Heo Hwang-ok

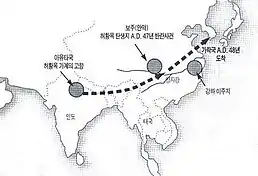

Heo Hwang-ok,[2] is a legendary queen mentioned in Samguk yusa, a 13th-century Korean chronicle. According to Samguk Yusa, she became the wife of King Suro of Geumgwan Gaya at the age of 16, after having arrived by boat from a distant kingdom called "Ayuta".[3] More than six million present day Koreans, especially from Gimhae Kim, Gimhae Heo and Incheon Yi clans, trace their lineage to the legendary queen as the direct descendants of her 12 children with King Suro.[4][5][6] Her native kingdom is believed to be located in India.[7][8] There is a tomb in Gimhae, South Korea, that is believed to be hers,[9] and a memorial in Ayodhya, India built in 2020.[10]

| Heo Hwang-ok | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empress Heo | |||||

A modern take on Heo Hwang-ok's visage. | |||||

| Queen consort of Geumgwan Gaya | |||||

| Tenure | 189 AD | ||||

| Predecessor | Princess Mother Jeonggyeon | ||||

| Successor | Lady Mojeong | ||||

| Born | 32 AD State of Ayuta | ||||

| Died | 189 AD (aged about 157) (1st day, 3rd months in Lunar) Gimhae, Gyeongsangnam-do | ||||

| Spouse | King Suro of Gaya | ||||

| Issue | King Geodeung of Gaya 10 other sons Lady Kim of Garak State[1] | ||||

| |||||

| Korean | 허황옥 許黃玉 | ||||

Origins

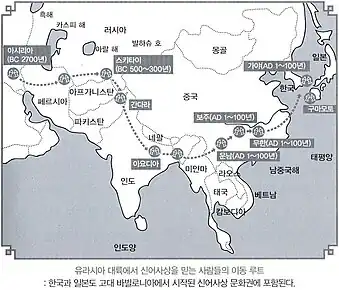

The legend of Heo is found in Garakguk-gi (the Record of Garak Kingdom) which is currently lost, but referenced within the Samguk Yusa.[11] According to the legend, Heo was a princess of the "Ayuta Kingdom". The extant records do not identify Ayuta except as a distant country. Written sources and popular culture often associate Ayuta with India but there are no records of the legend in India itself.[6] Byung-mo Kim, a professor and anthropologist at Hanyang University, linked Ayuta with Ayodhya in India based on phonetic similarity.[12] Grafton K. Mintz and Tae-hung Ha said it was an interesting note that Ayuta was the Ayutthaya Kingdom of Thailand, also due to phonetic similarities, "It is interesting to note that the city of Aythia was at one time the capital of the Kingdom of Thailand." but that they still backed an Indian origin by translating it as, "I am Princess of Ayuta (in India)".[13] However, according to George Cœdès, the kingdom of Ayutthaya was not founded until the year 1350, which was after the publication of Samguk Yusa.[13][14] Others theorize that the Ayuta Kingdom (Hangul: 아유타국, Hanja: 阿踰陁國) is a misinterpretation of the Ay Kingdom, a vassal to the Pandyan Empire of ancient Tamilakam as some sources allude to her coming from the southern part of India,[15] but a consensus is yet to be reached. Despite numerous theories and claims, Queen Heo's true origin is yet to be discovered.

Contrary to popular belief in India, the name, "Suriratna" (an Indian name usually assigned to the queen) does not appear in the Samguk Yusa and is in fact from a comic book called "Sri Ratna Kim Suro - The Legend of an Indian Princess in Korea" (2015) by Indian author Prasannan Parthasarathi. The name is based on the author's educated guess on the name "Hwang-ok" meaning Yellow Jade, making it "Suriratna", meaning Precious Stone in Hindi. In reality, there is no historical evidence that backs this claim as the name, "Suriratna", does not allude to a South Indian origin revolving around Tamil. Regardless of its authenticity, the name was popularized in several news articles within Korea and India despite its contemporary origins and lack of mention in Samguk Yusa.[16][17]

