Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives or Mount Olivet (Hebrew: הַר הַזֵּיתִים, romanized: Har ha-Zeitim; Arabic: جبل الزيتون, romanized: Jabal az-Zaytūn; both lit. 'Mount of Olives'; in Arabic also الطور, Aṭ-Ṭūr, 'the Mountain') is a mountain ridge in East Jerusalem, east of and adjacent to Jerusalem's Old City.[1] It is named for the olive groves that once covered its slopes. Atop the hill lies the Palestinian neighbourhood of At-Tur, a former village that is now part of East Jerusalem. The southern part of the mount was the Silwan necropolis, attributed to the elite of the ancient Kingdom of Judah.[2] The western slopes of the mount, those facing Jerusalem, have been used as a Jewish cemetery for over 3,000 years and holds approximately 150,000 graves, making it central in the tradition of Jewish cemeteries.[3]

| Mount of Olives | |

|---|---|

| Mount Olivet | |

Aerial photograph of the Mount of Olives | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 826 m (2,710 ft) |

| Coordinates | 31°46′42″N 35°14′38″E |

| Naming | |

| Native name | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Jerusalem |

| Parent range | Judean Mountains |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Road |

Several key events in the life of Jesus, as related in the Gospels, took place on the Mount of Olives, and in the Acts of the Apostles it is described as the place from which Jesus ascended to heaven. Because of its association with both Jesus and Mary, the mount has been a site of Christian worship since ancient times and is today a major site of pilgrimage for Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and Protestants.

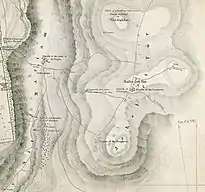

Geography and geology

The Mount of Olives is one of three peaks of a mountain ridge which runs for 3.5 kilometres (2.2 miles) just east of the Old City across the Kidron Valley, in this area called the Valley of Josaphat. The peak to its north is Mount Scopus, at 826 metres (2,710 feet), while the peak to its south is the Mount of Corruption, at 747 m (2,451 ft). The highest point on the Mount of Olives is At-Tur, at 818 m (2,684 ft).[5] The ridge acts as a watershed, and its eastern side is the beginning of the Judean Desert.

The ridge is formed of oceanic sedimentary rock from the Late Cretaceous and contains a soft chalk and a hard flint. While the chalk is easily quarried, it is not a suitable strength for construction and features many man-made burial caves.

History

.jpg.webp)

From Biblical times until the present, Jews have been buried on the Mount of Olives. The necropolis on the southern ridge, the location of the modern village of Silwan, was the burial place of Jerusalem's most important citizens in the period of the Biblical kings.[2]

The religious ceremony marking the start of a new month was held on the Mount of Olives during the Second Temple period.[6] During the time of the Roman procurator Antonius Felix (52–60 CE), a Jewish prophetic figure known as "the Egyptian" gathered his followers atop the Mount of Olives in preparation for an invasion of the city or in the belief that he would cause the walls of Jerusalem to fall, allowing them to enter (depending on the version). This group was crushed by the Romans. While "the Egyptian" managed to flee, many of his followers were killed or taken captive, and the remainder escaped.[7][8]

Roman soldiers from the 10th Legion camped on the mount during the Siege of Jerusalem in the year 70 AD. After the destruction of the Second Temple, Jews celebrated the festival of Sukkot on the Mount of Olives. They made pilgrimages to the Mount of Olives because it was 80 meters higher than the Temple Mount and offered a panoramic view of the Temple site. It became a traditional place for lamenting the Temple's destruction, especially on Tisha B'Av.[6] In 1481, an Italian Jewish pilgrim, Meshullam of Volterra, wrote: "And all the community of Jews, every year, goes up to Mount Zion on the day of Tisha B'Av to fast and mourn, and from there they move down along Yoshafat Valley and up to Mount of Olives. From there they see the whole Temple (the Temple Mount) and there they weep and lament the destruction of this House."[9]

In 1189, in the wake of the 1187 Battle of Hattin and reconquest of the land by Saladin, the sultan gave the Mount to two of his commanders.

