Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry VI (German: Heinrich VI.; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany (King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was also King of Sicily.

| Henry VI | |

|---|---|

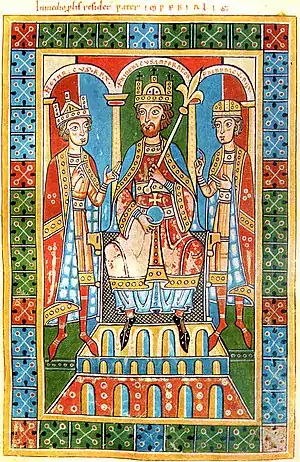

Contemporary portrait from the Liber ad honorem Augusti, 1196 | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 15 April 1191 – 28 September 1197 |

| Coronation | 15 April 1191, Rome |

| Predecessor | Frederick I Barbarossa |

| Successor | Otto IV |

| King of Germany (King of the Romans) | |

| Reign | 15 August 1169 – 28 September 1197 |

| Coronation | 15 August 1169, Aachen |

| Predecessor | Frederick I Barbarossa |

| Successor | Philip and Otto IV |

| King of Italy | |

| Reign | 21 January 1186 – 28 September 1197 |

| Coronation | 21 January 1186, Milan |

| Predecessor | Frederick I Barbarossa |

| Successor | Otto IV |

| King of Sicily | |

| Reign | 25 December 1194 – 28 September 1197 |

| Coronation | 25 December 1194, Palermo |

| Predecessor | William III |

| Successor | Constance (as sole monarch) |

| Co-ruler | Constance |

| Born | November 1165 Nimwegen, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 28 September 1197 (aged 31) Messina, Kingdom of Sicily |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor |

| House | Hohenstaufen |

| Father | Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy |

Henry was the second son of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy. Well educated in the Latin language, as well as Roman and canon law, Henry was also a patron of poets and a skilled poet himself. In 1186 he was married to Constance of Sicily, the posthumous daughter of the Norman king Roger II of Sicily. Henry, stuck in the Hohenstaufen conflict with the House of Welf until 1194, had to enforce the inheritance claims by his wife against her nephew Count Tancred of Lecce. Henry's attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Sicily failed at the siege of Naples in 1191 due to an epidemic, with Empress Constance captured. Based on an enormous ransom for the release and submission of King Richard I of England, he conquered Sicily in 1194; however, the intended unification with the Holy Roman Empire ultimately failed due to the opposition of the Papacy. In Sicily, Henry had a reputation for ruthless suppression of political opponents.[1] Until this day, he is sometimes given the nickname "the Cruel" (il crudele) by Italian historiography.[2][3]

Henry threatened to invade the Byzantine Empire after 1194 and succeeded in extracting a ransom, the Alamanikon, from Emperor Alexios III Angelos in return for cancelling the invasion. He made the Kingdom of Cyprus and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia formal subjects of the empire and compelled Tunis and Tripolitania to pay tribute to him. In 1195 and 1196, he attempted to turn the Holy Roman Empire from an elective to a hereditary monarchy, the so-called Erbreichsplan, but met strong resistance from the prince-electors. Henry pledged to go on crusade in 1195 and began preparations. A revolt in Sicily was crushed in 1197. The Crusaders set sail for the Holy Land that same year but Henry died of illness at Messina on 28 September 1197 before he could join them. His death plunged the Empire into the chaos of the German throne dispute for the next 17 years.

Biography

Early life

Henry was born in autumn 1165 at the Valkhof pfalz of Nijmegen to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy. At the age of four his father had him elected King of the Romans during a Hoftag in Bamberg at Pentecost 1169. Henry was crowned on 15 August at Aachen Cathedral.[4][5]

Henry accompanied his father on his Italian campaign of 1174–76 against the Lombard League, whereby he was educated by Godfrey of Viterbo and associated with minnesingers like Friedrich von Hausen, Bligger von Steinach and Bernger von Horheim. Henry was fluent in Latin and, according to the chronicler Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, was "distinguished by gifts of knowledge, wreathed in flowers of eloquence, and learned in canon and Roman law". He was a patron of poets and poetry, and he almost certainly composed the song Kaiser Heinrich, now among the Weingarten Song Manuscripts. According to his rank and with Imperial Eagle (Reichsadler), regalia, and a scroll, he is the first and foremost to be portrayed in the famous Codex Manesse, a 14th-century songbook manuscript featuring 140 reputed poets; at least three poems are attributed to a young and romantically minded Henry VI. In one of those he describes a romance that makes him forget all his earthly power, and neither riches nor royal dignity can outweigh his yearning for that lady (ê ich mich ir verzige, ich verzige mich ê der krône – before I give her up, I'd rather give up the crown).

