Henry Wheaton

Henry Wheaton (November 27, 1785 – March 11, 1848) was a United States lawyer, jurist and diplomat.[1][2] He was the third reporter of decisions for the United States Supreme Court, the first U.S. minister to Denmark, and the second U.S. minister to Prussia.

Henry Wheaton | |

|---|---|

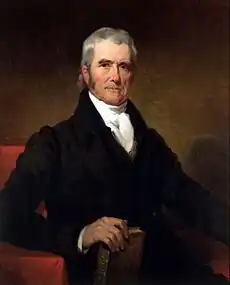

Portrait of Henry Wheaton by George Peter Alexander Healy, ca. 1847 | |

| 2nd United States Minister to Prussia | |

| In office September 29, 1837 – July 18, 1846 Chargé d'affaires: June 9, 1835 to September 29, 1837 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson Martin Van Buren William Henry Harrison John Tyler James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | John Quincy Adams (1797) |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Jackson Donelson |

| 1st United States Minister to Denmark | |

| In office September 20, 1827 – May 29, 1835 | |

| President | John Quincy Adams Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Diplomatic relations established |

| Succeeded by | Jonathan F. Woodside |

| 3rd Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office 1816–1827 | |

| Preceded by | William Cranch |

| Succeeded by | Richard Peters |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henry Wheaton November 27, 1785 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | March 11, 1848 (aged 62) Dorchester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Brown University |

| Signature | |

Biography

He was born at Providence, Rhode Island. He graduated from Brown University (then called Rhode Island College) in 1802, was admitted to the bar in 1805, and, after two years' study abroad in Poitiers and London,[3][4] practiced law at Providence (1807-1812) and at New York City (1812-1827).[5] From 1812 to 1815, he edited National Advocate, the organ of the administration party. There he published notable articles on the question of neutral rights in connection with the then-existing war with England. On 26 October 1814, he became division judge advocate of the army.[3] He was a justice of the Marine Court of New York City from 1815 to 1819.[5]

From 1816 to 1827, he edited reports of the Supreme Court, as the third Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States. Aided by Justice Joseph Story, his reports were known for their comprehensive notes and summaries of the arguments presented by each side. However, the volumes were slow in appearing and costly. Wheaton's successor Richard Peters condensed his work, and Wheaton sued him, claiming infringement of his common-law copyright. The Supreme Court rejected his claim in Wheaton v. Peters in 1834, which was the Court's first copyright case.

He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1820.[6] He was elected a member of the convention to form a new constitution for New York in 1821, was a member of the New York State Assembly (New York Co.) in 1824, and in 1825 was associated with John Duer and Benjamin F. Butler in a commission to revise the statute law of New York. He also took part in important cases, and was the sole associate of Daniel Webster in that which settled the limits of the state and federal legislation in reference to bankruptcy and insolvency.[3] In 1825, he aided in the revision of the laws of New York.[5]

His diplomatic career began in 1827, with an appointment to Denmark as chargé d'affaires.[5] He served until 1835, displaying skill in the settlement of the sound dues that were imposed by Denmark on the vessels of all countries, and obtained modifications of the quarantine regulations. He was noted for his research into the Scandinavian language and literature, and was elected a member of Scandinavian and Icelandic societies.[3] In 1829, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[7]

In 1835 he was appointed minister to Prussia, being promoted to minister plenipotentiary in 1837. He soon received full power to conclude a treaty with the Zollverein, which he pursued for the next six years. On 25 March 1844, he signed a treaty with Germany, for which he received high commendation from President Tyler and John C. Calhoun, the secretary of state. This was rejected by the U.S. Senate but served as the basis for subsequent treaties. He was made a corresponding member of the French Institute in 1843, and a member of the Royal Academy of Berlin in 1846.[3]

Other issues Wheaton dealt with during his diplomatic career were Scheldt dues, the tolls on the Elbe, and the rights of naturalized citizens.[4] In 1846 Wheaton was requested to resign as Prussian minister by the new president, Polk, who needed his place for another appointment. The request provoked general condemnation, but Wheaton resigned and returned to the United States.[5]

He was called at once to Harvard Law School as lecturer on international law, but illness prevented his acceptance.[3] He died at Dorchester, Massachusetts, on 11 March 1848.