Marriage to Suro

After their marriage, Heo told King Suro that she was 16 years old.[18][19] She stated her given name as "Hwang-ok" ("Yellow Jade", 황옥, 黃玉) and her family name as "Heo" (허, or "Hurh" 許). She described how she came to Gaya as follows: the Heavenly Lord (Sange Je) appeared in her parents' dreams. He told them to send Heo to Suro, who had been chosen as the king of Gaya. The dream showed that the king had not yet found a queen. Heo's father then told her to go to Suro. After two months of a sea journey, she found Beondo, a peach which fruited only every 3.000 years.[5]

According to the legend, the courtiers of King Suro had requested him to select a wife from among the maidens they would bring to the court. However, Suro stated that his selection of a wife will be commanded by the Heavens. He commanded Yuch'ŏn-gan to take a horse and a boat to Mangsan-do, an island to the south of the capital. At Mangsan, Yuch'ŏn saw a vessel with a red sail and a red flag. He sailed to the vessel, and escorted it to the shores of Kaya (or Gaya, present-day Gimhae). Another officer, Sin'gwigan went to the palace, and informed the King of the vessel's arrival. The King sent nine clan chiefs, asking them to escort the ship's passengers to the royal palace.[20]

Princess Heo stated that she wouldn't accompany the strangers. Accordingly, the King ordered a tent to be pitched on the slopes of a hill near the palace. The princess then arrived at the tent with her courtiers and slaves. The courtiers included Sin Po (or Sin Bo, 신보, 申輔) and Cho Kuang (or Jo Gwang, 조광, 趙匡). Their wives were Mojong (모정, 慕貞) and Moryang (모량, 慕良) respectively. The twenty slaves carried gold, silver, jewels, silk brocade, and tableware and gems.[21] Before marrying the king, the princess took off her silk trousers (mentioned as a skirt in a different section of Samguk Yusa) and offered them to the mountain spirit. King Suro tells her that he also knew about Heo's arrival in advance, and therefore, did not marry the maidens recommended by his courtiers.[5]

When some of the Queen's escorts decided to return home, King Suro gave each of them thirty rolls of hempen cloth (one roll was of 40 yards). He also gave each person ten bags of rice for the return voyage. A part of the Queen's original convoy, including the two courtiers and their wives, stayed back with her. The queen was given a residence in the inner palace, while the two courtiers and their wives were given separate residences. The rest of her convoy were given a guest house of twenty rooms.[21]

Descendants

Queen Heo and Suro had 12 children and the eldest son was Geodeung.

She requested Suro to let two of the children bear her maiden surname. Legendary genealogical records trace the origins of the Gimhae Heo to these two children.[5] The Gimhae Kims trace their origin to the other eight sons, and so does the Yi clan of Incheon.

According to the Jilburam, the remaining sons are said to have followed in their maternal uncle Po-ok's footsteps and devoted themselves to Buddhist meditation. They were named Hyejin, Gakcho, Jigam, Deonggyeon, Dumu, Jeongheong and Gyejang.[19] Overall, more than six million Koreans trace their lineage to Queen Heo.[6]

The remaining two children were daughters who were married respectively to a son of Talhae and a noble from Silla.

Kim Yoon-ok, wife of former South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, stated that she traces her ancestry to the royal family.[22][23]

Remains at Gimhae tomb

The tombs believed to be that of Heo Hwang-ok and Suro are located in Gimhae, South Korea. A pagoda traditionally held to have been brought to Korea on her ship is located near her grave. The Samguk Yusa reports that the pagoda was erected on her ship in order to calm the god of the ocean and allow the ship to pass. The unusual and rough form of this pagoda, unlike any other in Korea, may lend some credence to the account.[9]

A passage in the Samguk Yusa indicates that King Jilji built a Buddhist temple for the ancestral Queen Heo on the spot where she and King Suro were married.[24] He called the temple Wanghusa ("the Queen's temple") and provided it with ten gyeol of stipend land.[24] A gyeol or kyŏl (결 or 結), varied in size from 2.2 acres to 9 acres (8,903–36,422 m2) depending upon the fertility of the land.[25] The Samguk Yusa also records that the temple was built in 452. Since there is no other record of Buddhism having been adopted in 5th-century Gaya, modern scholars have interpreted this as an ancestral shrine rather than a Buddhist temple.[9]