Arms of the House of Hohenstaufen

Arms of the House of Hohenstaufen.svg.png.webp) Arms of the House of Hohenstaufen as Holy Roman Emperor

Arms of the House of Hohenstaufen as Holy Roman Emperor.svg.png.webp) Attributed coat of arms of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor (Codex Manesse)

Attributed coat of arms of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor (Codex Manesse)

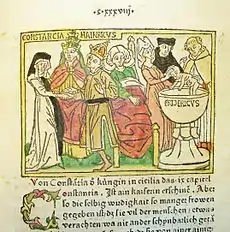

Emperor's son

Having returned to Germany in 1178, Henry supported his father against insurgent duke Henry the Lion. He and his younger brother Frederick received the knightly accolade at the Diet of Pentecost Mainz in 1184.[6] The emperor had already entered into negotiations with King William II of Sicily to betroth his son and heir with William's aunt Constance by 1184. Constance, almost 30 years old at that time, was said to have been confined in Santissimo Salvatore, Palermo as a nun since childhood to keep celibacy due to a prediction that "her marriage would destroy Sicily" despite having become the sole legitimate heir to William as the marriage of the latter had remained childless; and, after the latter's death in November 1189, Henry had the opportunity of adding the Sicilian crown to the imperial one. He and Constance were married on 27 January 1186 in Milan.[7]

In the Hohenstaufen conflict with Pope Urban III, Henry moved to the March of Tuscany, and with the aid of his deputy Markward von Annweiler devastated the adjacent territory of the Papal States. Back in Germany, he became sovereign ruler of the Empire, as his father had died while on the Third Crusade in 1190. Henry tried to secure his rule in the Low Countries by elevating Count Baldwin V of Hainaut to a margrave of Namur, and at the same time he tried to reach a settlement with rivalling Duke Henry of Brabant. Further difficulties arose when the exiled Welf duke Henry the Lion returned from England and began to subdue large estates in his former Duchy of Saxony. A Hohenstaufen campaign to Saxony had to be abandoned when King Henry received the message of the death of King William II of Sicily on 18 November 1189. The Sicilian vice-chancellor Matthew of Ajello pursued the succession of Count Tancred of Lecce and gained the support of the Roman Curia.

To assert his own rights in the inheritance dispute, Henry initially supported Tancred's rival Count Roger of Andria and made arrangements for a campaign to Italy. The next year he concluded a peace agreement with Henry the Lion at Fulda and moved farther southwards to Augsburg, where he learned that his father had died on crusade attempting to cross the Saleph River near Seleucia in the Kingdom of Cilicia (now part of Turkey) on 10 June 1190.[8]

Imperial coronation

While he sent an Imperial army to Italy, Henry initially stayed in Germany to settle the succession of Louis III, Landgrave of Thuringia, who had also died on the Third Crusade. He had planned to seize the Thuringian landgraviate as a reverted fief, but Louis' brother Hermann was able to reach his enfeoffment. The next year, the king followed his army across the Alps. In Lodi he negotiated with Eleanor of Aquitaine, widow of King Henry II of England, to break the engagement of her son King Richard with Alys, a daughter of late King Louis VII of France. He hoped to deteriorate English-French relations and to isolate Richard, who had offended him by backing Count Tancred in Sicily. Eleanor acted cleverly; she reached Henry's assurance that he would not interfere in her son's conflict with King Philip II of France, and she would also prevent the marriage of Henry's younger brother Conrad with Berengaria of Castile to confine the Hohenstaufen claims to power.