Philosophy

Wheaton's general theory is that international law consists of "those rules of conduct which reason deduces, as consonant to justice, from the nature of the society existing among independent nations, with such definitions and modifications as may be established by general consent."[5]

Family connections

Wheaton's niece, Ellen Smith Tupper, became a noted beekeeper. Ellen Tupper's daughters included Unitarian Universalist ministers Eliza Tupper Wilkes and Mila Tupper Maynard, and educator Kate Tupper Galpin. Her grandson was artist Allen Tupper True.

Works

- Digest of the Law of Maritime Captures (1815)

- Supreme Court Reports (12 vols., New York, 1826–27)

- A Digest of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States from Its Establishment in 1789 to 1820 (1820–29)

- Life of William Pinkney, which he also abridged for publication in Sparks's "American Biography" series (1826)

- History of the Northmen, or Danes and Normans, from the Earliest Times to the Conquest of England by William of Normandy London: J. Murray, 1831 at Internet Archive, which Washington Irving said "evinced throughout the enthusiasm of an antiquarian, the liberality of a scholar, and the enlightened toleration of a citizen of the world" (French translation by Paul Guillot, Paris, 1844)

- Elements of International Law (1836).[8] This is his most important work, of which a 6th edition with the last corrections of the author and a memoir was prepared by William Beach Lawrence (Boston, 1855) and an 8th by Richard Henry Dana Jr. (Boston, 1866). The contents of the 8th edition were the source of controversy between Lawrence (who claimed his notes from earlier editions had been improperly copied) and Dana.

- History of Scandinavia, with Andrew Crichton (1838) A sequel to History of the Northmen.[4][9][10]

- Histoire du progrès des gens en Europe depuis la paix de Westphalie jusqu'au congres de Vienne, avec un précis historique du droit des gens européens avant la paix de Westphalie, written in 1838 for a prize offered by the French Academy of Moral and Political Science,[11] and translated in 1845 by W. B. Lawrence as A History of the Law of Nations in Europe and America, New York: Gould, Banks & Co.. The History took rank at once as one of the leading works on the subject of which it treats.[5][12]

- An Enquiry into the Validity of the British Claim to a Right of Visitation and Search of American Vessels suspected to be engaged in the Slave Trade (Philadelphia and London, 1842; 2d ed., 1858)

Wheaton translated the Code of Napoleon, but the manuscript was destroyed by fire. He also contributed numerous political, historical, and literary articles to the North American Review and other periodicals.

Notes

- Hicks, Frederick C. (1936). "Wheaton, Henry". In Malone, Dumas (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 20 (Werden-Zunser). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 39–42. Retrieved April 19, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Gilman, Daniel Coit; Peck, Harry Thurston; Colby, Frank Moore, eds. (1904). "WHEATON, Henry". The New International Encyclopaedia. Vol. XVII (TYP-ZYR). New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 679. hdl:2027/mdp.39015053671221. Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1889). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wheaton, Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 583.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- Wheaton, Henry (1836). Elements of International Law; with a Sketch of the History of the Science. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard – via Gallica.

- Andrew Crichton; Henry Wheaton (1841). Scandinavia, ancient and modern. Vol. 1. Harper and Brothers.

- Andrew Crichton; Henry Wheaton (1841). Scandinavia, ancient and modern. Vol. 2. Harper and Brothers.

- Wheaton, Henry (1841). Histoire des progrès du droit des gens en Europe depuis la Paix de Westphalie jusqu'au Congrès de Vienne, avec un précis historique du droit de gens européen avant la paix de Westphalie. Leipzig: Brockhaus. Retrieved April 20, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Wheaton, Henry (1845). History of the Law of Nations in Europe and America from the Earliest Times to the Treaty of Washington, 1842. New York: Gould, Banks & Co. Retrieved November 27, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

References

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Elizabeth Feaster Baker, Henry Wheaton, 1785-1848 (1937)