Memorial in Ayodhya

In 2001, a Memorial of Heo Hwang-ok was inaugurated by a Korean delegation, which included over a hundred historians and government representatives.[26] In 2016, a Korean delegation proposed to develop the memorial. The proposal was accepted by then-Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Akhilesh Yadav.[27] On November 6, 2018, on the eve of Diwali celebration, South Korea's First Lady Kim Jung-sook, laid the foundation stone for the expansion and beautification of the existing memorial.[28][29] She offered tribute at the Queen Heo Memorial, attended a ceremony for the upgrade and beautification of the memorial and attended an elaborate Diwali celebration at Ayodhya along with the present Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, that included cultural shows and lighting of 300,000+ lights on the banks of Sarayu River.[30]

Reportedly, hundreds of South Koreans visit Ayodhya every year to pay homage to their legendary Queen Heo Hwang-ok.[31]

Controversy surrounding her existence

Indian accounts

Despite her connections to the two countries, there are no historical texts or official records in India that indicate an Indian princess traveling to Korea at the time including the country under the name Ayuta, her supposed country of birth. This ultimately makes her entire existence become solely dependent on the accounts made in Korea.

However, many Indian historians emphasize on Heo Hwang-ok's legacy that links India to Korea today rather than validating her actual existence in history.

Korean accounts

Heo Hwang-ok's rather unique background had been a subject of much discussion in South Korea among many historians. Despite her legendary status, many historians reject the idea that Queen Heo truly existed and have debunked her travel routes several times throughout history.

The first criticism stems from the fact that her existence is solely based on the accounts made in Samguk Yusa, a book that is widely regarded to be mostly fictional. Other older and more credible sources such as Samguk Sagi lack mentions about an Indian princess arriving in Gaya and marrying the king. It is believed that the writer of Samguk Yusa, Il-yeon exaggerated much of the claims to create a sense of familiarity towards Buddhism being a Buddhist monk himself.[32] Others also pointed out that due to the lack of technology to properly reach the Korean peninsula from ancient India at the time, her arrival would have been nearly impossible or at least, extremely difficult.[32]

Others have also pointed out the reason behind her supposed journey to the Korean kingdom being too vague. Many historians agree that the influence of India and Buddhism was profound for ancient Korean kingdoms at the time as many of them treated artifacts originating from India to be sacred.[33] However, historians have also pointed out that the agency of an Indian princess coming to Korea across the sea on a boat was very peculiar as ancient Korea was less known to India than countries such as ancient China.[32] Professor Ki-hwan Lee suggested that the story of Heo Hwang-ok was dramatized to elevate Gaya's stature of the Buddhist scene among the Korean kingdoms and to associate the sacred artifacts they possessed to something closer to that of the Indian culture.[33]

One of the biggest criticism stems from the book Garakguk-gi itself. Being written during the Goryeo Dynasty (the same period of Samguk Yusa's publication),[34] the book claims multiple accounts that revolves around events that happened almost a millennium before the foundation of the Goryeo kingdom. Many historians state that since Samguk Yusa and Garakguk-gi are both second hand accounts written in the same time period, the cross referencing needs to be carefully examined and researchers must remain skeptical.[34]

The consensus is that the existence of an Indian princess was very unlikely and that much of the stories found in Samguk Yusa were fabricated for political and religious reasons in Gaya at the time.[37] The same book claims that King Suro lived up to 157 years old and transformed into an eagle and a hawk to fight off his rivals according to the supposed Garakguk-gi, making her story even less credible stemming from the same source material.[37] However, in recent times, some have claimed that Queen Heo truly existed not as a foreign Indian, but as a native Korean.[38] This claim suggests that Garakgukgi (and in turn Samguk Yusa) alludes to the deification of King Suro by exaggerating much of his accomplishments to that of the supernatural.[37] According to the theory, King Suro's alleged age of death, his ability to transform into animals, his marriage to an Indian royalty and having 12 children are all based on probable facts that were greatly exaggerated to create a sense of superiority over the rulers of Gaya confederacy and the other Korean kingdoms.[38] Many believe his age of 157 years emphasizes on his longevity, his ability to transform into animals on his prowess, marriage to an Indian royalty on his religious affinity and the number of offspring (all happened to be sons) on his fertility, factors that were important to a reigning monarch at the time.[38] For further context, the only King to be officially recognized as the longest reigning monarch of Korea was King Jangsu (literal translation of "Long Life King") who lived up to the age of 97,[39] making King Suro's supposed age of death (and his other claims) even more questionable.[37] Following this theory, it can be deduced that Queen Heo's Korean ethnicity was elevated to that of the Indian heritage to create a sense of uniqueness[38] since marrying a royal princess from India, the birthplace of Buddha and Buddhism would be considered as a major accomplishment for the king of a Buddhist nation.[33]