Henry entered into further negotiations with the Lombard League cities and with Pope Celestine III on his Imperial coronation, and ceded Tusculum to the Pope. At Easter Monday on 15 April 1191, in Rome, Henry and his consort Constance were crowned Emperor and Empress by Celestine. The crown of Sicily, however, was harder to gain, as the Sicilian nobility had chosen Count Tancred of Lecce as their king. Henry began his work campaigning in Apulia and besieging Naples, but he encountered resistance when Tancred's vassal Margaritus of Brindisi came to the city's defence, harassed Henry's Pisan navy, and nearly destroyed the later arriving Genoese contingent. Moreover, the Imperial army had been heavily hit by an epidemic, and Henry ultimately had to abandon the siege. Upon his retreat, those cities that had surrendered to Henry resubmitted to Tancred. As a result, Constance, who was left in the palace of Salerno as a sign that Henry would soon return, was betrayed and handed over to Tancred.[8]

Henry had to return to Germany when he learned that Henry the Lion had again incited a conflict with the Saxon House of Ascania and the Counts of Schauenburg. His son Henry of Brunswick deserted from the Imperial army in Italy and was ostracized by the emperor at the Hoftag in Worms at Pentecost 1192. However, Henry VI had to realise that his powers were limited: after his closest ally in Saxony, Archbishop Wichmann of Magdeburg died, he concluded another armistice with inflammatory Henry the Lion.

Meanwhile, despite the fact that his wife had been captured by Sicilians, Henry refused Celestine III's offers to make peace with Tancred. While Tancred would not permit Constance to be ransomed unless Henry recognized him, Henry complained of her capture to Celestine. In June 1192 Constance was released on the intervention of Pope Celestine III, who in return recognized Tancred as King of Sicily. Constance was to be sent to Rome for Celestine III to put pressure on Henry, but German soldiers managed to set up an ambush on the border of Papal States and freed Constance.

On the other hand, the emperor was able to strengthen his power base in the Duchy of Swabia, when he inherited the possessions of Henry the Lion's cousin Welf VI. During the election of a new Bishop of Lüttich in September 1191, he favored Albert de Rethel for Albert was a maternal-uncle of Empress Constance, whom both he and Constance had planned to be the next bishop of Liege, but at the time of election Empress Constance had been imprisoned by Sicilians, and the other candidate Albert of Louvain the brother of Duke Henry of Brabant gained more support. In January 1192 Henry claimed the election was under dispute and appointed his newly made imperial chancellor Lothar of Hochstaden, provost of the church of St Cassius in Bonn and brother of Count Dietrich of Hochstaden instead, and in September 1192 he proceeded to Lüttich (Liège) to enforce the succession. The majority of the electors of Liège accepted the imperial decision because of the emperor's threat, and Albert de Rethel also relinquished and indignantly refused a financial settlement offered by the emperor. Albert of Louvain had to yield and sought support from the pope in Rome and from the Archbishop of Reims. In Reims, he took the holy orders with papal consent, but he was killed soon after by hired assassins. His brother Duke Henry chose to conclude a peace agreement with the emperor but remained a bitter enemy.

Emperor Henry already was concerned with the deposition of the Welf supporter Archbishop Hartwig II of Bremen. He further had to arbitrate in a conflict in the Margraviate of Meissen on the eastern border of the Empire, where the Wettin margrave Albert I had to fend off the claims raised by his brother Theoderic and Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia. Meanwhile, the opposition in the west took on a dramatic scale, when the dukes of Brabant and Limburg joined forces with Archbishop Bruno III of Cologne. A massive confederacy against the emperor loomed ahead, including Archbishop Conrad of Mainz, Archchancellor of Germany, and Duke Ottokar I of Bohemia, as well Henry's old rival Henry the Lion, the Swabian House of Zähringen, the English Crown, and the pope, irritated by the killing of Albert of Louvain.[8]

Capture of Richard the Lionheart

At this stage, Henry had a stroke of good fortune when the Babenberg duke Leopold V of Austria gave him his prominent prisoner, Richard the Lionheart, King of England, whom he had captured on his way back from the Third Crusade and held at Dürnstein Castle. On 28 March 1193, Richard was handed over to the emperor in Speyer and imprisoned at Trifels Castle, taking revenge for Richard's alliance with Tancred of Lecce. Ignoring his near excommunication by Pope Celestine III for imprisoning a former crusader, he held the English King for a ransom of 150,000 silver marks and officially declared a dowry of Richard's niece Eleanor, who was to marry Duke Leopold's son Frederick. The opposition princes had to face the defeat of their mighty ally and to refrain from their plans to overthrow the Hohenstaufen dynasty.[11]