In the mid-1850s, the villagers of Silwan were paid £100 annually by the Jews in an effort to prevent the desecration of graves on the mount.[10]

Prime Minister of Israel Menachem Begin asked to be buried on the Mount of Olives near the graves of Etzel members Meir Feinstein and Moshe Barazani, rather than Mount Herzl national cemetery.[11]

Status since 1948

.jpg.webp)

The armistice agreement signed by Israel and Jordan following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War called for the establishment of a Special Committee to negotiate developments including "free access to the holy sites and cultural institutions and use of the cemetery on the Mount of Olives". However, during the 19 years the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank lasted, the committee was not formed. Non-Israeli Christian pilgrims were allowed to visit the mount, but Jews of all countries and most non-Jewish Israeli citizens were barred from entering Jordan and therefore were unable to travel to the area.[12][13][14]

By the end of 1949, and throughout the Jordanian rule of the site, some Arab residents uprooted tombstones and plowed the land in the cemeteries, and an estimated 38,000 tombstones were damaged in total. During this period, a road was paved through the cemetery, in the process destroying graves including those of famous persons.[15] In 1964, the Intercontinental Hotel was built at the summit of the mount. Graves were also demolished for parking lots and a filling station[16] and were used in latrines at a Jordanian Army barracks.[17][18][19][20] The United Nations did not condemn the Jordanian government for these actions.[21]

State of Israel

Following the 1967 Six-Day War restoration work was done and the cemetery was reopened for burials. Israel's 1980 unilateral annexation of East Jerusalem was condemned as a violation of international law and ruled null and void by the UN Security Council in UNSC Resolution 478.

Tombs in the Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery have been prone to vandalism, among them the tombs of the Gerrer Rebbe and Menachem Begin.[22][23][24][25]

On 6 November 2010, an international watch-committee was set up by Diaspora Jews with the aim of reversing the desecration of the Jewish cemetery. According to one of the founders, the initiative was triggered by witnessing tombstones that were wrecked with "the kind of maliciousness that defies the imagination."[25]

Religious significance

David and Absalom

The Mount of Olives is first mentioned in connection with David's flight from Absalom (II Samuel 15:30): "And David went up by the ascent of the Mount of Olives, and wept as he went up." The ascent was probably east of the City of David, near the village of Silwan.[1]

Site of "the glory of the Lord"

The sacred character of the mount is alluded to in the Book of Ezekiel (11:23): "And the glory of the Lord went up from the midst of the city, and stood upon the mountain which is on the east side of the city."[1]

"Mount of Corruption"

The biblical designation Mount of Corruption, or in Hebrew Har HaMashchit (I Kings 11:7–8), derives from the idol worship there, begun by King Solomon building altars to the gods of his Moabite and Ammonite wives on the southern peak, "on the mountain which is before (east of) Jerusalem" (1 Kings 11:7), just outside the limits of the holy city. This site was known for idol worship throughout the First Temple period, until king of Judah, Josiah, finally destroyed "the high places that were before Jerusalem, to the right of Har HaMashchit..."(II Kings 23:13)

Apocalypse, resurrection, and burials

An apocalyptic prophecy in the Book of Zechariah states that YHWH will stand on the Mount of Olives and the mountain will split in two, with one half shifting north and one half shifting south (Zechariah 14:4). According to the Masoretic Text, people will flee through this newly formed valley to a place called Azal (Zechariah 14:5). The Septuagint (LXX) has a different reading of Zechariah 14:5 stating that a valley will be blocked up as it was blocked up during the earthquake during King Uzziah's reign. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus mentions in Antiquities of the Jews that the valley in the area of the King's Gardens was blocked up by landslide rubble during Uzziah's earthquake.[26] Israeli geologists Wachs and Levitte identified the remnant of a large landslide on the Mount of Olives directly adjacent to this area.[27] Based on geographic and linguistic evidence, Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, a 19th-century linguist and archeologist in Palestine, theorized that the valley directly adjacent to this landslide is Azal.[28] This evidence accords with the LXX reading of Zechariah 14:5, which states that the valley will be blocked up as far as Azal. The valley he identified (which is now known as Wady Yasul in Arabic, and Nahal Etzel in Hebrew) lies south of both Jerusalem and the Mount of Olives.

