Quotient space (topology)

In topology and related areas of mathematics, the quotient space of a topological space under a given equivalence relation is a new topological space constructed by endowing the quotient set of the original topological space with the quotient topology, that is, with the finest topology that makes continuous the canonical projection map (the function that maps points to their equivalence classes). In other words, a subset of a quotient space is open if and only if its preimage under the canonical projection map is open in the original topological space.

Intuitively speaking, the points of each equivalence class are identified or "glued together" for forming a new topological space. For example, identifying the points of a sphere that belong to the same diameter produces the projective plane as a quotient space.

Definition

Let be a topological space, and let be an equivalence relation on The quotient set is the set of equivalence classes of elements of The equivalence class of is denoted

The construction of defines a canonical surjection As discussed below, is a quotient mapping, commonly called the canonical quotient map, or canonical projection map, associated to

The quotient space under is the set equipped with the quotient topology, whose open sets are those subsets whose preimage is open. In other words, is open in the quotient topology on if and only if is open in Similarly, a subset is closed if and only if is closed in

The quotient topology is the final topology on the quotient set, with respect to the map

Quotient map

A map is a quotient map (sometimes called an identification map[1]) if it is surjective and is equipped with the final topology induced by The latter condition admits two more-elementary phrasings: a subset is open (closed) if and only if is open (resp. closed). Every quotient map is continuous but not every continuous map is a quotient map.

Saturated sets

A subset of is called saturated (with respect to ) if it is of the form for some set which is true if and only if The assignment establishes a one-to-one correspondence (whose inverse is ) between subsets of and saturated subsets of With this terminology, a surjection is a quotient map if and only if for every saturated subset of is open in if and only if is open in In particular, open subsets of that are not saturated have no impact on whether the function is a quotient map (or, indeed, continuous: a function is continuous if and only if, for every saturated such that is open in , the set is open in ).

Indeed, if is a topology on and is any map then set of all that are saturated subsets of forms a topology on If is also a topological space then is a quotient map (respectively, continuous) if and only if the same is true of

Quotient space of fibers characterization

Given an equivalence relation on denote the equivalence class of a point by and let denote the set of equivalence classes. The map that sends points to their equivalence classes (that is, it is defined by for every ) is called the canonical map. It is a surjective map and for all if and only if consequently, for all In particular, this shows that the set of equivalence class is exactly the set of fibers of the canonical map If is a topological space then giving the quotient topology induced by will make it into a quotient space and make into a quotient map. Up to a homeomorphism, this construction is representative of all quotient spaces; the precise meaning of this is now explained.

Let be a surjection between topological spaces (not yet assumed to be continuous or a quotient map) and declare for all that if and only if Then is an equivalence relation on such that for every which implies that (defined by ) is a singleton set; denote the unique element in by (so by definition, ). The assignment defines a bijection between the fibers of and points in

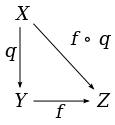

Define the map as above (by ) and give the quotient topology induced by (which makes a quotient map). These maps are related by:

From this and the fact that is a quotient map, it follows that is continuous if and only if this is true of Furthermore, is a quotient map if and only if is a homeomorphism (or equivalently, if and only if both and its inverse are continuous).

Related definitions

A hereditarily quotient map is a surjective map with the property that for every subset the restriction is also a quotient map. There exist quotient maps that are not hereditarily quotient.

Examples

- Gluing. Topologists talk of gluing points together. If is a topological space, gluing the points and in means considering the quotient space obtained from the equivalence relation if and only if or (or ).

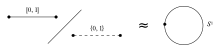

- Consider the unit square and the equivalence relation ~ generated by the requirement that all boundary points be equivalent, thus identifying all boundary points to a single equivalence class. Then is homeomorphic to the sphere

- Adjunction space. More generally, suppose is a space and is a subspace of One can identify all points in to a single equivalence class and leave points outside of equivalent only to themselves. The resulting quotient space is denoted The 2-sphere is then homeomorphic to a closed disc with its boundary identified to a single point:

- Consider the set of real numbers with the ordinary topology, and write if and only if is an integer. Then the quotient space is homeomorphic to the unit circle via the homeomorphism which sends the equivalence class of to

- A generalization of the previous example is the following: Suppose a topological group acts continuously on a space One can form an equivalence relation on by saying points are equivalent if and only if they lie in the same orbit. The quotient space under this relation is called the orbit space, denoted In the previous example acts on by translation. The orbit space is homeomorphic to