Backed by his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine, who successfully defended his interests against his rival brother John, Count of Mortain and his ally King Philip of France, King Richard procured his release in exchange for the huge ransom, a further interest payment, and his oath of allegiance to Henry. In turn the emperor under threat of military violence demanded the restitution of the French lands, which John had seized upon approval by Philip during Richard's absence. Henry not only gained another vassal and ally, he could also assume the role of a mediator between England and France. He and Richard ceremoniously reconciled at the Hoftag in Speyer during Holy Week 1194: the English king publicly regretted any hostilities, genuflected, and cast himself on the emperor's mercy. He was released and returned to England.[12]

At the same time, Henry settled the longstanding conflict with the Welf dynasty when he secured the marriage of Agnes of Hohenstaufen, daughter of his half-uncle Count Palatine Conrad, to Henry the Lion's son Henry of Brunswick, followed by a peace agreement in March 1194.

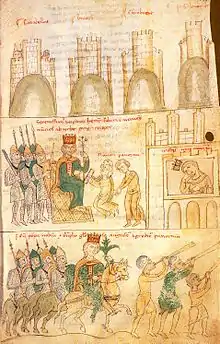

Conquest of Sicily

.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, the situation in Southern Italy had grown worse: After Henry's defeat at Naples, Tancred's brother-in-law Count Richard of Acerra had reconquered large parts of Apulia, and Tancred himself had reached the allowance of his claims by the pope. Henry was granted free passage in Northern Italy, having forged an alliance with the Lombard communes. In February 1194, Tancred of Lecce died, leaving as heir a young boy, William III, under the tutelage of his mother Sibylla of Acerra. In May Emperor Henry, based on King Richard's ransom, again set out for Italy. He reached Milan at Pentecost and occupied Naples in August. He met little resistance and on 20 November 1194 entered Palermo capital of Kingdom of Sicily and was crowned king on 25 December. On the next day his wife Constance, who had stayed back in Iesi, gave birth to his only son and heir Frederick II, the future emperor and king of Sicily and Jerusalem.[8]

The young William and his mother Sibylla had fled to Caltabellotta Castle; he officially renounced the Sicilian kingdom in turn for the County of Lecce and the Principality of Capua. A few days after Henry's coronation, however, the royal family and several Norman nobles were accused of a coup attempt and arrested. Henry is said to have had William blinded and castrated, while many of his liensmen were burned alive. Some, however, like the Siculo-Greek Eugene of Palermo, transitioned into the new Hohenstaufen government with ease. William probably was deported to Altems (Hohenems) Castle in Swabia, where he died in captivity about 1198.

In March 1195 Henry held a Hoftag in Bari and appointed his wife Constance Sicilian queen regnant, though with Henry's liensman Conrad of Urslingen, elevated to a hereditary duke of Spoleto, as Imperial vicar to secure the emperor's position in Southern Italy. He placed further ministeriales in the Sicilian administration, like the Troia bishop Walter of Palearia who became chancellor. His loyal henchman Markward von Annweiler was appointed a duke of Ravenna, placing him in a highly strategic position to control the route to Sicily via the Italian Romagna region and the Apennines. Henry's younger brother Philip of Swabia was vested with the large estates of late margravine Matilda in Tuscany. The emperor also felt strong enough to send home the Pisan and Genoese ships without giving their governments the promised concessions.[13]

Universal ruler

The Sicilian kingdom added to Henry's personal and Imperial revenues an income without parallel in Europe. However, his aims to integrate Sicily into the Empire as a second power base of the Hohenstaufen dynasty were not realised during his lifetime. The negotiations with Pope Celestine III to approve the unification (unio regni ad imperium) in return of another crusade reached a deadlock. On the other hand, his beliefs of a universal rule according to the translatio imperii concept collided with the existence of the Byzantine Empire, reflected in Henry's expansionist policies by the imposition of suzerainty over King Leo I of Armenia and King Aimery of Cyprus.

