Hereford Mappa Mundi

The Hereford Mappa Mundi is a medieval map of the known world (Latin: mappa mundi), of a form deriving from the T and O pattern, dating from c. 1300. Archeological scholars believe the map to have originated from eastern England in either Yorkshire or Lincolnshire before it was transported westward to the Hereford Cathedral in Herefordshire where it has remained ever since.[1] It is displayed at Hereford Cathedral in Hereford, England.[2] It is the largest medieval map still known to exist. A larger mappa mundi, the Ebstorf map, was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943, though photographs of it survive.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi hung, with little regard, for many years on a wall of a choir aisle in the cathedral. During the troubled times of the Commonwealth the map had been laid beneath the floor of Bishop Audley's Chantry, where it remained secreted for some time. In 1855 it was cleaned and repaired at the British Museum. During the Second World War, for safety reasons, the mappa mundi and other valuable manuscripts from Hereford Cathedral Library were kept elsewhere and returned to the collection in 1946.[3]

In 1988, a financial crisis in the Diocese of Hereford caused the Dean and Chapter to propose selling the mappa mundi.[4] After much controversy, large donations from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Paul Getty and members of the public kept the map in Hereford and allowed the construction of a new library designed by Sir William Whitfield to house the map and the chained libraries of the Cathedral and of All Saints' Church. The new Library Building in the south east corner of the cathedral close opened in 1996.[3] An open-access high-resolution digital image of the map with more than 1,000 place and name annotations is included among the thirteen medieval maps of the world edited in the Virtual Mappa project. In 1991 British Rail Class 31 locomotive No.31405 was named "Mappa Mundi" at a ceremony at the Hereford Rail Day.

Christopher de Hamel, an expert on medieval manuscripts believes that the map's historical significance cannot be overstated: "... it is without parallel the most important and most celebrated medieval map in any form, the most remarkable illustrated English manuscript of any kind, and certainly the greatest extant thirteenth-century pictorial manuscript."[5] The map was created with the intent of its being appreciated as an intricate work of art rather than as a navigational tool.[1]

Features

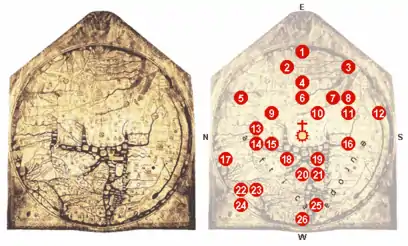

Drawn on a single sheet of vellum, it measures 158 cm by 133 cm,[2] some 52 in (130 cm) in diameter and is the largest medieval map known still to exist. The writing is in black ink, with additional red and gold, and blue or green for water (with the Red Sea (8) coloured red). It depicts 420 towns, 15 Biblical events, 33 animals and plants, 32 people, and five scenes from classical mythology.[2]

Utilizing the contemporary medieval styled T-O map of the time, the map is a biblically inspired map which shows Jerusalem drawn in the centre of the circle; east is on top, showing the Garden of Eden in a circle at the edge of the world (1).[6] Great Britain is drawn at the northwestern border (bottom left, 22 and 23). Curiously, the labels for Africa and Europe are reversed, with Europe scribed in red and gold as "Africa" and vice versa.[2] The Mediterranean Sea is shown at the bottom center, with the Straits of Gibraltar marking its most western point.[6]

Various animals not well known to Europeans at the time, such as elephants and camels, are depicted on the map. Elephants were shown to be very practical beasts of war, as they were strong enough to transport siege equipment across great distances, as well as being capable of supporting platforms from which rows of archers were able to stand and fire, or so envisioned the medieval English cartographers. Mythical beasts such as the legendary monoceros are also depicted on the map. The map also features a number of monsters and inhuman races. One such race is the Blemmyes, a headless tribe whose facial features were situated on their chests.[7]

The map is based on traditional accounts and earlier maps such as the one of the Beatus of Liébana codex, and is very similar to the Ebstorf Map, the Psalter world map, and the Sawley map (erroneously for considerable time called the Henry of Mainz map); it does not correspond to the geographical knowledge of the 14th century. Note, for example, that the Caspian Sea (5) connects to the encircling ocean (upper left). This is in spite of William of Rubruck's having reported it to be landlocked in 1255, several decades before the map's creation; see also Portolan chart.

The "T and O" shape does not imply that its creators believed in a flat Earth. The spherical shape of the Earth was already known to the ancient Greeks and Romans and the idea was never entirely forgotten even in the Middle Ages, and thus the circular representation may well be considered a conventional attempt at a projection: in spite of the acceptance of a spherical Earth, only the known parts of the Northern Hemisphere were believed to be inhabitable by human beings (see antipodes), so that the circular representation remained adequate. The long river on the far right is the River Nile (12), and the T shape is established by the Mediterranean Sea (19-21-25) and the rivers Don (13) and Nile (16).

It is the earliest known map to depict the mythical St Brendan's Isle,[8] which then appeared on many other maps. including Martin Behaim's Erdapfel of 1492.