Recent excavations led by Professor Byung-mo Kim at Hanyang University in 2018 discovered that the evidence which allegedly proved the existence of Queen Heo such as the famous relic resembling a pair of fish that was carved onto the tomb's gate, originated from Babylon rather than Ayuta,[40] further discrediting the possibilities of the queen being more than just a religious symbol. He added that despite much efforts to find any substantial evidence that linked the relics to Queen Heo's possible existence, the sheer commonness of the relics being found across all of Asia (starting from present day Iraq to the Japanese archipelago), he concluded that the relics did not originate from ancient India, but rather the aforementioned ancient Babylon.[40] Professor Kim added that engraving a depiction of a pair of fish was an ancient ritual stemming from a Babylonian belief that was thought to have brought eternal longevity and marital happiness to the individuals who were blessed.

Despite the historic inaccuracies surrounding her existence, many Korean historians stated that her iconic image as a legendary figure should persist as a means for the two countries to remain on good terms.[41]

In popular culture

- Portrayed by Seo Ji-hye in the 2010 MBC TV series Kim Su-ro, The Iron King.

- In February 2019, India and Korea signed an agreement on releasing a joint stamp, commemorating Queen Heo Hwang-ok.[42]

- Indian Council for Cultural Relations is releasing book that includes contact between foreign cultures and India, which mentions the story of Queen Heo Hwang-ok.[43]

See also

References

- Married Seok Gu-gwang (석구광).

- "The Indian princess who became a South Korean queen". BBC News. 4 November 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "The Indian princess who became a South Korean queen". BBC News. 4 November 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Legacy of Queen Suriratn, The Korea Times, 16 April 2017.

- Won Moo Hurh (2011). "I Will Shoot Them from My Loving Heart": Memoir of a South Korean Officer in the Korean War. McFarland. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-7864-8798-1.

- "Korean memorial to Indian princess". BBC News. 3 May 2001.

- "The Indian princess who became a South Korean queen". BBC News. 4 November 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Krishnan, Revathi (4 August 2020). "Ayodhya has 'important relations' with South Korea". ThePrint. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Kwon Ju-hyeon (권주현) (2003). 가야인의 삶과 문화 (Gayain-ui salm-gwa munhwa, The culture and life of the Gaya people). Seoul: Hyean. pp. 212–214. ISBN 89-8494-221-9.

- PTI, PTI (4 April 2020). "Work on Queen Heo Memorial in Ayodhya". TheWeek. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Il-yeon (tr. by Ha Tae-Hung & Grafton K. Mintz) (1972). Samguk Yusa. Seoul: Yonsei University Press. ISBN 89-7141-017-5.

- Choong Soon Kim (2011). Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea. AltaMira. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7591-2037-2.

- Robert E. Buswell (1991). Tracing Back the Radiance: Chinul's Korean Way of Zen. University of Hawaii Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8248-1427-4.

- Skand R. Tayal (2015). India and the Republic of Korea: Engaged Democracies. Taylor & Francis. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-317-34156-7.

Historians, however, believe that the Princess of Ayodhya is only a myth.

- Hyŏphoe, Han'guk Kwan'gwang (1968). Beautiful Korea. Huimang Publishing Company. p. 619.

Aboard the ship were Princess Ho Hwang-Ok of Ayut'a in the south of India.