In 1195 Henry's envoys in Constantinople raised claims to former Italo-Norman possessions around Dyrrachium (Durrës), one of the most important naval bases on the eastern Adriatic coast, and pressed for a contribution to the planned crusade. Upon the deposition of Emperor Isaac II Angelos Henry openly threatened with an attack on Byzantine territory. He already evolved plans to betroth his younger brother Philip to Isaac's daughter Princess Irene Angelina—deliberately or not—opening up a perspective to unite the Western and Eastern Empire under Hohenstaufen rule. According to the contemporary historian Niketas Choniates his legates were able to collect a large tribute from Isaac's brother and successor Alexios III, which, however, was not paid before Henry's death.[14]

When an armistice between Pisa and the Republic of Venice ended, the Pisans attacked Venetian ships in Marmora and carried out raids against theỉr premises in Constantinople. The matters escalated and the two sides went to war. The Byzantine emperor Alexios III Angelos was thought to be behind Pisan attacks. In 1197, Henry imposed a truce on them.[15][16] Previously, Pisa and Genoa had supported Henry's invasion of Italy while Venice chose to be neutral. But Henry granted Venice various rights in 1195 and 1197 while prevaricating over the more extensive privileges Pisa and Genoa claimed.[17][18][19] Henry's planned expansion against Thessaloniki and Constantinople, if it had happened, would have isolated Venice in its own gulf, and Venice was worrying that Alexios would rather submit to Henry than settle disgreements with Venice. Henry's death relieved both Venice and Constantinople of their worries. On the news of Henry's death, the Byzantine "German tax" was abolished.[20][21]

When Henry died, he was the most powerful monarch in Christendom, being Holy Roman Emperor, King of Germany, Burgundy, Italy, Sicily, feudal overlord of the Kings of England, Lesser Armenia and Cyprus, and tributary lord of Northern African princes.[22]

Hereditary monarchy

.jpg.webp)

In summer 1195 Henry returned to Germany, in order to call for support to launch his crusade and to arrange his succession in the case of his death. However, he first again had to deal with the quarrels in the Wettin Margraviate of Meissen upon the death of Margrave Albert I. As Albert had tried to gain control over the adjacent Pleissnerland, an Imperial Hohenstaufen territory, Henry took the occasion to deny the inheritance claims of the margrave's younger brother Theodoric and seized the Meissen territory for himself. In October he reconciled with Archbishop Hartwig of Bremen at Gelnhausen and was able to obtain the support of numerous Saxon and Thuringian nobles for his crusade which was scheduled to begin on Christmas 1196.

His next aim was to make the imperial crown hereditary. Henry tried to secure the Imperial election of his son Frederick II as King of the Romans, which however met with objections raised by Archbishop Adolf of Cologne. Spending the winter in Hagenau Castle, the emperor and his ministeriales evolved the idea of a hereditary monarchy. Though they would have lost their right to elect the kings, the secular princes themselves wished to make their Imperial fiefs hereditary and to be inheritable by the female line as well, and Henry agreed to consider these demands. The emperor also bought the support of ecclesiastical princes by announcing that he would be willing to give up the Jus Spolii and the right to receive recurring earnings from church lands during a period of sede vacante. At the Diet of Würzburg, held in March/April 1196, he managed to convince the majority of the princes to vote for his proposal. However, Archbishop Adolf of Cologne did not even put in an appearance and several princes, predominantly in Saxony and Thuringia, were still dissatisfied.[23]

While in July 1196 Henry proceeded to Burgundy and Italy in order to negotiate with Pope Celestine III, the resistance in Germany grew. At the following diet at Erfurt in October, a majority of the princes rejected the emperor's plans. Furthermore, the Pope, still concerned in view of the Hohenstaufen rule over Sicily, broke off the talks. Nevertheless, on Christmas Henry's son Frederick II was elected King of the Romans in Frankfurt.

Death

At the same time, the emperor stayed in Capua, where he had Count Richard of Acerra, held in custody by his ministerialis Dipold von Schweinspeunt, cruelly executed. He entered Sicily in March 1197 and applied himself to prepare his crusade in Messina.