Many Jews have wanted to be buried on the Mount of Olives since antiquity, based on the Jewish tradition (from the Biblical verse Zechariah 14:4) that when the Messiah comes, the resurrection of the dead will begin there.[29] There are an estimated 150,000 graves on the Mount. Notable rabbis buried on the mount include Chaim ibn Attar and others from the 15th century to the present day. Tradition wrongly identifies Roman-period tombs at the foot of the mount as those of Zechariah and Absalom, and a burial complex of the same period on the upper slope as the Tomb of the Prophets Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi.

New Testament references

The Mount of Olives is frequently mentioned in the New Testament[30] as part of the route from Jerusalem to Bethany and the place where Jesus stood when he wept over Jerusalem (an event known as Flevit super illam in Latin).

Jesus is said to have spent time on the mount, teaching and prophesying to his disciples (Matthew 24–25), including the Olivet discourse, returning after each day to rest (Luke 21:37, and John 8:1 in the additional section of John's Gospel known as the Pericope Adulterae), and also coming there on the night of his betrayal.[31] At the foot of the Mount of Olives lies the Garden of Gethsemane. The New Testament tells how Jesus and his disciples sang together – "When they had sung the hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives" Gospel of Matthew 26:30. Jesus ascended to heaven from the Mount of Olives according to Acts 1:9–12.

Gnostic references

Again, the story of Jesus with his disciples on the Mount of Olives can be found in the Gnostic text Pistis Sophia, dated around the 3rd to 4th century CE.[32]

Landmarks

Landmarks at the top of the Mount of Olives include the Augusta Victoria Hospital with the Lutheran Church of the Ascension and its massive 50-metre (160 ft) bell tower, the Russian Orthodox Church of the Ascension with its tall and slender bell tower, the Mosque or Chapel of the Ascension, the Church of the Pater Noster, and the Seven Arches Hotel. On the western slope are the historic Jewish cemetery, the Tomb of the Prophets, the Catholic Church of Dominus Flevit, and the Russian Orthodox Church of Mary Magdalene. At the foot of the mount, where it meets the Kidron Valley, there is the Garden of Gethsemane with the Church of All Nations. Within the Kidron Valley itself are the Tomb of the Virgin Mary, the Grotto of Gethsemane, and the nearby tomb of the medieval historian Mujir ed-Din, and further south are the tombs of Absalom (Hebrew name: Yad Avshalom), the Hezir priestly family and of Zechariah. At the northern margin of Mount Olivet stand the Mormon University with the Orson Hyde Memorial Garden and the Jewish settlement of Beit Orot, bordering on the Tzurim Valley and the Mitzpe Hamasu'ot ('Beacons Lookout') site, where the Temple Mount Sifting Project facilities are located.[33][34] What lays north of here belongs to Mount Scopus. On the south-eastern slope of the Mount of Olives lies the Palestinian Arab village of al-Eizariya, identified with the ancient village of Bethany mentioned in the New Testament; a short distance from the village centre, towards the top of the mount, is the traditional site of Bethphage, marked by a Franciscan church.[33]

The construction of the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, better known locally as the Mormon University, owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) near the Tzurim Valley which separates the Mount of Olives from Mount Scopus, initially sparked controversy because of concerns that the Mormons would engage in missionary activities. After the Mormons pledged not to proselytize in Israel, work on the building was allowed to proceed.[35]

Gallery

Augusta Victoria Hospital and its church

Augusta Victoria Hospital and its church

.JPG.webp) BYU Jerusalem Center (the "Mormon University")

BYU Jerusalem Center (the "Mormon University")

So-called "Tomb of Absalom"

So-called "Tomb of Absalom" So-called "Tomb of Zechariah"

So-called "Tomb of Zechariah"

See also

- Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery

- Beit Orot, Jewish settlement on the Mount of Olives

- Ma'ale ha-Zeitim, Jewish settlement on the Mount of Olives

- Olivet (disambiguation)

References

- Har-El, Menashe (1977). This is Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Canaan Publishing House. p. 117.

- Ussishkin, David (May 1970). "The Necropolis from the Time of the Kingdom of Judah at Silwan, Jerusalem". The Biblical Archaeologist. 33 (2): 33–46. doi:10.2307/3211026. JSTOR 3211026. S2CID 165984075.

- "International committee vows to restore Mount of Olives". Ynetnews. 8 November 2010.