Authorship

The map is signed by or attributed to one "Richard of Haldingham and Lafford", also known as Richard de Bello, "prebend of Lafford in Lincoln Cathedral". However, this attribution isn't completely agreed upon, it being suggested that the exquisite level of detail included in the map could not have been completed by one person. Some people believe that the map was originally created by Richard of Haldingham and Lafford and that at his death it passed to his younger cousin, Richard de Bello. Once it was in de Bello's possession, de Bello and his patron Richard Swindfield worked on the map.[9]

It was long believed that the mappa mundi was created, not in Hereford, but in Lincoln because the city of Lincoln was drawn in considerable detail and was represented by a cathedral (accurately) located on a hill near a river.[10] Hereford, on the other hand, was represented only by a cathedral, a seeming afterthought drawn by a different hand when compared with other features of the map.[11] However, recent research on the origin of the wood in the frame suggests it may in fact have been created in or around Hereford.[12]

Locations

0 – At the centre of the map: Jerusalem, above it: the crucifix.

1 – Paradise, surrounded by a wall and a ring of fire. During World War II this was printed in Japanese textbooks since Paradise appears to be roughly in the location of Japan.[13]

2 – The Ganges and its delta.

3 – The fabulous island of Taphana, sometimes interpreted as Sri Lanka or Sumatra.

4 – Rivers Indus and Tigris.

5 – The Caspian Sea, and the land of Gog and Magog

6 – Babylon and the Euphrates.

7 – The Persian Gulf.

8 – The Red Sea (painted in red).

9 – Noah's Ark.

10 – The Dead Sea, Sodom and Gomorrah, with the River Jordan, coming from the Sea of Galilee; above: Lot's wife.

11 – Egypt with the River Nile.

12 – The River Nile (?), or possibly an allusion to the equatorial ocean; far outside: a land of the monstrous races, possibly the Antipodes.

13 – The Azov Sea with rivers Don and Dnieper; above: the Golden Fleece.

14 – Constantinople; left of it the Danube's delta.

15 – The Aegean Sea.

16 – Oversized delta of the Nile with Alexandria's Pharos lighthouse.

17 – The legendary Norwegian Gansmir, with his skis and ski pole.

18 – Greece with Mount Olympus, Athens and Corinth

19 – Misplaced Crete with the Minotaur's circular labyrinth.

20 – The Adriatic Sea; Italy with Rome, honoured by a popular Latin hexameter; Roma caput mundi tenet orbis frena rotundi ("Rome, the head of the world, holds the reins of the round globe").

21 – Sicily and Carthage, opposing Rome, right of it.

22 – Scotland.

23 – England.

24 – Ireland.

25 – The Balearic Islands.

26 – The Strait of Gibraltar (the Pillars of Hercules).

See also

References

- "Hereford Mappa Mundi". Atlas Obscura.

- Edson, Evelyn (1997) Mapping Time and Space: How Medieval Mapmakers Viewed Their World, The British Library

- Alington, Gabriel (2000). The Hereford Mappa Mundi: Journey to Hereford. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Cromwell Press.

- Driver, Christopher (19 November 1988). "World time forgot: the 13th-century world map up for sale is not the only neglected treasure of Hereford Cathedral". The Guardian.

- "Discover the Last Chained Libraries in England". Europe Up Close. 19 November 2019.

- Brown, Kevin J. Maps Through the Ages. White Star Publishers. p. 20.

- Wellesley, Mary (21 April 2022). "In Hereford". London Review of Books. 44 (8).

- Magasich-Airola, Jorge; de Beer, Jean-Marc (July 2007). America magica : when Renaissance Europe thought it had conquered paradise (2nd ed.). Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1843312925.

- Brotton, Jerry (2014). Great Maps: The World's Masterpieces Explored and Explained. New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1465424631.

- "The Hereford Mappa Mundi". Historic UK.

- Harvey, P. D. A. (1996). Mappa Mundi: The Hereford World Map. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- "Cathedral lays claim to medieval map". BBC News. 28 May 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 綾部 宗彦 「知られざる古代日本キリスト伝説」 ISBN 4054035817. p. 186

Further reading

A series of close-up photographs of the entire map, along with annotated transcriptions and English translations of all the text thereon, have been published in Scott D. Westrem, The Hereford Map, Terrarum Orbis 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001) ISBN 2-503-51056-6.

An extensive early study was undertaken by W. L. Bevan and H. W. Phillott: Medieval Geography: An Essay in Illustration of the Hereford Mappa Mundi (London: Stanford, 1873). online

See also Debra Higgs Strickland, "Edward I, Exodus, and England on the Hereford World Map", Speculum 93.2 (2018): 420–69.

External links

- "Explore the Hereford Mappa Mundi" at the official dedicated website launched in 2014

- "The Mappa Mundi" at the Hereford Cathedral site

- "The Hereford Mappamundi" by J. Siebold Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Peter Frankopan: Art Detective Podcast, 22 Mar 2017

- Digital Facsimile edition: Virtual Mappa: Digital Editions of Early Medieval Maps of the World, eds. Martin Foys, Heather Wacha, et al. (Philadelphia, PA: Schoenberg Institute of Manuscript Studies, 2020). DOI: 10.21231/ef21-ev82.

- The Mapping Mandeville Digital Project, ed. John Wyatt Greenlee, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville plotted onto the Hereford Mappa Mundi