- Note: The notation is somewhat ambiguous. If is understood to be a group acting on via addition, then the quotient is the circle. However, if is thought of as a topological subspace of (that is identified as a single point) then the quotient (which is identifiable with the set ) is a countably infinite bouquet of circles joined at a single point

- This next example shows that it is in general not true that if is a quotient map then every convergent sequence (respectively, every convergent net) in has a lift (by ) to a convergent sequence (or convergent net) in Let and Let and let be the quotient map so that and for every The map defined by is well-defined (because ) and a homeomorphism. Let and let be any sequences (or more generally, any nets) valued in such that in Then the sequence converges to in but there does not exist any convergent lift of this sequence by the quotient map (that is, there is no sequence in that both converges to some and satisfies for every ). This counterexample can be generalized to nets by letting be any directed set, and making into a net by declaring that for any holds if and only if both (1) and (2) if then the -indexed net defined by letting equal and equal to has no lift (by ) to a convergent -indexed net in

Properties

Quotient maps are characterized among surjective maps by the following property: if is any topological space and is any function, then is continuous if and only if is continuous.

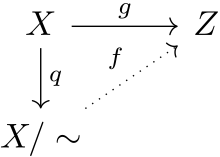

The quotient space together with the quotient map is characterized by the following universal property: if is a continuous map such that implies for all then there exists a unique continuous map such that In other words, the following diagram commutes:

One says that descends to the quotient for expressing this, that is that it factorizes through the quotient space. The continuous maps defined on are, therefore, precisely those maps which arise from continuous maps defined on that respect the equivalence relation (in the sense that they send equivalent elements to the same image). This criterion is copiously used when studying quotient spaces.

Given a continuous surjection it is useful to have criteria by which one can determine if is a quotient map. Two sufficient criteria are that be open or closed. Note that these conditions are only sufficient, not necessary. It is easy to construct examples of quotient maps that are neither open nor closed. For topological groups, the quotient map is open.

Compatibility with other topological notions

- In general, quotient spaces are ill-behaved with respect to separation axioms. The separation properties of need not be inherited by and may have separation properties not shared by

- is a T1 space if and only if every equivalence class of is closed in

- If the quotient map is open, then is a Hausdorff space if and only if ~ is a closed subset of the product space

- If a space is connected or path connected, then so are all its quotient spaces.

- A quotient space of a simply connected or contractible space need not share those properties.

- If a space is compact, then so are all its quotient spaces.

- A quotient space of a locally compact space need not be locally compact.

- The topological dimension of a quotient space can be more (as well as less) than the dimension of the original space; space-filling curves provide such examples.

See also

Topology

- Covering space – Type of continuous map in topology

- Disjoint union (topology) – space formed by equipping the disjoint union of the underlying sets with a natural topology called the disjoint union topology

- Final topology – Finest topology making some functions continuous

- Mapping cone (topology) – topological construction

- Product space – Topology on Cartesian products of topological spaces

- Subspace (topology) – Inherited topology

- Topological space – Mathematical space with a notion of closeness

Algebra

- Quotient category

- Quotient group – Group obtained by aggregating similar elements of a larger group

- Quotient space (linear algebra) – Vector space consisting of affine subsets

- Mapping cone (homological algebra) – Tool in homological algebra

References

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1989) [1966]. General Topology: Chapters 1–4 [Topologie Générale]. Éléments de mathématique. Berlin New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-64241-1. OCLC 18588129.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1989) [1967]. General Topology 2: Chapters 5–10 [Topologie Générale]. Éléments de mathématique. Vol. 4. Berlin New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-64563-4. OCLC 246032063.

- Brown, Ronald (2006), Topology and Groupoids, Booksurge, ISBN 1-4196-2722-8

- Dixmier, Jacques (1984). General Topology. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Translated by Berberian, S. K. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90972-1. OCLC 10277303.

- Dugundji, James (1966). Topology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-697-06889-7. OCLC 395340485.

- Kelley, John L. (1975). General Topology. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 27. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-90125-1. OCLC 338047.

- Munkres, James R. (2000). Topology (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. ISBN 978-0-13-181629-9. OCLC 42683260.

- Willard, Stephen (2004) [1970]. General Topology. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43479-7. OCLC 115240.

- Willard, Stephen (1970). General Topology. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-486-43479-6.