- "The Ancient Olive Trees on the Mount of Olives". Ministry of Agriculture & Rural Development. Government of Israel. Archived from the original on 2019-04-28. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- Hull, Edward (1885). Mount Seir, Sinai and Western Palestine. Richard Bentley and Son, London. p. 152.

- Har-el, Menashe (1977). This is Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Canaan. pp. 120–23.

- Josephus, the Jewish War, 2.261-63; Antiquities of the Jews, 20.169-72

- Gray, Rebecca (1993). Prophetic figures in late Second Temple Jewish Palestine: the evidence from Josephus. New York, N.Y. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-19-507615-8.

- Nom de Deu, J. (1987). Relatos de Viajes y Epistolas de Peregrinos Jud.os a Jerusalén. Madrid. p. 82.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Menashe Har-El (April 2004). Golden Jerusalem. Gefen Publishing House Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 978-965-229-254-4.

- Sheleg, Yair (2007-04-07). "The good jailer". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- To Rule Jerusalem By Roger Friedland, Richard Hecht, 2000, p. 39, "Tourists entering East Jerusalem had to present baptismal certificates or other proof they were not Jewish."

- Thomas A Idinopulos, Jerusalem, 1994, p. 300, "So severe were the Jordanian restrictions against Jews gaining access to the old city that visitors wishing to cross over from west Jerusalem...had to produce a baptismal certificate."

- Armstrong, Karen, Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths, 1997, "Only clergy, diplomats, UN personnel, and a few privileged tourists were permitted to go from one side to the other. The Jordanians required most tourists to produce baptismal certificates—to prove they were not Jewish ... ."

- Ferrari, Silvio; Benzo, Andrea (2016-04-15). Between Cultural Diversity and Common Heritage: Legal and Religious Perspectives on the Sacred Places of the Mediterranean. Routledge. ISBN 9781317175025.

- Bronner, Ethan; Kershner, Isabel (2009-05-10). "Parks Fortify Israel's Claim to Jerusalem". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- Alon, Amos (1995). Jerusalem: Battlegrounds of Memory. New York: Kodansha Int'l. p. 75. ISBN 1-56836-099-1.

After 1967, it was discovered that tombstones had been removed from the ancient cemetery to pave the latrines of a nearby Jordanian army barrack.

- Meron Benvenisti (1996). City of Stone: The Hidden History of Jerusalem. University of California Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-520-91868-9.

- Har-El, Menashe. Golden Jerusalem, Gefen Publishing House Ltd, 2004, p. 126. ISBN 965-229-254-0. "The majority (50,000 of the 70,000) was desecrated by the Arabs during the nineteen years of Jordanian rule in eastern Jerusalem."

- Tessler, Mark A. A History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Indiana University Press, 1994. p. 329. ISBN 0-253-20873-4.

- Blum, Yehuda Zvi (1987). For Zion's Sake. Associated University Presse. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8453-4809-3.

- Mount of Olives security beefed up to stop vandalism, Jerusalem Post 17-12-2009

- Has Israel abandoned the Mount of Olives?, Jerusalem Post 15-05-2010

- Vandalism returns to Mount of Olives cemetery, Ynet News 12-05-2010

- Shameful dereliction at the Mt. of Olives Cemetery, Jerusalem Post 06-11-2010

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, book 9, chapter 10, paragraph 4, verse 225, William Whiston

- Daniel Wachs and Dov Levitte, Earthquake Risk and Slope Stability in Jerusalem, Environmental Geology and Water Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 183–86, 1984

- Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine, Vol. 1. p. 420, 1899; Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, April 1874, p. 102

- Mount of Olives description, from www.goisrael.com Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Matthew 21:1; 26:30, etc.

- Matthew 26:39

- G. R. S. Mead (1963). "2". Pistis Sophia. Jazzybee Verlag.

- Alternative Tourism Group (ATG)- Study Center. The Mount of Olives

- "Emek Tzurim". The City of David. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-02-12. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- "Jerusalem – Beyond the Old City Walls". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. July 22, 1946. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

External links

Media related to Mount of Olives at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mount of Olives at Wikimedia Commons- Mount of Olives website

- Har Hazeitim website

- Interactive Panoramas of the Mount of Olives – jerusalem360.com, GoJerusalem.com

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.