Soon after, the transition to Hohenstaufen's rule in Italy spurred revolts, especially around Catania and southern Sicily, which his German soldiers led by Markward of Annweiler and Henry of Kalden suppressed mercilessly. The rebels even sought to make Count Jordan of Bovino king in Henry's place. Some contemporary Germans (who were hostile to Empress Constance) even accused her of directly collaborating with the rebels, even though recent research like the work of Theo Kölzer shows that this was unlikely. Kölzer opines though that Henry's "discipline methods" in Sicily had put a dent on the relationship between wife and husband, and it was possible that Constance passively tolerated the rebels.[24] In the midst of preparations Henry fell ill with chills while hunting near Fiumedinisi and on 28 September died, likely of malaria (contracted since the siege of Napoli in 1191 and had never completely healed), in Messina,[25] although some immediately accused Constance of poisoning him.[26] His wife Constance had him buried at Messina; in 1198, his mortal remains were transferred to Palermo Cathedral. Various items were removed from Henry VI's grave in the late eighteenth century, some of which are now in the British Museum in London. They include the remains of a shoe, a head band and an ornate silk textile that originally wrapped the body.[27]

Henry's minor son Frederick II was to inherit both the Kingdom of Sicily and the Imperial crown. However, a number of princes around Archbishop Adolf of Cologne elected the Welf Otto of Brunswick, son of Henry the Lion, anti-king. To defend the claims of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, Frederick's uncle Philip of Swabia had himself elected King of the Romans in March 1198. The German throne quarrel lasted nearly twenty years, until Frederick was again elected king in 1212 and Otto, defeated by the French in the 1214 Battle of Bouvines and abandoned by his former allies, finally died in 1218.[8]

Reception

During his rule in Germany, Henry moved from one Kaiserpfalz residence to another or—to a lesser extent—stayed at Prince-bishop's sees in the tradition of the medieval itinerant kingship. He concentrated on the Franconian core locations of his kingdom, while the Bavarian and Saxon lands were less subject to the central authority. His travel routes through Germany as well as his campaigns in Italy are documented by numerous deeds he issued year by year.

The emperor strongly relied on high-ranking clergy like the archbishops Philip of Cologne and Conrad of Mainz. Several contemporary accounts of his life given by ecclesiastical chroniclers like Godfrey of Viterbo or Peter of Eboli in his Liber ad honorem Augusti (on the emperor's conquest of Sicily) paint a bright picture of Henry's rule; while the annals by Otto of Sankt Blasien are considered more objective. In his Arnoldi Chronica Slavorum the chronicler Arnold of Lübeck concentrates on the dispute between the Hohenstaufen and Welf dynasties from a pronounced Welf perspective, while Gislebert of Mons tells of Henry's policies in Hainaut and Flanders. The Hohenstaufen rule in Italy and the Mezzogiorno is documented by the chronicles of Archbishop Romuald of Salerno and Richard of San Germano. Henry's conflict with King Richard I of England is rendered by Roger of Hoveden and Gervase of Tilbury, expressing their negative attitudes towards the emperor.

While being overshadowed by the legendary figures of his father and son, the two Fredericks, Henry is generally considered to be a talented leader and his reign is also considered to be remarkable. Koenigsberger calls him an "immensely able politician", who was able to break the alliance of Western kings, who combined their forces against his great power. But the empire, depending much on the person of the ruler, like other medieaval empires, collapsed when he died.[28][29]

Later historians stressed the fact of Henry's early death and the succeeding throne quarrel as a stroke of fate and a major setback for the development of a German nation state begun under his father Frederick Barbarossa. On the other hand, the emperor's stern measures in Sicily earned him the reputation of a cruel and merciless ruler. Present-day historical research classifies Henry as a man of his time; though a capable ruler he had to cope with the centrifugal forces while at the same time he overstretched the Hohenstaufen realm to an extent that finally could not be kept together.

Notes

- Pavlac, Brian (18 October 2013). "Henry VI". In Emmerson, Richard K. (ed.). Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-136-77519-2.

- Bausilio, Giovanni (19 January 2018). Re e regine di Napoli (in Italian). Key Editore. p. 51. ISBN 978-88-6959-944-6. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- Ambra, Sebastiano (18 November 2022). Breve storia di Catania (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. p. 79. ISBN 978-88-227-7091-2. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- Peter H. Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire, (Harvard University Press, 2016), p. 307.

