henry IV's date of birth and the royal Maundy" (PDF). Historical Research. 80 (210): 567–576. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2006.00403.x. ISSN 0950-3471. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2019.

- Janvrin & Rawlinson 2016, p. 16.

- Armitage-Smith 1905, p. 318.

- Bevan 1994, p. 6, 13.

- Given-Wilson 2016, pp. 66–68.

- Given-Wilson 2016, p. 69.

- Bevan 1994, p. 32.

- Bevan 1994, p. 1.

- A. Lyon, Constitutional History of the UK, London – Sydney – Portland, 2003, p. 122 Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- H. Barr, Signes and Sothe: Language in the Piers Plowman Tradition, Cambridge, 1994, p. 146.

- Bevan 1994, p. 51.

- Bevan 1994, p. 72.

- Bevan 1994, p. 66.

- Bevan 1994, p. 67.

- Nickson 1887, pp. 146–147.

- Somerset, Fiona; Havens, Jill C.; Derrick G. Pitard (2003). Lollards and Their Influence in Late Medieval England. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-8511-5995-9. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Dodd, Gwilym; Biggs, Douglas (2008). The Reign of Henry IV: Rebellion and Survival, 1403–1413. Boydell & Brewer. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-9031-5323-9. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Jones, Terry & Alan Ereira (2004). Terry Jones' Medieval Lives (hardcover ed.). BBC Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-5634-8793-7. OL 7852111M.

- Bevan, Bryan (2016). Henry IV. p. 72: "Suggestive evidence that Richard's murder was carefully planned is contained among the exchequer payments. 'To William Loveney, Clerk of the Great Wardrobe, sent to Pontefract Castle on secret business by order of the King (Henry IV).'"

- Tuck, Anthony (2004). "Richard II (1367–1400)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Burden, Joel (2003). "How Do You Bury a Deposed King?". In Dodd, Gwilym; Biggs, Douglas (eds.). Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399–1406. York: York Medieval Press. pp. 35–53.

- Doran, John (1860). The Book of the Princes of Wales, Heirs to the Crown of England. Richard Bentley. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "St Alban's chronicle". p. 245. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Dennis, George T. (1977). The Letters of Manuel II Palaeologus. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Trustees for Harvard University. Letter 38. ISBN 978-0-8840-2068-4.

- Balfour-Melville, Evan Whyte Melville (1936). James I, King of Scots, 1406–1437. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-5989-1630-3.

- Beck, Theodore (1974). Cutting Edge: Early History of the Surgeons of London. Lund Humphries Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8533-1366-3.

- McNiven 1985, pp. 747–772.

- Swanson, Robert N. (1995). Religion and Devotion in Europe, c. 1215 – c. 1515. Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-5213-7950-2. OL 1109807M.

- Brown & Summerson 2010.

- Wilson 1990, pp. 181–190.

- Walsingham, Thomas. Taylor, John; et al. (eds.). The St Albans Chronicle: The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham. Vol. II, 1394–1422. Translated by Taylor, John. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 237.

- Legg, L.G.W., ed. (1901), "Pope John XXII to King Edward II of England, 2 June 1318", English Coronation Records, London: Archibald Constable & Co., pp. 73–75, OCLC 2140947, OL 24187986M

- Walsingham, pp. 237–241.

- Wilson 1990, pp. 186–189.

- Wilson, Christopher (1995). Collinson, Patrick; et al. (eds.). The Medieval Monuments. pp. 451–510.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Woodruff, C. Eveleigh; Danks, William (1912). Memorials of the Cathedral and Priory of Christ in Canterbury. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. pp. 192–194.

- Antiquary (10 May 1902). "Exhumation of Henry IV". Notes and Queries. 9th series. 9 (228): 369. doi:10.1093/nq/s9-IX.228.369c.

- "Henry IV | Biography, Accomplishments, & Facts". Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Cokayne et al. 1926, p. 477.

- Velde, Francois R. "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family". Heraldica.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Johnes, Thomas; Froissart, Jean (1806). Chronicles of England, France and Spain. Vol. 5. London: Longman. p. 242. OCLC 465942209.; Strickland, Agnes (1840). Lives of the queens of England from the Norman conquest with anecdotes of their courts. Vol. 3. London: Henry Colborn. p. 144. OCLC 459108616.

- Panton 2011, p. 74.

- Jones, Michael (1988). The Creation of Brittany. London: Hambledon Press. p. 123. ISBN 090762880X – via Internet Archive.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 554. ISBN 978-1-4499-6638-6.

- Mortimer 2007, p. 372.

Works cited

- Armitage-Smith, Sydney (1905). John of Gaunt. Charles Scribner's Sons. OL 32573643M.

- Bevan, Bryan (1994). Henry IV. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312116969. OL 1237370M.

- Brown, Alfred Lawson; Summerson, H. (2010). "Henry IV [known as Henry Bolingbroke]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12951. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cokayne, George Edward; Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. A.; Warrand, Duncan; Lord Howard de Walden, eds. (1926). The Complete Peerage. Vol. VI (2nd ed.). London: St Catherine Press.

- Janvrin, Isabelle; Rawlinson, Catherine (2016). The French in London: From William the Conqueror to Charles de Gaulle. Translated by Emily Read. Wilmington Square Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-908524-65-2.

- Given-Wilson, Chris (2016). Henry IV. English Monarchs series. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15419-1.

- McNiven, Peter (1985). "The Problem of Henry IV's Health, 1405–1413". English Historical Review. 100.

- Mortimer, Ian (2007). The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-made King. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-07300-4. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Nickson, Charles (1887), History of Runcorn, London and Warrington: Mackie & Co., OCLC 5389146

- Panton, Kenneth J. (2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press.

- Weir, Alison (2008). Britain's Royal Family. ISBN 978-0099539735. OL 24083871M.

- Wilson, Christopher (1990). Fernie, Eric; Crossley, Paul (eds.). The Tomb of Henry IV and the Holy Oil of St Thomas of Canterbury. OL 1875648M.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Watson, G. W. (1896). "The Seize Quartiers of the Kings and Queens of England". In H. W. Forsyth Harwood (ed.). The Genealogist. New Series. Vol. 12. Exeter: William Pollard & Co.

External links

- Henry IV at the official website of the British monarchy

- Henry IV at BBC History

- Portraits of King Henry IV at the National Portrait Gallery, London