- "Princess Suriratna of India marries King Suro of the Gaya Kingdom nearly 2,000 years ago". The Korea Post (in Korean). 8 September 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "The Legend of Princess Sriratna | Official website of Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Government of India". www.iccr.gov.in. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- No. 2039《三國遺事》CBETA 電子佛典 V1.21 普及版 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Taisho Tripitaka Vol. 49, CBETA Chinese Electronic Tripitaka V1.21, Normalized Version, T49n2039_p0983b14(07)

- Kim Choong Soon, 2011, Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea, AltairaPress, USA, Page 30-35.

- James Huntley Grayson (2001). Myths and Legends from Korea: An Annotated Compendium of Ancient and Modern Materials. Psychology Press. pp. 110–116. ISBN 978-0-7007-1241-0.

- Choong Soon Kim (16 October 2011). Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea. AltaMira Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-0-7591-2037-2.

- Lee, Tae-hoon (25 January 2010). "India Is First Lady Kims Ancestral Home". The Korea Times. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- "Lamp of the east". Deccan Herald. 13 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- Ilyeon, 1972, Samguk Yusa, tr. by Ha, Tae-Hung and Mintz, Grafton K., Yonsei University Press, Seoul, ISBN 89-7141-017-5, p. 168.

- Palais, James B. (1996), Confucian Statecraft & Korean Institutions: Yu Hyŏngwŏn and the Late Chosŏn Dynasty, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 9780295805115, p. 363

- "Korean memorial to Indian princess". BBC News. 6 March 2001.

- UP CM announces grand memorial of Queen Huh Wang-Ock, 1 March 2016, WebIndia123

- "UP's Faizabad district to be known as Ayodhya, says Yogi Adityanath". 6 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "Site for Heo Hwang-ok memorial in Ayodhya finalised". 2 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- South Korean first lady Kim Jung-sook celebrates Diwali in Ayodhya, revives links of Queen Heo Archived 23 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Hindustan Times, 10 July 2018

- "This is why hundreds of South Koreans visit Ayodhya every year". The Indian Express. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- "'허왕후 설화'는 어떻게 실제 역사로 둔갑했나". 뉴스톱 (in Korean). 10 September 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 수정: 2019.12.19 09:23, 입력: 2019 12 17 06:00 (17 December 2019). "[이기환의 흔적의 역사] "한반도엔 없는 돌"…가락국 허황후 '파사석탑의 정체'". www.khan.co.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Lee, Yang-jae (9 August 2022). "가야국의 실체와 『가락국기』". Tongilnews (in Korean). Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "1세대 고고학자 김병모 교수 퇴임 "한민족 원형찾기 나에겐 숙명"". 경향신문 (in Korean). 26 May 2006.

- Kim, Pyŏng-mo; 金秉模 (1994). Kim Suro Wangbi Hŏ Hwang-ok : ssangŏ ŭi pimil (Ch'op'an ed.). Sŏul T'ŭkpyŏlsi. ISBN 89-7365-035-1. OCLC 35714911.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 임동근 (11 August 2017). "[연합이매진] 인도 공주 허황옥이 가야에 온 까닭은". 연합뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "Queen Heo Hwang-ok". Namu (in Korean).

- Kim, Hung-gyu (March 2012). "Defenders and Conquerors: The Rhetoric of Royal Power in Korean Inscriptions from the Fifth to Seventh Centuries" (PDF). Cross-Currents: 1.

- Kim, Pyŏng-mo; 김병모 (2018). Hŏ Hwang-ok Rut'ŭ Indo esŏ Kaya kkaji : kogohakcha Kim Pyŏng-mo ŭi yŏksa ch'ujŏk sirijŭ. Pyŏng-mo Kim, 김병모 (Ch'op'an ed.). Sŏul-si: Yŏksa ŭi Ach'im. ISBN 978-89-93119-00-8. OCLC 302289415.

- "[김성회의 재미있는 다문화이야기] 이주민 '허황옥'과 '처용설화'는 사실일까?". 에듀인뉴스(EduinNews) (in Korean). 5 May 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- India, South Korea sign 6 pacts; to step-up cooperation in infrastructure, combating global crime. The Economic Times. 22 February 2019

- Ahuja, Sanjeev K (20 November 2020). "Korean Queen Huh Hwang-ok story to appear in ICCR's book on International love stories". Asian Community News. Retrieved 23 November 2020.