- John B. Freed, Frederick Barbarossa: The Prince and the Myth, (Yale University Press, 2016), p. 351.

- Godfrey of Viterbo: Historical Writing and Imperial Legitimacy at the Early Hohenstaufen Court, Kai Hering, Godfrey of Viterbo and His Readers: Imperial Tradition and Universal History in Late Medieval Europe, ed. Thomas Foerster, (Ashgate Publishing, 2015), p. 59.

- The Marriage of Henry VI and Constance of Sicily: Prelude and Consequences, Walter Frohlich, Anglo~Norman Studies: XV. Proceedings of the Battle Conference, ed. Marjorie Chibnall, (The Boydell Press, 1993), p. 109.

- Horst Fuhrmann (1986). Germany in the High Middle Ages: c. 1050–1200. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-521-31980-5.

- Bojcov, Michail A. (2005). Wie Der Kaiser Seine Krone Aus Den Füssen Des Papstes Empfing. pp. 163–198. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Huijbers, Anne (23 May 2023). "Le couronnement impérial de Sigismond de Luxembourg à Rome (1433) : entre rite papal et perception humaniste". Sacres et couronnements en Europe : Rite, politique et société, du Moyen Âge à nos jours (in French). Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 207–220. ISBN 978-2-7535-9414-2. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "On this day in history – Richard the Lionheart was captured by Leopold V of Austria". History Scotland. 20 December 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Toby Purser (2004). Medieval England, 1042–1228. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32760-6.

- Donald Matthew (1992). The Norman Kingdom of Sicily - p. 290. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26911-7.

- Charles M. Brand (1968). Byzantium confronts the West, 1180–1204. History Scotland. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Nicol, Donald M. (7 May 1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-521-42894-1. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Madden, Thomas F. (29 September 2006). Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice. JHU Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8018-9184-7. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Madden, Thomas F. (29 September 2006). Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice. JHU Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-8018-9184-7. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- McKitterick, Rosamond; Abulafia, David (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, C.1198-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-521-36289-4. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Abulafia, David (24 November 2005). The Two Italies: Economic Relations Between the Norman Kingdom of Sicily and the Northern Communes. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-02306-1. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Ivetic, Egidio (27 May 2022). History of the Adriatic: A Sea and Its Civilization. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-5095-5253-5. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Nicol 1992, p. 118.

- Schimmelpfennig, Bernhard (1 January 2011). Könige und Fürsten, Kaiser und Papst im 12. Jahrhundert (in German). Oldenbourg Verlag. p. 57. ISBN 978-3-486-70255-2. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Alfred Haverkamp. "Hochmittelalter" (PDF). UPI. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Kölzer, Theo (2006). "Kaiserin Konstanze, Gemahlin Heinrichs VI.". In Fössel, Amalie (ed.). Frauen der Staufer (in German). Gesellschaft für staufische Geschichte e.V. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-3-929776-16-4. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- In 1197, although "the well-prepared crusade of Emperor Henry VI aimed at winning the Holy Land, it also aimed at attaining the ancient goal of Norm[an] policy in the E[ast]: the conquest of the Byz[antine] Empire." See Werner Hilgemann and Hermann Kinder, The Anchor Atlas of World History, Volume I: From the Stone Age to the Eve of the French Revolution, trans. Ernest A. Menze (New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1974), 153; "Henry pressed territorial and political claims against Constantinople, demanding territories the Normans had held in 1185 and using a remote family connection to pose as the avenger of the deposed emperor Isaac II. … even Pope Innocent III was frightened by the German emperor's claims of world domination. As events turned out, however, Henry died suddenly in 1197 before he could carry out his plans for eastward expansion." See Timothy E. Gregory, A History of Byzantium (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 273.

- Schneidmüller, Bernd; Weinfurter, Stefan (2003). Die deutschen Herrscher des Mittelalters: historische Portraits von Heinrich I. bis Maximilian I. (919-1519) (in German). C.H.Beck. p. 269. ISBN 978-3-406-50958-2. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- British Museum Collection

- Pavlac 2013, p. 323.

- Koenigsberger, H. G. (14 January 2014). Medieval Europe 400 - 1500. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-317-87089-0. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

Sources

- Alberic of Troisfontaines, Chronicon

- David Abulafia, Frederick II